BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Congressional Republicans are floating a proposal that would cut Social Security Disability Insurance (DI) benefits for some beneficiaries who work — which would hurt up to a half-million of the most vulnerable Americans, discourage work for many such beneficiaries, and boost DI payment errors.

Currently, workers with severe medical impairments who qualify for DI are encouraged to return to work — but they can lose their entire benefit if they earn more than $1,090 per month for a sustained period. Now, some lawmakers want to replace that “cash cliff” with a “benefit offset,” under which DI benefits would gradually fall as earnings rise. Proponents describe it as a way to spur more work. But it’s not that simple, as we explain in a new paper.

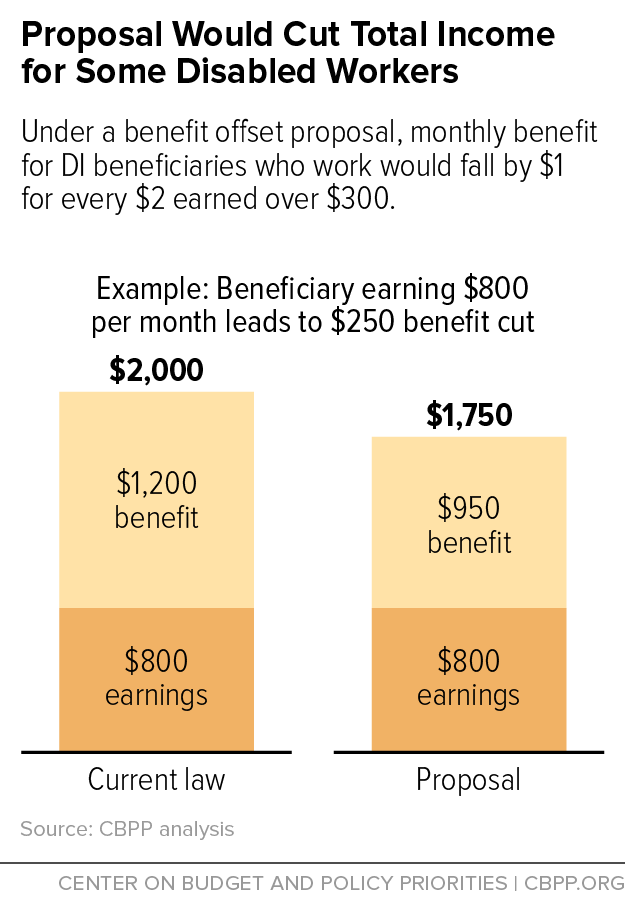

In particular, congressional Republicans have floated a benefit offset that would begin to phase down benefits when earnings reach only about $300 a month — well below the current limit. Beneficiaries earning between $300 and $1,090 a month would face benefit cuts, while those earning above $1,090 (the current amount known as DI’s substantial gainful activity, or SGA, threshold) would be newly eligible for a small benefit.

An offset starting as low as $300 could backfire. Here are four reasons why:

- It would discourage work for many beneficiaries. Beneficiaries who earn between $300 and $1,090 would lose 50 cents of their benefits for each dollar of earnings in that range. The chart below shows how an offset could cut the benefits — and income — of a disabled worker with a typical benefit of about $1,200. An earnings penalty like this would likely lead some beneficiaries to work less, not more.

-

It would harm many vulnerable beneficiaries. Under an offset starting at $300, beneficiaries who earn more than SGA would be better off, while those who earn between $300 and SGA would be worse off. About 500,000 DI beneficiaries earned between $3,600 (that is, an average of $300 a month) and annualized SGA in 2013.

-

It could increase payment errors. DI has a high payment accuracy rate of nearly 99 percent. Beneficiaries’ earnings are a major cause of the overpayments that do occur, whether because beneficiaries fail to report their earnings promptly or the Social Security Administration falls behind on earnings reports. Overpayments would increase if the earnings threshold dropped, affecting more workers’ benefits. Recovering those overpayments may require reducing or withholding benefits months later, when the worker’s job may have ended and he or she badly needs the money for living expenses.

-

Beneficiaries could have significant earnings and still collect disability benefits. A beneficiary who qualifies for an above-average benefit of $1,500 could earn up to $3,000 a month — or $36,000 a year — and still get a $150 monthly benefit, after the offset. Although this wouldn’t happen often, it may be difficult to justify paying disability benefits to people with earnings at those levels.

Substituting a gradual benefit reduction for the cash cliff poses tough tradeoffs, and only a carefully designed demonstration project can determine whether a particular benefit offset has desirable effects overall. Policymakers who are serious about evidence-based policymaking shouldn’t enact a $1-for-$2 offset before it’s rigorously tested and evaluated.

Click here to read our full paper on benefit offset proposals.