- Home

- Better Cost Estimates, Better Budgets

Better Cost Estimates, Better Budgets

Improved Fiscal Notes Would Help States Make More Informed Decisions

State legislators need accurate and useful information about the cost of spending- and tax-related proposals to make good decisions about the proposals. Nearly all states produce some sort of cost estimate of bills, typically called a “fiscal note,” but in many states these estimates are not very useful. For example, they often fail to estimate the cost beyond the next year or two, they are not revised when the legislation is amended, or they are only produced for a narrow set of bills.

This lack of information can cause legislators to enact proposals that cause serious fiscal problems, harming states’ ability to provide for the high-quality education systems, roads and bridges, and other public investments that provide a foundation for strong economic growth. For example, the cost of new programs or tax changes may turn out to exceed the state’s ability to pay, causing unnecessary fiscal stress. Or a new program or tax change may be affordable for a year or two, and then balloon in cost later, causing a crisis that could have been avoided if lawmakers had more complete information.

This sort of information also can help the public more easily track and evaluate proposed legislation. This additional level of review of the costs and benefits of proposed legislation will further help the state avoid major mistakes and increase the chances that newly enacted laws will serve the public’s interest.

States could improve their fiscal notes by adopting the following practices:

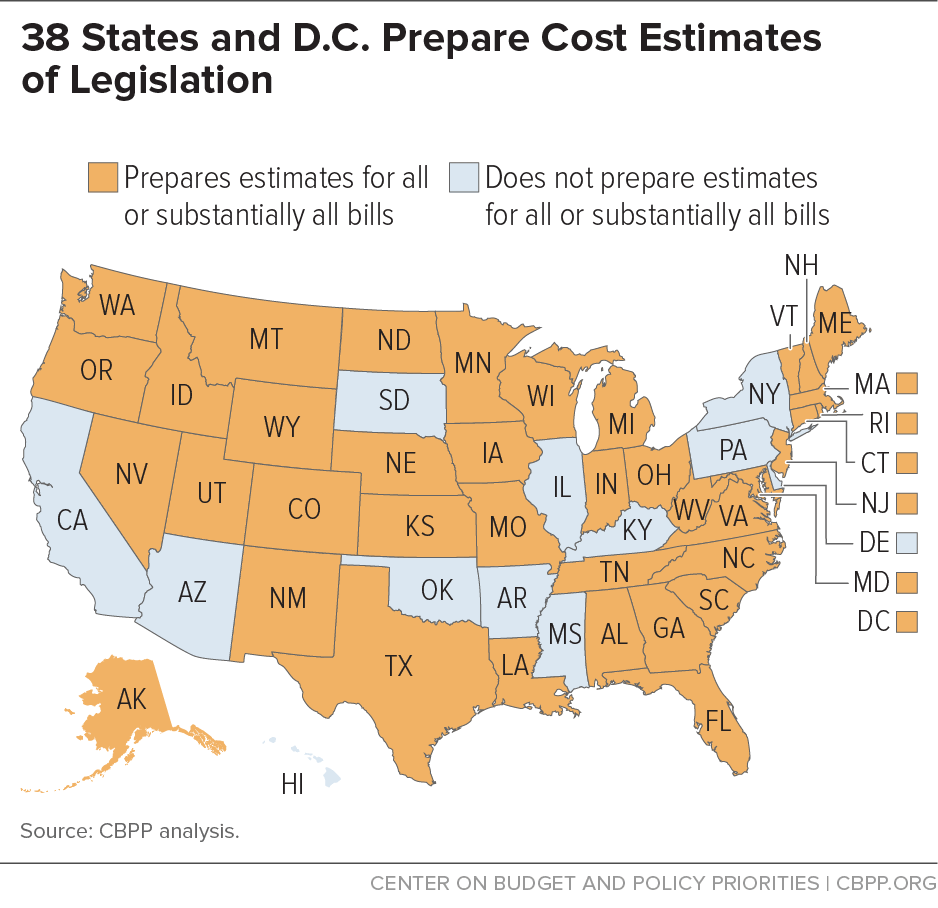

- Prepare fiscal notes for all proposals. Legislators need to know the costs of any bill that will affect revenue or spending to decide on its merits, to determine if it is affordable in its current form or if it needs modification to become affordable, and to plan for the future. In 38 states and the District of Columbia, fiscal notes are routinely prepared for all or substantially all bills that would have a significant fiscal impact.

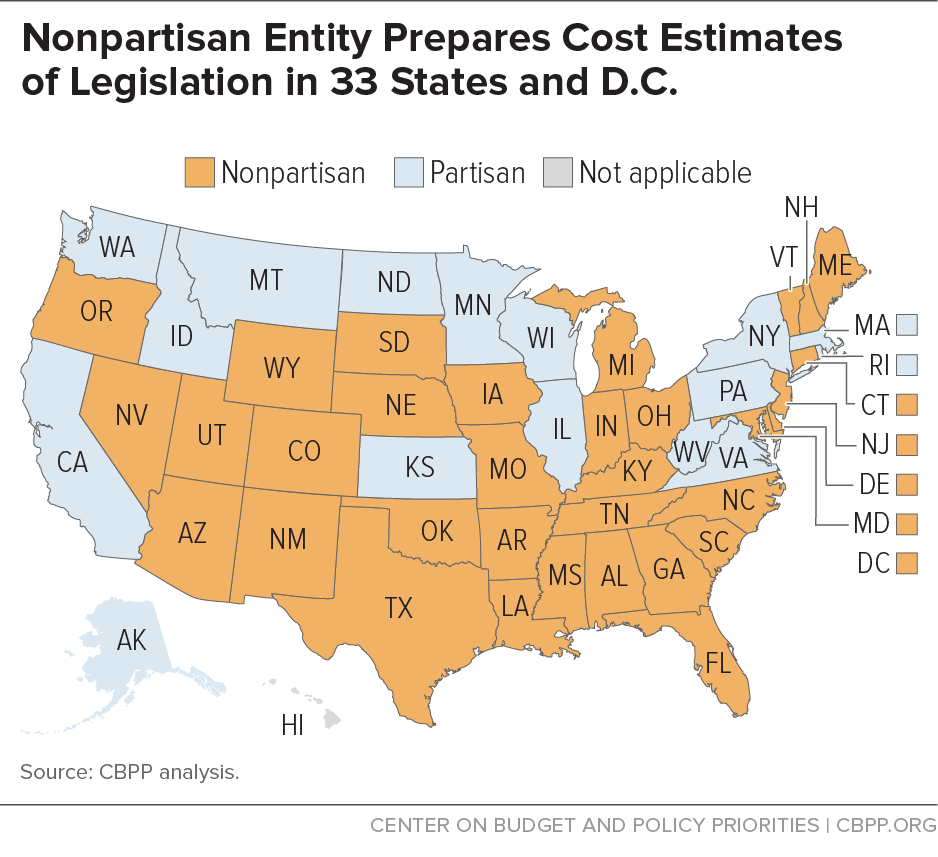

- Free estimates from partisan pressure. If legislators and the public are not convinced that the fiscal notes are of high quality and free from bias, they may ignore them. Having a well-staffed, professional office or group prepare the fiscal notes goes a long way to ensuring that the fiscal notes reflect the best possible information on a proposed bill’s impact. The estimates that a non-partisan office prepares without political pressure will engender more confidence. Most states (33 and the District of Columbia) assign the task of preparing fiscal notes to a nonpartisan legislative fiscal office or other nonpartisan entity. But 16 states do not, allowing for the possibility that the fiscal notes could be affected by partisanship.

