- Home

- Sequestration And Its Impact On Non-Defe...

Sequestration and Its Impact on Non-Defense Appropriations

The 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA) imposes tight limits on annual appropriations, first by creating caps that apply each year through 2021 and then by requiring additional reductions through a process known as sequestration. The law directed that the first year of this sequestration, 2013, would come through across-the-board cuts in most appropriated programs. Beginning in 2014, it directs that sequestration cuts would come by lowering the caps that would otherwise apply.

President Obama and Congress enacted measures that somewhat ameliorated the sequestration cuts in 2013, 2014, and 2015, but that relief expires in 2016 — raising concerns about the ramifications if policymakers cannot reach agreement on new legislation to alleviate future sequestration.

To be clear, the return of full sequestration does not mean a return to across-the-board cuts. Rather, sequestration will continue to come through reductions in the BCA-created caps.

Under full sequestration, the 2016 cap on non-defense appropriations is roughly at the 2015 enacted level for those appropriations, rising by just 0.2 percent. Thus, policymakers must offset any additional dollars that they appropriate for high-priority needs in 2016 by cuts elsewhere, and the purchasing power of non-defense programs will be eroded by inflation, population growth, and other costs. Indeed, just to keep pace with inflation since 2015, the 2016 cap on non-defense appropriations would need to be increased by $8.6 billion.

Nor is this just a one-year phenomenon. Instead, 2016 will be the sixth year of austerity in these programs. Non-defense appropriations have either fallen or remained essentially frozen in four of the last five years. In inflation-adjusted terms, the 2016 cap would be 17 percent below the 2010 level. Measured relative to the size of the economy, outlays on non-defense appropriated programs will likely equal the lowest level on record in at least five decades.

This paper describes the mechanisms that the BCA established, how policymakers subsequently modified those mechanisms, and the resulting effects on non-defense appropriations.

The BCA Caps

The BCA established legally binding caps on appropriations for each year from 2012 through 2021, with separate caps now set for defense and non-defense appropriations.[1] Non-defense appropriations constitute about one-sixth of the budget and support a wide variety of investments, services, and basic government functions. Examples include medical and scientific research, aid to education, veterans’ health care, national parks and environmental protection, housing assistance, public health, homeland security, law enforcement, and courts.

The starting point for the caps was the 2011 appropriations that policymakers enacted four months before the BCA, which cut non-defense funding $42 billion (8 percent) below the level for 2010.[2] The BCA caps imposed further reductions in 2012, but they were designed to rise slowly in later years. By the middle of the decade, the caps were scheduled to rise by about 2 percent per year — roughly enough to begin keeping up with projected inflation, though not enough to also cover population growth or other rising needs or to offset previous losses. Due to the initial reductions and slow growth, the caps produced substantial cumulative budget savings.[3]

By setting appropriations caps in advance, policymakers departed from the usual budget process under which the President and Congress set the totals and details of appropriations year by year, based on current needs and fiscal conditions. While unusual, their action was not unprecedented, since Presidents and Congresses enacted similar caps in 1990 and extended them in 1993 and 1997 before allowing them to expire in 2002. What was unprecedented about the BCA action, however, was that it established appropriations limits ten years into the future. Policymakers had set earlier caps for no more than five years at a time.

Sequestration and the “Supercommittee”

The BCA also established a joint House-Senate Select Committee on Deficit Reduction (or “supercommittee”) and directed it to recommend additional legislative measures to reduce deficits by a total of at least $1.2 trillion over ten years.[4]

Further, if the supercommittee failed to reach agreement, or Congress failed to enact its recommendations, or they fell short of $1.2 trillion, the BCA created a back-up process to achieve the desired deficit reduction. Known as sequestration, the process was designed to cut programs — largely appropriated programs — by nearly $1.0 trillion over nine years beginning in 2013. (See the box on this and the BCA’s other type of sequestration.) With estimated interest savings, the sequestration cuts would yield $1.2 trillion in total deficit reduction — the goal for the supercommittee. The BCA spread such sequestration cuts equally over nine years and divided them equally between defense and non-defense programs; thus, it would cut each category by $54.7 billion a year between 2013 and 2021.

