Some states may mistakenly believe that proposals to convert Medicaid into a block grant or otherwise cap federal funding would make their Medicaid costs more predictable and stable over time. In reality, a block grant is intended to provide predictability for the federal government by replacing the current financing system, under which the federal government pays a fixed share of a state’s Medicaid costs, with one in which the federal government would pay only a fixed dollar amount and leave the state responsible for all remaining costs. This is a radical change that would significantly shift both financial risks and costs to the states. [1]

If federal funding proved inadequate under a block grant or cap, states would have to contribute more of their own funds or else cut back Medicaid eligibility, benefits, and provider payments. That is an almost inevitable outcome, since federal policymakers who favor a block grant seek to use the conversion of Medicaid to a block grant to secure tens or hundreds of billions of dollars in savings for the federal government. The only way for a block grant to produce those savings is for it to provide states with far less federal funding than they would receive under the current system.

Moreover, under a block grant, federal funding would cease to rise automatically in response to a recession or unanticipated costs resulting from epidemics or medical breakthroughs that improve health or save lives but increase costs. When those developments occurred, states would have to bear 100 percent of the added costs.

Medicaid is jointly financed, with the federal government generally picking up between 50 percent and 75 percent of each state’s Medicaid costs (57 percent, on average) and the state responsible for the remainder. [2] Federal Medicaid financing is open-ended: if state Medicaid expenditures increase, the federal government shares in the increased costs; if state Medicaid expenditures decline, the federal government shares in the savings. Medicaid is the single largest source of federal funding for states.

Under proposals to convert Medicaid to a block grant or otherwise cap federal funding, the federal government would no longer pay a fixed percentage of states’ Medicaid costs. Instead, it would provide each state with a fixed dollar amount, with states responsible for all remaining Medicaid costs. Block-grant proposals vary on how this fixed amount would be determined, but typically a national Medicaid spending allotment would be set each year and a formula would determine each state’s share of that allotment. (Alternatively, each state could be given a capped amount of funding based on some specified calculation or formula, with the total grant amount nationally being the sum of the capped state allotments.) These national or state allotments would be adjusted annually in order to reflect factors like growth in population, economic growth, or inflation; based on past block grant proposals, such adjustments likely would be only partial adjustments.

Block grant proposals typically tie these financing changes to greater flexibility for states in designing their Medicaid programs, allowing them to override federal requirements related to eligibility and benefits. They also typically include a maintenance-of-effort (MOE) requirement that states continue to spend at least what they currently contribute to their Medicaid programs, with some annual adjustments to that MOE level.

If a Medicaid block grant or federal funding cap is intended to produce a specified amount of federal budgetary savings, it must give states less federal funding each year than they would receive under the current financing system. Proposals typically accomplish this by increasing annual federal payments at a slower rate than the current baseline growth rate for federal Medicaid spending, which reflects expected growth in enrollment and health care costs and the aging of the population. The current baseline growth rate is a bit more than 7 percent annually, according to Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates. [3]

For example, one recent proposal (by Representative Paul Ryan (R-WI) and Alice Rivlin of the Brookings Institution) could increase the block grant funding level by up to 1.5 to 2 percentage points less each year than projected cost growth, with the difference compounding over time and growing rapidly. This plan, which would block grant Medicaid starting in 2013, would reduce federal Medicaid funding to states by $180 billion just through 2020, compared to current law, according to CBO. The cuts in funding to states would grow substantially larger over time. [4]

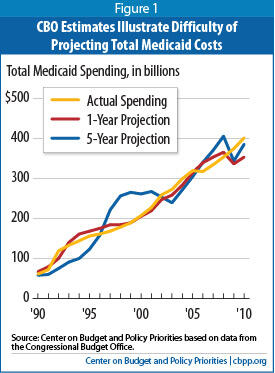

Moreover, the actual funding reductions under a block grant could turn out to be considerably larger than CBO’s official cost estimate would project. Health care costs are difficult to predict even a year or two in advance, and in a number of years, CBO projections have significantly overestimated or underestimated actual Medicaid costs (see Figure 1). Consider just the last three years:

- Total Medicaid costs in 2008 were approximately 13 percent lower than CBO had projected they would be in the estimate it issued five years earlier (in 2003), and 3 percent lower than CBO had projected just one year earlier, in 2007.

- In 2009, total Medicaid costs were 9 percent higher than CBO had projected five years earlier and 12 percent higher than CBO had projected in 2008.

- In 2010, total Medicaid costs were about 4 percent higher than CBO had projected five years earlier and 14 percent higher than CBO had projected in 2009, [5] likely because the recession turned out to be larger and deeper than had earlier been expected.

As discussed below, such differences often reflect unexpected increases in enrollment and/or per-beneficiary costs. Under a block grant, federal funding would no longer increase automatically to help cover these unanticipated costs.

