Ten Facts You Should Know About the Federal Estate Tax

End Notes

[1] Brandon DeBot and Nathaniel Frentz contributed to previous versions of this report.

[2] The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2013 set the estate tax exemption at $5.25 million for 2013 (effectively $10.5 million for a couple), and indexed that level for inflation in future years. It set the top rate at 40 percent. See Internal Revenue Bulletin 2013-5, Revenue Procedure 2013-5, January 2013, http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-13-15.pdf.

[3] For more on how repeal of the federal estate tax would affect states, see Iris J. Lav, “Repealing Federal Estate Tax Would Likely Deprive States of Needed Revenues and Tilt Tax Systems Toward Wealthy,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised May 2, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/repealing-federal-estate-tax-would-likely-deprive-states-of-needed.

[4] Joint Committee on Taxation, “History, Present Law, and Analysis of the Federal Wealth Transfer Tax System,” March 16, 2015, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4744.

[5] Lily L. Batchelder, “The ‘Silver Spoon’ Tax: How to Strengthen Wealth Transfer Taxation,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, Delivering Equitable Growth: Strategies for the Next Administration, October 31, 2016, https://ssrn.com/abstract=2862144.

[6] Tax Policy Center Table T17-0230.

[7] See these CBPP reports: Chye-Ching Huang, “Congress Should Not Weaken Estate Tax Beyond 2009 Parameters,” March 11, 2009, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=2356; Aviva Aron-Dine and Joel Friedman, “New Estate Tax Anecdotes Dredge Up Old Myth That the Estate Tax Claims Half of an Estate,” June 14, 2006, https://www.cbpp.org/6-14-06tax.htm; Chye-Ching Huang, “Impact of Estate Tax on Small Businesses and Farms Is Minimal,” February 23, 2009, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=2663.

[8] Zachary Mider, “How Wal-Mart’s Waltons Maintain Their Billionaire Fortune,” Bloomberg, September 12, 2013, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-09-12/how-wal-mart-s-waltons-maintain-their-billionaire-fortune-taxes.html.

[9] Estimate by Richard Covey. See Zachary Mider, “Accidental Tax Break Saves Wealthiest Americans $100 Billion,” Bloomberg, December 17, 2013, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-12-17/accidental-tax-break-saves-wealthiest-americans-100-billion.html.

[10] For a description of other loopholes and proposals to close them see: President Obama’s fiscal year 2017 budget; S. 1677, introduced by Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) on June 25, 2015; and Paul Caron and James Repetti, “Revitalizing the Estate Tax: Five Easy Pieces,” Tax Analysts, March 17, 2014.

[11] Tax Policy Center Table T16-0230.

[12] Congressional Budget Office, Effects of the Federal Estate Tax on Farms and Small Businesses, July 2005, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/16897.

