As part of Policy Futures, we develop and promote ways to protect vulnerable families from the effects of pricing carbon, while effectively reducing greenhouse gas emissions. With that goal in mind, this paper was written in collaboration with Resources for the Future, an independent, nonpartisan organization that conducts rigorous economic research and analysis to help leaders make better decisions and craft smarter policies about natural resources and the environment

This issue brief discusses how a climate rebate implemented as a component of comprehensive carbon tax legislation can protect low- and moderate-income households from the loss in purchasing power they would otherwise experience from higher energy prices due to the carbon tax. It describes how the tax system and existing benefit systems can be used to deliver, at low administrative cost, rebates financed with a portion of carbon tax revenues to a very high percentage of low- and moderate-income households while preserving the policy’s incentives for cost-effective emissions reductions.

A carbon tax is a cost-effective policy tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but the resulting increases in energy prices erode the purchasing power of households’ budgets. Low- and moderate-income households feel the squeeze the most, both because energy-related expenditures constitute a larger share of their budgets and because they have less ability to make investments needed to adapt to higher energy prices (such as buying new, more energy-efficient appliances or home-heating systems) than better-off households.

Well-designed carbon-tax legislation can generate enough revenue to fully offset the hit to the most vulnerable households’ budgets from higher energy prices, cushion the impact for many other households, and leave plenty to spare for other uses (whether deficit reduction, tax reform, or spending for other public purposes). Lump-sum rebates are the best way to provide low-income protection. Both the Waxman-Markey climate bill (passed by the House in 2009) and the Kerry-Lieberman bill (circulated for discussion in the Senate in 2010) included versions of a fully specified low-income “Energy Refund Program,” based on a Center on Budget and Policy Priorities proposal that also serves as a useful guide for how to protect low-income households under carbon tax legislation.

- Well-designed carbon-tax legislation can generate enough revenue to fully offset the hit to the most vulnerable households’ budgets from higher energy prices, cushion the impact for many other households, and leave plenty to spare for other uses.

-

A three-pronged delivery mechanism using existing tax and benefit systems can deliver a lump sum rebate to a very high percentage of low-income households. Such an approach would include the following:

1) A refundable tax credit for workers; 2) a supplement to direct federal payments for retirees, the disabled, and veterans; and 3) a payment delivered using the electronic benefit transfer (EBT) system used to deliver SNAP (food stamp) benefits.

- The EBT mechanism is critical for reaching very-low-income households (primarily families with children) that have very low or no earnings over the year and do not receive Social Security or other similar federal benefits.

- Arguably, the group mentioned above is the most important to reach with a climate rebate, because the loss of purchasing power due to a carbon tax could push these individuals and their children deeper into poverty and create serious hardship.

Among the principles for such protection are that it should not make poor families poorer or push more people into poverty; it should achieve the broadest possible coverage at low administrative cost by using existing, proven delivery mechanisms, rather than creating new public or private bureaucracies; and it should preserve incentives to reduce fossil energy use efficiently.

Subject to ensuring that a climate rebate is large enough to satisfy the criterion of not making poverty deeper or more widespread, policymakers have considerable discretion over its size and scope. The amount of the rebate and how far up the income scale it extends would depend on how much funding policymakers make available for consumer relief in the form of rebates and whether they want to provide larger rebates to a smaller share of the population or smaller rebates to more people.

The main contribution of this issue brief is its identification of a three-pronged delivery mechanism for reaching virtually all the target population, especially those with the very lowest incomes. All households of a given size would receive the same lump-sum amount. Lower-income working households would receive rebates through a refundable income tax credit similar to the Earned Income Tax Credit, beneficiaries of Social Security and certain other federally administered benefit programs would receive them as supplements to their regular payments, and very low-income families would receive them through state human services agencies using the electronic benefit transfer (EBT) system already used to deliver SNAP (food stamp) benefits. Coordination mechanisms would ensure that people don’t receive an overpayment from duplicate rebates.

The EBT mechanism is critical for reaching very-low-income households (primarily families with children) that have very low or no earnings over the year (and are therefore not required to file tax returns) and do not receive Social Security or other similar federal benefits. Arguably, this group is the most important to reach with a climate rebate, because the loss of purchasing power due to a carbon tax could push these individuals and their children deeper into poverty and create serious hardship.

A carbon tax is a cost-effective way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but the resulting higher prices for home energy and gasoline, as well as food and other goods and services with significant energy inputs in their production or transportation to market, erode the purchasing power of households’ budgets. Low- and moderate-income households are most acutely affected because they spend a larger share of their budgets on these items than do better-off consumers.[2] They are also the least able to afford new fuel-efficient vehicles, better home weatherization, and energy-saving appliances because they are already struggling to make ends meet and generally have little or no savings.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions to avoid the damaging and potentially catastrophic costs of global climate change is the policy objective of a carbon tax, but policymakers also recognize the importance of protecting vulnerable households from hardship due to the policy. Fortunately, well-designed carbon-tax legislation can generate enough revenue to fully offset the hit to the most vulnerable households from higher energy prices, cushion the impact for many other households, and leave plenty to spare for other uses (whether deficit reduction, tax reform, or spending for other public purposes)—all without blunting the price signal that is essential for achieving cost-effective emissions reductions.

