Congress is considering whether to replace the “cash cliff” for Social Security Disability Insurance (DI), under which beneficiaries lose their entire benefit if they earn more than $1,090 a month for a sustained period, with a “benefit offset,” under which DI benefits would gradually decline as earnings rise. Proponents of such a change often describe it as a way to reduce work disincentives and spur more work. Eliminating the cash cliff and substituting a gradual benefit reduction is unlikely to have a big payoff, however, and poses difficult tradeoffs. If the reduction cuts into current-law benefits, it could result in a net decrease in work, harm vulnerable beneficiaries, and increase DI overpayment rates.

Only a carefully designed demonstration project can determine whether a particular benefit offset has desirable effects overall. For this reason, policymakers should not rush to enact an untested benefit offset that could affect hundreds of thousands of workers with disabilities in coming decades without rigorously testing various approaches to a benefit offset. Expectations should be realistic, however, and grounded in experience. Numerous past demonstration projects, and the characteristics of DI beneficiaries, should lead us to expect only limited results.

Under current law, DI beneficiaries can earn up to Social Security’s substantial gainful activity threshold (SGA), set at $1,090 per month in 2015, without having their benefits suspended.[1] Beneficiaries may earn unlimited amounts during a nine-month trial work period and three-month grace period, but if they continue to earn more than the SGA level after that, the law suspends their entire benefit.[2] After completing the trial work period and grace period, suspended beneficiaries may — for the next three years — return to the DI rolls automatically if their monthly earnings sink below $1,090. If their benefits are formally terminated at the end of that period, they generally remain eligible for expedited reinstatement for the next five years, without serving another five-month waiting period and with streamlined eligibility criteria, if their earnings fall below SGA and their original disability persists.

The fact that beneficiaries lose their entire benefit for sustained earnings above SGA is known as the cash cliff, which some researchers, advocates for people with disabilities, and members of Congress have criticized for discouraging work. This has led some to propose certain policy changes (see “Eliminating the Cash Cliff,” below). There is little hard evidence, however, that the cash cliff keeps large numbers of beneficiaries from working to their full potential.

Despite understandable concerns about DI’s cash cliff, it appears to make only a small real-world difference. Eligibility for DI is strict, and the rules are designed to weed out beneficiaries who could support themselves through work. To qualify, applicants must have a severe, medically determinable impairment that has already lasted five months and is expected to last at least 12 months or result in death. Their impairment must make them unable to engage in substantial gainful activity at any work that exists in the national economy — regardless of whether such work is available where the applicant lives, whether a specific job vacancy exists, or whether he or she would be hired.[3] The Social Security Administration (SSA) rejects a majority of applicants, and even rejected applicants fare poorly in the labor market afterward. Barely half of older DI applicants who are rejected have any earnings two years after rejection, and among those who do, earnings tend to be low. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development notes that the eligibility criteria for DI benefits in the United States are among the most stringent of those in any country with an advanced economy.[4]

