Medicaid Expansion Is Producing Large Gains in Health Coverage and Saving States Money

End Notes

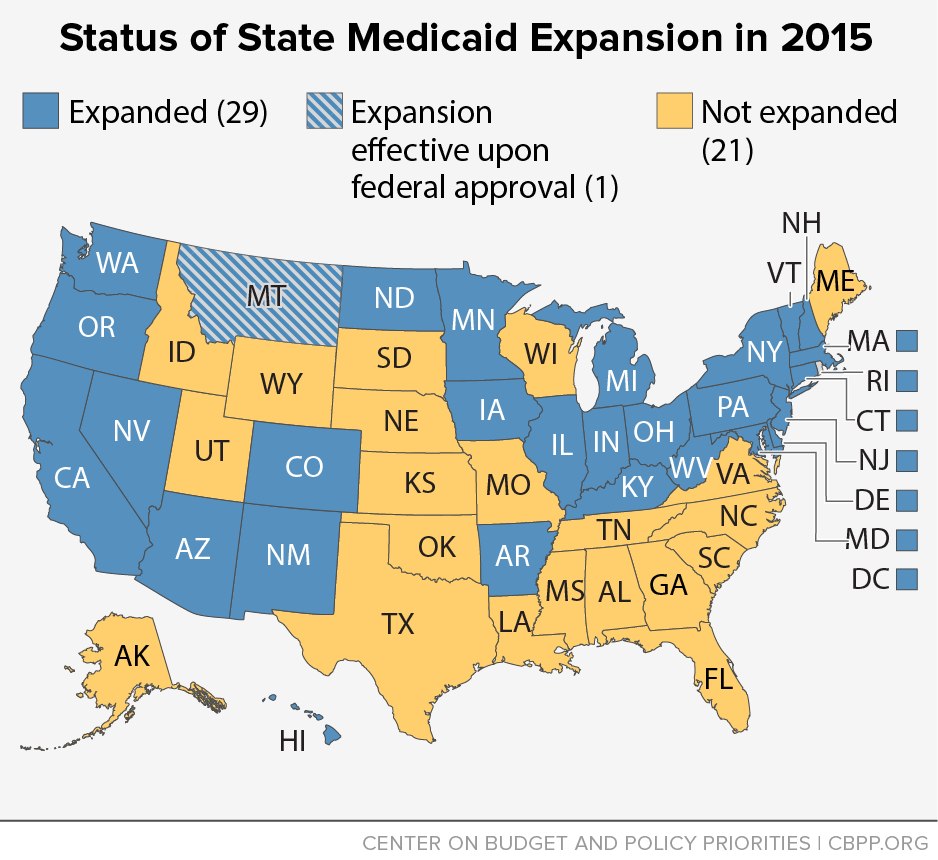

[1] Twenty-eight states and the District of Columbia have implemented the Medicaid expansion. This does not include Montana, where the legislature approved a Medicaid expansion on April 18, contingent upon the state gaining federal approval for a waiver.

[2] Jenna Levy, “In U.S., Uninsured Rate Dips to 11.9% in First Quarter,” Gallup, April 13, 2015, http://www.gallup.com/poll/182348/uninsured-rate-dips-first-quarter.aspx.

[3] Like the Gallup and Healthways survey, one government survey and three additional independent surveys all show a significant reduction in the share of non-elderly adults without health insurance coverage since the major coverage provisions of the ACA took effect in 2014. Results vary slightly due both to differences in survey methodology and the period of time captured. These surveys — from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Urban Institute, RAND, and the Commonwealth Fund — all estimate that the uninsured rate among non-elderly adults has been reduced by between one-fifth and nearly one-half since late 2013. For more information on these survey results, see Matt Broaddus and Edwin Park, “Understanding the Census Bureau’s Upcoming Health Insurance Coverage Estimates,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 11, 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/research/understanding-the-census-bureaus-upcoming-health-insurance-coverage-estimates?fa=view&id=4199#privateSurveysShow.

[4] Montana, which had the ninth-largest drop in its uninsured rate, was the one non-expansion state in the top ten. Montana’s legislature recently approved expansion once the state secures a waiver from the federal government to do so. Dan Witters, “Arkansas, Kentucky See Most Improvement in Uninsured Rates,” Gallup, February 24, 2015, http://www.gallup.com/poll/181664/arkansas-kentucky-improvement-uninsured-rates.aspx.

[5] For more information on the Medicaid expansion’s potential impacts on state budgets, see January Angeles, “How Health Reform’s Medicaid Expansion Will Impact State Budgets,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised July 25, 2012, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3801.

[6] Deborah Bachrach, Patricia Boozang, and Dori Glanz, “States Expanding Medicaid See Significant Budget Savings and Revenue Gains,” State Health Reform Assistance Network, April 2015, http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2015/rwjf419097. Arkansas’ figures are based on interviews with state officials.

[7] See Bachrach, op cit. Kentucky’s figures are based on a February 2015 analysis prepared for the state of Kentucky by Deloitte Consulting, http://governor.ky.gov/healthierky/Documents/medicaid/Kentucky_Medicaid_Expansion_One-Year_Study_FINAL.pdf.

[8] Bachrach, op cit.

[9] Andrew Kitchenman, “Christie’s Budget Cuts $148M from Hospital Charity Care,” New Jersey Public Radio, February 25, 2015, http://www.wnyc.org/story/christies-budget-cuts-148m-hospital-charity-care/.

[10] Based on documents from the state’s Department of Human Services’ Division of Management and Budget.

[11] New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee, 2014 Post-Session Review, April 2, 2014, http://www.nmlegis.gov/lcs/lfc/lfcdocs/April%202014.pdf.

[12] Bachrach, op cit.

[13] Stan Dorn, Norton Francis, Laura Snyder, and Robin Rudowitz, “The Effects of the Medicaid Expansion on State Budgets: An Early Look in Select States,” Kaiser Family Foundation, March 11, 2015, http://files.kff.org/attachment/issue-brief-the-effects-of-the-medicaid-expansion-on-state-budgets-an-early-look-in-select-states.

[14] Bachrach, op cit.

[15] For-profit health systems like Community Health Systems, HCA, and LifePoint all reported greater-than-expected revenues in the first half of 2014, especially from their hospitals in Medicaid expansion states. Pricewaterhouse Coopers, “The health system haves and have nots of ACA expansion,” September 2014, http://www.pwc.com/us/en/health-industries/health-research-institute/assets/pwc-hri-medicaid-report-final.pdf.

[16] Thomas DeLeire, Karen Joynt, and Ruth McDonald, “Impact of Insurance Expansion on Hospital Uncompensated Care Costs in 2014,” US Department of Health and Human Services, September 11, 2014, http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/2014/uncompensatedcare/ib_uncompensatedcare.pdf.

[17] DeLeire, Joynt, and McDonald, op cit.

[18] Paul Cunningham, editor, “Survey Reveals Private Option Impact on Hospitals,” Arkansas Hospital Association, November 3, 2014, http://www.arkhospitals.org/archive/notebookpdf/Notebook_11-03-14.pdf.

[19] Jim Haynes, “April 2014 Hospital Financial Results,” Arizona Hospital and Healthcare Association, June 13, 2014.

[20] Rachel Garfield, Anthony Damico, Jessica Stephens, and Saman Rouhani, “The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid — An Update,” Kaiser Family Foundation, November 2014, http://files.kff.org/attachment/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid-issue-brief.