Channeling some of the money collected through a carbon tax back to households, whether through tax cuts or direct benefit payments, is an obvious way to provide consumer relief—provided, as discussed below, the mechanism actually reaches the targeted beneficiaries. Refunds (in the form of cash rebates or tax cuts) whose size does not vary with an individual household’s energy use are preferable to measures that shield households from facing higher prices and blunt their incentives to conserve energy and invest in energy efficiency. Other things equal, refunds delivered in a way that encourages individuals and businesses to work and invest more efficiently and expand aggregate economic welfare would be preferable to ones that do not.[3]

Other things are not equal, however. Although carbon tax revenues can be returned to households in various ways while maintaining incentives to reduce emissions, no single approach simultaneously provides both incentives to work and invest and robust low-income protection.[4] For example, analysts typically see a “tax swap” of carbon tax revenues for corporate or individual income tax rate cuts as providing the largest expected aggregate economic gains. But such an approach is also the most regressive, since the income tax rate cuts would mainly benefit higher-income households while offsetting only a small fraction of the disproportionately large hit to low-income households.[5] Lump-sum rebates, in contrast, can protect low-income households from becoming further impoverished, but they do not provide the same economy-wide efficiency advantages.[6]

Policymakers do not have to pick one or the other. As this issue brief explains, policymakers can use a portion of the revenues generated by a carbon tax to provide robust but targeted low- income protection, which would leave most of the revenue available to pursue other goals.

A common standard is that rebates should be at least large enough to preserve the purchasing power of the average household in the bottom fifth (quintile) of the income distribution. Under a carbon tax with fixed rebates, energy and energy-related products will cost more. Households that can conserve energy or invest in energy efficiency will get more value for their budget dollar by taking these steps than by using their rebates to maintain current consumption. At the same time, the rebates prevent a decline in the standard of living for low- and moderate-income households that cannot easily reduce their energy consumption.

The rest of this brief is organized into the following sections:

- Lessons from analysis by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) of the Waxman-Markey comprehensive climate legislation, passed by the House in 2009.

- Principles to guide the development of low-income protection mechanisms as part of a federal carbon tax policy.

- Two policy design considerations: How large should rebates be and who should get them? And what are the best mechanisms for delivering these rebates so that they reach the target population?

- A three-pronged approach to delivering rebates, funded by a portion of carbon tax revenues, that could achieve broad coverage among low- and moderate-income households.

- Implications of regional variation and other sources of differential impacts across households for the design of consumer relief under a carbon tax.

The American Clean Energy and Security Act (known as Waxman-Markey after its sponsors), which the US House of Representatives passed in 2009, proposed a cap-and-trade mechanism rather than a carbon tax to control emissions,[7] but lawmakers at that time faced the same low-income protection issues as lawmakers today would face with a carbon tax. Waxman-Markey included a low-income “Energy Refund Program” that remains a good guide to protecting low- and moderate-income households efficiently and effectively.[8] Legislation introduced by Senators John Kerry and Joe Lieberman took a similar approach to low-income protection.[9] As described below, this approach can be adapted readily to address the same issues under a carbon tax.

In its estimate of the budgetary costs of Waxman-Markey,[10] CBO decided to treat the projected market value of all the emissions allowances supplied by the federal government—whether they were sold at auction or distributed freely to certain entities—as government revenue. CBO then treated freely distributed allowances as budget outlays on the same basis as programs financed with the revenue collected from auctioning allowances.

This approach makes it clear that a carbon tax of, say, $30 a ton that held emissions to a certain amount in a year would impose the same costs on households and generate the same amount of revenue to mitigate some of those costs as a cap set at that level of emissions—since the allowance price consistent with that level of emissions would also be $30 a ton. The analysis of the distribution of household costs and benefits under a carbon tax is essentially the same as the analysis under cap-and-trade. CBO’s economic analysis of Waxman-Markey[11] would likely have been little different had it been analyzing a carbon tax aimed at achieving the same level of emissions reductions and using the revenues for the same purposes as Waxman-Markey did.

Analyses like these do not provide a complete accounting of costs and benefits, however, since they do not estimate the benefits from reducing the costs and risks of climate change itself. In other words, they look only at the gross costs imposed on households from putting a price on carbon to reduce emissions, the gross financial benefits to households arising from the uses to which the revenues are put (such as rebates to low-income households), and the distribution of those costs and financial benefits across households at different levels of income.

In its economic analysis, CBO assumed that the costs of Waxman-Markey would be incurred in the form of higher consumer prices for goods and services (in other words, that producers would pass on to consumers the costs of cutting emissions to the capped level and holding allowances for remaining emissions[12]). Changing only the mechanism—from cap-and-trade to a carbon tax—would not change the results of such an analysis.