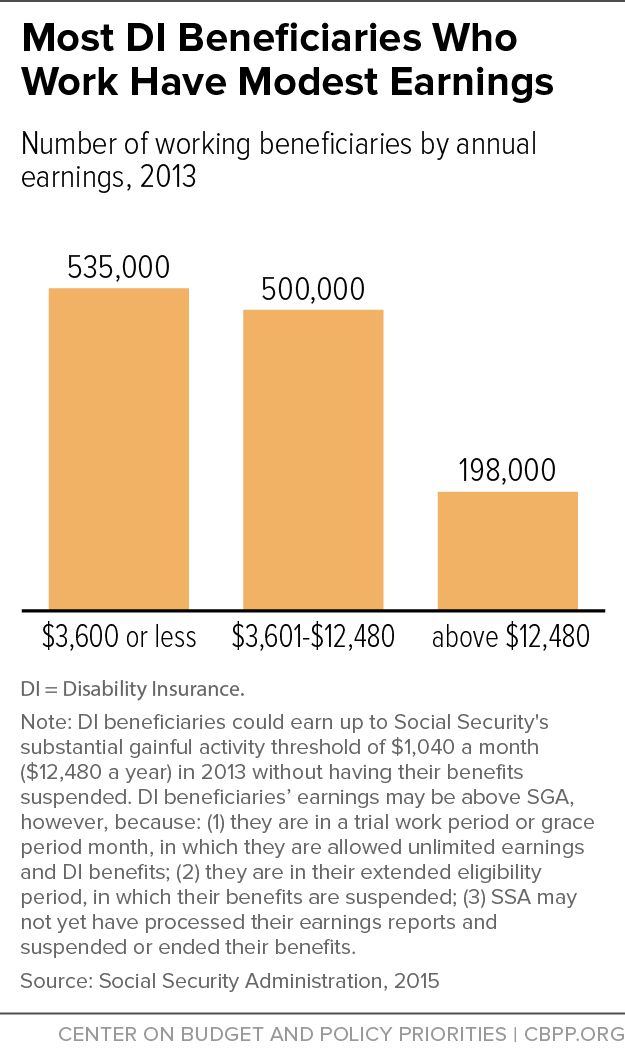

Given these criteria, it’s no surprise that most DI beneficiaries do not have significant earnings.[5] Research consistently finds that most beneficiaries have limited work capacity and face significant barriers to work.[6] They suffer from poor health and functional limitations, and their death rates are at least three times as high as the general population’s.[7] Many also face a lack of reliable transportation, inflexible work arrangements, inaccessible workplaces, or employment discrimination.

Even if they can surmount these obstacles, very few DI beneficiaries can earn enough to achieve self-sufficiency. Only a minority return to work. Of beneficiaries who were tracked during a ten-year period, roughly a quarter worked at some point after their DI application was approved, but generally episodically and at low earnings.[8] Just 4 percent earned enough to work their way off the DI rolls, and about one-quarter of them subsequently returned to the program. The most reasonable explanation is their severe impairments, rather than the lack of work incentives.

“Parking” is the nickname for the practice of holding earnings just below the level that would trigger the loss of Disability Insurance (DI) benefits — the substantial gainful activity (SGA) threshold, $1,090 a month in 2015.a “Parking” would seem to make economic sense for the relatively few DI beneficiaries who work. But the evidence indicates that it is rare:

- The Government Accountability Office (GAO) found in 2002 that, on average, about 7 percent of DI beneficiaries who worked between 1985 and 1997 — accounting for about 1 percent of DI beneficiaries overall — had earnings between 75 and 100 percent of SGA, where you would expect them to “park” if parking were widespread. And of that small group, GAO found that the earnings of most declined substantially over time. Only a few held their earnings consistently in that range. GAO noted limitations in the data but concluded that “most new DI beneficiaries were either not able or not inclined to increase their earnings or work at all.” A later GAO study of beneficiaries who completed vocational rehabilitation between 2000 and 2003 found similar results.b

- A study by researchers at Mathematica and the Social Security Administration (SSA) of people who had completed their trial work period concluded that only 0.2 to 0.4 percent of all DI beneficiaries “parked” in a typical month between 2002 and 2006.c

- A 2015 study by Mathematica and SSA researchers found that only 1.0 percent of all DI-only beneficiaries (or about 9 percent of DI-only beneficiaries who had earnings) made between $10,000 a year and the annualized SGA (then $12,000) in 2011, roughly the range where one would expect to find “parking.”d

- In a related vein, RAND researchers found that only about 1.6 percent of DI beneficiaries began to work when they were converted to Social Security old-age benefits and no longer faced earnings limits.e

In short, studies of “parking” or related behavior provide little evidence that DI beneficiaries have significant work capacity that changing the rules would unleash.

a SGA has varied historically. It was frozen at $300 for most of the 1980s; frozen at $500 for most of the 1990s; then raised and indexed since 1999. See http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/COLA/sga.html.

