- Home

- President’s Sequestration Relief Would E...

President’s Sequestration Relief Would Ease Austerity Without Raising Deficits

The President’s budget would provide relief from “sequestration” cuts to non-defense and defense appropriations in 2016 and future years to allow increased funding in areas such as education, scientific research, infrastructure, and national security. It would fully offset these restorations by alternate deficit reduction, consistent with the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA) and the sequestration relief enacted for previous years on a bipartisan basis. In fact, the President’s alternate deficit reduction measures would likely be more effective than sequestration in improving the long-term fiscal outlook.

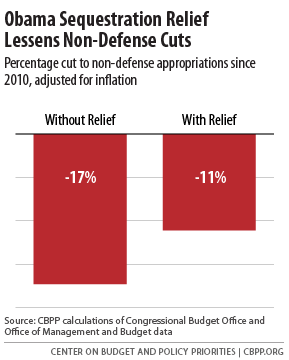

The BCA set caps on both defense and non-defense appropriations, and sequestration lowered those caps when Congress failed to enact the additional deficit reduction that the BCA mandated. The President’s proposal would shrink the sequestration cuts in 2016 by roughly equal amounts: $38 billion in defense and $37 billion in non-defense. This would eliminate the 2016 sequestration in non-defense programs. However, the non-defense cap would still be 11 percent below the 2010 level after adjusting for inflation (see Figure 1).

Sequestration Relief Is Consistent with BCA and Helps Reduce Long-Term Deficits

The President’s budget would scale back the sequestration cuts that the BCA imposed when policymakers failed to enact other deficit reduction. In addition to establishing caps on appropriations through 2021, the BCA created a joint House-Senate Committee on Deficit Reduction (often called the “supercommittee”) to recommend further steps to reduce deficits by at least $1.2 trillion over ten years. It also created a special sequestration process to be triggered if the joint committee did not reach agreement on the targeted amount of deficit reduction (or if Congress failed to enact its recommendations). That process was designed to produce $1.2 trillion in cumulative savings, mostly through further reductions in defense and non-defense appropriations.

Under the BCA, the first year of this sequestration, 2013, was implemented through across-the-board cuts in most appropriated (“discretionary”) programs. Beginning in 2014, the BCA implements sequestration on discretionary programs by lowering the defense and non-defense discretionary caps that would otherwise apply.

Policymakers have twice replaced part of the sequestration cuts with alternate deficit reduction. Most recently, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (referred to as the Murray-Ryan deal after the two principal negotiators) reduced both defense and non-defense sequestration in 2014 and 2015, offset with changes in mandatory programs and receipts.[1] That relief covered only two years, so sequestration will be fully in effect starting in 2016.

Like the Murray-Ryan deal, the President’s proposal ameliorates sequestration cuts that were never the desired outcome, but rather were a fallback in case policymakers failed to agree on an alternative. And, like Murray-Ryan, the President’s sequestration relief proposal is consistent with the original intent of the BCA, which envisioned restraining appropriations through caps and putting in place further deficit reduction through changes in mandatory spending and revenues.

Moreover, there is good reason to believe that the President’s approach would be more effective than sequestration in producing long-term deficit reduction. The offsets would be drawn from the array of entitlement and revenue changes proposed in the budget, which are mostly permanent measures that generate savings not just over ten years but in subsequent decades as well. In contrast, sequestration is a year-by-year process that ends after 2021.

Proposal Would Ameliorate, Not Eliminate, Appropriations Restraint

Under the President’s proposal for sequestration relief, funding for non-defense appropriations would still be tight, given the deep cuts in this budget area in recent years. If sequestration remained fully in place, the 2016 cap on non-defense appropriations would be about 17 percent below the comparable 2010 level, adjusted for inflation; under the President’s plan, the inflation-adjusted cut since 2010 would be 11 percent.

If one adjusts for population growth as well as inflation, the 2016 level without sequestration relief would be 21 percent below the comparable 2010 level, while the President’s proposed level would be 15 percent below 2010.