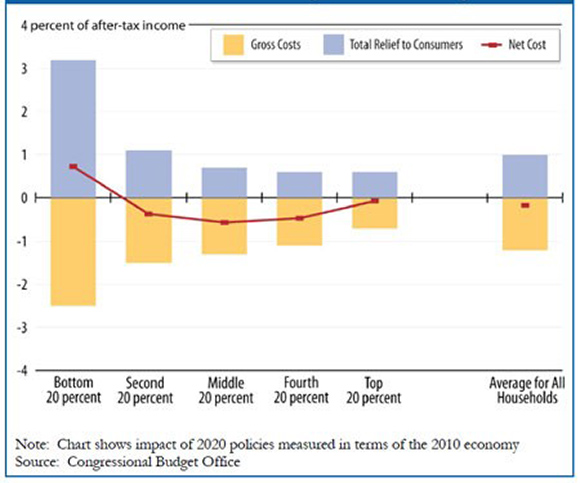

CBO found the standard result that the compliance costs due to putting a price on carbon when prices are passed on to consumers are regressive, with lower-income households bearing a larger relative burden than higher-income households. Because the low-income protections in Waxman-Markey were robust, however, the average household in the lowest quintile of the income distribution also benefited disproportionately from the ways the revenue was used and, on balance, came out slightly ahead.

Costs slightly outweighed benefits for the average household in every other quintile (Figure 1). In fact, aggregate costs slightly outweighed aggregate financial benefits, and the average for all households was a small net loss. That’s because the total revenue available for rebates and other uses was somewhat smaller than the total costs imposed.

The bulk of the gross costs of complying with an emissions cap or a carbon tax is the cost of allowances purchased or taxes paid by those who continue to emit. These are costs to households but revenues to the government, which in turn uses those revenues to provide benefits to households in various forms (rebates, tax cuts, deficit reduction, or program spending). The remaining costs are the costs incurred by businesses and households as a result of the activities they engage in to reduce emissions to comply with the cap or avoid the tax. CBO offers examples such as installing insulation or generating electricity from natural gas rather than from coal, as well as inconvenience costs, such as driving less. These costs, which are the net costs to households in the aggregate, do not generate offsetting revenue.[13]

In general, a market-based approach to reducing emissions, like a carbon tax or cap-and-trade program, gives businesses and households more flexibility to find ways of reducing emissions than a regulatory approach that requires them to adopt specific emissions control measures or sets sector-specific targets. And generally, the net cost of meeting any particular emissions target will therefore be lower under a market-based approach.

The cost-effectiveness of a carbon tax (or cap-and-trade) arises due to the stronger price signal it generates to prompt emissions reductions. But that stronger price signal produces substantially larger gross household costs than a regulatory approach in which no tax (or allowance) costs—only the costs of the measures needed to reduce emissions—get passed on to households.

Thus, the importance of protecting low- and moderate-income households from increased hardship is more acute under a carbon tax than under a regulatory approach. For the economy as a whole, however, a carbon tax is a more cost-effective way to reduce emissions—and it generates more than enough revenue to offset its regressive effect on low- and moderate-income households.

Based on CBO’s Waxman-Markey analysis, CBO senior adviser Terry Dinan reports that the aggregate gross cost to households in the bottom quintile under a similar carbon tax would equal roughly 12 percent of the gross revenue collected from a carbon tax, and aggregate gross costs in the second quintile would be roughly 15 percent of gross revenue. After taking into account increased costs to the federal government from having to pay higher energy prices and lower income tax receipts arising from lower wages and profits under a carbon tax, the net revenues would be somewhat smaller than the gross revenues, and the aggregate costs to households in the bottom two quintiles would be somewhat higher as a share of net revenues.[14]

In principle, therefore, if these estimates remain approximately correct, well under a sixth of carbon tax revenue would be sufficient to satisfy the equity criterion that a carbon tax not increase the amount or depth of poverty in the bottom quintile, and well under a third would be sufficient to protect the low- and moderate-income households in the bottom two quintiles.

Policymakers can design a climate rebate to offset the regressive effects of a carbon tax on low- and moderate-income households. The approach described below builds on existing tax and benefit delivery mechanisms to reach nearly 95 percent of households in the bottom quintile virtually automatically (and an even higher percentage in the next quintile). With effective outreach, the coverage percentage could be higher still.

The approach would not require new bureaucratic structures, and the administrative costs would be relatively low compared with alternative delivery mechanisms. The size of the rebate and how far up the income scale it extends would depend on the amount of funding that policymakers make available for consumer relief in the form of rebates and whether they want to provide larger rebates to fewer people or smaller rebates to a larger number of people. The approach is designed to achieve robust low- and moderate-income relief in accordance with the following principles.