b Government Accountability Office, as summarized in “Disability Programs in the 21st Century: Substantial Gainful Activity,” Social Security Advisory Board, April 2009, http://www.ssab.gov/Portals/0/Documents/SGA-issue-brief.pdf

c Jody Schimmel, David C. Stapleton, and Jae G. Song, “How Common is "Parking" among Social Security Disability Insurance Beneficiaries? Evidence from the 1999 Change in the Earnings Level of Substantial Gainful Activity,” Social Security Bulletin, 2011, http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v71n4/v71n4p77.html.

d David R. Mann, Arif Mamun, and Jeffrey Hemmeter, “Employment, Earnings, and Primary Impairments Among Beneficiaries of Social Security Disability Programs,” Social Security Bulletin, 2015, http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v75n2/v75n2p19.html.

e Nicole Maestas and Na Yin, “The Labor Supply Effects of Disability Insurance Work Disincentives: Evidence from the Automatic Conversion to Retirement Benefits at Full Retirement Age,” Michigan Retirement Research Center, 2008, http://www.mrrc.isr.umich.edu/publications/papers/pdf/wp194.pdf.

For the small fraction of DI beneficiaries for whom financial incentives are a factor, economic analyses consistently find that DI’s effect on earnings is small. One widely cited study estimates that “marginal” beneficiaries — those who might plausibly have been denied (and are less severely impaired than the average beneficiary) — would earn only $3,800 to $4,600 more annually if they were not receiving DI benefits.[9] Studies of “parking” (deliberately holding earnings just below the maximum allowed) — and of beneficiaries who, once they are converted from DI benefits to retirement benefits upon reaching Social Security’s “full retirement age,” can earn unlimited amounts — demonstrate that few DI beneficiaries intentionally set their earnings just under the SGA threshold. (See Box 1.)

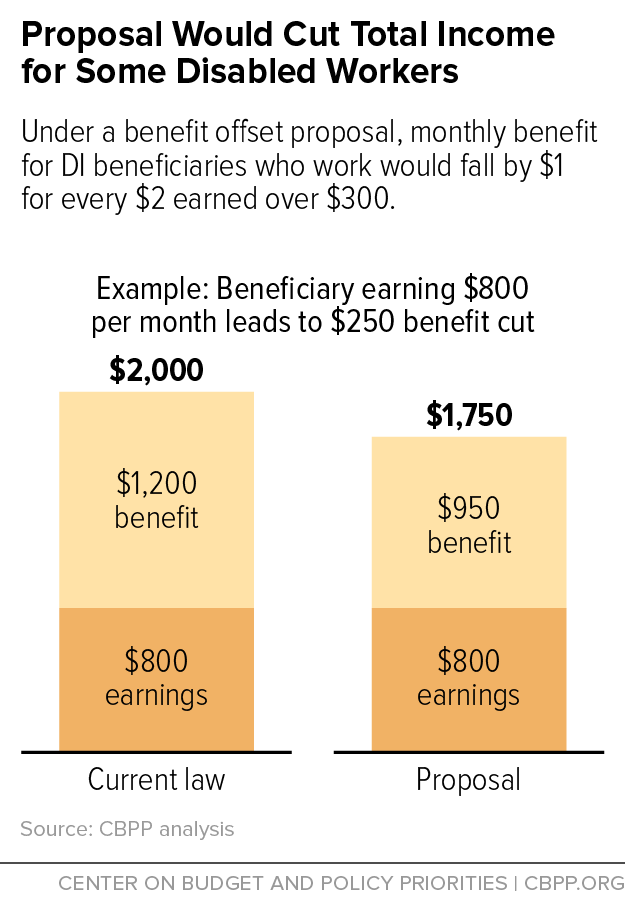

Alternatives to the cash cliff vary significantly. One approach now being discussed would eliminate DI’s cash cliff and instead reduce benefits gradually, by $1 for each $2 of earnings once earnings exceed a certain level.[10] For example, SSA is testing an offset that would reduce benefits by $1 for every $2 earned above the SGA threshold. Some congressional Republicans, meanwhile, have floated a $1-for-$2 benefit offset with a crucial difference: instead of starting at the SGA level of $1,090 in monthly earnings, benefits would begin to phase down when earnings reach roughly $300 per month.[11] Two expert panels have proposed a middle path, as discussed in Box 2.

