Obama Budget Restores Housing Vouchers

Targets Vouchers to Reduce Homelessness, Help Victims of Domestic Violence, Keep Families Together

End Notes

[1] David Reich and Joel Friedman, “President’s Sequestration Relief Would Ease Austerity Without Raising Deficits,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 3, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=5264, and David Reich, “Sequestration and Its Impact on Non-Defense Appropriations,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 19, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=5272. Funding for non-defense discretionary programs would nevertheless continue to fall over the next several years to a historically low level, measured as a share of GDP, under the President’s proposal.

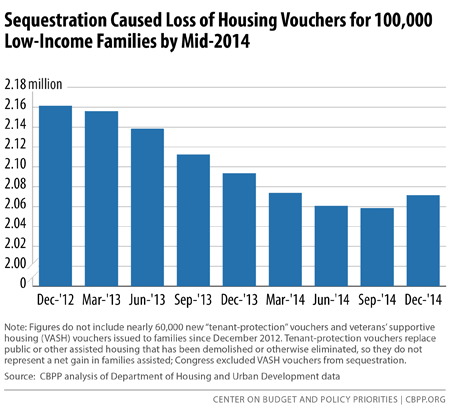

[2] As the 2011 Budget Control Act required, the Office of Management and Budget implemented across-the-board sequestration cuts in March 2013. Sequestration reduced funding for the renewal of Housing Choice Vouchers by $858 million — equivalent to funding for some 110,000 vouchers.

[3] CBPP estimates from HUD data. The estimates do not count nearly 60,000 new “tenant-protection” vouchers and veterans’ supportive housing (VASH) vouchers that HUD awarded to state and local housing agencies (and that agencies then issued to families) from December 2012 to December 2014. Tenant-protection vouchers replace public or other assisted housing that has been demolished or eliminated for other reasons; our analysis of sequestration’s impact does not include these vouchers because they do not represent a net gain in the number of families receiving assistance. We also did not count new VASH vouchers, as Congress excluded VASH vouchers from sequestration and our intent is to isolate the effects of sequestration on local rental assistance resources.

[4] In addition to giving housing agencies sufficient funds to renew vouchers at their average leasing levels and costs during calendar year 2014, the 2015 law directed HUD to provide supplemental funds for agencies assisting more families at the end of 2014 or early 2015 than over calendar year 2014, on average; it also set aside a portion of renewal funds for this purpose. This provision will help agencies that were restoring vouchers to use in 2014.

[5] More than 70,000 families were seeking rentals with vouchers in hand from July through December, or more than 25,000 above the monthly average for the two years before sequestration.

[6] In six of the past eight years, Congress has authorized HUD to reduce renewal funding for agencies with excess reserves of unspent funds, and HUD has implemented reserve offsets in four of those years (2008, 2009, 2012, and 2014). Policymakers recognize that it is prudent for agencies to maintain modest reserves to ensure that assistance payments for vouchers that families are using will not be interrupted due to unexpected changes in leasing or costs. However, they have frowned on the accumulation of reserve balances that exceed 8 percent of annual costs, and have proposed at times to limit reserves to as low as 6 percent, although smaller agencies, which can experience greater cost volatility, receive greater leeway.

[7] Families contribute roughly 30 percent of their income for housing costs; the voucher fills the gap between this contribution and the actual rent and utility costs of the unit, within reasonable limits set by HUD and the local housing agency. This system ensures that housing will remain affordable to families as their incomes rise and fall, while also making sure that the federal subsidy is no higher than needed to meet this goal.

[8] These included VASH vouchers for homeless veterans; “tenant protection” vouchers, which HUD issues to agencies in communities that lose other types of federally assisted housing (for instance, when public housing is demolished); and Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) conversion vouchers, which HUD issues to public or private owners of assisted housing that are converting from federal subsidy streams to project-based vouchers as part of RAD, which Congress first authorized in 2012. Note that the transfer of funding from the public housing to the voucher programs covers the costs of RAD vouchers associated with public housing conversions.

[9] These figures are based on the CPI for residential rents and household fuels and utilities, weighted to reflect the fact that the former constitutes about 85 percent of rental costs and the latter 15 percent, according to the Consumer Expenditure Survey. The CPI figures cited are roughly consistent with the long-term trend estimate of 2.3 percent that HUD used in calculating Fair Market Rents for 2015.

