- Home

- House Bill’s Deep Cuts In Public Housing...

House Bill’s Deep Cuts in Public Housing Would Raise Future Federal Costs and Harm Vulnerable Low-Income Families

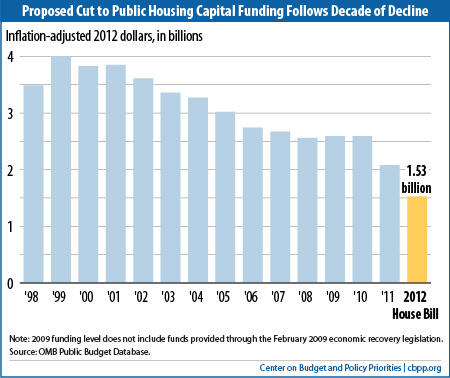

A House Appropriations subcommittee last week voted to reduce funding for public housing in 2012 by $1.4 billion, or 20 percent, below the 2011 level. This reduction, which would come on top of significant reductions in public housing capital funding over the past decade, would expose low-income households in public housing to deteriorating living conditions, increased risk of safety hazards, and possibly displacement from their homes. It also would likely raise future federal costs by putting off modest repairs (such as fixing leaking roofs) that would avoid more costly damage down the road, deferring energy efficiency improvements, and increasing borrowing costs for bonds used to finance public housing renovation.

The Budget Control Act enacted in August 2011 requires a reduction of about 5 percent in overall 2012 non-security discretionary funding. Appropriators could implement that reduction, however, in a manner that protects basic assistance to the nation's poor. The House subcommittee bill takes the opposite approach with respect to public housing, imposing disproportionately large cuts in a program that serves some of the nation's most vulnerable families and individuals. The public housing cuts also contradict the House subcommittee's stated commitment to protect funding for families currently receiving rental assistance. As the 2012 appropriations process advances, Congress should place a high priority on easing or eliminating these cuts.

Bill Would Sharply Reduce Funds to Repair and Renovate Public Housing

Public housing provides affordable homes to 1.1 million low-income households, the great majority of which consist of working poor families, elderly people, or people with disabilities. Two main federal funding streams support public housing developments: the public housing operating fund, which covers the gap between an agency's day-to-day operating costs and the rent that low-income residents can afford (generally residents are expected to pay 30 percent of income for rent), and the public housing capital fund, which covers substantial repairs and needed renovations.

As the chart shows, the capital fund cut follows a $440 million reduction in 2011 and a decade of steady funding erosion. If enacted, the House subcommittee bill would reduce funding to just 40 percent of the 2001 level in inflation-adjusted terms. This amount would cover less than half of the $3.4 billion in new repair and renovation needs that accumulate in public housing each year, according to a recent HUD-sponsored assessment. It also would fail entirely to address the program's estimated $26 billion backlog of unmet repair and renovation needs.

The House bill would reduce resources for public housing repair and renovation not just through its capital fund cut, but also through its operating fund cut. The operating fund level in the bill would provide $1.1 billion less than HUD estimates agencies will be eligible for under the operating subsidy formula, which is based on operating costs for comparable privately owned units.

The bill permits HUD to target this funding reduction on agencies that have accumulated reserves by operating their developments at a cost below their subsidy level. This policy could avoid forcing major cutbacks in day-to-day operating expenditures (such as security personnel or maintenance). But many agencies built up their reserves in order to fund essential renovations that would reduce the large backlog of unmet capital needs. Cutting funds for agencies with reserves — the likely outcome if the House level is enacted — would effectively compel them to cancel their renovation plans and use the funds to fill gaps in their operating budgets.[1]

Cuts Would Have Costly and Harmful Consequences

The House bill's reductions in resources for renovation and repair of public housing developments would have a series of adverse consequences.

- Deteriorating living conditions and increased risk of safety hazards for residents. Reductions in capital funding would make it even harder for housing agencies to take measures needed to maintain quality of life for vulnerable low-income residents (such as replacing aging plumbing and heating systems) or to avoid severe safety hazards (such as repairing security systems, sprinklers, or stair railings).

- Added federal costs in the future. If funding cuts compel an agency to defer a needed repair — fixing a leaking roof, for example — this could cause damage that would be more costly to fix later. In addition, federal utility subsidy costs will be higher if agencies must put off needed efficiency improvements. The recent HUD-sponsored capital needs assessment estimated that public housing developments require $4 billion in energy and water efficiency improvements, counting only improvements that would pay for themselves within 12 years.