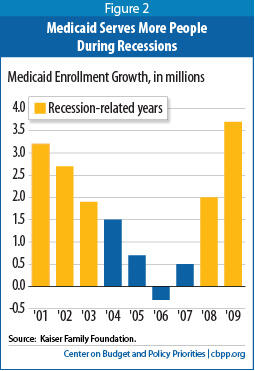

During a recession, when people lose their jobs and access to employer-sponsored insurance, many become eligible for and enroll in Medicaid. According to modeling by the Urban Institute, a one percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate results in a 1 million person increase in Medicaid enrollment among children and non-elderly adults. [6]

During the recent recession, Medicaid enrollment increased by nearly 6 million people (or 13.6 percent) between December 2007 and December 2009, according to the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. During the 2001 recession, Medicaid enrollment grew by a total of 7.8 million people (or 24 percent) between December 2000 and December 2003 (see Figure 2).

[7] Over the past 20 years — a period that includes three recessions — total Medicaid expenditures increased by 14 percent, on average, during recession years and in the first year after the official end of the recession (a period during which unemployment typically continues to rise), as compared to about 6 percent during other years. [8] (Overall spending rose much faster during recessions even though per-beneficiary spending grew more slowly in such years, likely the result of state cuts to provider rates and benefits to help address recession-induced budget deficits. [9] ) Under a block grant, states would have to pick up all of the recession-related costs of increased enrollment to the extent that those costs exceed the state’s federal funding cap.

Even under Medicaid’s current financing structure, states have had great difficulty absorbing the significantly higher Medicaid enrollment-related costs that have resulted from the current economic downturn, because those higher costs have coincided with plummeting state tax revenues and large budget shortfalls. (This has been true even though Congress temporarily increased the federal share of state Medicaid costs.) Recessions would pose dramatically greater risks to states under a block grant: their capped funding would be far less than the amount of funding they would receive under the existing financing system.

Developments in medical technology, changes in health care utilization patterns, and the onset of epidemics or new illnesses all can produce unexpected increases in medical costs. For example, prescription drug spending grew rapidly during the late 1990s and early 2000s throughout the U.S. health care system. In 1998 alone, national health spending on prescription drugs increased by 15 percent. Drug spending growth accounted for 40 percent of the increase in premiums for employer-sponsored insurance between 1998 and 1999. [10]

States experienced double-digit increases in their Medicaid prescription drug costs during this same period. Medicaid drug spending increased by an annual average of about 18 percent between 1997 and 2002. Prescription drugs were the fastest-growing Medicaid benefit by cost and spurred higher Medicaid cost growth overall. (This followed a period in which Medicaid spending growth had slowed due to the strong economic expansion, states’ expanded use of managed care for children and families, and the Medicaid savings in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.) [11] These substantial drug-cost increases both in Medicaid and throughout the U.S. health care system reflected several factors, including the availability of new “blockbuster” drugs, rising prices for existing drugs, and greater utilization by beneficiaries. [12]

Eventually, states were able to better control these costs by encouraging the use of generic drugs, instituting more robust utilization reviews, and establishing preferred drug lists. Moreover, drug manufacturers have marketed fewer new high-cost drugs in recent years and patents have lapsed on some popular drugs, allowing lower-cost generic versions to become available. Finally, with the establishment of the Medicare drug benefit in 2006, a portion of states’ drug costs for beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicare shifted to the federal government. Nevertheless, spending on prescription drugs illustrates how state Medicaid programs can experience unexpected growth in medical costs over a period of years.

State Medicaid programs also saw unexpected cost increases when the HIV/AIDS epidemic struck in the 1980s and early 1990s. In California, for example, the incidence of new HIV cases increased sharply between 1986 and 1996, with the number more than doubling over a 12-month span between 1992 and 1993.

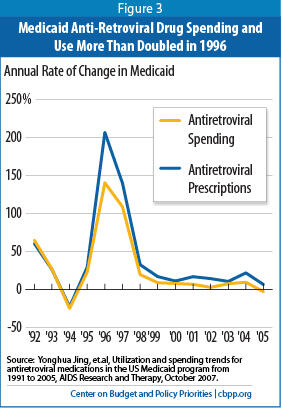

[13] Once more anti-retroviral medications became available to treat HIV/AIDS and the HIV drug cocktail began to be used in the mid-1990s, the number of anti-retroviral drug prescriptions covered by Medicaid programs nationwide jumped from about 170,000 in 1991 to nearly 2.2 million by 1999, with total annual Medicaid spending on these drugs rising from $31 million to $718 million over the same period. The number of prescriptions for anti-retroviral drugs and the level of Medicaid expenditures on those drugs more than doubled in a single year, 1996 (see Figure 3). And by 2005, state Medicaid programs were covering 3 million anti-retroviral prescriptions at a cost of nearly $1.6 billion.