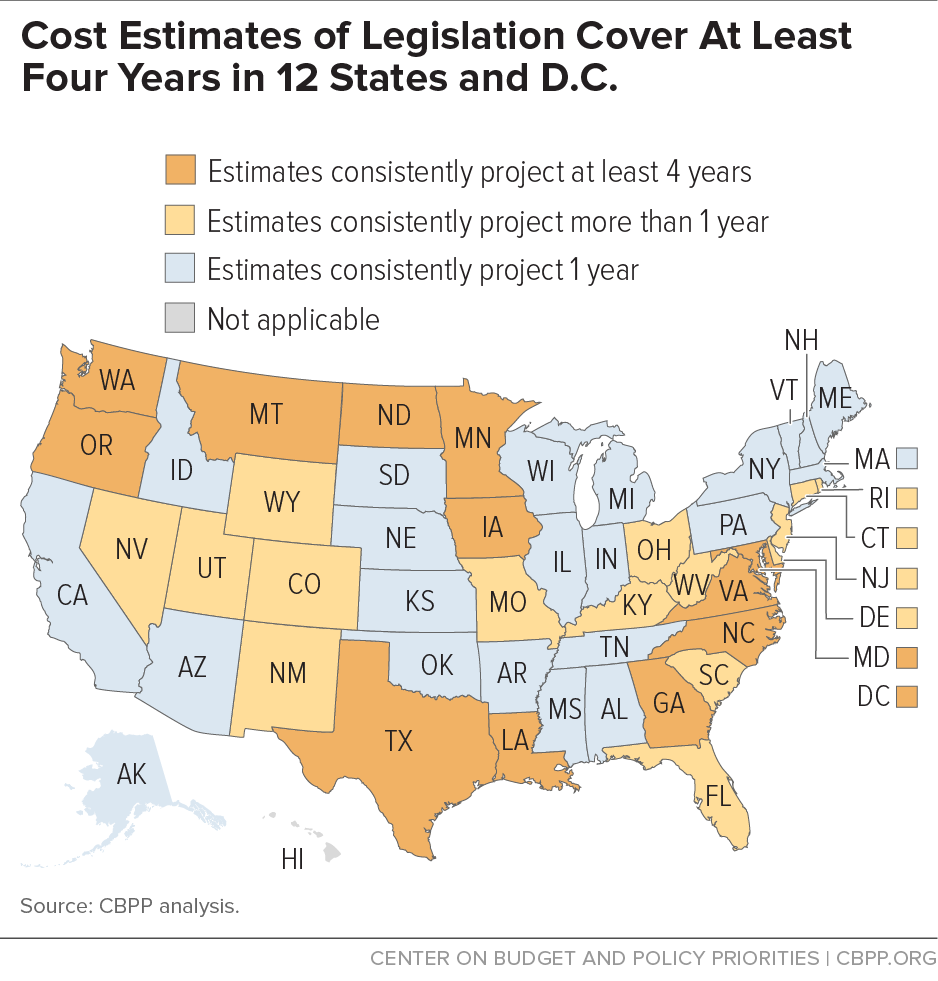

- Project long-term impact. Fiscal notes should reflect the cost of the proposed legislation when fully in effect. That often requires looking beyond the impact on the next one or two fiscal years, because the costs may rise rapidly in the years beyond those covered by a short-term fiscal note. Twelve states and the District of Columbia routinely include four or more years in their fiscal notes.

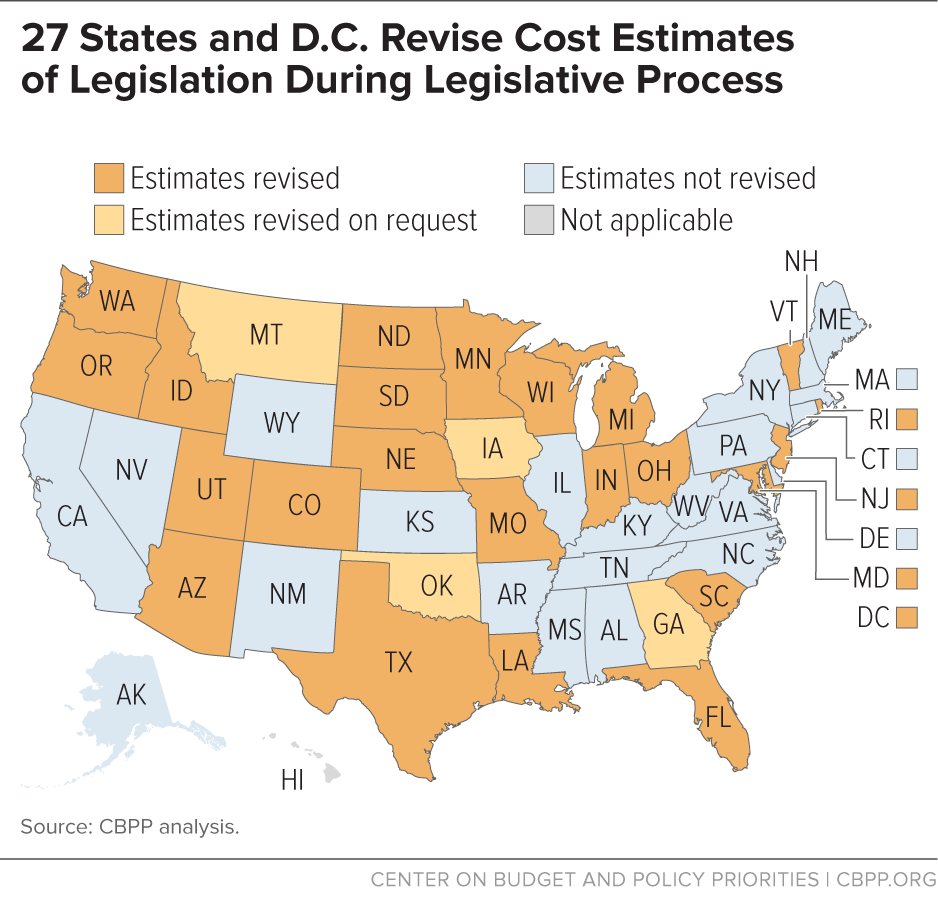

- Revise estimates as needed. Proposed legislation is often modified or amended as it goes through the legislative process. If a fiscal note is not updated for material changes in a bill, the note no longer serves its purpose. Only slightly more than half the states (27 states and the District of Columbia) regularly revise fiscal notes for changes in proposed legislation.

