Thank you for the opportunity to testify. I am Barbara Sard, Vice President for Housing Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The Center is an independent, nonprofit policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting low- and moderate-income families. The Center’s housing work focuses on improving the effectiveness of federal low-income housing programs, particularly the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher program.

The June 2016 report of the Speaker’s Task Force on Poverty, Opportunity, and Upward Mobility noted that “A major obstacle to housing assistance recipients moving up the economic ladder is the lack of individual choice in housing programs and bureaucracies.” It recommends that “To combat this, we should enhance the portability of housing assistance vouchers” and reform the “fragmented” system of thousands of public housing agencies.[1] My testimony will review the evidence concerning the interplay between individual choice and administrative fragmentation in the Housing Choice Voucher program, explain why remedying these problems is important, and recommend solutions Congress could enact. I will also address two legislative proposals that would be unwise. In brief, I recommend that Congress:

- Fund a regional housing mobility demonstration in the final 2017 appropriations legislation.

- Direct HUD to permit consortia to have a single voucher funding contract with HUD rather than a separate one for each agency.

- State explicitly that state laws may not block local housing agencies from forming consortia.

- Direct HUD to make greater use of its authority to consolidate poorly performing agencies.

- Direct HUD to develop and make available technology that could help agencies establish and operate consolidated waiting lists, thereby allowing families that need assistance to submit a single application.

- Modify the voucher administrative fee formula to remove disincentives for forming consortia and encourage greater use of vouchers in higher-opportunity areas.

- Decline to advance or enact H.R. 4816, The Small Public Housing Agency Opportunity Act, which would undermine the goals of increasing efficiency and access to opportunity, and includes other risky provisions.

- Decline to advance or enact legislation to establish a new federal preference for youth aging out of foster care in all major federal rental assistance programs (Rep. Turner’s proposal).

The Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program, the nation’s largest rental assistance program, helps 2.2 million low-income households, including about 1 million families with children, rent modest units of their choice in the private market. But due to funding limitations, only about one in four families eligible for a voucher receives any form of federal rental assistance.

Rigorous studies demonstrate that Housing Choice Vouchers sharply reduce homelessness and other hardships. In addition, vouchers for homeless families cut foster care placements (which are often triggered by parents’ inability to afford suitable housing) by more than half, sharply reduce moves from one school to another, and cut rates of alcohol dependence, psychological distress, and domestic violence victimization among the adults with whom the children live.

By reducing families’ rental costs, housing vouchers allow them to devote more of their limited resources to meeting other basic needs. Families paying large shares of their income for rent spend less on food, clothing, health care, and transportation than those with affordable rents. Children in low-income households that pay around 30 percent of their income for rent (as voucher holders typically do) score better on cognitive development tests than children in households with higher rent burdens; researchers suggest that this is partly because parents with affordable rent burdens can invest more in activities and materials that support their children’s development. Children in families that are behind on their rent, on the other hand, are disproportionately likely to be in poor health and experience developmental delays.[2]

A strong body of research shows that growing up in safe, low-poverty neighborhoods with good schools improves children’s academic achievement and long-term chances of success, and may reduce inter-generational poverty. Studies have also consistently found that living in segregated neighborhoods with low-quality schools and high rates of poverty and violent crime diminishes families’ well-being and children’s long-term outcomes. [3]

Location also can affect adults’ access to jobs, the cost of getting to work, the ease of obtaining fresh and reasonably priced food and other basic goods and services, and the feasibility of balancing child care responsibilities with work schedules.[4]

Vouchers enable families with children to move to safer neighborhoods with less poverty, and thereby enhance their chances of long-term health and success. But reforms are needed to realize the program’s potential in helping families to access neighborhoods of opportunity.

A recent groundbreaking study by Harvard economists Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence Katz found that young children in families that used housing vouchers to move to better neighborhoods fared much better as young adults than similar children who remained in extremely poor neighborhoods.[5] The study provided the first look at adult outcomes for children who were younger than 13 when their families entered the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) demonstration, a rigorous, random-assignment, multi-decade comparison of low-income families who used housing vouchers to relocate to low-poverty neighborhoods to similar families that remained in public housing developments in extremely poor neighborhoods.