[14] If a new treatment becomes available that is both more costly and more effective in treating a condition like HIV/AIDS, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or a particular cancer, that will significantly increase Medicaid costs both in a single year and over the long term. These technological developments save lives and improve health but can sharply increase average Medicaid costs on a per-beneficiary basis. Federal block grant funding would fail to respond to such developments. States would likely end up bearing all of the costs of covering these new treatments.

Congress has considered proposals to convert Medicaid to a block grant several times in the past. Retrospective analysis clearly shows that these proposals would have put states at a significant disadvantage compared to the current financing structure, especially during recessions.

An analysis that compared the federal funding states would have received under two block grant proposals — one that President Reagan supported in 1981 and one that Congress passed in 1995 but President Clinton vetoed — to the funding that states actually received found the following:

- Under the 1981 block grant plan, states would have received an estimated $77 billion less over the ten years from 1982 through 1991 than the amount they actually received. The largest reductions would have occurred in 1991 in the midst of a recession, when states would have received $28 billion (or 53 percent) less in federal Medicaid funds in a single year than the amount they actually received.

Under the Affordable Care Act, state Medicaid programs will be required to cover all non-elderly individuals up to 133 percent of the poverty line ($24,700 for a family of three) starting in 2014. The federal government will pick up the vast majority of the costs of this coverage expansion — 96 percent of those costs through 2019, according to CBO estimates (and no less than 90 percent in 2020 and thereafter). As a result of this expansion, CBO expects that by 2019, some 16 million more people will be enrolled in Medicaid than would have been the case under prior law but that state costs will be only 1.25 percent higher than they would be in the absence of health reform. The Medicaid expansion is one of the main reasons that CBO expects the Affordable Care Act to reduce the number of uninsured people by an estimated 32 million by 2019.

Because block-grant proposals typically give states much greater flexibility regarding Medicaid eligibility, it is difficult to see how states could still be required to institute the Medicaid expansion. If the Medicaid expansion continued to be required, the federal government would effectively pay for substantially less of the cost of the Medicaid expansion, because overall federal Medicaid funding would be substantially lower under a block grant than under the current funding structure. This would result in the Medicaid expansion being substantially more costly for states over time if it remained in place.

- Under the 1995 block grant plan, [15] states would have received more federal funds over the first four years than under the existing financing structure because actual Medicaid expenditures between 1996 and 1999 turned out to be lower than projected (for the reasons noted on the previous page). Once the recession started in 2001, however, states would have faced sizable reductions. Federal block grant funding would have been an estimated $3 billion (3 percent) lower in 2000, $10 billion (8 percent) lower in 2001, and $23.3 billion (16 percent) lower in 2002 than the federal funds that states actually received. Those reductions would have more than offset the funding gains over the first four years, resulting in a net reduction of $18.5 billion over seven years. [16]

In 2003, President Bush proposed a Medicaid block grant that, unlike the 1981 and 1995 proposals, was intended to be budget-neutral, with states receiving capped federal funding intended to approximate what they were projected to receive over the next ten years (2004-2013) under the current financing structure. [17] The Bush Administration never explicitly defined what the annual growth rate would be or how state-specific allotments would be calculated, making modeling of its effects difficult. As noted above, however, any Medicaid block grant proposal considered in 2011 will almost certainly be designed to achieve substantial federal savings by setting the block grant amounts at levels well below what states are projected to receive under the current structure. Moreover, even under the 2003 block grant, states would still have been at high risk of inadequate federal funding due to higher-than-projected costs related to recessions (including the current one) and unanticipated medical cost growth. [18]

Some states may believe they can make up for reduced federal funding under a block grant by exercising the greater flexibility that block grant proposals typically give them to make their programs more cost-effective, without unduly cutting eligibility, benefits, or provider payments. Such hopes would likely prove unrealistic:

- States already have considerable flexibility over Medicaid spending. A significant majority of state Medicaid spending is already “optional” — that is, it involves the coverage of populations and/or the provision of benefits that federal law does not require states to provide. [19] In addition, states already have significant control over reimbursement rates for providers. During the current state budget crisis, nearly all states have used this flexibility to scale back their Medicaid programs, particularly in provider reimbursements but also in benefits. [20] States made similar cuts in the last recession, including eliminating coverage for between 1.2 million and 1.6 million low-income individuals before the federal government provided added financial support. [21]

- The funding reductions under a block grant would likely be so large as to require substantial cuts. Compensating for the magnitude of the federal funding reductions resulting from a block grant — like the $180 billion in reductions through 2020 under the Ryan-Rivlin proposal — would be impossible without deep cuts both to Medicaid beneficiaries and to the providers and managed care plans that serve them. Moreover, these cuts would likely be deepest at times when individuals and families most need Medicaid, such as during a recession when states will also be facing large revenue declines and thus unable to contribute more state funding.