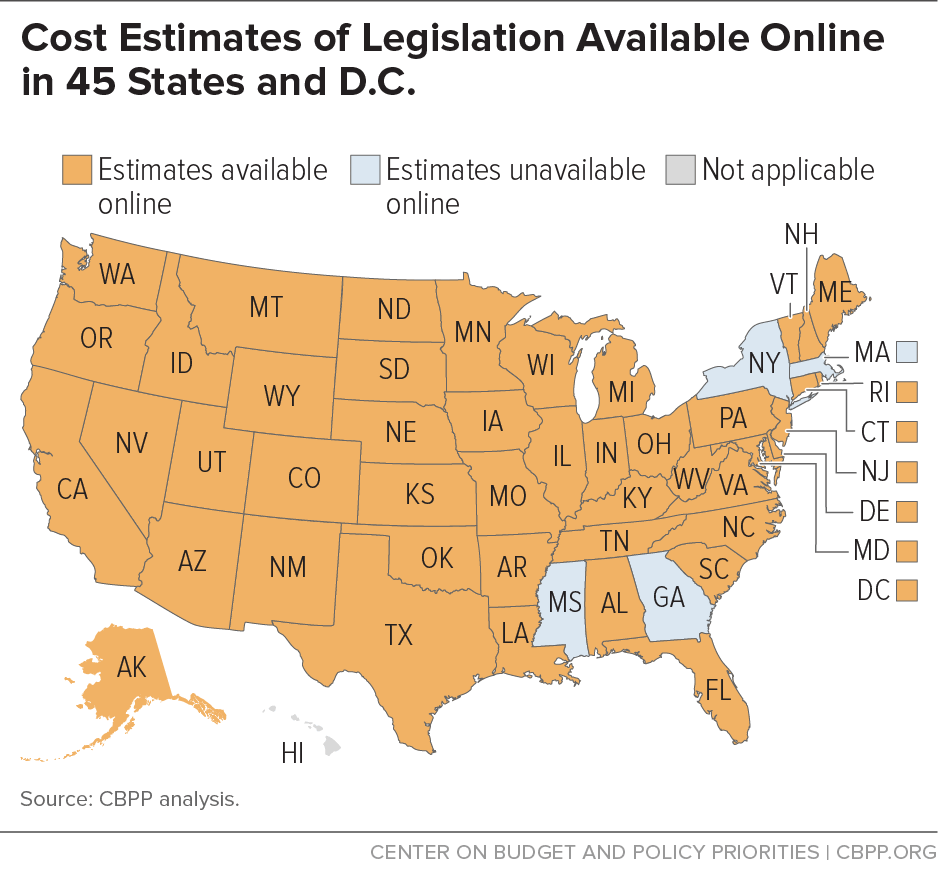

- Post fiscal notes online. Most states post their fiscal notes on the Internet in a manner that is accessible to the general public. Only four of the states that prepare fiscal notes — Georgia, Massachusetts, Mississippi, and New York — do not post them on the Internet.[1]

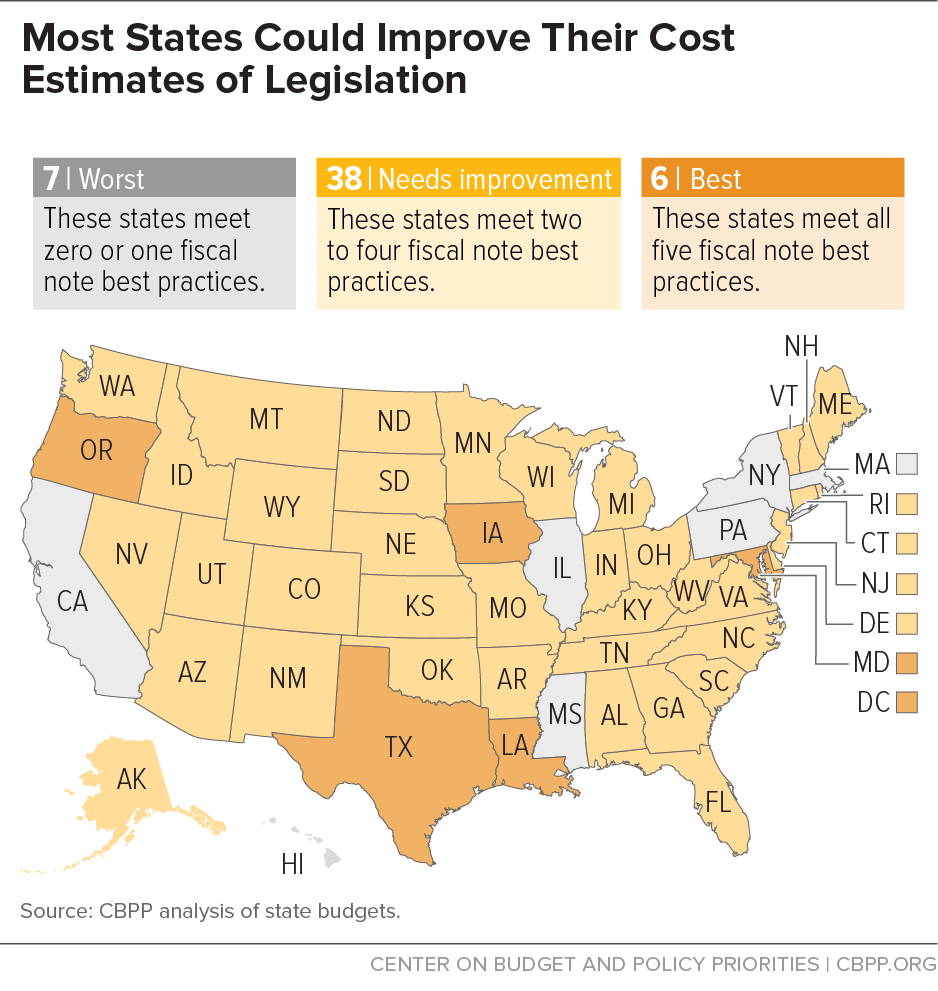

Five states ― Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, Oregon, and Texas ― and the District of Columbia meet all of these best practices. Seventeen other states meet four of the five best practices criteria, and could upgrade their practices with a modicum of effort. At the other end of the spectrum, seven states meet just one or none of these practices.[2] (See Figure 1. Also see Table 1 and the interactive map at the end of this report.)

Additionally, the existence of a law or legislative rule and a written procedure for preparing fiscal notes can help ensure that states prepare fiscal notes for all appropriate legislative proposals. While all states except California and Hawaii have a statutory or legislative rule relating to fiscal notes, some are quite limited. Some states require fiscal notes only for bills relating to pensions or bills affecting businesses, for example, but may sometimes provide estimates for other types of legislation.

Other issues also arise with respect to fiscal notes. Some states provide information on how state legislation would affect local government budgets. One state, Texas, analyzes the impact of revenue legislation on residents at different income levels. Finally, some states have experimented with using a “dynamic score” that attempts to consider macroeconomic impacts of legislation — a practice that can be misleading if used for an official score.

Fiscal Notes Are Critical to the Legislative Process

The National Conference of State Legislatures describes fiscal notes as:

A fiscal note provides a reliable estimate of the impact a bill or resolution will have on state revenues and expenditures. A bill with a fiscal impact may increase or reduce expenditures; increase or decrease the revenues of an existing tax; change personnel requirements; affect levels of service; impose or shift a tax to a new base; or change the funding of an existing program.[3]

In all of these situations, legislators need fiscal notes to decide on a bill’s merits, to assess its affordability, and to plan for the future. Fiscal notes also enable other interested parties to weigh in, in a more informed manner, on the legislative process. And they allow the media to understand and report accurately on pending legislation’s importance.

Preparing high-quality fiscal notes requires a state to have a staff with an appropriate level of expertise and the ability to prepare analyses quickly during the legislative session. In many states, this expert staff is located in a nonpartisan legislative fiscal office. In other states, the locus of expertise is in the executive branch or legislative committee staff.

Preparing fiscal notes is well worth the effort and critical to a well-functioning legislative process.Preparing fiscal notes is well worth the effort and critical to a well-functioning legislative process. They have led legislators to modify bills to reduce costs, to reject some bills as too expensive, and to plan ahead to accommodate future costs when an expensive piece of legislation is passed.

Almost All Proposals Need Fiscal Notes

Fiscal notes are routinely prepared for all or substantially all bills that would have a significant fiscal impact in 38 states and the District of Columbia.[4] (See Figure 2 and Table 1.) In most of these states, a fiscal note is prepared whenever a bill is introduced. In others, it is required when a bill is heard by a committee (Florida), or is approved by a committee (Connecticut and Massachusetts).