The President’s budget continues to provide sequestration relief in the years after 2016, but the amount of relief declines a bit from year to year, especially towards the end of the decade. The increases in the caps would not be sufficient to keep up with inflation in all years, and thus the purchasing power of appropriations would begin to decline again.

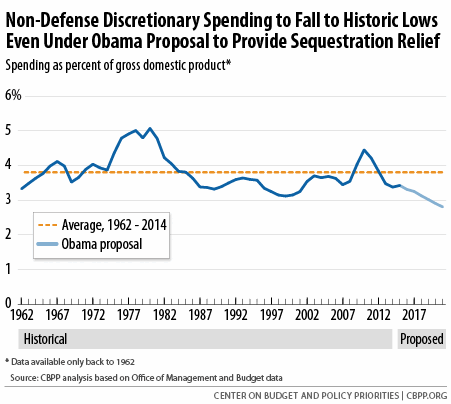

The level of austerity produced by the BCA becomes even clearer when one measures non-defense appropriated spending relative to the size of the economy, as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP).

Under the BCA caps and sequestration, non-defense discretionary spending fell from 4.4 percent of GDP to 3.3 percent between 2010 and 2015, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).[2] If full sequestration is imposed in 2016, CBO estimates that this share will drop to 3.1 percent of GDP, tying the lowest level on record in data that go back to 1962.

The President’s proposed sequestration relief would simply delay that outcome by a couple of years. Non-defense discretionary spending under the President’s budget would be 3.3 percent of GDP in 2016, the Office of Management and Budget estimates — a bit above the record low but well below the 3.8 percent average over the 1962-2014 period.[3] Even with the President’s proposed sequestration relief, that percentage would steadily fall; by 2018 it would equal the record low of 3.1 percent of GDP and by 2019 it would set a new record low. (See Figure 2.) As long as the basic BCA caps remain in place, non-defense discretionary spending will likely continue to fall as a share of the economy, with or without sequestration.

In sum, the President is not proposing an end to austerity in appropriated programs. Rather, he is simply proposing to ease that austerity somewhat in the near term. By doing so, the budget can recommend useful increases in areas ranging from medical research to job training to early childhood education.

Some Funding Increases Made Possible by Sequestration Relief

While it may not alter the longer-term trajectory of non-defense appropriations, the President’s proposal for sequestration relief makes significant additional resources available in 2016 for numerous priorities and needs, including regaining some of the ground lost over the past five years. Here are a few examples:

- Veterans’ benefits and services. The President proposes an overall increase of $5.1 billion (7.9 percent) in discretionary programs for the Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA), including increases of $4.2 billion for medical care, $582 million for major construction projects at DVA facilities, $166 million for processing claims for disability and other benefits, and $230 million for improved information technology.

- Job training and employment. The Labor Department budget includes an increase of $263 million (8.4 percent) for employment and training services, which were reauthorized last year on a bipartisan basis. Even with this increase, funding would still be 21 percent below the 2010 level after adjustment for inflation. The budget also includes an additional $500 million to support in-person employment services for unemployed workers.

- Medical research. The budget includes a $1 billion (3.3 percent) increase for the National Institutes of Health (NIH), including funding for initiatives in areas such as neuroscience and precision medicine along with other ongoing research. NIH funding declined by more than $600 million in nominal terms between 2010 and 2015, so this increase will restore past cuts and begin to make up for purchasing power lost through inflation. On an inflation-adjusted basis, the increase would still leave NIH 11 percent below the 2010 level. NIH estimates that the budget request will support approximately 1,241 more research grants in 2016 than in 2015, though this would still be considerably fewer grants than supported in 2010.

- Head Start. The budget includes a $1.5 billion (18 percent) increase for Head Start, including funding to ensure that all Head Start programs provide full-day and full-year services and to further expand access to high-quality early learning for infants and toddlers through Early Head Start and child care partnerships.

- Aid to education. The Education Department budget includes a $1 billion (6.9 percent) increase for “Title I” grants to local school districts serving low-income and disadvantaged communities. Funding for these grants declined in nominal terms between 2010 and 2015; the proposed increase will help make up for lost purchasing power in this program, which operates in 84 percent of the nation’s school districts and more than half of all public schools. After this increase, funding would still be 5.0 percent below 2010 on an inflation-adjusted basis.

