Note: For more recent analysis reflecting the Congressional Budget Office’s cost estimates, please see

CBO: 24 Million People Would Lose Coverage Under House Republican Health Plan.

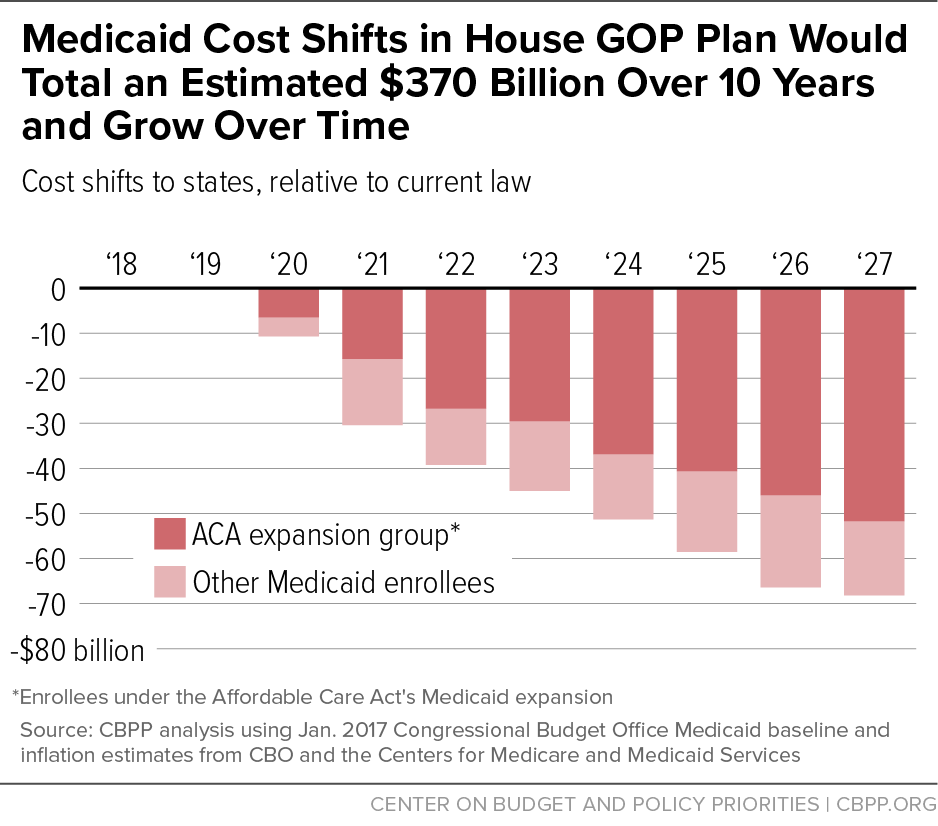

In last week’s address to a joint session of Congress, President Trump promised that any changes to Medicaid would “make sure no one is left out.” [1] The House Republican health care plan announced this week violates that promise. Its $370 billion in Medicaid cost shifts to states would jeopardize coverage and access to care for tens of millions of low-income people. (See Figure 1.)

House Republican leaders have made the unusual choice to bring their plan to a vote in the House Energy and Commerce and Ways and Means Committees without public Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis of its effects on coverage and spending and revenues.[2] But even without CBO estimates, the consequences of the House plan’s major Medicaid proposals are clear.

-

The House plan would effectively end the Affordable Care Act (ACA)’s Medicaid expansion. Under the House plan, states that wanted to continue enrolling low-income adults in expanded Medicaid coverage after 2019 would have to pay 2.8 to 5 times their current-law cost for each new enrollee. The higher cost would apply both to enrollees who are new to Medicaid and to current enrollees who leave Medicaid for a month or more and then seek to return when they fall on hard times. Because most adult Medicaid enrollees use the program for relatively short spells, the higher cost would apply to the large majority of a state’s expansion program within just two or three years. On top of that, the House plan would also cap the growth of per-beneficiary federal funding for the Medicaid expansion (as well as for the rest of the Medicaid program, discussed below), shifting additional costs onto states.