The other 12 states require fiscal notes in varying circumstances. Some states limit the types of bills to be analyzed. For example, Arkansas requires fiscal notes only for bills affecting retirement; it may prepare notes on tax bills if a legislator requests a note. New York requires fiscal notes only for pension bills. Washington requires fiscal notes for revenue bills and for bills that affect incarceration rates or public employee benefits, but not for appropriation bills. California has no requirement for fiscal notes, but legislative committee staff occasionally prepare them. Other states prepare fiscal notes only on request. For example, fiscal notes are prepared in Illinois only if the bill sponsor requests the note or another legislator has the backing of the body’s majority to request the note. (See notes to Table 1.) Rules that limit notes to particular types of spending leave many bills that affect a state’s budget unanalyzed. Relying on a request also may leave important bills unanalyzed, and could politicize the fiscal note process.

A Nonpartisan Agency or Office Should Prepare Fiscal Notes

It is critical that policymakers, the public, and other interested parties can rely upon the fiscal notes that are prepared to reflect the best possible information and analysis of the impact of a proposed bill. If legislators and the public are not convinced that the fiscal notes are of high quality and free from bias, they may ignore them, and legislation may be enacted that harms the state’s fiscal condition.

Having a nonpartisan entity prepare the fiscal notes is an important underpinning of having fiscal notes that all interested parties can rely upon. Most states follow that practice, primarily through assigning fiscal note preparation to a nonpartisan legislative fiscal office. (See Figure 3.) In 16 states, however, the fiscal notes are prepared within the executive branch, such as a budget office or affected agency, or legislators themselves or legislative committees prepare the notes. These practices may result in partisan fiscal notes. When the executive branch — especially the same office that prepares the governor’s budget — prepares fiscal notes, the staff could be subject to implicit political pressure to report a favorable score for a governor’s high-priority proposal or an unfavorable score for a competing proposal. And legislative committee staff are generally partisan.

For example, fiscal notes are prepared in an office of the executive branch that also is involved in the development of the governor’s budget in Alaska, California, Kansas, Minnesota, Montana, New York, Rhode Island, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin. In Illinois and North Dakota, the affected executive branch agency prepares the estimate. In Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, legislative committees rather than a nonpartisan legislative office prepare the fiscal notes.

Fiscal Notes Should Estimate Legislation’s Long-Term Effects

Fiscal notes should reflect the proposed legislation’s full cost. That often requires looking beyond the impact on the next one or two fiscal years, because the costs may rise rapidly in the years beyond those covered by a short-term fiscal note. Twelve states and the District of Columbia routinely include four or more years in their fiscal notes: Georgia, Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, Minnesota, Montana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oregon, Texas, Virginia, and Washington. (See Figure 4.)

The effects of many types of legislation phase in over time; it is common, for example, for tax proposals to gradually reduce certain rates over the subsequent three, four, five, or more years. Missouri in 2014 enacted a personal and business income tax cut that will phase in over five years beginning in 2017, so the full effect of the legislation will not occur until eight or nine years after enactment.[5] In 2013, Kansas enacted a five-year phase-in of income tax rate cuts. In 2011, Arizona enacted a phased-in corporate income tax cut that begins in 2015 and reaches full effect in fiscal year 2018, seven years after enactment. Many other state legislatures over the years have enacted or debated tax reductions that are phased in over several future years.

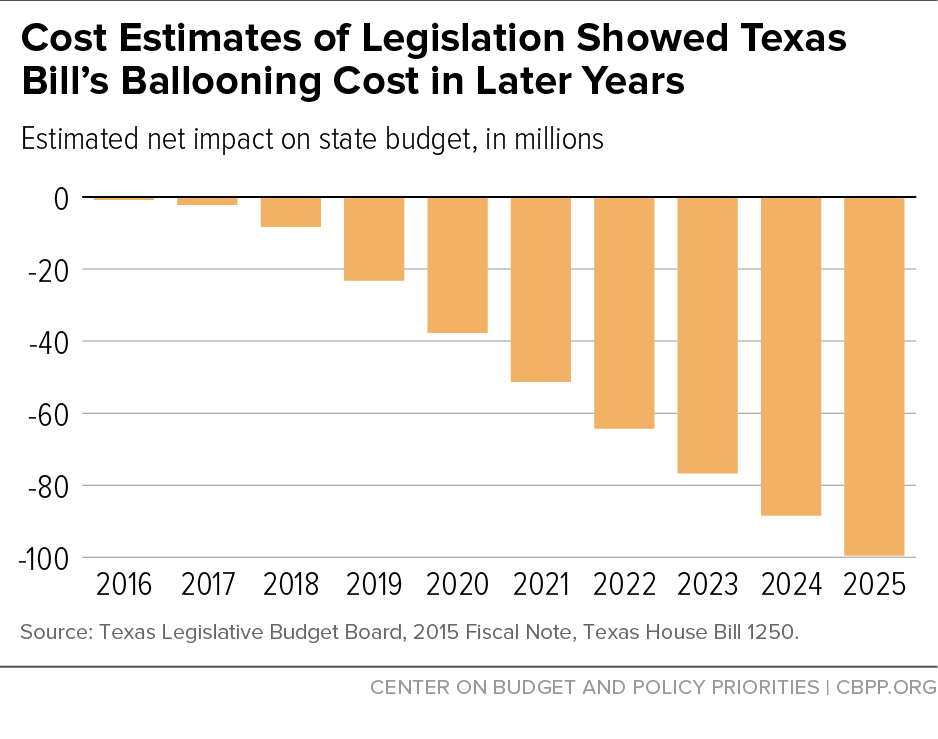

An economic development bill considered in the Texas House in 2015, for example, would have loosened the new job creation and wage standards in current law to make it easier for businesses to qualify for a multi-year property tax break. The Legislative Budget Board, the state’s nonpartisan legislative fiscal office, prepared a ten-year estimate of the cost to the state general fund. It found the cost in 2016 would be $509,000 and the cost in the biennium ending August 31, 2017 would be $2.7 million. But it also found that the cost would grow each year, reaching close to $100 million a year in 2025.[6] (See Figure 5.) Legislators and the public would have been severely misled had they had information only on the first year or first biennium’s cost. But with the fiscal note’s ten-year information, legislators could decide whether the job creation would be worth the cost.[7]