[10] To fullyoffset the effect of inflation in rent and utility costs — so that voucher costs don’t rise at all in nominal terms — household incomes would typically have to rise about three times faster than rent and utility costs, an extremely unlikely occurrence. Consider, for instance, that about half of voucher households live on Social Security or other fixed income sources, and Social Security cost-of-living adjustments have averaged 1.7 percent over the past five years. While annual increases in the average per-voucher subsidy recently have been well below CPI increases in rents and utilities in recent years, this has had little to do with rental costs or tenant incomes. Rather, funding shortfalls due to sequestration have forced housing agencies to take actions that have effectively suppressed subsidy costs; for instance, many agencies have reduced or frozen their “payment standards” — which determine the maximum subsidy that families using vouchers may receive — thereby preventing voucher subsidies from rising in accord with increases in local rents. Agencies cannot sustain this over the long term without significantly increasing rent burdens for assisted families and reducing their ability to find suitable housing in which to use their vouchers. It is therefore reasonable to expect — and essential to the program’s effectiveness — that per-voucher costs return closer to the market norm over time.

[11] With the additional 20,000 VASH vouchers that Congress funded in 2014 and 2015, the Administration argues, communities will have sufficient capacity to eliminate homelessness among veterans who are eligible for VASH. The President’s targeted voucher proposal, recognizing that some homeless veterans are ineligible for VASH — for instance, because of their service discharge status or because they are in communities where VASH vouchers are not available — would make such veterans eligible for assistance.

[12] Since 2010, chronic homelessness has declined by 21 percent. The President’s budget includes a $345 million increase for homeless assistance grants, most of which would be directed to create 25,500 new units of supportive housing for chronically homeless individuals.

[13] For example, see Aaron C. Davis and Julie Zauzmer, “With 4,000 in homeless shelters, D.C. on pace to eclipse record set last year,” Washington Post, January 29, 2015, http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/dc-politics/with-4000-in-homeless-shelters-dc-on-pace-to-eclipse-record-set-last-year/2015/01/29/e74de4ca-a7c4-11e4-a06b-9df2002b86a0_story.html; and Laila Kearney, “New York City sees record number of children in homeless shelters,” Reuters, March 19, 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/03/19/us-usa-new-york-homelessness-idUSKBN0MF2JH20150319.

[14] National Center for Homeless Education, “Education for Homeless Children and Youth Consolidated State Performance Report Data: School Years 2010-11, 2011-12, and 2012-13,” September 2014, http://center.serve.org/nche/pr/data_comp.php.

[15] Office of Policy Development and Research, “Study of PHAs’ Efforts to Serve People Experiencing Homelessness,” Department of Housing and Urban Development, February 2014.

[16] U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, “Opening Doors Update 2013, Appendix,” April 2014; and congressional justifications for the President’s budget for fiscal year 2016.

[17] The President’s proposal would require that agencies receiving targeted vouchers either demonstrate that they participate in the local continuum of care or are an eligible recipient of Native American Housing Block Grant funds. Housing agencies that are working with local school liaisons who work with homeless children and their families and are funded under the McKinney Act should also be made eligible. The Administration’s vision of how the housing vouchers for tribal families would be administered or used is unclear, as the budget proposal requests broad waiver authority and states that the voucher assistance for tribal families “shall be subject to requirements of NAHASDA” (the Native American Housing and Self Determination Act).

[18] Patrick J. Fowler and Dina Chavira, “Family Unification Program: Housing Services for Homeless Child Welfare–Involved Families,” Housing Policy Debate, Vol. 24, No. 4, 802–814 (2014).

[19] National Center for Housing and Child Welfare, http://www.nchcw.org/uploads/7/5/3/3/7533556/fup_cumulative_list.pdf.

[20] Under the “fair share” formula, each state or sub-state area received an allocation of vouchers, which HUD distributed to individual agencies via a competition.

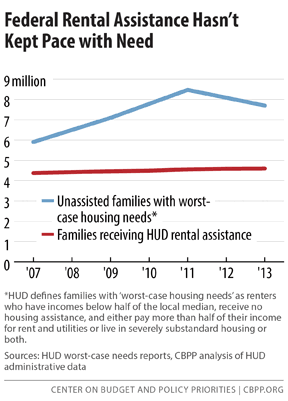

[21] Office of Policy Development and Research, “Worst Case Housing Needs, 2015 Report to Congress: Executive Summary,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2015, http://www.huduser.org/portal/Publications/pdf/WorstCase2015_summary.pdf.

[22] See, for example, http://kxan.com/2014/10/31/city-gets-more-than-19000-applications-for-housing-assistance/, http://www.indystar.com/story/money/2014/10/24/section-waiting-list-flooded-applications/17853629/, http://blogs.seattletimes.com/today/2015/02/king-county-housing-authority-buried-in-section-8-applications/, and http://www.startribune.com/local/293936331.html.

[23] The combined Consumer Price Indices (CPI) for residential rents and utility costs rose 9.9 percent from fiscal year 2010 to 2014, slightly above the general CPI change of 8.6 percent. The relative modesty of the President’s request is explained by the very low rates of inflation in per-voucher costs since 2010, relative to market rent and utility costs.