Eliminating the cash cliff and substituting a gradual benefit reduction is unlikely to have a big payoff and poses difficult tradeoffs, depending on where the offset begins.

An offset starting at the SGA threshold would slightly encourage work and raise costs. A benefit offset that started at (rather than below) the SGA level would add to DI costs and, based on the available evidence, increase work only a small amount. Gradually reducing, rather than eliminating, benefits for workers who earn more than SGA for a sustained period would better reward work but produce only a small increase in earnings.

An offset starting below the SGA level would encourage work for some but discourage it for others and harm some vulnerable beneficiaries. An offset starting below SGA would limit costs but could have negative consequences. Such an offset would reward work among beneficiaries who can earn more than SGA. It would penalize work, however, among people with earnings between the new threshold and SGA. At the $1-for-$2 rate, it would offset earnings in that range by 50 percent: essentially, it would increase the marginal tax rate for many workers with disabilities by 50 percentage points. This would make work less attractive for them, while also reducing their income and pushing some of them into (or deeper into) poverty. As a result, it isn’t clear whether total work effort would increase or decrease under a benefit offset that starts well below the SGA. Such a change would essentially shift benefits from more severely impaired workers who are not able to earn more to less impaired workers who can.

Two respected organizations have recently weighed in on whether, and how, to replace the Disability Insurance (DI) cash cliff with a gradual benefit offset for working beneficiaries. The proposals give a sense of the many factors — adequacy, cost, simplicity, and others — that policymakers must weigh.

- The Social Security task force of the Consortium of Citizens with Disabilities (CCD) has proposed adopting an offset of $1 in DI benefits for each $2 of earnings over $780 per month.a (The CCD would also eliminate the trial work period, along with the extended period of eligibility, in favor of a permanent right to rejoin the DI program if former beneficiaries remain severely impaired and their earnings sink.) The CCD also advocates adjusting the “earned income exclusion” in Supplemental Security Income (SSI) — the threshold at which SSI benefits are reduced for earnings, which has been frozen since 1974 — for over four decades’ worth of inflation, a change that would improve the lot of many SSI beneficiaries with very modest earnings.

- The Disability Insurance Working Group at the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC) recommends setting the threshold for a $1-for-$2 offset at $700 or more for beneficiaries who receive both DI and SSI benefits (so-called concurrent beneficiaries, who make up about one-eighth of all DI beneficiaries).b For DI-only beneficiaries, BPC recommends testing and evaluating various thresholds for an offset. The BPC working group doesn’t make any recommendations for SSI-only beneficiaries, presumably because they fell outside the scope of the group’s mandate.

The CCD and BPC recommendations differ in details, but it’s notable that both mention thresholds well above the $300 or so that House Republicans are reportedly considering. The BPC expressed concern at such a stringent threshold: “A lower-cost benefit offset package for all beneficiaries would require the offset to begin at a threshold so low that the income security of current beneficiaries would be threatened.”

SSA is currently operating a Benefit Offset National Demonstration (BOND) to test an offset that starts at the SGA level and reduces benefits by $1 for every $2 earned above that threshold. Preliminary results show only a very modest increase in earnings, a slight increase in benefit costs, and no reduction in the number of beneficiaries. BOND consists of two stages, both of which will conclude in 2017:

- The first stage of BOND examines how a national benefit offset would affect the entire DI population. So far, researchers have found “no evidence that the benefit offset had an impact on earnings.” [12] However, DI benefit payments — and thus program costs — were slightly higher.