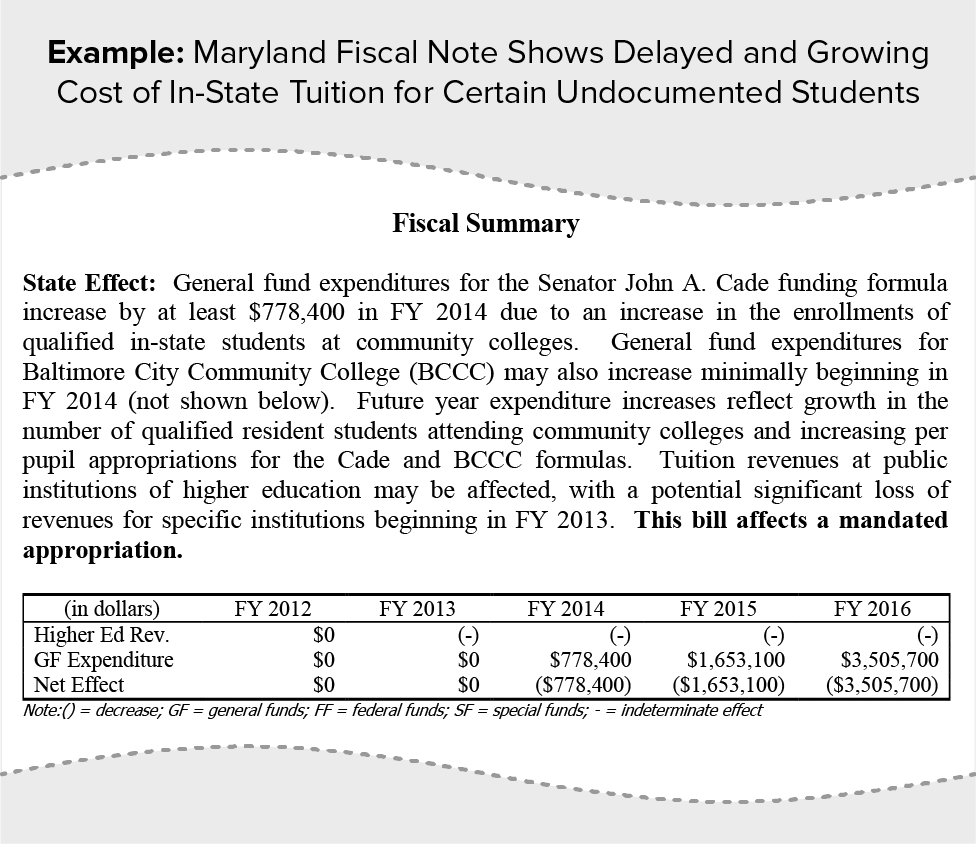

Some new programs or program expansions also phase in over time, as they expand to benefit new groups of people or new areas of the state. These, too, require multi-year estimates to fully understand their impact on the budget. For example, in 2011 Maryland enacted legislation to allow certain undocumented individuals who graduate from a Maryland high school to pay in-state tuition rates at community colleges and ultimately at four-year institutions. The fiscal note showed that the cost would grow as more people became eligible for the reduced tuition and took advantage of it. The legislation was effective on July 1, 2011. The fiscal note found that the first annual cost of approximately $778,000 would occur in fiscal year 2014, rising to $3.5 million in fiscal year 2016.[8] (See Figure 6.) In this example, a one- or two-year fiscal note would not have been useful. In fact, in this case even the five-year fiscal note leaves the observer wondering about the rate at which costs will rise beyond the fifth year. Nevertheless, legislators were able to see that costs would grow over the years, and made the decision that the policy was worth the cost.

Fiscal Notes Should Be Revised as Needed

Fiscal notes should reflect the most current version of legislation. Proposed legislation is often modified or amended as it goes through the legislative process. If a fiscal note is not updated for material changes in a bill, the note will no longer serve its purpose. Nevertheless, only slightly more than half the states (27 states and the District of Columbia) regularly revise fiscal notes for changes in proposed legislation. (See Figure 7.)

The states that require revisions do so in a variety of ways. Some states require revisions when a bill is amended. Others require revisions at certain points in the process, such as when a bill is reported out of committee. To provide the best possible information, fiscal notes should be updated whenever a bill is changed in any way.

Fiscal Notes Should Be Easily Accessible to the Public

The vast majority of states that prepare fiscal notes post them on the Internet in a manner that is accessible to the general public. Only four of the states that prepare fiscal notes — Georgia, Massachusetts, Mississippi, and New York — do not post them on the Internet.[9] (See Figure 8.) As a result, these states make it unnecessarily difficult for the public, media, and others to engage in the policymaking process. The states that do post fiscal notes can make them more accessible by showing the fiscal notes for all stages of the bill in one place.

Laws, Rules, and Written Procedures Ensure That Fiscal Notes Are Prepared

A law or legislative rule and a written procedure for preparing fiscal notes can help ensure that comprehensive fiscal notes are prepared for all appropriate legislative proposals.

Ideally, to ensure that necessary information will be available, the preparation of fiscal notes that cover at least five years and perhaps longer when necessary should be required by law or legislative process rules. For example, Iowa General Assembly Joint Rule 17 requires that “A fiscal note shall be attached to any bill or joint resolution which reasonably could have an annual effect of at least one hundred thousand dollars or a combined total effect within five years after enactment of five hundred thousand dollars or more on the aggregate revenues, expenditures, or fiscal liability of the state or its subdivisions. . . . Each fiscal note shall state in dollars the estimated effect of the bill on the revenues, expenditures, and fiscal liability of the state or its subdivisions during the first five years after enactment.”[10]

In Texas: “The LBB [Legislative Budget Board] is directed by Section 314.001 of the Texas Government Code . . . to establish a system of fiscal notes identifying the probable impact of each bill or resolution that authorizes or requires the expenditure or diversion of any state funds for any purpose other than those provided for in the general appropriations bill. The statute requires that the fiscal impact be projected for the five-year period that begins on the effective date of the bill or resolution and shall state whether or not the impact will continue thereafter. The director of the LBB may choose to project the fiscal impact beyond the five-year period.”[11]

Florida Senate rules require: “(1) Upon being favorably reported by a committee, all general bills or joint resolutions affecting revenues, expenditures, or fiscal liabilities of state or local governments shall be accompanied by a fiscal note. Fiscal notes shall reflect the estimated increase or decrease in revenues or expenditures. The estimated economic impact, which calculates the present and future fiscal effects of the bill or joint resolution, must be considered. The fiscal note shall not express opinion relative to the merits of the measure, but may identify technical defects.”[12]

While all states except California and Hawaii have some statutory or legislative rule relating to fiscal notes, some are quite limited. Some states require fiscal notes only for bills relating to pensions or bills affecting businesses, for example, but may sometimes provide estimates for other types of legislation.

Links to each state’s statute or legislative rule covering fiscal notes may be found in Table 2 at the end of this report.

A Fiscal Note Does Its Work

A fiscal note provided at an appropriate point in the consideration of a legislative proposal can affect the shape of legislation. It can help legislators avoid approving an unaffordable bill, and potentially point to more affordable ways to accomplish their objective. Here is an example.

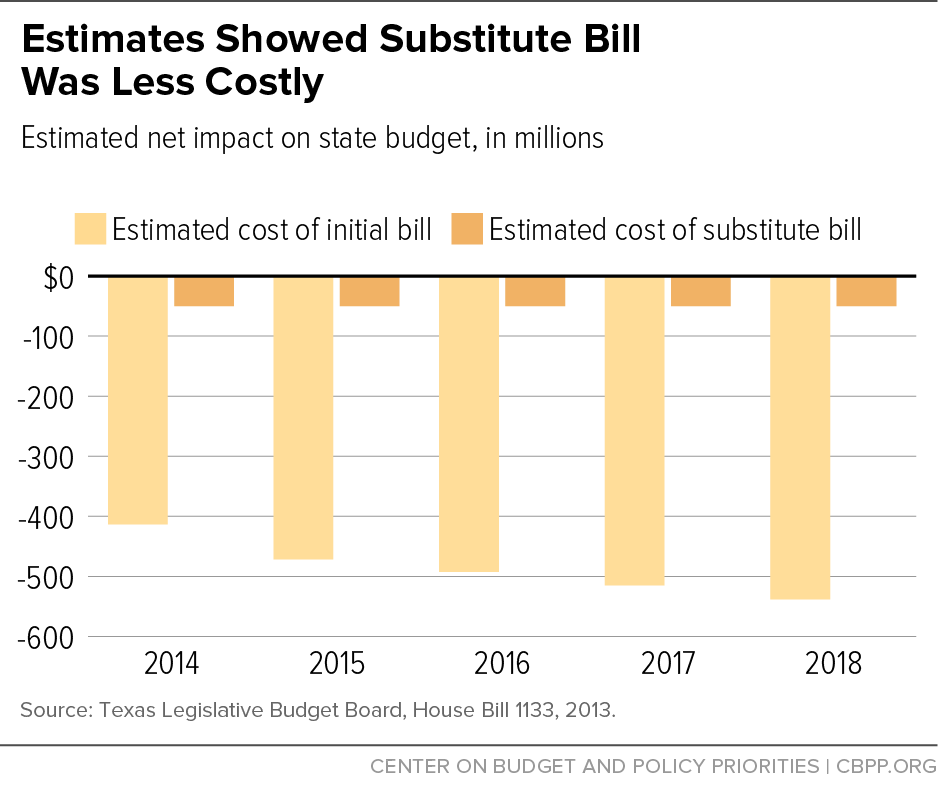

On April 9, 2013, the Texas Legislative Budget Board provided an estimate to the House Ways and Means Committee for HB1133, a bill that would provide a sales and use tax exemption for property used to provide cable television service, Internet access service, or telecommunications services. It found that the cost to the state general fund would be $413 million in the first year, rising to $538 million in the fifth year. In addition, by the fifth year, cities, transit authorities, counties, and special districts would lose a combined annual total of nearly $150 million.