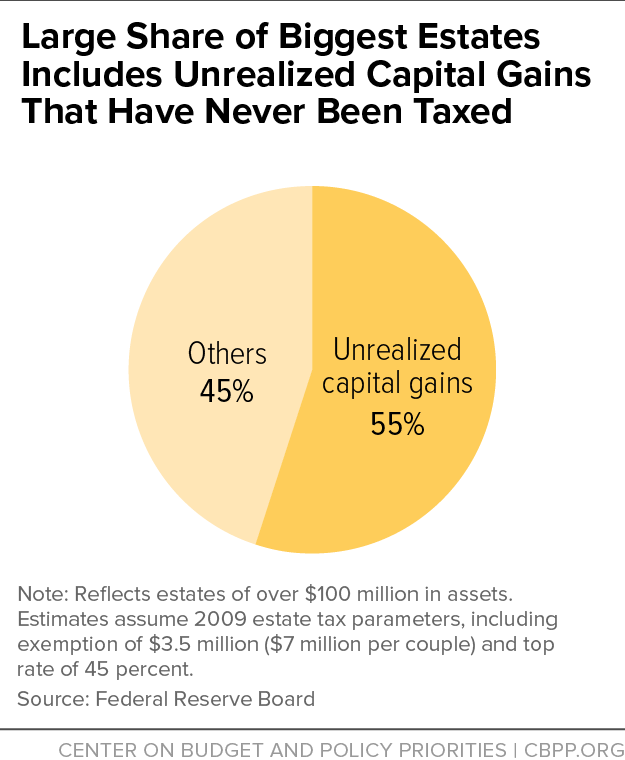

[13] President Obama’s 2017 budget proposed to repeal this favorable treatment, known as “step-up basis,” and raise the top tax rate on capital gains to 28 percent. For more on this proposal, see Chuck Marr and Chye-Ching Huang, “President’s Capital Gains Tax Proposals Would Make Tax Code More Efficient and Fair,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 18, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=5260.

[14] Robert B. Avery, Daniel Grodzicki, and Kevin B. Moore, “Estate vs. Capital Gains Taxation: An Evaluation of Prospective Policies for Taxing Wealth at the Time of Death,” Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs, Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C., Finance and Economics Discussion Series, April 2013; and James Poterba and Scott Weisbenner, “The Distributional Burden of Taxing Estates and Unrealized Capital Gains At the Time of Death,” NBER, July 2000, p. 19, http://www.nber.org/papers/w7811.

[15] Tax Policy Center Table T17-0137.

[16] Chye-Ching Huang and Chuck Marr, “Raising Today’s Low Capital Gains Tax Rates Could Promote Economic Efficiency and Fairness, While Helping Reduce Deficits,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 19, 2012, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3837.

[17] Congressional Budget Office, “An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: 2016 to 2026,” August 23, 2016, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/51908.

[18] Joint Committee on Taxation, JCX-68-15, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4761.

[19] Jane G. Gravelle and Donald J. Marples, “Estate and Gift Taxes: Economic Issues,” Congressional Research Service, November 27, 2009.

[20] See Aviva Aron-Dine, “Estate Tax Repeal Would Decrease National Saving,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 8, 2006, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=352.

[21] Relative to 1999, estate tax revenues are now lower, but there are also fewer taxable estates, and those that are taxable are also much larger on average due to the higher exemption level. As a result, there is no reason to believe that compliance costs as a share of estate tax revenue are necessarily much higher today.

[22] See Joel Friedman and Ruth Carlitz, “Cost of Estate Tax Compliance Does Not Approach the Total Level of Estate Tax Revenue,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised June 9, 2006, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=389.

[23] See Charles Davenport and Jay A. Soled, “Enlivening the Death-Tax Death-Talk,” Tax Notes, vol. 84, July 26, 1999; and Richard Schmalbeck, “Avoiding Federal Wealth Transfer Taxes,” in William G. Gale, James R. Hines, Jr., and Joel Slemrod, eds., Rethinking Estate and Gift Taxation, Brookings Institution, 2001.

[24] Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, “Revenue Statistics — Comparative tables,” retrieved April 2017, http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REV. Although the United States has a higher top statutory estate tax rate than some other OECD countries, its effective tax rate is lower and the tax reaches relatively few estates. Also, many countries tax accumulated wealth by means of wealth or wealth transfer taxes (such as inheritance taxes) rather than through an estate tax, so international comparisons must take these other taxes into account. Further, some countries levy taxes on a broader tax base than others (that is, they allow fewer exemptions and other special preferences). For all of these reasons, experts generally agree that the appropriate way to compare taxes across countries is to look at revenues as a share of gross domestic product, not at statutory tax rates.

[25] According to the Tax Policy Center estimates, over 90 percent of the estate tax is paid by the top 10 percent of taxpayers. See “Who pays the estate tax?” Tax Policy Center Briefing Book, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/who-pays-estate-tax.

[26] Lily Batchelder, “Reform Options for the Estate Tax System: Targeting Unearned Income,” testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, March 12, 2008. Also see “What Should Society Expect From Heirs? A Proposal For A Comprehensive Inheritance Tax,” New York University School of Law and Economics Research Paper No. 08-42, October 2008, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1274466.

[27] Excerpts from a CBPP conference call, June 1, 2006, https://www.cbpp.org/6-1-06tax-transcript.pdf.