The combination of these two policies would starve states of the resources needed to continue covering low-income adults. To fully maintain the Medicaid expansion, the 32 expansion states (including the District of Columbia) would have to find an additional $253 billion of their own funds over the next decade compared to current law. By 2022, the increased cost would exceed $25 billion per year. Seven states have passed laws that effectively require their Medicaid expansions to end in response to any federal cost shift; realistically, most or all other states would ultimately have to end their expansions as well. Medicaid expansion currently covers 11 million low-income adults who would have been ineligible for Medicaid, and likely uninsured, under pre-ACA rules.

-

The House plan would cap and sharply cut federal Medicaid funding for seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children. The House plan would impose a per capita cap — a limit on per-beneficiary federal funding — on virtually the entire federal Medicaid program. The cap would limit per-beneficiary funding growth to more than the rate of general inflation but below the projected growth rate of per-beneficiary costs in Medicaid (and the health care system as a whole). This proposal would cut federal funding for Medicaid by an estimated $116 billion over ten years, on top of the cuts to the Medicaid expansion. Cuts would grow over time, reaching about $20 billion annually by 2027, and would adversely affect all states, not just those that chose to adopt the ACA’s Medicaid expansion.

Faced with these cuts, states would either have to make up the difference from their own budgets or cut Medicaid coverage, services, provider reimbursement rates, or some combination. Outside of Medicaid expansion, about 17 percent of federal Medicaid spending is for seniors, about 40 percent for people with disabilities, and about 25 percent for children.

The Medicaid cuts in the House plan would largely or entirely pay for high-income tax cuts. The plan would repeal Medicare taxes on high-income individuals as well as drug company, insurer, and other fees that helped finance the ACA’s coverage expansions. The House bill’s tax cuts would cost about $600 billion over ten years, according to Joint Committee on Taxation estimates.[3] The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center estimates that more than half the value of these tax cuts would go to households with incomes over $1 million, who would receive tax cuts averaging more than $50,000 per year. [4]

The remainder of this paper analyzes the House plan’s Medicaid expansion cuts and per capita cap in more detail. It is the first in a series of analyses examining the House plan’s impact on health care access, affordability, and quality. Subsequent analyses will examine other proposals in the House plan, including its new tax credits that take the place of the ACA’s premium credits and cost-sharing subsidies and its other Medicaid provisions.

The House Plan and Medicaid Expansion

The ACA offered states the opportunity to expand Medicaid coverage to low-income adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. For states that took up that option, the federal government initially covered 100 percent of the cost and, under current law, will cover 90 percent of the cost on a permanent basis. That “enhanced match” is higher than the regular matching rate states receive for other Medicaid expenditures, for which the federal government covers 50 to 75 percent of costs, depending on the state.

The House plan would end the ACA’s enhanced match for all new and returning expansion enrollees beginning in 2020. It would also impose a per capita cap on Medicaid funding that would limit the growth rate of federal funding for the expansion (as well as for the rest of the program). The combination of these policies would likely make expansion unsustainable for states, ultimately forcing most or all of the 32 states that took up the ACA’s Medicaid expansion to end it.

Under the House plan, states would retain the enhanced match for people who enroll in expanded Medicaid coverage before January 1, 2020 and remain continuously enrolled (without more than a one-month break in coverage). Starting in 2020, however, states would have to pay 2.8 to 5 times their current-law costs for otherwise-similar people who newly enroll or return to the program after that date. For example, states would receive the enhanced match for a low-wage worker who loses job-based health coverage in 2019, but not a worker who loses coverage in 2020, and for a young adult who turns 19 and ages out of Medicaid children’s coverage on December 31, 2019, but not on January 1, 2020. Likewise, states would retain the enhanced match for current expansion enrollees who stay continuously enrolled in Medicaid. But they would lose the enhanced match for enrollees who find higher-paying jobs at some point between now and 2020, but need to return to Medicaid at some point in the future when they again fall on hard times.