The Ways and Means Committee apparently decided that was too costly, and submitted a substitute bill. The amended bill provided a tax refund rather than an exemption for property used for cable, Internet, or telecommunications, and further limited the amount of refunds that could be given in any calendar year to $50 million. So the cost to the state general fund would be a constant $50 million a year — about one-tenth as much as under the original bill — and there would be no cost to local governments.

Lawmakers ultimately enacted the legislation in its revised, less expensive form.

Fiscal Notes Can Show More Than State Budget Impacts

Some states include in their fiscal notes information that goes beyond the impact on the state budget. The additional information can give a fuller picture of proposed legislation’s consequences.

Impact on Local Government

In some states, fiscal notes consider the impact of legislation on local government finances where appropriate.

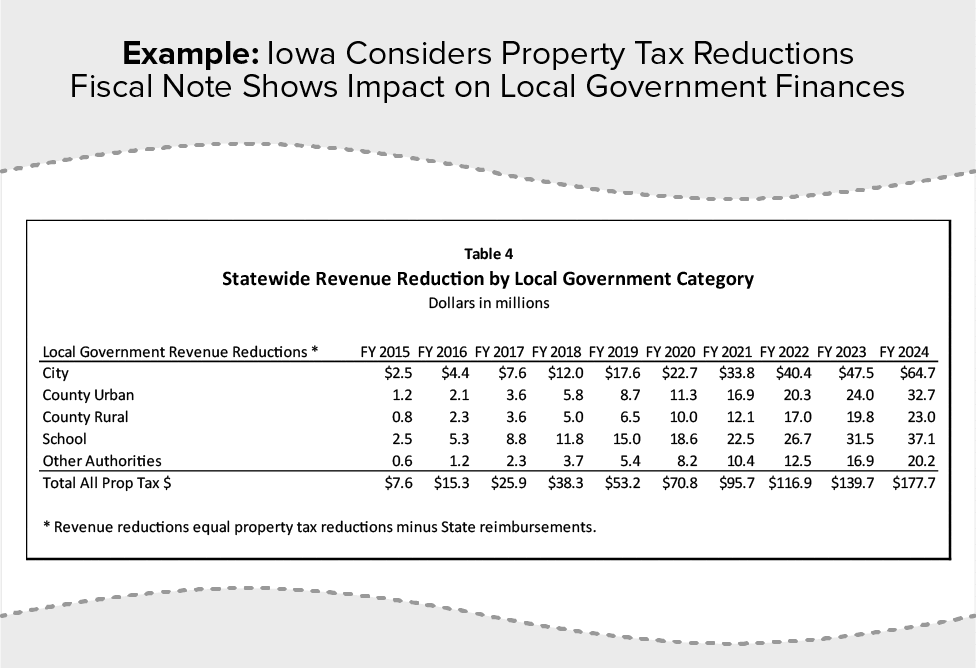

For example, legislation enacted in Iowa in 2013 made a number of changes to the property tax system, most of which reduced property tax collections. New state reimbursements or increases in school aid would offset some, but not all, of the losses to local government revenue. (The bill also included an income tax credit and an expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit, both of which affected only state funds.) A table in the fiscal note prepared as legislators were considering the bill showed the unreimbursed reductions in local government revenue by type of local government, projected for ten years. It also showed that the revenue loss to local governments would rise in each year over the decade, from $7.6 million in 2015 to $177.7 million in 2024.[13] (See Figure 9.) This type of information, added to the impact on the state budget, allowed legislators to fully consider the bill’s effects before passage.

Impact on Residents by Income Level

Whenever there is a change in taxation, the impact on individual state residents will vary. While fiscal notes cannot take individual impacts into account, they can measure the impact on groups of residents at different income levels.

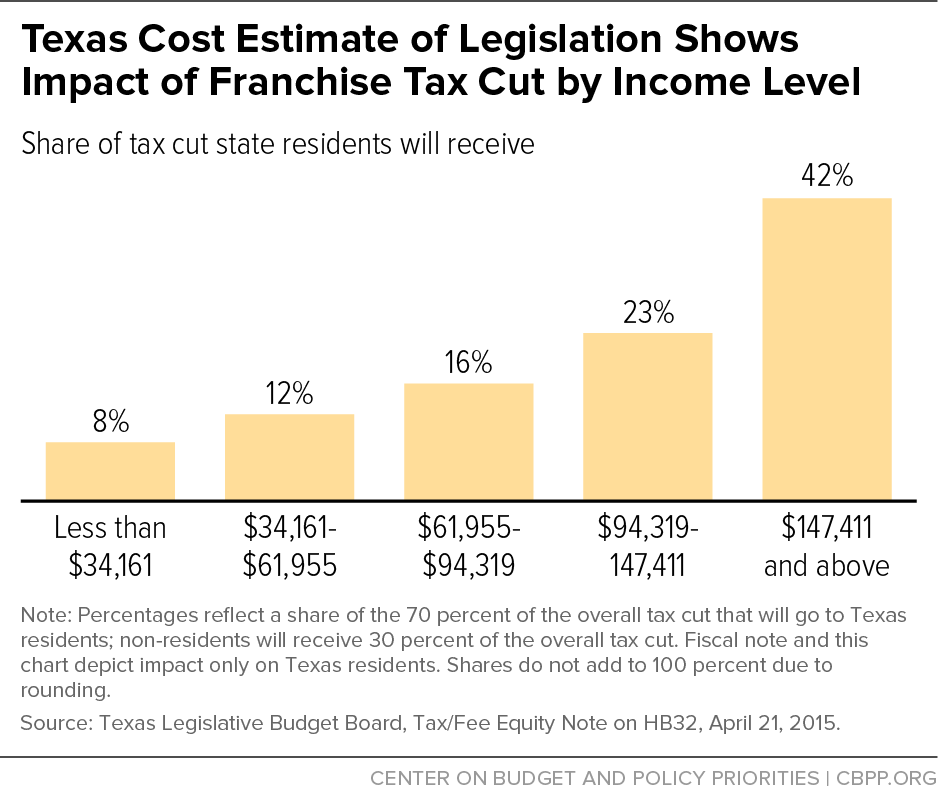

Texas does this for bills that make changes in taxes or fees. For example, a 2015 bill, ultimately enacted, proposed various cuts in the franchise tax (gross receipts business tax) rates. The fiscal note estimated the business tax reduction in 2017 at just under $1.3 billion. The fiscal note provided information on the impact on businesses by industry, as well as important information on the income distribution of the change. (See Figure 10.)