A carbon tax should not make the poor poorer or push more people into poverty. To avoid that outcome, climate rebates should be designed to fully offset the effect of a carbon tax on the purchasing power of low- and moderate-income households as a group. For some time, policymakers have recognized the importance of explicitly addressing the effects of market-based climate policies like a carbon tax and cap-and-trade on low-income households. In 2009, for example, the US Carbon Action Partnership (USCAP), an influential group of large businesses and environmental groups, issued a blueprint for legislation on climate change that explicitly endorsed direct rebates for low-income households to mitigate harm.[16] Both Waxman-Markey and the Kerry-Lieberman Senate bill met that objective. The principle that low-income households as a group should not be made worse off was also a guiding principle in major budget proposals such as the Simpson-Bowles deficit reduction plan.[17]

Climate rebates should be delivered using mechanisms that reach all or nearly all eligible households. Eligible working households could receive climate rebates through the tax code, via refundable tax credits. But many low-income households are elderly, unemployed (especially during recessions), or seriously disabled. Such households with incomes below the threshold that would require them to file federal income tax returns could remain nonfilers and thus miss out on climate rebates for which they would be eligible. Climate rebates should reach these households as well.

Funds set aside for consumer relief should go to intended beneficiaries, not to administrative costs or profits. Accordingly, policymakers should provide assistance to the greatest degree possible through existing, proven delivery mechanisms rather than new public or private bureaucracies.

Larger households should receive more help than smaller households because they have higher expenses. Families with several children generally consume more energy, and consequently face larger burdens from increased energy costs, than individuals living alone—although economies of scale within the household mean that costs do not increase in the same proportion as family size (e.g., a family of four would have less than four times the costs of an individual with the same income). Varying the climate rebate with family size would conform to other tax benefits, like the earned income tax credit (EITC) and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps), that vary by household size.

Higher home energy prices are only one channel through which a carbon tax affects household budgets. Higher gasoline prices are another, but goods and services across the economy use energy as an input or for transportation to market. Furthermore, many low- and moderate-income households pay utility costs in their rent rather than directly. Rebates aimed at mitigating harm should reflect all the direct and indirect channels through which a carbon tax affects household budgets.

Rebates provide benefits to consumers to offset higher costs while still ensuring that consumers face the right price incentives in the marketplace and reduce consumption accordingly. A consumer relief policy that suppresses price increases in one sector, such as electricity, would be inefficient because it would blunt that sector’s incentives to reduce fossil fuel use. That would keep electricity demand higher than what it would be if consumers saw electricity prices rise, and it would place a greater burden on other sectors and energy services to achieve the targeted level of emissions reductions. The result: emissions reductions would be more costly to achieve overall and a higher tax would be needed to achieve any given level of emissions reductions. Consumers might pay less for electricity, but prices would rise still more for other items.

Policymakers face two broad sets of decisions when designing a robust low- and moderate-income climate rebate program to mitigate the effects of a carbon tax. The first set involves the size and scope of the rebate: how large the rebate should be and how eligibility should be set. The second is about how to deliver the rebates to eligible households.

During 2007–2009, when Congress was considering comprehensive climate legislation, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) laid out an approach to consumer relief that provided robust low-income protection but also could be extended as far up the income scale as policymakers wished to provide fixed rebates. This approach illustrates the issues involved in designing effective and efficient consumer relief that fully protects low- and moderate-income households.

Size and Scope of Rebates

CBPP specified a rebate tied to the economic hit to households of different sizes, calculated according to analytical approaches prevailing at the time, including CBO’s analysis of the distributional impact of Waxman-Markey (described above).[18] The size of the rebate would at least equal the average hit to the group of consumers that policymakers decide should be fully compensated.

In accordance with the “do no harm” principle, the rebate should be at least large enough to fully offset the average purchasing power loss of households in the bottom fifth of the income distribution (varied by household size). Waxman-Markey and Kerry-Lieberman set their low-income “energy refund” somewhat higher—at the average hit to households with incomes equal to 150 percent of the federal poverty line. Eligibility for a full rebate was also limited to households at or below this threshold, which is roughly the dividing line between the poorest fifth and the rest of the population.[19]

If policymakers wished to use a larger share of the carbon tax revenue for consumer rebates, they could raise the income level at which households would be eligible for rebates, and perhaps set the rebate amounts at somewhat higher levels, such as the average loss to consumers in the next quintile of the income distribution.[20] The total cost of providing rebates would depend on both the average size of a rebate and how far up the income scale rebates would be provided.

An agency such as the Energy Information Administration would be tasked with determining the annual rebate amounts at the target level of full compensation. That could be done using an approach similar to the one followed by CBO in estimating the gross costs of cap-and-trade for households in different income groups that underlie Figure 1, or any new methodology deemed appropriate for estimating those costs.

The approach just described sets a reference level of income for determining eligibility for a rebate and possibly a different reference level of income for determining the size of the rebate. In each case, however, the income level is adjusted for family size in accordance with current best practices for income distribution analysis. The size of the rebate is higher for larger families but is not a per capita rebate. In other words, a family of four gets a larger rebate than a single individual but not one four times larger, because of the economies of scale in energy use within a household.

Some advocates of a carbon tax pair it with a universal dividend that would divide the revenue from a carbon tax equally among all Americans. Such an approach would likely satisfy the “do no harm“ principle, since the dollar value of the average hit to low- and moderate-income households is below the national average per capita hit.[21] It would, however, disproportionately benefit larger families compared with a rebate adjusted for family size, as described above. The latter is more in accord with the variation in the average carbon footprint of households of different sizes and hence the costs they would bear from measures to reduce that footprint. A universal dividend would also use up all the available revenue, leaving none for other purposes, including deficit reduction, public investment, or tax cuts.

Once the size and scope of a rebate program are determined, policymakers face the challenge of creating a practical way to deliver the rebate to eligible households. CBPP found that three existing mechanisms would be required to achieve the broadest possible coverage. Appropriate coordination would be necessary to ensure that people who might qualify for a rebate through more than one delivery mechanism do not receive multiple payments.

For households required to file a tax return, a refundable income tax credit (i.e., one that provides a refund check to families whose tax credit amount exceeds their income tax liability) is the most effective way to deliver a climate rebate. A tax-based system alone, however, would leave out a large share of households, particularly the lowest-income households. According to the Urban Institute–Brookings Tax Policy Center (TPC), about 14 percent of US households do not file income tax returns (in most cases because they are not required to).[22] Nonfilers include seniors and people with disabilities who do not work and households headed by working-age adults who are jobless for some or all of the year, including some of the poorest families with children in the country.

Seniors, veterans, and people with disabilities who receive Social Security could receive their rebates as direct payments from the federal agency that provides their benefits. This is similar to the policy of direct payments to these individuals that was included in the 2009 economic recovery legislation.

TPC estimated in 2009 that the combination of a refundable tax credit (Making Work Pay) and one-time stimulus payment to those receiving Social Security or veterans’ benefits would reach more than 98 percent of middle-income households. In contrast, it would reach only 87 percent of those in the bottom quintile.[23]

Based on its expertise in evaluating low-income programs, CBPP determined that the best way to reach these low-income households was to use state human services agencies. In particular, households already participating in programs administered by state human services agencies, such as SNAP, along with other low-income households that chose to apply, would receive their monthly climate rebates through these agencies via an electronic benefit transfer system (described below).

Thus, the relief would have three prongs: lower-income working households would receive relief through tax credits, beneficiaries of Social Security and certain other federally administered benefit programs would receive direct rebate payments, and very low-income families would receive rebates through state human services agencies.

The approach outlined above for delivering climate rebates to low- and moderate-income households is designed for a federal carbon tax. It has a national standard for determining eligibility and the size of the benefit a household receives, subject only to a family size adjustment. It preserves households’ incentives to respond appropriately within their ability to the price signal the carbon tax creates, and it does not create any new administrative bureaucracy. This section describes in more detail how such an approach would work.

A refundable tax credit would be available to anyone who files a federal tax return and whose income is below the eligibility limit set for the rebate; tax filers would simply look up the size of their credits in a table similar to the one used now for the earned income tax credit. Like the EITC and the partially refundable component of the child tax credit (known as the additional child tax credit), the climate rebate would phase in as income increased over some income range and then phase out as income rose above a specified level.

The tax credits would be provided annually when households filed their tax returns. Alternatively (and preferably), the tax credits could be provided throughout the year as adjustments to employer tax withholding.[24]

Most refundable tax credits are available only to households with earnings. For example, the additional child tax credit and the EITC are not available to families whose adjusted gross income (AGI) is within the eligibility ranges for these credits but whose income does not come from earnings. The same was true for the Making Work Pay tax credit in the 2009 stimulus act. Policymakers could consider providing climate tax credits to households that have incomes in the eligibility range but whose incomes come in large part from sources other than earnings; this could be done by phasing the credit up at the bottom of the income scale as AGI rises, rather than as earnings rise.

This would be particularly important when a worker is temporarily unemployed and the household is relying on unemployment benefits or interest income from savings. Such a modification would result in more households receiving the credit during recessions, when the number of people relying on unemployment compensation increases.

In addition, as a result of climate change legislation and the dynamic nature of the US economy, some industries are likely to contract while others expand in the shift to a “greener” economy. Providing rebates to individuals with income from unemployment insurance (or trade adjustment assistance) would ensure that people who have lost jobs because of this economic shift do not lose out on consumer relief.

Expanding the credits to taxpayers whose incomes come from nonwage sources would expand coverage among certain low- and moderate-income households. Research shows, however, that many very-low-income households would likely still be left out because they are not required to file tax returns, and do not file even if there is a financial gain to them from filing. For example, one study found that in 2005, 16 percent of the EITC-eligible population were non-filers, and that non-filers made up about two-thirds of the eligible EITC nonparticipants.[25] Lack of awareness, burdensome tax preparation fees, fear of the IRS, and language and literacy barriers may inhibit people who are not required to file from actually filing to receive refunds.

Among those most likely to be missed under the tax-credit delivery mechanism are lower-income seniors and people with disabilities who rely primarily on Social Security or other benefits and are not required to file income tax returns. To reach this group, the most effective policy would be for the Social Security Administration, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Railroad Retirement Board to provide climate rebates directly to people receiving Social Security, SSI, veterans’, or Railroad Retirement benefits whose incomes fall within the limits established for the climate rebate. Married beneficiaries would receive the climate rebate for a household of two; individual beneficiaries would receive the climate rebate for a household of one. The 2009 economic recovery legislation used this approach to provide a one-time $250 payment to all beneficiaries.

CBPP has recommended that the payments to these beneficiaries be made quarterly so that recipients do not have to wait for a once-a-year payment. Payments made more frequently than quarterly might be difficult to administer, since these agencies would need to match beneficiary data so that they do not provide multiple rebates to individuals who are eligible under more than one program.

The group that would not be reached through either tax credits or direct payments from federal agencies would be very-low-income households (primarily families with children) that do not receive Social Security or other similar federal benefits. Arguably, this group is the most important to reach because the loss of purchasing power due to a carbon tax could push these individuals and their children deeper into poverty and create serious hardship.

The best mechanism to reach this group is via state human services agencies that already provide SNAP, Medicaid, and other benefits to a broad array of low-income households. States could readily program the climate rebate into the existing electronic benefit transfer (EBT, i.e., debit card) systems that all states use to deliver SNAP and, in most states, other forms of assistance, including cash aid.

State human services agencies already have the infrastructure needed to gather information about families’ incomes, evaluate eligibility, and issue payments through their existing EBT systems, direct deposit into recipients’ checking accounts, or another electronic payment mechanism.

The Energy Refund Program in the 2010 Kerry-Lieberman draft legislation illustrates how this EBT mechanism would capture a very high percentage of low-income households.[26] It directed state human services agencies to automatically enroll households that participate in SNAP. It also directed agencies to automatically enroll low-income seniors and people with disabilities receiving SSI or the low-income subsidy for the Medicare prescription drug program.[27]

Although these programs reach most of the very poor, including poor families with children, a substantial number of people have incomes below 150 percent of the poverty line but do not participate in SNAP, SSI, or Medicare’s low-income drug subsidy. Accordingly, the Kerry-Lieberman bill included several additional provisions to facilitate participation by eligible low-income households.

It required states to screen all Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) applicants for eligibility for the Energy Refund Program. It also directed the Department of Health and Human Services (the federal agency that would have overseen the Energy Refund Program) to develop streamlined eligibility rules so that states could automatically enroll families receiving Medicaid or CHIP into the program if the information the states collected for Medicaid and CHIP purposes showed they were eligible. This provision would have helped deliver the energy refunds to low-income working families who enrolled their children in Medicaid or CHIP but didn’t participate in SNAP.

It also required streamlined determinations of eligibility for the Energy Refund Program for households in which anyone was eligible for subsidized health insurance under the Affordable Care Act. The same information on gross family income and family size used to determine the individual’s eligibility for the health insurance subsidy would be used to determine the household’s eligibility for the Energy Refund Program.[28] Data-sharing arrangements set up to administer the health insurance programs and subsidies could provide a potential linkage in states that have these arrangements,[29] although political opposition to health care reform in many states has limited the reach of this channel.

Finally, the Kerry-Lieberman bill directed states to establish procedures through which individuals could apply to the state human services agency directly and, if they met the eligibility requirements, be enrolled in the program.

Kerry-Lieberman did not have an explicit low-income Social Security delivery mechanism, but it did direct the heads of the Department of Health and Human Services, the Social Security Administration, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Railroad Retirement Board to provide energy refunds directly to their low-income beneficiaries rather than through the EBT mechanism if the Health and Human Services secretary found that the various agencies could adequately determine income eligibility and prevent multiple refunds, and that this direct payment would be more efficient and would reach a larger number of eligible beneficiaries than the state human services approach.

Delivering climate rebates through existing state eligibility systems and delivery mechanisms would be far less costly to set up and administer than virtually any alternative, while ensuring that the lowest-income families—the group that would be in the greatest danger of utility shut-offs and that generally has the most difficulty managing money—would not be left out and would receive rebates on a monthly basis throughout the year.

CBPP estimates that almost 95 percent of households in the bottom quintile of the income distribution would be reached automatically under this proposal because they already receive Social Security, SSI, veterans’, or Railroad Retirement benefits, they already participate in SNAP, or they already file income tax returns and have earnings. It estimates that more than 98 percent of households in the next two quintiles also would be reached automatically if policymakers decided to extend the rebate that far up the income distribution.[30]

All three of the delivery mechanisms outlined here would play a critical role in providing rebates to low-income families. Although no single mechanism would reach more than about half of households in the bottom quintile, only a bit over 5 percent of bottom-quintile households would not qualify for a rebate under at least one of them. CBPP calculations using 2012 data find the following for households in the bottom quintile:

- About 47 percent received Social Security, SSI, veterans’, or Railroad Retirement benefits and could have qualified for energy refunds for all or part of the year through the federal benefits delivery mechanism.

- About 57 percent received SNAP benefits and could have qualified for energy refunds for all or part of the year through the state human services delivery mechanism. SNAP receipt has been unusually high in recent years because of the weak labor market but is projected to decline as the economic recovery progresses.[31] (A similar calculation using 2005 data found 31 percent would have qualified through SNAP, although future percentages could be somewhat higher.)

- About 21 percent had earnings that would have qualified them for full or partial tax credits.[32] That figure is 32 percent using 2005 data, suggesting that the EBT mechanism takes on a larger role in a weak economy, when households’ earnings are lower.

The EBT mechanism is particularly important for low-income families with children. About one-third of all low-income households with children would receive no rebate at all or only partial rebates if this mechanism were not employed.

As the above percentages for the three delivery mechanisms indicate (they sum to more than 100 percent), some people could qualify for more than one climate rebate because they participate in one or more of the relevant programs and/or also file income tax returns. Accordingly, the following three coordination mechanisms could be employed to avoid overcompensation.

First, state human services agencies would not provide climate rebates to individuals who received Social Security, SSI, veterans' benefits, or Railroad Retirement benefits. Since the state agencies collect and capture detailed information on the sources of income for each household member for benefit eligibility purposes, they could readily adjust the rebates to these households through the EBT system to account for those household members who are receiving rebates through these other programs.

Second, at the end of the year, the Social Security Administration, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Railroad Retirement Board would provide a 1099-type tax form to individuals to whom those agencies had made rebate payments and would also provide this information to IRS. Payments received through the federal benefit programs would, on a dollar-for-dollar basis, offset any climate-related tax credit for which such individuals otherwise would qualify as part of a tax filing unit for that year. Such a mechanism was used in the 2009 recovery act legislation to avoid double payments to people receiving the one-time Social Security payment who also qualified for the Making Work Pay tax credit.

Finally, at the end of the year, state human services agencies would provide information to those adults who had received climate rebates through their state EBT system during the year. The information would show the number of months during the year that these individuals received climate rebates. (The same information would be provided to IRS.) Households that filed tax returns would be asked whether they had received climate rebates through this mechanism, and if so, the number of months the rebates were received. Any climate-related tax rebate for which the household otherwise qualified through the tax system would be reduced proportionally, based on the number of months that the filer and/or the spouse had received rebates through the EBT mechanism. For example, if the household head received climate rebates through EBT for six months, the tax unit’s climate tax credit would be reduced by 50 percent.[33]

These coordination mechanisms would require some new activities by state and federal agencies. If a carbon tax is not effective immediately and the tax is relatively modest in the first couple of years, there should be sufficient lead time to implement the coordination mechanisms effectively in the period between enactment of the climate legislation and actual implementation of the rebates.

The three-pronged approach just described is well suited for delivering lump-sum climate rebates, financed with revenues from a national carbon tax, that reach a very high percentage of low- and moderate-income households. A robust program can fully offset the loss in purchasing power of low-income households as a group. It cannot, however, guarantee that every individual household is made whole. Although the financial benefit from the rebate is the same for all households of a given size, the gross cost of the carbon tax, and hence the net benefits from the tax and rebate together, will not be the same for all. This section explores whether there are systematic sources of household heterogeneity—especially the politically salient issue of regional variation in the size of the hit to household budgets—that policymakers might want to try to take into account in the design of the rebate mechanisms.

A uniform national rebate varied only by family size is progressive. Lower-income households, on average, receive a larger benefit relative to the cost imposed on them by a price on carbon than do higher-income households. If the rebate level is based on the average hit to households of different sizes at a given point in the income distribution, households with lower incomes will be net beneficiaries as a group and the average net benefit will be greatest as a share of income for the lowest-income households.

There is, nevertheless, considerable heterogeneity in the gross cost to households with approximately the same income. Much of this derives from variation in households’ energy consumption patterns: some people drive more, some have better-insulated houses, some have made investments in hybrid automobiles or energy-efficient appliances. At a given income level, households that by accident or design have smaller carbon footprints will be larger net beneficiaries (or incur smaller net costs) with a uniform rebate than those with a larger carbon footprint.

Regional differences play a role as well. Certainly, households living in regions heavily dependent on coal-fired electricity generation will see a bigger effect of a carbon tax on their electricity bills than consumers living in regions with more hydroelectric or nuclear power. Similarly, rural consumers are likely to perceive that they will bear a higher burden because they drive more and use more gasoline.

A proper assessment of the importance of regional variation should look at households’ total energy costs, not just their costs for particular items such as electricity or gasoline. The regions with high gasoline consumption are not necessarily the same as the regions with high utility bills. In addition, a substantial share of the higher energy-related prices would be felt through the indirect effects an emissions cap would have on the prices of other energy-related consumer goods and services, and those effects are likely to be fairly similar across regions.

Assessing regional variation is bedeviled by data limitations and conceptual questions about how to measure and assess equity across regions. Nevertheless, two Resources for the Future (RFF) analyses provide useful insights.

In one, RFF researchers examine the effect of four carbon price paths over the next two decades on electricity prices and carbon dioxide emissions.[34] Focusing on electricity is appropriate because a substantial proportion of emissions reductions will almost surely come from the power sector, and because there is considerable geographic variation in the fossil fuel intensity of electricity generation.

The analysis finds that for relatively low carbon tax rates, the change in electricity prices is modest and relatively evenly distributed across states. Five years out, no state experiences a retail price increase greater than 15 percent due to the carbon tax. At higher tax rates, however, the price consequences are larger and more diverse. States currently highly dependent on cheap coal-fired electricity that will have to transition to cleaner but more expensive generation technologies will see much larger price increases than states whose power sectors are already much less dependent on fossil energy.

The second RFF analysis takes a more comprehensive look at how a carbon tax would affect households’ economic well-being as well as regional variations in that impact.[35] The analysis calculates the net effect on households’ welfare (analogous to the red line in Figure 1) of the gross costs imposed by the carbon tax and the financial benefits conferred by the recycling of the carbon tax revenues back to households.

For present purposes, the relevant piece of the analysis is its evidence on geographic variation in the effect of a carbon tax on the prices of energy goods. Not surprisingly, given the results of the other RFF analysis, the majority of geographic variation is due to variation in the price changes for electricity. The loss from gasoline price increases is larger than that for electricity but varies less across states. Similarly, the effect of other price changes is not significantly different across states. In other words, although the differences across regions in electricity price changes are substantial, the differences in the overall effect of the carbon tax are less significant because changes in electricity prices are only a portion of the total effect.

Importantly, the RFF researchers find that variation among households in the gross losses from higher energy prices is less significant across regions and states than across income quintiles. As discussed earlier, lump-sum rebates are the most effective way to protect low- and moderate-income households and require only a modest share of carbon tax revenues. Policymakers could consider using the rest of the revenue for purposes other than providing lump-sum rebates farther up the income scale without compromising the objective of providing robust low-income protection.

Policymakers understandably may want to consider the possibility of fine-tuning a rebate program to address heterogeneity within income groups and across regions. A fully satisfactory policy response, however, is likely to remain elusive. Adjusting the size of rebates for individual households’ income and location would add considerable complexity and, in the case of regional variation, invite the kinds of formula fights that often bedevil policy development. For those receiving rebates through the tax system, IRS would face the additional difficulty of varying tax credits by jurisdiction. Nevertheless, if there is a reasonable evidence-based case that some states or regions would experience a disproportionate burden from a carbon tax, policymakers could consider using a modest portion of the revenue for grants to those states for the purposes of addressing the higher burdens their residents would face.

A similar approach could be taken to address the disproportionate burden faced by a fraction of low-income households, such as those that rent poorly insulated apartments or have inefficient appliances. These households could have difficulty making ends meet even with the standard rebates. That issue could be addressed by providing additional funds for the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), which provides energy assistance to low-income consumers and often directs aid to those who face utility shut-offs or other hardships. For a variety of reasons, relying primarily or exclusively on LIHEAP to provide low-income relief is far inferior to the rebates described in this issue brief. It can, however, serve a modest but important purpose.

In the end, policymakers will face trade-offs between, on the one hand, the simplicity and low administrative costs of achieving rough justice through uniform rebates and perhaps some ancillary policies like the ones just described and, on the other hand, the complexity and greater administrative costs of trying to take more sources of household heterogeneity into account in setting the size of the rebates.

Under a carbon tax, energy and energy-related products will cost more. Low- and moderate-income households bear a disproportionate burden relative to their incomes, but a lump-sum rebate funded from the revenues generated by the carbon tax is an effective policy tool that can preserve both these households’ purchasing power and the price signal that is essential to cost-effective emissions reductions.

Households with the flexibility to conserve energy or invest more in energy efficiency will get more value for their budget dollar by taking such steps than by using their rebates to maintain their old ways of consumption. At the same time, the rebates prevent low- and moderate-income households that cannot easily reduce their energy consumption from experiencing a significant decline in their already-constrained standard of living.

This issue brief has described one promising way to set the size of the rebate based on the average carbon footprint of households of different sizes in the target population. Other ways of determining the size of the rebate are possible. The primary contribution of this brief is its identification of a three-pronged delivery mechanism for reaching as broad a share of the target population as possible—and doing so virtually automatically and at low expense by using the existing tax system and existing benefit systems.

Using the existing electronic benefit transfer (EBT) system already in place in state human services agencies is the key to delivering climate rebates to the greatest number of the most vulnerable households. The legislative language in the Waxman-Markey bill passed by House in 2009 and the Kerry-Lieberman bill circulated in the Senate in 2010 provide a good guide to implementing that delivery mechanism. This brief suggests coordination mechanisms to avoid overpayments when a household could be eligible for a rebate through more than one mechanism.

A lump-sum rebate does not provide the same incentives to increase work, saving, and investment that are usually ascribed to cuts in marginal tax rates, but such tax cuts are ineffective at reaching the most vulnerable households, as well as being regressive. Moreover, protecting low-income households with rebates absorbs a relatively small share of the revenue generated by a carbon tax, leaving a substantial share free for other purposes, such as tax cuts, deficit reduction, or increased program expenditures.

Finally, the hit to household budgets from a carbon tax varies with the carbon footprint of individual households. A large enough rebate coupled with a good delivery system can fully protect low-income households as a group and prevent poverty from becoming more widespread or deeper, but it cannot fully protect households with a particularly large carbon footprint. With sound delivery mechanisms, however, those households are likely to get a full rebate and substantial, if partial, relief.