In Medicaid, as in other programs serving low-income people, a large share of those enrolled frequently move on and off the program as their incomes or other family circumstances change. For example, when Arizona froze Medicaid enrollment for its low-income adult population (which it was covering through a pre-ACA waiver), about 45 percent of people left the program within one year, and about 70 percent within 31 months.[5] Consistent with that, among adults with incomes below the Medicaid expansion income eligibility limit at the beginning of a given year, fewer than half are continuously eligible over the course of one year, and only about 20 percent are continuously eligible over the course of four years, one study found.[6]

As a result, within just a few years, the House proposal to end the enhanced match for new and returning enrollees would have almost the same fiscal consequences for states as earlier Republican proposals to end the enhanced match altogether.

The reduction in the federal matching rate for the expansion, combined with the House bill’s per capita cap (discussed further below), would require the 32 current expansion states to increase their own spending on Medicaid by an estimated $253 billion over ten years in order to maintain their expansions. In 2027, this means these states would have to spend more than four times as much to continue expansion as under current law. (See the appendix for an explanation of these and other estimates in this paper.)

In seven states (Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Mexico, and Washington), these higher costs would automatically “trigger” immediate or eventual termination of the Medicaid expansion, without additional action by state policymakers. Laws in these states either explicitly require the expansion to end if the federal matching rate decreases, or they require the state to act to prevent an increase in state Medicaid costs.

But in practice, due to the size of the cost-shift, most or all of the other 25 states that have expanded Medicaid would also have to end their expansions once the House cuts took effect. This is especially likely since, under the House plan, funding cuts for the expansion population would be coupled with additional federal Medicaid funding cuts for the rest of states’ Medicaid programs, as discussed below. [7]

Thus, within just a few years, millions of low-income adults who would have been covered by Medicaid would instead be uninsured, reversing gains in access to care, treatment for opioids or other substance use disorders, mental and physical health, and financial security.[8] In addition, hospitals and states would see their uncompensated care costs shoot back up toward pre-ACA levels.[9] While states would drop the expansion over a period of time, the ultimate result would likely be similar to what would have resulted if the House bill had simply repealed the Medicaid expansion, as under the repeal bill vetoed in 2016.[10]

In addition to its cuts to the expansion, the House plan would, starting in 2020, impose a per capita cap on the entire Medicaid program (including for the expansion population), limiting the growth of per-beneficiary federal funding for Medicaid. Specifically, the Medicaid caps would grow with the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index (M-CPI). This is below the growth rate that CBO currently projects for Medicaid per-beneficiary spending by an average of 0.2 percentage points annually.

We estimate that this proposal would cut federal Medicaid funding for seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children by $116 billion over ten years, on top of the House plan’s cuts to the expansion. The cuts would grow over time, reaching about $20 billion annually by 2027.

Medicaid is already highly efficient, with lower per-beneficiary costs and slower-growing per-beneficiary costs than private health insurance.[11] Moreover, states already enjoy expansive flexibility in the design of their Medicaid programs and how they deliver care. For example, they have already adopted innovative delivery system reforms that improve quality of care while lowering costs. (The House Republican plan doesn’t offer states any meaningful new tools that would somehow let them absorb these large cuts in federal funding without cutting coverage.) The federal funding cuts proposed in the House plan would thus force states to restrict eligibility, reduce the services Medicaid covers, cut payments to hospitals and other providers, or, most likely, a combination of all three approaches to rationing care. In addition to the millions of low-income adults who have newly gained coverage under the expansion, the House plan thus jeopardizes coverage and services for the remaining 63 million children and families, seniors, and people with disabilities who rely on Medicaid.