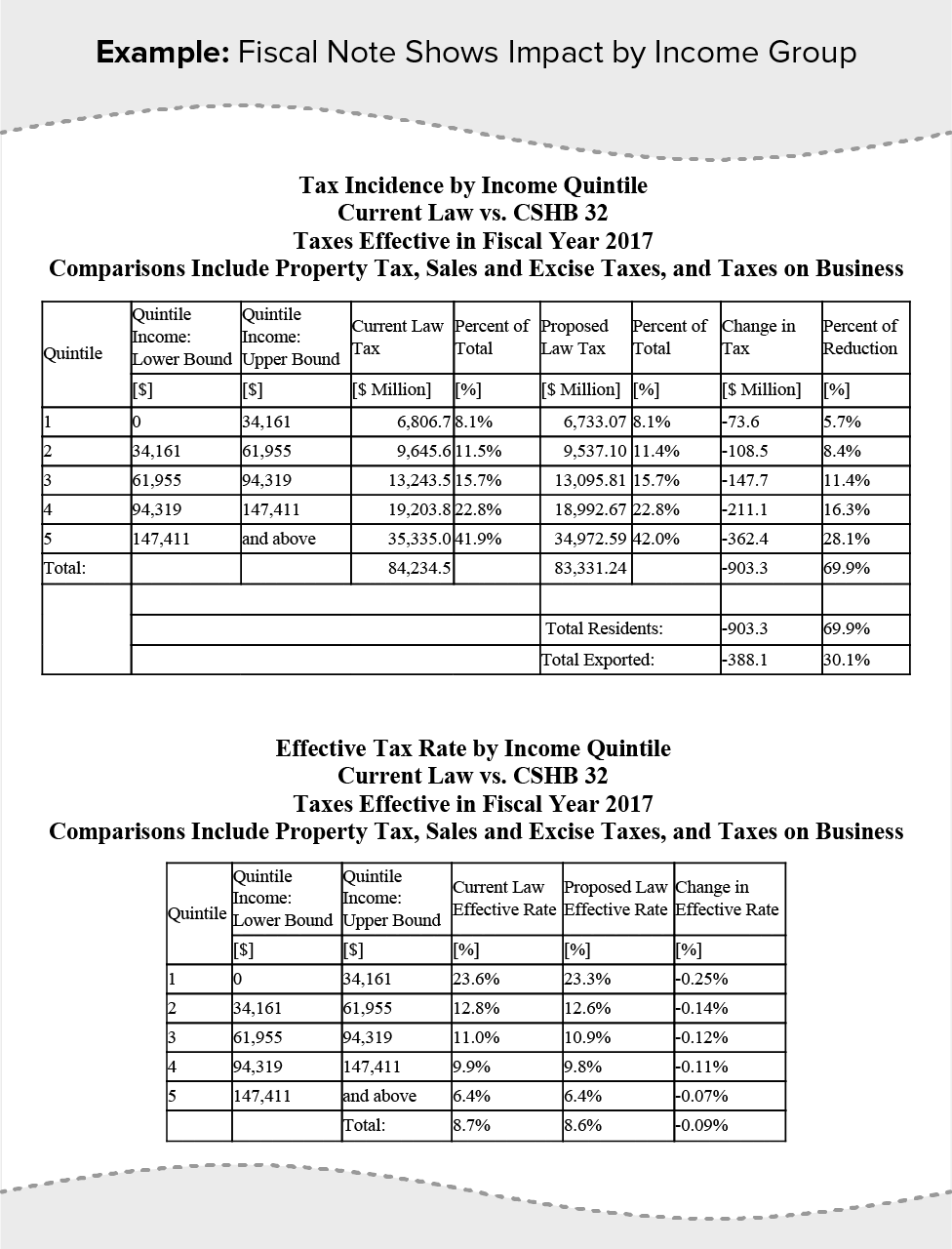

Texas is the only state that currently considers the incidence (final payer) of tax changes by income group and publishes that information in its fiscal notes. While in this case the tax cut will initially reduce taxes for businesses, some portion of that cut eventually will be passed on to consumers, employees, and/or investors.[14] The fiscal note finds that just over $900 million of the reduction would benefit households in the state. The lowest income quintile would receive 5.7 percent of the reduction, while the highest income quintile would receive 28.1 percent of the reduction. The fiscal note also shows the proposal’s impact on household effective tax rates, in this case measured as the tax change as a percent of the aggregate personal income, by income class.[15] (See Figure 11.)

Dynamic Scoring Is Flawed

Various states have experimented over the last 20 years, mostly unsuccessfully, with providing information about the assumed macroeconomic effects of proposed legislation. Attempting to quantify the extent to which a tax or spending change will affect employment, investment, and other economic variables and incorporating those results into the estimates of the budgetary impact of bills is called “dynamic scoring.” But dynamic scoring can be misleading if it is used as the official score.

All states incorporate some direct behavioral changes in their revenue estimates. For example, they may assume that an increase in a cigarette tax will reduce smoking. But it is a much further step to estimate indirect feedback effects from an impact on economic growth.

When considering indirect economic affects, there are many different models with a variety of assumptions and implications. As MIT professor Simon Johnson notes: “It is not exactly true that you can find a model that will support any claim, but this is sometimes uncomfortably close to the truth.”[16]

The results of dynamic scoring are affected by a model’s assumptions of how tax changes affect household and business decisions regarding how much to work, save, and invest. The range of results could be so great as to not be particularly useful to policymakers. For example, when the U.S. Congress’ Joint Tax Committee estimated the dynamic effects of a proposal to broaden the base of the federal personal and corporate income taxes and cut rates, it came up with eight different estimates — depending on the assumptions — ranging from additional annual revenue of between $5 billion and $70 billion.[17] Even in federal budget terms, that is a wide range that is not of much use to policymakers concerned about prudent fiscal policy.

Dynamic scoring is particularly inappropriate at the state level, because scoring uncertainty can wreak havoc in an environment of balanced budget requirements. For example, California experimented with dynamic analysis, adopting a requirement in 1994 and investing considerable resources in building a model and expert staff time in operating it. Among other things, it found that the “results were highly sensitive to the elasticities [responses] chosen for household migration, investment flows, and other factors for which there was often little consensus in the economics literature,” according to the former Director of Budget Overview and Fiscal Forecasting for the California Legislative Analyst’s Office.[18] The state allowed the requirement to sunset in 2000 and stopped producing the analyses.

California and most other states that have attempted dynamic analysis have found that the tax changes did not have much effect on economic growth.[19] In addition to California, Colorado and New Mexico tried dynamic analysis and found it to be “impractical and imprecise.”[20]

Indeed, G. William Hoagland, for many years a senior Republican congressional budget staff member, commented about the difficulty of constructing accurate dynamic models, saying, “Often, the economic literature is inconclusive about what those assumptions should be and thus, the resulting score can become increasingly subjective.”[21]

The experience of these states, and the issues relating to the varying models and lack of consensus in the economic literature, suggest that states should be wary of adopting dynamic scoring. Improving the quality of their current fiscal note processes is likely to be a better investment for many states. But states that nevertheless want to further experiment with dynamic scoring should acknowledge the inherent uncertainty of the results and should not rely on a dynamic score for purposes of budget planning or budget balancing.

