- Home

- Federal Payroll Taxes

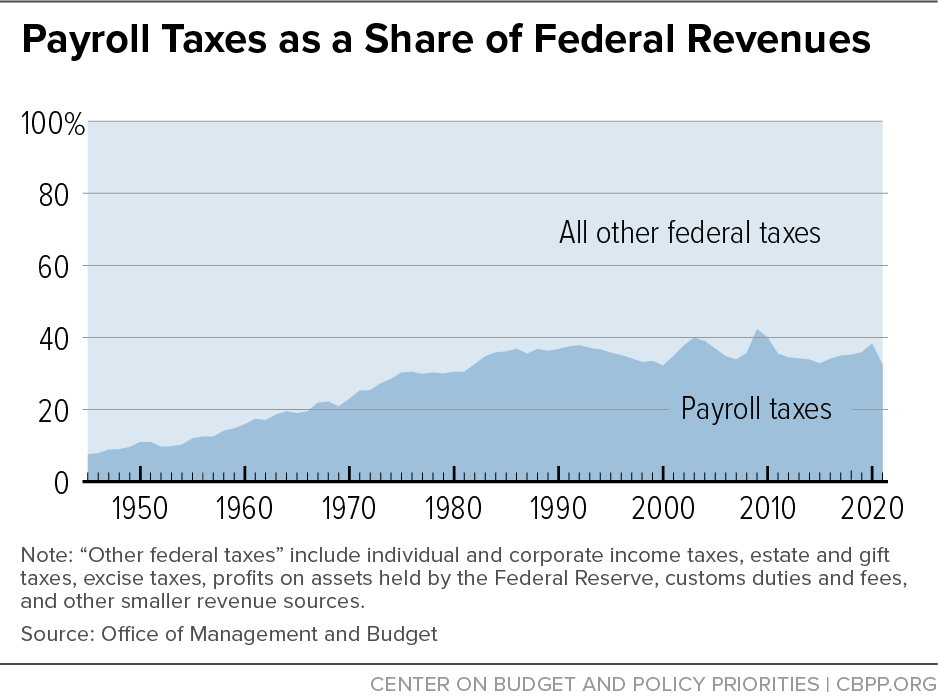

Policy Basics: Federal Payroll Taxes

Payroll Taxes Fund Social Security, Medicare, and Unemployment Insurance

The two main federal payroll taxes levied on wages are known as Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) taxes. Employees and employers both pay FICA taxes: employees usually have them withheld from their paychecks, while employers pay them in addition to any other taxes they owe. However, most economists agree that employees bear the cost of employer payroll taxes in the form of lower wages. The two FICA taxes are:

- the Social Security tax, also known as the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) tax. It is levied at a rate of 12.4 percent (split evenly between employees and employers) up to a maximum amount of an employee’s wages ($147,000 in calendar year 2022). This wage cap is adjusted annually to take account of increases in average wages. In addition, certain compensation, such as employer-provided health insurance and some other fringe benefits, are not subject to the payroll tax. The revenues go toward funding Social Security, which pays benefits to retirees, persons with disabilities, and survivors of deceased workers. For options to boost Social Security’s payroll tax revenues, see Increasing Payroll Taxes Would Strengthen Social Security.

- the Medicare tax, also known as the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) tax. It is levied at a rate of 2.9 percent of wages (split evenly between employees and employers); unlike the Social Security tax, there is no wage cap. Married filers’ earnings over $250,000 (and singles’ earnings over $200,000) are taxed at an additional 0.9 percent, for a total of 3.8 percent on this income. Revenues from the Medicare tax support the hospital insurance portion of Medicare. (There is a 3.8 percent tax on net investment income for high-income taxpayers as well, but it isn’t withheld through the payroll tax or reserved for the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund.)

People who work for themselves pay a self-employment tax — the Self Employment Contributions Act (SECA) tax — to fund Social Security and Medicare. These taxes are equivalent to FICA taxes; the same total rates and caps apply.

The federal and state governments jointly administer the unemployment insurance (UI) system. States levy a payroll tax on employers to finance regular UI benefits for unemployed workers. The federal government also levies a payroll tax, under the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA), that mainly finances the administration of state UI programs. Employers pay an effective FUTA rate of 0.6 percent FUTA tax on the first $7,000 of a worker’s wages, up to $42 per worker per year, while states set their own rates. All financial transactions of the federal-state UI system, including state and federal payroll taxes, are made through the Unemployment Trust Fund, which is recorded as part of the federal budget. (For more, see the Office of Unemployment Insurance, Unemployment Insurance Tax.)

Payroll Taxes Have a Larger Impact on Lower-Income People

Payroll taxes are regressive: low- and moderate-income taxpayers pay a bigger share of their incomes in payroll tax than do high-income people, on average. The bottom fifth of taxpayers paid an average of 6.1 percent of their incomes in payroll tax in 2021, according to Tax Policy Center estimates, while the top fifth paid 5.7 percent and the top 1 percent of taxpayers paid just 2.1 percent. About two-thirds of taxpayers pay more in federal payroll taxes than personal income taxes. These figures include the employer and employee shares of the payroll tax.

However, if one looks at the overall impact of Social Security and Medicare — the benefits they provide as well as the taxes they collect — these programs are progressive. Social Security benefits represent a higher proportion of a worker’s previous earnings for workers at lower earnings levels; and while all Medicare beneficiaries are eligible for the same health care services, high-income beneficiaries pay more in Medicare taxes and premiums. Low-income Medicare beneficiaries are also eligible for help paying for their premiums and cost sharing. Variation in state laws and practices makes it difficult to assess the distributional effect of UI.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.