Converting Medicaid to a per capita cap would also make it highly vulnerable to additional cuts in the future. With federal Medicaid funding delinked from the actual cost of providing health care to vulnerable Americans, it would be easy for policymakers to come back and ratchet down the already arbitrary per-beneficiary caps to pay for other priorities in the future.

These harmful consequences are why the AARP; governors across the country; the American Hospital Association; the American Heart Association, the American Diabetes Association, the American Cancer Society, and other patient advocates; and numerous groups that speak for seniors and people with disabilities have warned against converting Medicaid to a per capita cap. (See box.) The House proposal also violates the National Governors Association’s principle that any changes to federal Medicaid financing should “not shift costs to states.”[12]

Moreover, the $116 billion estimated cost shift understates the actual harm that would result from the House per capita cap proposal. This estimate reflects the reduction in federal Medicaid funding that would occur if federal Medicaid costs over the next ten years grew at the exact rate that CBO currently forecasts. But a per capita cap shifts significant risks, as well as costs, to states. Because states would receive no federal matching funds for any costs above the cap, they would have to bear 100 percent of the costs that result from a public health emergency, a costly new prescription drug, or changing demographics that are not accounted for in the per capita cap formula, none of which CBO’s baseline assumes.

Consider how a per capita cap would have performed in the face of two recent health care challenges.

- The opioid epidemic. As the opioid epidemic has intensified in states around the country, substance use treatment services covered by Medicaid expanded to meet growing need. This occurred not only due to the Medicaid expansion, but also because of how Medicaid currently works. When demand for treatment rose, federal funding automatically rose to cover more than half the cost. Likewise, the federal government partnered with states that chose to improve services, covering more than half the cost of expanding or improving treatment options. Under the House plan’s per capita cap, states would have had to cover the entire cost of rising need on their own. And rather than being able to invest in improving care, many states would have been forced to scale back or ration substance use treatment as the need increased, or to weaken Medicaid coverage for other groups.

- The introduction of Sovaldi. The introduction of Sovaldi, a new drug regimen that cures Hepatitis C, has dramatically improved the quality of life for people with the disease. But it has also imposed large unexpected costs on state Medicaid programs. In calendar year 2014, state Medicaid programs incurred $1.3 billion in total Medicaid costs (before applying any Medicaid rebates) related to Sovaldi, even though only about 2 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries nationwide with Hepatitis C had received the medication.[13] Under current law, the federal government has covered more than half of that cost, on average, leaving states with still significant, but not insurmountable, demands on their budgets. Under the House per capita cap proposal, states would have borne the full cost.

A further concern is how a per capita cap would harm state budgets over the long run as the population ages. Over time, a growing share of Medicaid beneficiaries will be seniors and people with disabilities, whose average health care spending is about 5 times higher than children and other adults. The House plan attempts to address this issue by setting separate caps for seniors and other beneficiary groups. But as the baby boomers age, a growing share of seniors will move from “young-old age” to “old-old age.” People in their 80s or 90s have more serious and chronic health problems and are more likely to require nursing home and other long-term care than younger seniors. For example, seniors aged 85 and older incurred average Medicaid costs in 2011 that were more than 2.5 times higher than those aged 65 to 74.[14] Nothing in the House plan remedies this problem. A per capita cap would thus cut state Medicaid programs by increasingly deeper amounts as more boomers move into “old-old age.”

These examples illustrate that the magnitude of the federal Medicaid funding cuts that states actually experience could be far greater in any given year than the cuts that would result from the cap’s failure to keep up with near-term, anticipated increases in nationwide per-beneficiary costs. They also illustrate why federal funding cuts under a per capita cap would be deepest precisely when need, and demands on state resources, are already greatest.

AARP a

AARP opposes the provisions of the American Health Care Act that create a per capita cap financing structure in the Medicaid program…. In providing a fixed amount of federal funding per person, this approach to financing would likely result in overwhelming cost shifts to states, state taxpayers, and families unable to shoulder the costs of care without sufficient federal support. This would result in cuts to program eligibility, services, or both – ultimately harming some of our nation’s most vulnerable citizens.