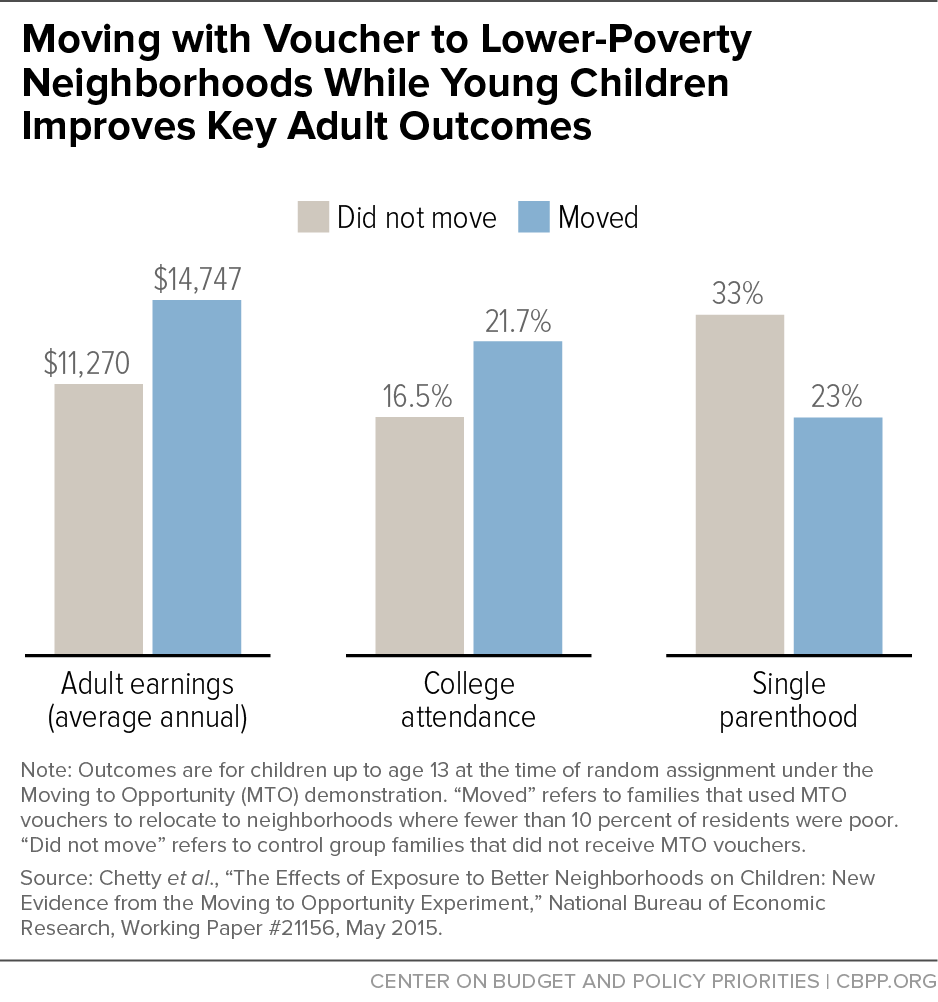

The Chetty study found that young boys and girls in families that used a voucher to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods were 32 percent more likely to attend college and earned 31 percent more — nearly $3,500 a year — as young adults than their counterparts in families that did not receive an MTO voucher. Girls in families that moved to lower-poverty neighborhoods were also 30 percent less likely to be single parents as adults (see Figure 1). MTO’s design imparts confidence to the conclusion that neighborhood differences are responsible for these striking outcomes.

When African American and Hispanic families use housing vouchers, their children are nearly twice as likely as other poor minority children to grow up in low-poverty neighborhoods and somewhat less likely to grow up in extremely poor areas. The voucher program thus has an important, positive impact on minority families’ access to opportunities.

Still, only one in eight (12.9 percent) families with children participating in the HCV program used their vouchers to live in a low-poverty area, where fewer than 10 percent of residents are poor, and 343,000 children in families using vouchers lived in extremely poor neighborhoods in 2014. Vouchers could do much more to help these and other children grow up in safer, low-poverty neighborhoods with good schools.[6]

Many more families would like to use vouchers to move to better neighborhoods — and many housing agencies would like to help them do so — but families typically do not receive the information and assistance they need to make successful moves. In addition, certain program rules,[7] as well as the program’s balkanized administrative structure, make it more difficult for families to use vouchers in high-opportunity areas. In the few cases where families receive assistance from public housing agencies (PHAs) — or partner organizations — that operate regionally, have policies that facilitate using vouchers in higher-opportunity areas, and provide information and assistance to families to move to such areas, thousands have successfully made such life-changing moves.

In a recent paper, I discuss the four sets of interrelated policy changes at the federal, state and local levels that can help more families in the HCV program to live in better locations.[8] Today I want to highlight the importance of streamlining and consolidating program administration to increase efficiency and make it easier for families to use vouchers in opportunity areas; and of providing additional funds to help achieve these goals.

HUD currently contracts with about 2,240 PHAs to administer housing vouchers.[9] These agencies administer as few as four and as many as 99,200 vouchers. Beyond consideration of population and housing need, differences in municipal and county governance as well as state politics have led to this great variation in PHAs’ scale, as well as in their geographic coverage. The result is a complex network of program administration, where multiple agencies, both large and small, often administer vouchers in the same metro areas, sometime with overlapping jurisdictions. The complexity and redundancy of program administration is inefficient, increases program costs, makes federal oversight more difficult, and reduces housing opportunities for families.

In some states, state-level agencies oversee a large share of the federal rental assistance resources. About 30 states (including the District of Columbia) have state-level agencies that administer a portion of the housing vouchers in the state.[10] Other states have created regional entities that respond to the administrative challenge posed by rural areas. In Mississippi, for example, six regional housing authorities administer nearly 75 percent of the state’s vouchers and nearly 15 percent of its public housing units. State or regional administration of rental assistance makes it easier for families to apply for assistance and to choose where to live, and typically provides economies of scale.