- The second stage of BOND focuses on beneficiaries most likely to respond to work incentives.[13] The sample includes only recruited and informed volunteers (about 5 percent of those invited to participate volunteered for the study) and excludes beneficiaries who also receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI).[14] For this subset of beneficiaries, the benefit offset increased average earnings in 2012 by a small amount, about $300 a year. Total DI benefit payments were also somewhat higher, because beneficiaries with sustained earnings above SGA received a partial benefit, rather than having their benefits suspended.

An earlier study, the Benefit Offset Four-State Pilot Demonstration (BOPD), tested a benefit offset solely on volunteers.[15] Those volunteers represented the roughly 20 percent of the DI population most interested in and able to work, according to evaluators. Among these beneficiaries, the benefit offset had no statistically significant effect on average earnings or on the percentage of beneficiaries who were employed. There was a 4 percentage-point increase in workers with earnings above SGA, along with a resultant increase in DI benefit payments.

Neither BOND nor its earlier pilot could test another possible source of added cost: so-called “induced filers.” A $1-for-$2 benefit offset may encourage more people to apply to the DI program if they view the combination of cash benefits plus earnings (and Medicare, after a two-year wait) as more appealing than their current job.

While there is preliminary evidence of slightly more work with a benefit offset that starts at the SGA, there is no evidence regarding the effects of a benefit offset that starts below the SGA. The $1-for-$2 benefit offset reportedly being discussed by House Republicans would begin to phase down benefits when earnings reach roughly $300 per month. An offset at this level reportedly would be cost neutral, neither adding to DI’s costs nor improving its solvency.[16] Beneficiaries earning between $300 and $1,090 a month would face benefit reductions, however, while those with earnings above $1,090 a month could become newly eligible for DI.

An offset starting at around $300 could have significant unintended consequences.

-

It would discourage work for many beneficiaries. Such an offset would penalize work for some beneficiaries by reducing their DI benefits by $1 for every $2 they earn between $300 and the SGA level, essentially increasing their marginal tax rate by 50 percentage points.

Consider the illustrative worker in Figure 1, for example, whose monthly earnings of $800 would lead to a $250 benefit cut and a one-eighth reduction in income. Such work disincentives would likely lead to a reduction in the amount that some beneficiaries work.

-

It would harm a number of vulnerable beneficiaries. An offset starting at $300 would create winners and losers among working beneficiaries. Beneficiaries who earn more than the SGA threshold would be better off, while beneficiaries who earn between $300 and the SGA would be worse off. In 2013, about 500,000 DI beneficiaries earned between $3,600 (which averages to $300 a month) and the annualized SGA level (see Figure 2).[17] Many are already working as much as they can to eke out a modest living from DI benefits plus part-time work, and the proposal would deal a blow to their standard of living.

-

It could increase payment errors. While DI’s payment accuracy rate is nearly 99 percent, beneficiaries’ failure to report their earnings in a timely manner, as well as delays by SSA in processing their reports, are a major cause of the overpayments that occur.[18] These overpayments would increase if the earnings threshold dropped, affecting more workers’ benefits; SSA already struggles to keep up with the earnings reports it receives. In addition, processing lags mean that benefits for working beneficiaries can be reduced or withheld months later, even if that occurs after a worker’s job has ended and the individual badly needs his or her benefits for living expenses.[19]

-

Beneficiaries could have significant earnings and still collect disability benefits. A beneficiary at the 75th percentile of benefits (about $1,500 a month) could earn up to $3,000 a month — or $36,000 a year — and still get a $150 monthly benefit.[20] Although this wouldn’t happen very often, it may be difficult to justify paying disability benefits to people with earnings at those levels.

In short, it isn’t clear that a benefit offset starting below SGA would be a positive change; it could easily do more harm than good. Some people would work more. But others, facing what amounts to a 50 percentage-point increase in their marginal tax rate, might work less. In light of these concerns, backers of a $1-for-$2 offset who are serious about evidence-based policymaking should refrain from enacting it before it is rigorously tested and evaluated.