más allá de los números

Can Governor Romney’s Tax Plan Do All That He Says It Will?

We’ve issued an analysis of the new tax plan from Governor Mitt Romney. Here’s the opening:

Unveiling his tax plan on February 22, Governor Romney’s campaign said it would: 1) make permanent President Bush’s tax cuts (but not those enacted under President Obama’s, which are scheduled to expire at the same time and which expanded several refundable tax credits for low- and middle-income families); 2) then cut individual income tax rates 20 percent below the Bush levels, reducing the Bush top rate of 35 percent to a new top rate of 28 percent; 3) repeal the estate tax; 4) repeal the Alternative Minimum Tax; 5) cut the top corporate tax rate by nearly 30 percent (from 35 to 25 percent); and 6) scale back unspecified “tax expenditures,” mainly for high-income people. It would leave untouched the biggest tax break for high-income households — the 15 percent tax rate on capital gains and dividends — and eliminate capital gains taxes altogether for people with incomes below $200,000. Governor Romney’s advisers also said the plan would preserve “revenue neutrality” and maintain the current degree of progressivity in the tax code.

As experts at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (TPC) have noted, it would be virtually impossible to achieve all of the plan’s multiple goals at the same time. In particular, the Romney tax policy changes would almost certainly add substantially to the deficit. Assessing the plan, the TPC’s Roberton Williams observed, “Nothing comes to mind to broaden the tax base enough to pay for the lower rates.”

Now, a new TPC analysis (issued March 1) backs up the skepticism with hard facts. It finds that, absent base broadeners, the Romney plan would cut taxes by $481 billion in 2015 alone, translating into a $4.9 trillion revenue loss over the coming decade. Most tax experts believe that’s far more than any conceivable set of base-broadeners (i.e., reductions in tax expenditures) could generate, leaving the Romney plan as not “revenue neutral” but, instead, a significant revenue loser.

Moreover, a close reading of the document from the Romney campaign about the plan, as well as Governor Romney’s February 23 op-ed in the Wall Street Journal and statements by Romney campaign advisor Glenn Hubbard, suggest that the plan is not, in fact, intended to be revenue neutral. Neither the campaign document nor the Romney op-ed actually says it is. Instead, both state: “Stronger economic growth and reductions in spending will help to ensure that these tax cuts do not expand deficits.” In other words, along with scaling back unspecified tax expenditures, the plan relies in substantial part on “dynamic scoring” — an assumption that tax cuts will boost economic growth and, in turn, federal tax revenues — and very deep budget cuts to avoid expanding the deficit.

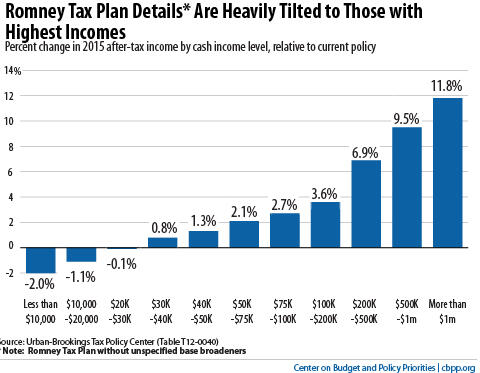

Finally, the Romney plan would significantly exacerbate the already serious problem of income inequality in America, conferring extraordinarily large tax cuts on the wealthiest Americans while raising taxes on people making less than $30,000 a year. TPC estimates that people who make over $1 million a year would get an average tax cut of $250,000 in 2015 (increasing their after-tax income by an average of almost 12 percent), while people making between $40,000 and $50,000 would get an average tax cut of $512 (increasing their after-tax income by an average of 1.3 percent), and people making between $10,000 and

$20,000 would pay an average $174 more in taxes (decreasing their after-tax income by an average of 1.1 percent).

Click here for the full report.