Significant Room for Improvement

Most states regularly prepare and publish fiscal notes during the legislative process, but some states do not and some do so only for limited types of bills. Only one-quarter of the states project proposed legislation’s budgetary impact for at least four years into the future. Some states do not revise fiscal notes as the legislative process proceeds, and some do not make cost information publicly available. There is significant room for improvement to ensure that legislators have the information they need to make fiscally prudent decisions and the interested public has the information necessary to weigh in.

| TABLE 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State Fiscal Note Practices | ||||||

| Prepared For All or Substantially All Bills | Prepared by Nonpartisan Agency | Budget Impacts Shown for More Than One Year Consistently | Budget Impacts are Shown for at Least 4 Years | Revised During Legislative Process | Published on the Web | |

| Alabama | x | x | x | |||

| Alaska | x | x | ||||

| Arizona | x | x | x | |||

| Arkansas | x | x | ||||

| California | x | |||||

| Colorado | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Connecticut | x | x | x | x | ||

| Delaware | x | x | x | |||

| Florida | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Georgia | x | x | x | x | on request | |

| Hawaii | ||||||

| Idaho | x | x | x | |||

| Illinois | x | |||||

| Indiana | x | x | x | x | ||

| Iowa | x | x | x | x | on request | x |

| Kansas | x | x | ||||

| Kentucky | x | x | x | |||

| Louisiana | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Maine | x | x | x | |||

| Maryland | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Massachusetts | x | |||||

| Michigan | x | x | ||||

| Minnesota | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Mississippi | x | |||||

| Missouri | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Montana | x | x | x | on request | x | |

| Nebraska | x | x | x | x | ||

| Nevada | x | x | x | x | ||

| New Hampshire | x | x | x | |||

| New Jersey | x | x | x | x | x | |

| New Mexico | x | x | x | x | ||

| New York | ||||||

| North Carolina | x | x | x | x | x | |

| North Dakota | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Ohio | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Oklahoma | x | on request | x | |||

| Oregon | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Pennsylvania | x | |||||

| Rhode Island | x | x | x | x | ||

| South Carolina | x | x | x | x | x | |

| South Dakota | x | x | x | |||

| Tennessee | x | x | x | |||

| Texas | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Utah | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Vermont | x | x | x | x | ||

| Virginia | x | x | x | x | ||

| Washington | x | x | x | x | x | |

| West Virginia | x | x | x | |||

| Wisconsin | x | x | x | |||

| Wyoming | x | x | x | x | ||

| Total | 38 | 33 | 27 | 12 | 26 | 45 |

| District of Columbia | x | x | x | x | x | x |

Notes:

AZ – Prepares only on request of legislator, mostly for revenue bills

AR – Regularly prepares only for retirement bills, may do tax bills if requested.

CA – Rarely prepares fiscal notes

DE – Prepares for all expenditure bills, but prepares for tax bills only if they reduce revenue

HI – Never prepares fiscal notes

IL – Statute says that sponsor should request, but if he/she does not, another legislator may request if backed by the majority of Assembly or Senate

IN – Required by statute only for bills with impact on businesses, but Legislative Services Agency does fiscal note for all bills

KY – Prepares on request of sponsor for bills affecting the Commonwealth budget; but required for bills that affect local government budgets, pensions, corrections, or mandated health benefits.

MA – Prepares only for bills reported favorably from committee

MO – Beginning in 2015 fiscal notes prepared for measures that are phased in over multiple years will include the first three years of impact as well as an estimate of the cost in the first full year of implementation.

NY – Rarely prepares, but statute requires for pension bills

NC – Most bills get some form of fiscal analysis, but not always a formal fiscal note. Fiscal notes are required for legislation that affects the rate of incarceration or state employee retirement, disability, or health benefits

OK – Has a requirement but does not always prepare

PA – House and/or Senate appropriation committees prepare for bills that reach “third consideration” on the floor. SD – Prepares only when requested

VT – Statutory requirements vary with type of bill

WA – Prepares only for tax and fee legislation, not spending bills

a Arkansas lacks one, over-arching statute on fiscal notes. There are a number of different statutes that lay out fiscal note requirements based on the subject of the bill.

b Maine statutes require notes for changes in corrections and judicial policies.

c New York’s statute covers retirement bills only.

Improving State Revenue Forecasting: Best Practices for a More Trusted and Reliable Revenue Estimate

End Notes

[1] Although MS Code § 5-1-85 (2013) mandates that fiscal notes be published in electronic form on the Mississippi Legislature’s website, in practice this does not appear to happen. Similarly, Massachusetts Joint Rule 4A requires that the fiscal notes be made available on the official website of the General Court, but this does not appear to be followed in practice.

[2] These are California, Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New York, and Pennsylvania.

[3] Todd Haggerty and Erica Michel, “The Role of Fiscal Notes in the Legislative Process,” National Conference of State Legislatures, Legisbrief, Vol. 21, No. 48.

[4] Many states have a dollar threshold above which a fiscal note must be prepared.

[5] Beginning in 2015 in Missouri, fiscal notes prepared for measures that are phased in over multiple years will include the first three years of impact as well as an estimate of the cost in the first full year of implementation.

[6] Texas Legislative Budget Board, 2015 Fiscal Note, Texas House Bill 1250, http://www.legis.state.tx.us/tlodocs/84R/fiscalnotes/html/HB01250H.htm.

[7] The bill was reported out of the Ways and Means Committee after seeing the fiscal note, but the legislature adjourned for the year without further action on it.

[8] Maryland Department of Legislative Services, Fiscal and Policy Note, Revised, SB 167 2011 Regular Session, http://mlis.state.md.us/2011rs/billfile/sb0167.htm.

[9] Although MS Code § 5-1-85 (2013) mandates that fiscal notes be published in electronic form on the Mississippi Legislature website, in practice this does not appear to happen. Similarly, Massachusetts Joint Rule 4A requires that the fiscal notes be made available on the official website of the General Court, but this does not appear to be followed in practice.

[10] Iowa Legislative Services Agency, Fiscal Note Information Guide, June 2013, p. 1.

[11] Guide to Fiscal Notes: Instruction for Texas State Agencies, January 2013, p. 5.

[12] Florida Senate Rules and Manual, November 18, 2014, section 3.13.

[13] Fiscal note for SF 295 (2013), pp. 921-929, https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/lsaReports/graybook/archives/2013.pdf.

[14] There is controversy among economists over the proportion of business taxes that fall variously on consumers, employees, or investors, but it is accepted that business taxes are passed through in some proportions to these three groups. The Texas franchise tax is a gross receipts tax, which is generally thought to be passed to consumers in a manner similar to a retail sales tax.

[15] Texas Legislative Budget Board, Tax/Fee Equity Note on HB32, 84th Legislative Regular Session, April 21, 2015, http://www.legis.state.tx.us/tlodocs/84R/impactstmts/html/HB00032HD.htm.

[16] Simon Johnson, “Dynamic Scoring Forum: The Dangers of Dynamic Scoring,” TAXVOX, March 6, 2015.

[17] Joint Committee on Taxation, Macroeconomic Analysis of the “Tax Reform Act of 2014,” February 26, 2014, JCX-22-14.

[18] Brad Williams, “Dynamic Scoring Forum: California’s Dynamic Revenue Estimating Experience,” TAXVOX, March 2, 2015.

[19] Arizona JLBC Staff, “Dynamic Forecasting,” NCSL Budgets and Revenue Committee, November 29, 2007.

[20] Todd Haggerty and Erica Michel, “Count the Cost,” State Legislatures Magazine, July-August 2014.

[21] G. William Hoagland, “Dynamic Scoring Forum: Overblown Concerns?” TAXVOX, March 12, 2015. For an overview of the controversies in economic literature about how tax levels affect state economic growth, see Michael Mazerov, “Academic Literature Lacks Consensus on the Impact of State Tax Cuts on Economic Growth,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 17, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/academic-research-lacks-consensus-on-the-impact-of-state-tax-cuts-on-economic-growth; Michael Leachman and Michael Mazerov, “State Personal Income Tax Cuts: Still a Poor Strategy for Economic Growth,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 14, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-personal-income-tax-cuts-still-a-poor-strategy-for-economic.

More from the Authors