Democratic Governors b

Proposals to radically restructure Medicaid with block grants or per capita caps would flood states with new costs. Such plans would severely damage the ability of states to provide quality health care, inhibit innovative cost-control reforms, and devastate communities fighting opioid and substance abuse. Block grants or per capita caps would throw state finances into disarray.

Governor Charlie Baker (R-MA) c

We are very concerned that a shift to block grants or per capita caps for Medicaid would remove flexibility from states as a result of reduced federal funding. States would most likely make decisions based mainly on fiscal reasons rather than the health care needs of vulnerable populations and the stability of the insurance market.

American Medical Association d

Beyond the [Medicaid] expansion, the underlying structure of Medicaid financing ensures that states are able to react to economically driven changes in enrollment and increased health care needs driven by external factors. The Medicaid program, for example, has been critical in helping many states cope with the increased demand for mental health and substance abuse treatment as a result of the ongoing crisis of opioid abuse and addiction. Changes to the program, therefore, that limit the ability of states to respond to changes in demand for services threaten to force states to limit coverage and increase the number of uninsured.

Rick Pollack, President and CEO of American Hospital Association e

Redesigning Medicaid, such as through block grants or per capita caps, could lead to substantial changes in benefits and payments and limit the availability of care for patients.

Center for Medicare Advocacy sign-on letter f

We are writing to urge you to reject proposals to make radical structural changes to Medicaid – by providing federal funding to the states through block grants or per capita caps. These proposals are designed to reduce federal support to state Medicaid programs, not to better serve Americans who rely on Medicaid to access health and long-term care. Medicaid block grants or per capita caps would impose rigid limits on the amount of federal money available to states for Medicaid, endangering the health and well-being of older adults, people with disabilities, and their families.

Consensus Health Reform Principles from: g

Cancer Action Network, American Diabetes Association, American Heart Association, American Lung Association, Cystic Fibrosis Association, JDRF Diabetes Foundation, March of Dimes, Muscular Dystrophy Association, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, National Organization for Rare Diseases, National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease

Coverage through Medicare and Medicaid should not be jeopardized through excessive cost-shifting, funding cuts, or per capita caps or block granting.

a http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/politics/advocacy/2017/03/aarp-letter-to-congress-on-american-healthcare-act-march-07-2017.pdf

b https://democraticgovernors.org/democratic-governors-to-congress-dont-shift-medicaid-costs-to-states/

c http://www.masslive.com/politics/index.ssf/2017/01/baker_defends_parts_of_obamaca.html

d https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/public/washington/ama-letter-on-ahca.pdf

e http://blog.aha.org/post/170224-preserving-medicaid-is-a-priority

f http://www.medicareadvocacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Medicaid-Sign-On-March-2017.pdf

g http://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-public/@wcm/@adv/documents/downloadable/ucm_492352.pdf

Our estimate that the House plan would shift $370 billion in costs to states is based on the Congressional Budget Office’s most recent January 2017 Medicaid and Affordable Care Act (ACA) baseline estimates of spending and enrollment and inflation estimates from the Congressional Budget Office and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Office of the Actuary.

We assume 2016 as the base year for calculating per-beneficiary Medicaid spending estimates for the ACA expansion population and for all other Medicaid enrollees. We then grow these amounts annually by the medical CPI to establish annual per-Medicaid-beneficiary federal spending caps. The caps are assumed to apply first in 2020 for both the expansion population and all other Medicaid enrollees. We also account for the proposed reduction in the federal matching rate for expansion adults who do not remain continuously enrolled in the program after 2020. We compare federal Medicaid spending under these caps to federal Medicaid spending under current law. We assume no behavioral responses by states, such as eliminating the Medicaid expansion coverage, in our estimates. (If, as expected, most or all states drop the expansion over time, the actual federal Medicaid spending cuts over ten years would be considerably larger.)