The supercommittee did not reach agreement, so sequestration took effect. For 2013, the BCA specified that sequestration would come through uniform across-the-board cuts in the two categories — probably because policymakers expected the 2013 appropriations to be in place before the 2013 sequestration trigger date arrived. For 2014 and subsequent years, the sequestration for appropriated programs operates in advance, by reducing the BCA caps below the levels that would otherwise apply, thus leaving decisions about which programs to cut to the regular appropriations process.

This special “joint committee” sequestration applies to some entitlement or “mandatory” spending as well as appropriations. The law exempts many mandatory programs, however, including Social Security, veterans’ benefits, federal military and civilian retirement, Medicaid, SNAP, child nutrition, and Supplemental Security Income, and limits sequestration in Medicare to cuts of no more than 2 percent in payment rates for hospitals, physicians, insurance companies, and other providers. In 2016, the mandatory cuts total about $18 billion, or roughly one third of the total non-defense sequestration.

Sequestration Relief in 2013-2015

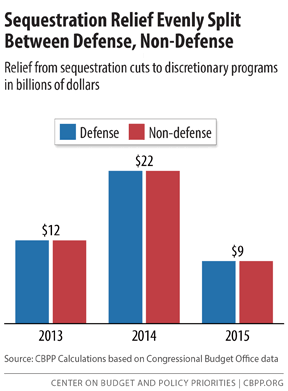

The President and Congress have provided relief from the full effects of sequestration in each year that it’s taken effect (see Figure 1). In each case, they gave the same amount of relief to the defense and non-defense categories, consistent with the 50-50 split of the sequestration cuts.

The American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA), which the President and Congress enacted in January 2013, provided relief from the 2013 sequestration. Often called the “fiscal cliff deal” because it also addressed the imminent end of the Bush-era tax cuts and extensions of unemployment benefits, ATRA reduced the sequestration for 2013 by $24 billion, evenly divided between defense and non-defense, and delayed its implementation from January 2 until March 1. The legislation offset half the cost of reducing sequestration by lowering the caps for 2013 and 2014, and offset the other half through changes in tax rules for individual retirement accounts.

The Bipartisan Budget Act, which policymakers enacted in December 2013, provided relief from sequestration in 2014 and 2015. Often called the “Murray-Ryan agreement,” after then-Senate and House Budget Committee Chairs Patty Murray and Paul Ryan, respectively, who led the negotiations, the measure reduced the required sequestration by $22 billion apiece for the defense and non-defense categories in 2014 and by $9 billion for each category in 2015. It offset the cost over ten years with savings in mandatory programs and user fees.[5]

The Murray-Ryan amelioration of sequestration covered only two years, however, and the full amount of sequestration that the BCA specified will return beginning in 2016 — unless policymakers take additional measures to further ameliorate it.

Effects on Overall Non-Defense Appropriations

Due to the BCA caps, sequestration, and the subsequent modifications to sequestration, non-defense appropriations have been almost flat since 2012 in actual dollar terms, apart from a sharp dip in 2013. The 2014 total is only about 1 percent larger than it was two years earlier, and the 2015 total is just 0.1 percent above the 2014 level.[6] That’s because, with the exception of 2013, the modified sequestration cuts have roughly been offset by scheduled increases in the underlying caps.