- The ensuing cuts would likely be injurious for tens of millions of low-income children, parents, pregnant women, seniors, and people with disabilities. States, for example, might be given flexibility to cap Medicaid enrollment — under current law, all eligible individuals who apply must be allowed to enroll — which would leave uninsured a substantial number of people whose low incomes would otherwise qualify them for Medicaid. Many current beneficiaries could also be made ineligible and end up uninsured as states significantly curtail coverage.

In addition, Medicaid provides certain benefits not typically offered by private insurance that are tailored to meet the needs of especially vulnerable beneficiaries — particularly people with severe disabilities — who have traditionally been excluded from the private insurance market. Such services, including case management, therapy services, and mental health care, are critical for impoverished people with serious disabilities but are expensive. States faced with funding limits under a block grant would likely have no choice but to curtail them.

Children could lose access to EPSDT (Early Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment), a comprehensive pediatric benefit designed to ensure that low-income children receive preventive medical screening and treatment for health problems they are found to have. Private insurance typically does not provide such comprehensive pediatric coverage. This broader coverage is critical for poor children, particularly those with special health care needs, who often go without preventive care and advanced medical treatments that they need if their insurance doesn’t cover those services, because their parents can’t afford to pay for the services.

Medicaid also ensures that coverage is affordable by generally not charging premiums and requiring only modest co-payments; research has found that premiums and cost-sharing tend to disproportionately lead poor households to forgo needed care or remain uninsured. Under a block grant, states could begin charging premiums that discourage enrollment (and leave people uninsured) and requiring burdensome deductibles and co-payments that reduce access to needed health care.

Seniors and people with disabilities would be at particular risk. They constitute one-quarter of Medicaid beneficiaries but account for two-thirds of all Medicaid spending because of their greater health care needs and because Medicaid is the primary funder of long-term care services, particularly nursing home care. Capping federal Medicaid funding would place significant financial pressure on states to scale back coverage for low-income seniors and people with disabilities in spite of their greater health needs.

A block grant could also allow states to shift beneficiaries into private insurance, offering them a voucher to purchase coverage on their own. Since Medicaid costs substantially less per beneficiary than private insurance, on average (largely due to its lower provider reimbursement rates and lower administrative costs), [22] shifting beneficiaries into private insurance would raise states’ costs, unless the vouchers purchased considerably less coverage than Medicaid provides. Because the block grant would provide less federal funding and private insurance costs substantially more per beneficiary, a voucher system for Medicaid enrollees would be viable only if it covered significantly fewer beneficiaries (leaving more people uninsured) or left many of those who received a voucher underinsured (i.e., without coverage for certain important health care services or facing premiums, deductibles, or co-payments they could have great difficulty affording).

States facing inadequate block grant funding would also likely have to further scale back provider rates. These rate reductions likely would apply not only to hospitals, nursing homes, physicians, and pharmacies in Medicaid fee-for-service but also to managed care plans that currently serve low-income children and their parents. That, in turn, could cause some providers and plans to withdraw from Medicaid, threatening beneficiaries’ access to needed care, particularly in communities — such as rural areas — that already are underserved. It also would place greater pressure on providers such as community health care centers and safety-net hospitals, which rely on Medicaid funding but which would face increased patient needs because of increases in the numbers of uninsured individuals if Medicaid enrollment were capped and eligibility restricted under a block grant.

Converting Medicaid to a block grant is attractive to some federal policymakers because it could produce large federal budgetary savings (and, in doing so, potentially ease pressure on certain other parts of the federal budget — such as the tax code, where, for example, policymakers will face a decision on whether to extend the Bush tax cuts for high-income households beyond 2012). But a block grant would almost certainly shift substantial costs to the states. Instead of the federal government picking up half to three-quarters of unanticipated Medicaid cost increases that result from a recession, the onset of a new disease, or the development of new pharmaceutical or other treatments, states would have to bear all of those costs themselves (once they exhausted their block grant allocation). A block grant would make Medicaid much more financially unpredictable and risky for states.

A block grant may also appeal to some federal policymakers because it would force the states to “be the bad guys” — making the decisions about which people to drop from coverage or which medical services to curtail when federal funding proved inadequate. States would essentially be left “holding the bag” — they would either have to contribute more state funding (by raising taxes or cutting other programs) or, more likely, exercise their increased flexibility to institute wide-ranging cuts in eligibility, benefits, and/or provider reimbursement rates. Those cuts could add millions to the ranks of uninsured. They also could impede access to care for tens of millions of people who continued being covered, as a consequence of substantial increases in co-payment and premium charges or cuts in reimbursements that cause substantial numbers of providers to leave the program.

A block grant would also significantly deepen state budget holes in recessions, forcing still larger state budget cuts or tax increases in those periods and thereby further slowing state economies and making the loss of jobs even greater.