Furthermore, deep cuts would make it more costly for agencies to issue bonds or take out loans backed by their future public housing capital fund grants. Agencies are permitted to borrow in this manner to enable them to undertake major capital projects that cost more than the agency receives in single year. But if Congress repeatedly cuts capital funds, lenders will view such bonds and loans as riskier investments and charge higher interest rates, further increasing the cost of addressing public housing capital needs. Moody's Investors Service predicted that an earlier proposal to cut the 2011 capital fund appropriation to a level just $100 million below the level in the current House bill would have led to major downgrades "of one to seven or more notches" in credit ratings for capital fund bonds. - Loss of construction jobs. According to reports submitted by local agencies, $4.0 billion in supplemental public housing capital funds provided through the Recovery Act have supported approximately 24,000 jobs through June 2011. This suggests that lowering capital funding by $510 million could eliminate or prevent creation of several thousand jobs in the hard-hit residential construction sector.

- Increased risk of neighborhood blight. If the exteriors of public housing developments deteriorate, this can lead to blight that lowers property values in surrounding neighborhoods. Many of the neighborhoods where public housing is located are already struggling with large numbers of foreclosed, vacant houses.

- Decline in the number of units available to families on waiting lists. Some units where needed repairs are left undone will become unlivable, compelling local agencies to leave the units vacant rather than offering them to low-income families on waiting lists for assistance. The loss of these units would be particularly unfortunate given that poverty and unemployment have increased significantly in the past few years and most communities have long public housing waiting lists.

- Loss of entire housing developments. If repairs to public housing continue to be deferred, some entire developments will ultimately become uninhabitable. This would force agencies to demolish or sell the developments, displacing families from their homes, eliminating needed affordable housing, and squandering decades of federal and local investment. Already, more than 165,000 public housing units have been demolished or otherwise lost since 1995 without being replaced with new public housing.

Reduction Deviates from Key Principles That Should Guide Funding Decisions

The Budget Control Act limits overall fiscal year 2012 funding for non-security discretionary programs — a part of the budget that includes most low-income housing programs — to a level about 5 percent below the 2011 level. This limit will compel congressional appropriators to make difficult decisions about which programs to cut. One principle that could help guide these decisions is that Congress should not place the burden of deficit reduction on vulnerable low-income people. This principle was set forth, for example, in the report of the recent fiscal commission chaired by Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson. The House bill's proposed cuts to public housing conflict with this principle, since they disproportionately reduce funds for a program that serves some of the nation's most vulnerable people.

In addition, in allocating reductions among housing and community development programs, Congress should place a higher priority on protecting funding for existing rental assistance than on funding construction of new affordable housing or extending rental assistance to additional families. This approach avoids the risk that families currently receiving rental assistance will be displaced from their homes. Also, maintaining existing public housing and other subsidized housing developments is generally more cost-effective than building new developments.

The House subcommittee acknowledged the importance of this principle, noting in a press release accompanying the 2012 Transportation-HUD funding bill that one of its priorities was to "preserve the funding for every person and family currently receiving an assisted housing benefit." The bill deviates from this goal, however, by cutting deeply public housing operating and capital subsidies, both of which are essential to maintaining existing public housing developments in livable condition.

Moreover, the bill cuts existing rental assistance while providing substantial funds for new construction in other programs that serve similar populations. For example, it provides approximately $240 million for development of new housing for the elderly under HUD's Section 202 program. Because of the high cost of new housing, this would build only about 1,400 units. By comparison, the same amount would fully address estimated capital needs in more than 10,000 public housing units — and more than 3,000 of those units would house elderly people if the funds were allocated proportionately to the 31 percent of public housing units with one or more elderly residents. Development of new units under Section 202 to serve the nation's growing low-income elderly population is important, but Congress should fund such new units only after making the more cost-effective investments required to sustain existing public housing assistance for seniors and other vulnerable families.

Congress Should Restore Funding and Take Other Measures to Support Public Housing

As the 2012 appropriations process advances, Congress should place a high priority on easing the public housing funding cuts in the House bill. Congress should restore public housing capital funding to the 2011 level and should seek to provide a more adequate level of operating funding to avoid draining reserves set aside for needed capital repairs or renovations.

Full restoration of the House bill's cuts would not address the $26 billion backlog of public housing capital needs — it would only limit the growth of the backlog — so additional measures ultimately would be needed. As an immediate step, Congress should include HUD's proposed Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) in appropriations legislation. RAD would enable HUD to convert funding for some public housing developments to project-based Section 8 subsidies. These subsidies would provide more reliable funding and make it easier for agencies to borrow private funds to rehabilitate public housing developments.

End Notes

[1] Use of public housing operating reserves to supplement capital budgets is a longstanding practice. A recent HUD policy decision, however, interpreted ambiguous statutory language to prohibit expenditure of operating subsidies (including reserves) for substantial renovation, with only limited exceptions. For agencies to have flexibility to use the reserves for a broad range of needed renovation projects, Congress or HUD would need to reverse this decision; that could be done in the fiscal year 2012 appropriations bill if Congress elected to do so.

[2] For addition information on the RAD proposal, see Will Fischer, "Converting Funding of Some Public Housing Subsidies to Section 8 Subsidies Would Help Preserve Needed Units," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 25, 2011. A letter from a range of housing organizations supporting enactment of RAD is available at http://www.clpha.org.