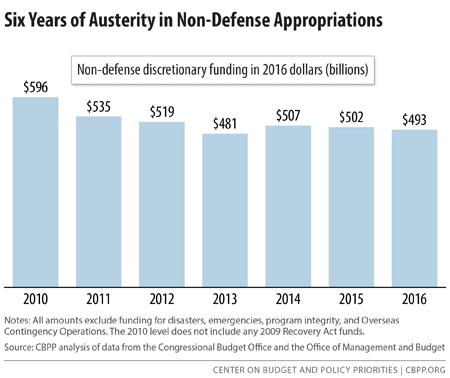

Funding totals that are stable or falling in actual dollar terms mean substantial real cuts when we consider the effects of inflation, as shown in Figure 2. Measured in constant 2016 dollars, the 2015 cap on non-defense appropriations is $94 billion, or 16 percent, below the comparable 2010 level.[7]

If policymakers do not further adjust sequestration, the 2016 cap will be $493.5 billion, which is only slightly above the 2015 cap — growing by just $1.1 billion (0.2 percent). That’s because the original (pre-sequestration) cap rises by $10 billion in 2016 but the sequestered amount rises by $8.9 billion, almost entirely due to the loss of the sequestration relief that the Murray-Ryan deal provided for 2015.[8] (See Table 1.)

As a result, 2016 will be yet another year in which any dollar increases for urgent needs or high-priority programs must be offset by cuts elsewhere. For example, with a virtually flat cap on non-defense appropriations, policymakers will need to offset rising costs of health care and other services for veterans (for which Congress has already enacted an increase through advance appropriations); and they would also need to offset the cost of doing things like reversing previous cuts in medical research, expanding early childhood education, or tightening border security. Even where programs do not fall in dollar terms, inflation will continue to erode the purchasing power of appropriations. Overall, the 2016 cap would be 17 percent below the comparable 2010 level after adjustment for inflation.

In 2017, the caps will start rising even with sequestration fully in place, because the underlying BCA caps rise while non-defense sequestration remains fairly constant in dollar terms. The increase will only roughly match the rate of inflation, however, with no adjustment for population growth or other needs. Thus, inflation-adjusted non-defense appropriations would finally stop falling, but will stabilize at levels greatly reduced from 2010.

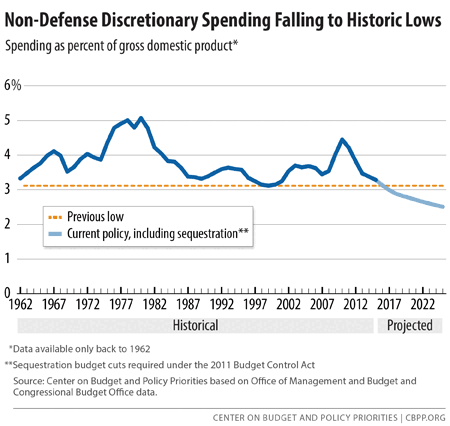

The decline is even sharper when we measure spending relative to gross domestic product (GDP) — a standard way of comparing spending over long periods. On this basis, outlays for non-defense discretionary programs have been shrinking steadily since 2010. Current Congressional Budget Office projections indicate that, under the caps and sequestration currently in place, outlays for these programs in 2016 will be 3.1 percent of GDP, equal to the lowest percentage on record (with data back to 1962). That percentage will continue to fall if the caps and sequestration remain unchanged, setting a new record low in 2017 and falling further after that. (See Figure 3.)

In short, the BCA, with its caps and sequestration, will soon mean that the federal government is devoting the lowest share of national income in at least five decades to the services and investments covered by non-defense appropriations.

Annual Caps on Non-Defense Appropriations (in billions) |

||||

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Change, 2015 to 2016 | |

| BCA Caps Before Sequestration | $506.0 | $520.0 | $530.0 | +$10.0 |

| Sequestration Cuts | -36.6 | -36.9 | -36.5 | +0.4 |

| Murray-Ryan Agreement | +22.4 | +9.2 | 0.0 | -9.2 |

| Resulting Caps | 491.8 | 492.4 | 493.5 | +1.1 |

| Note: Figures may not add to totals due to rounding. The BCA is the 2011 Budget Control Act, The Murray-Ryan budget agreement is the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013. Source: Office of Management and Budget |

||||

The BCA’s Two Different Types of Sequestration

The BCA actually establishes two different types of sequestration that could potentially apply to appropriations. One, which is the focus of this paper, produces additional budget cuts as a replacement for the deficit reduction that the supercommittee was supposed to achieve. The other enforces the appropriations caps. Because both types are often simply referred to as “sequestration,” confusion sometimes results.