- Housing assistance. The budget includes $512 million to restore 67,000 Housing Choice Vouchers lost due to sequestration since March 2013. Within this total, 30,000 vouchers would be targeted to homeless families, homeless veterans, survivors of domestic and dating violence, and families that need rental assistance to reunite with children in the foster care system.[4] This is part of a $1.8 billion increase in tenant-based rental assistance, with the remainder going to maintain and effectively administer in 2016 the vouchers currently in use.

- Homeland Security. The budget includes a $3 billion (7.9 percent) increase for the Department of Homeland Security, excluding disaster relief amounts exempt from the BCA caps. This includes increases of $800 million for customs and border protection, $923 million for immigration and customs enforcement, $200 million for pre-disaster mitigation grants through the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and $194 million for flood hazard mapping and risk analysis.

- Internal Revenue Service. The budget includes a $2 billion increase for the IRS to help reverse the drastic cuts in recent years and improve services to taxpayers as well as tax compliance efforts. Even with this 18 percent increase, 2016 funding would still be 5 percent below the 2010 level on an inflation-adjusted basis.

- Social Security operations. The President requests a $707 million (6 percent) increase in the operating budget of the Social Security Administration. The additional funds would begin reversing cuts in the number of hours that local offices are open, correct deterioration in services provided by telephone, reduce backlogs of pending hearings on disability benefits, and increase program integrity efforts, among other things.

- Scientific research. The budget includes increases of $379 million (5.2 percent) for the National Science Foundation and $272 million (5.4 percent) for science programs at the Department of Energy.

- Census. The budget includes an increase of $412 million for the Census Bureau, with the majority of that increase going to preparing for the 2020 decennial census, including designing and testing new tools and methods to reduce costs while maintaining and improving quality.

Appendix

Non-Defense Discretionary Funding (in billions of dollars) | ||||||||

Enacted | FY 2016 Budget Proposal | |||||||

2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

| BCA Caps Before Sequestration a | 506.0 | 520.0 | 530.0 | 541.0 | 553.0 | 566.0 | 578.0 | 590.0 |

| Sequestration Cuts | -36.6 | -36.9 | -36.5 | -36.9 | -36.9 | -36.0 | -35.1 | -34.2 |

| “Murray-Ryan” Sequestration Relief b | +22.4 | +9.2 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| BCA Caps After Sequestrationa | 491.8 | 492.4 | 493.5 | 504.1 | 516.1 | 530.0 | 542.9 | 555.8 |

| Proposed Sequestration Relief c | n.a. | n.a. | +36.5 | +36.9 | +34.9 | +30.0 | +22.1 | +20.2 |

| Resulting Caps | 491.8 | 492.4 | 530.0 | 541.0 | 551.0 | 560.0 | 565.0 | 576.0 |

| a BCA = Budget Control Act of 2011 b “Murray-Ryan” sequestration relief refers to the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013. c See FY 2016 Budget, Summary Table S-10. Source: Congressional Budget Office, Office of Management and Budget | ||||||||

End Notes

[1] The other enacted legislation that provided sequestration relief was the American Taxpayer Relief Act, which reduced the amount of sequestration required for 2013 and delayed its implementation for two months. The legislation offset half the cost by lowering the caps for 2013 and 2014 and the other half through changes in tax rules for individual retirement accounts.

[2] In order to be consistent with the long-term historical data, these estimates refer to total spending, including spending for categories such as overseas contingency operations and emergencies, which the BCA caps do not cover but the historical data do not present separately. These estimates refer to outlays (which sometimes lag appropriations) because that is the basis on which historical data are available for the longest time period.

[3] To maintain comparability with the historical data, the effects of the President’s proposal to move certain transportation spending from the discretionary to the mandatory side of the budget have been excluded from the estimate for the President’s budget used in this paragraph.

[4] See Barbara Sard, “Obama Budget Restores Lost Housing Vouchers,” Off the Charts blog, February 2, 2015, http://www.offthechartsblog.org/obama-budget-restores-lost-housing-vouchers/.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise