Statement by Chad Stone, Chief Economist, on the April Employment Report

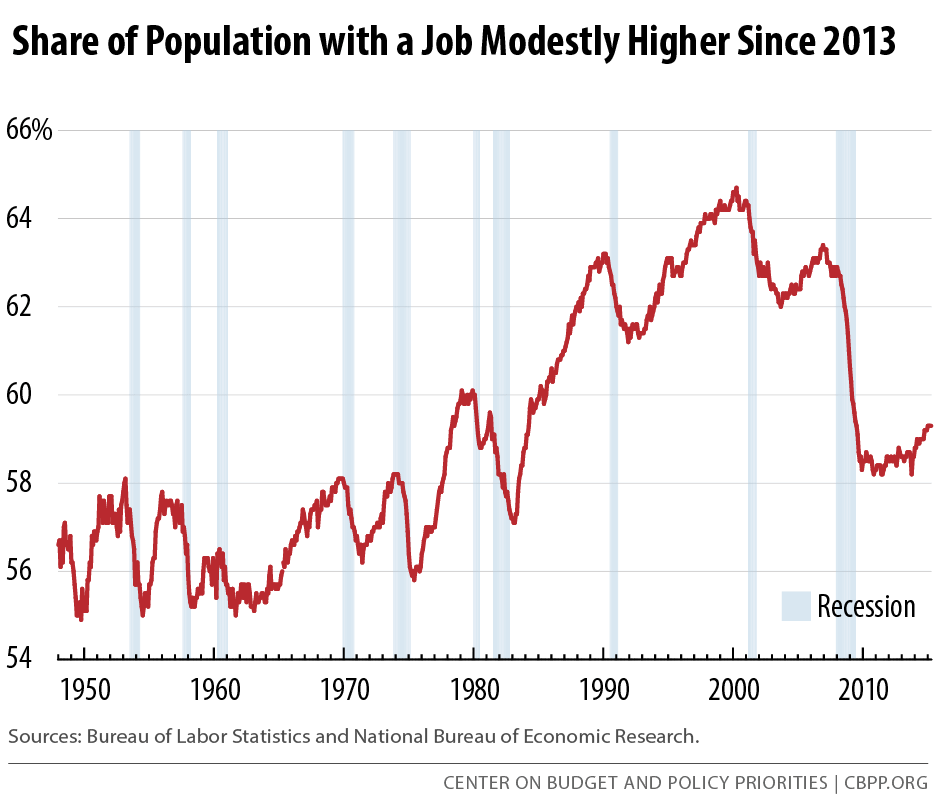

Today’s solid employment report shows the economy continuing to add jobs even though economic growth stalled in the first quarter. But the share of the population with a job, which rose modestly in 2014, also has stalled this year and remains well below pre-recession levels. We’re still waiting for the clear signs of greater labor force participation and faster wage growth that, together with a falling unemployment rate, would justify the Federal Reserve’s beginning to raise interest rates toward “normal” levels for a healthy labor market.

The initial estimate of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the first quarter showed economic growth slowing to a 0.2 percent annual rate, and the March jobs report was disappointing. How much weather and other special factors played a role is hard to assess, but the widening trade deficit in March suggests revised estimates could show even lower first quarter GDP.

For the labor market, the key question is whether the economy will rebound in the second quarter, boosting job creation and labor force participation while reducing unemployment.

The unemployment rate edged down to 5.4 percent in April and labor force participation rose slightly. For the past year, however, the share of the population working or actively looking for work has hovered in the 62.7 to 62.9 percent range, a rate last seen in the late 1970s. Consequently, the share of the population with a job has stayed at 59.3 percent for the first four months of the year.

Inflation and employment both remain below Federal Reserve targets. The Fed should keep interest rates low to encourage stronger demand for goods and services and healthier labor markets.

About the April Jobs Report

Employers reported solid moderate payroll job growth in April. In the separate household survey, the unemployment rate edged down to 5.4 percent and labor force participation rose slightly.

- Private and government payrolls combined rose by 223,000 jobs in April, while job growth in the previous two months was revised down by 39,000. Private employers added 213,000 jobs in April, while overall government employment rose by 10,000. Federal government employment rose by 2,000, state government rose by 1,000, and local government rose by 7,000.

- This is the 62nd straight month of private-sector job creation, with payrolls growing by 12.3 million jobs (a pace of 198,000 jobs a month) since February 2010; total nonfarm employment (private plus government jobs) has grown by 11.7 million jobs over the same period, or 189,000 a month. Total government jobs fell by 569,000 over this period, dominated by a loss of 365,000 local government jobs.

- The job losses incurred in the Great Recession have been erased. There are now 3.5 million more jobs on private payrolls and 3.0 million more jobs on total payrolls than at the start of the recession in December 2007. Because the working-age population has grown since then, the number of jobs remains well short of what is needed to restore full employment. But growth must continue at something like 200,000 or more a month to close the gap in a reasonable period of time.

- Average hourly earnings on private nonfarm payrolls rose by 3 cents in April to $24.87. Over the last 12 months they have risen by 2.2 percent. For production and non-supervisory workers, average hourly earnings rose by 2 cents to $20.90 — 1.9 percent higher than a year earlier.

- The unemployment rate edged down 5.4 percent in April — still 0.4 percentage points higher than it was at the start of the recession — and 8.5 million people were unemployed. The unemployment rate was 4.7 percent for whites (0.3 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), 9.6 percent for African Americans (0.6 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), and 6.9 percent for Hispanics or Latinos (0.6 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession).

- The recession drove many people out of the labor force, and the ongoing lack of job opportunities kept many potential jobseekers on the sidelines and not counted in the official unemployment rate. April’s numbers were a little more encouraging. The labor force grew by 166,000 people and the number of people with a job grew even more — by 192,000. As a result, unemployment fell by 26,000. (The data on household employment and unemployment come from a different survey than those on payroll employment and show considerably more month-to-month variability.)

- The labor force participation rate (the share of the population aged 16 and over in the labor force) edged up to 62.8 percent in April, 3.2 percentage points lower than it was at the start of the recession. As discussed above, however, the labor force participation rate has stayed in the narrow range of 62.7 to 62.9 percent since April 2014. Prior to recent years, the labor force participation rate hasn’t been this low since the 1970s, and growth in participation will be needed to restore normal labor market health.

- The share of the population with a job, which plummeted in the recession from 62.7 percent in December 2007 to levels last seen in the mid-1980s and has remained below 60 percent since early 2009. While this number rose modestly in 2014, it has been stuck at 59.3 percent in the first four months of this year.

- The Labor Department’s most comprehensive alternative unemployment rate measure — which includes people who want to work but are discouraged from looking (those marginally attached to the labor force) and people working part time because they can’t find full-time jobs — was 10.8 percent in April. That’s well down from its all-time high of 17.1 percent in April 2010 (in data that go back to 1994) but still 2.0 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession. By that measure, about 17 million people are unemployed or underemployed.

- Long-term unemployment remains a significant concern. Almost three in ten (29.0 percent) of the 8.5 million people who are unemployed — 2.5 million people — have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. These long-term unemployed represent 1.6 percent of the labor force. Long-term unemployment reached much higher levels and has persisted much longer in the Great Recession and subsequent jobs slump than in any previous period in data that go back to the late 1940s. The worst previous episode was in the early 1980s, when the long-term unemployment share peaked at 26.0 percent (compared with 45.5 percent this time) and the long-term unemployment rate peaked at 2.6 percent (compared with 4.4 percent this time). Moreover, in the earlier episode, a year after peaking at 2.6 percent, the long-term unemployment rate had dropped to 1.4 percent, compared with the current rate of 1.6 percent more than five and a half years after the end of the Great Recession.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.