In general, sequestration is a process established by law through which the executive branch reduces certain funding based on specified triggers and formulas. Policymakers have used it from time to time to enforce various budget limits, including deficit targets set by the 1985 Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act and appropriations caps and pay-as-you-go rules under the 1990 Budget Enforcement Act.

The first type of sequestration that the BCA established simply enforces the appropriations caps set by that law. Under this process, after Congress adjourns at the end of a session, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is required to evaluate the enacted appropriations to determine whether they comply with the caps. If it finds a violation, OMB must apply uniform percentage cuts to appropriations in the category where the overage occurred in order to eliminate it. With one very tiny exception, this type of sequestration has never been triggered. It won’t likely be triggered in the future either, since Congress won’t likely enact appropriations that exceed a cap knowing the result will be across-the-board cuts.

As discussed in this paper, the BCA also established a second type of sequestration, to produce additional spending cuts in the event that the supercommittee process failed. This sequestration process was triggered beginning in 2013 and remains in place. It operated through across-the-board cuts in 2013, making it superficially resemble the first type of sequestration — except that its purpose was to produce further spending cuts even though Congress had complied with the applicable appropriations caps. For 2014 and all subsequent years through 2021, this supercommittee-related sequestration operates by reducing the caps below the levels that the BCA set, as this paper explains. And if policymakers enacted appropriations that exceeded the reduced caps, the first type of sequestration would then also be triggered to eliminate the violation.

End notes:

[1] Initially, the caps applied to “security” and “non-security,” categories, but under the BCA (as amended by the American Taxpayer Relief Act) they shifted to “defense” and “non-defense” in 2014 as part of the sequestration process described in the next section. When the categories shifted, the dollar targets for those categories shifted as well. The “security” category is considerably broader than the “defense” category, mostly because (unlike defense) it includes the Department of Veterans Affairs, the International Affairs budget function, and all of the Department of Homeland Security.

[2] These figures are based on a comparison between the final enacted levels for fiscal years 2010 and 2011, excluding war and emergency funding. In addition to numerous cuts in appropriations, the reduction includes the effects of certain changes in mandatory programs in the appropriations legislation and increased receipts from mortgage insurance programs.

[3] See Richard Kogan and William Chen, “Projected Ten-Year Deficits Have Shrunk by Nearly $5 Trillion Since 2010, Mostly Due to Legislative Changes”, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 19, 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=4106.

[4] Technically, the BCA gave the joint committee a $1.5 trillion target for total deficit reduction. However, $1.2 trillion was the effective target because that was the amount needed to avoid the special sequestration, as described later in this section.

[5] The savings included extension of sequestration in mandatory programs for two more years, through 2023. For more information on the Murray-Ryan agreement, see Sharon Parrott, Richard Kogan, Joel Friedman, and Robert Greenstein, “Budget Deal Is Small in Scale and Falls Short in Some Ways, But Represents Modest Step Forward”, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 11, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=4061.

[6] These and other totals in this paper refer to appropriations subject to the BCA caps, and they do not include funding exempt from the caps (such as funding for overseas contingency operations, emergencies, disaster relief, and certain types of program integrity).

[7] Part of the reductions to meet the caps came through a decline in Census Bureau funding after the 2010 decennial census, increases in receipts from Federal Housing Administration mortgage insurance programs, and certain changes in mandatory programs. Excluding these factors, the inflation-adjusted cut in non-defense appropriations from 2010 to 2015 was 11 percent. On the other hand, even with these additional factors, if the levels were also adjusted to take into account population growth, then the reduction between 2010 and 2015 would have been 15 percent.

[8] The rest of the change in the amount sequestered from non-defense appropriated programs is the result of a small increase in the amount of sequestration from mandatory programs.

More from the Authors