In most metropolitan areas, one agency administers the HCV program in the central city and one or more different agencies serve suburban cities and towns. This pattern is the case in 97 of the 100 largest metro areas, where 71 percent of households in the HCV program lived in 2015. In 35 of the 100 largest metro areas, voucher administration is divided among ten or more agencies. This is the case even in mid-size metro areas such as Providence, Rhode Island, and Albany, New York, each of which has at least 35 agencies administering the HCV program.[11]

One reason for this pattern is that HUD in the past allocated voucher funds to hundreds of new small agencies to serve individual suburban towns or to administer special vouchers for people with disabilities, including nearly 700 small agencies in metro areas.[12] These decisions result, at the extreme, in 68 different small PHAs administering the HCV program in the greater Boston metropolitan area (which includes part of southern New Hampshire), in addition to 25 larger agencies and two state-administered HCV programs.

The large number of PHAs administering the HCV program has made its operation more costly and less efficient — as well as less effective for families — than it could be.

Oversight and Operation of Small PHAs Increase Federal Costs

The large number of PHAs increases the cost of federal oversight as well as the cost of local agency administration. In an analysis of opportunities to increase HCV program efficiency, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that “consolidation of voucher program administration under fewer housing agencies . . . could yield a more efficient oversight and administrative structure for the voucher program and cost savings for HUD and housing agencies….”[13]

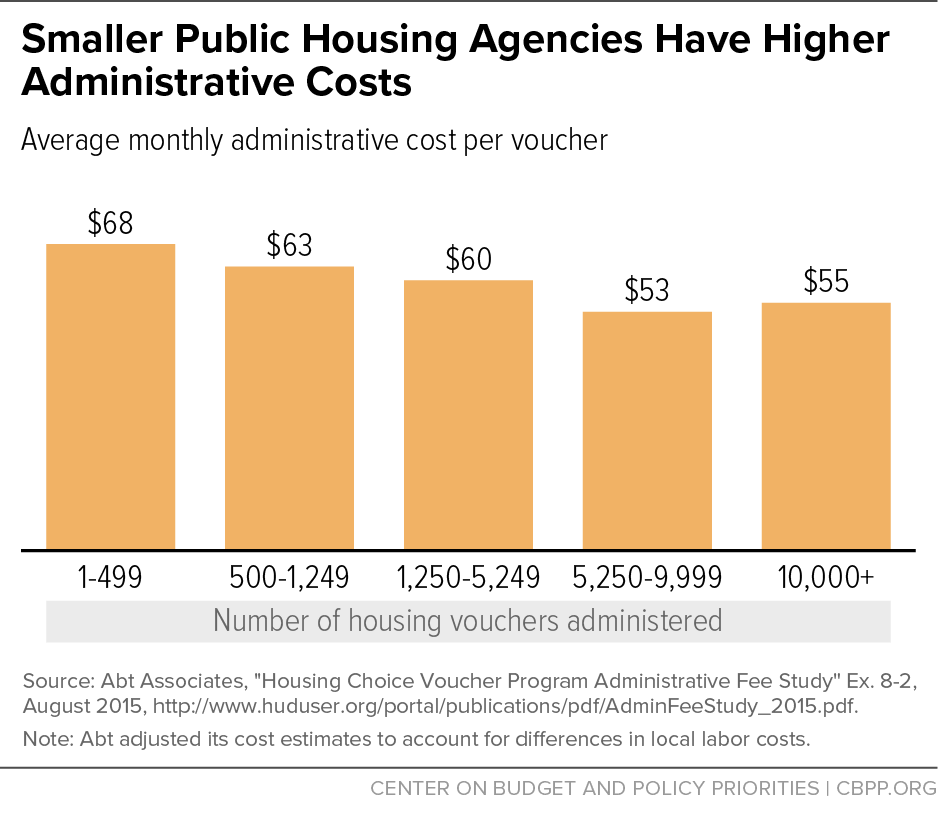

A careful HUD study recently examined the actual costs that high-performing agencies of various sizes incur in administering the HCV program, as well as the financial data that voucher PHAs submit to HUD. It found that PHAs that administered fewer vouchers had significantly higher costs per family served than larger programs (see Figure 2).[14] One significant cost factor is additional staff per voucher in use. This is likely because some basic administrative functions — such as overall planning and staying up to date on program rules — take essentially the same amount of time regardless of the number of vouchers a PHA administers.

Under current policy, HUD gives smaller agencies — those with 600 or fewer vouchers — higher per-unit subsidies for voucher administrative costs, with the payment boost phasing out for larger programs.[15] The recent HUD study recommends paying additional fees for agencies serving fewer than 750 families, with the biggest boost to agencies serving fewer than 250 families and then gradually phasing out the boost to avoid a funding cliff. If federal policymakers maintain current law or adopt the study’s recommendation, the federal cost will be greater than if policymakers decide that agencies should be paid only the amount needed to operate at an efficient scale, without a boost based on the small size of their voucher programs.[16]

Rental units in safe neighborhoods with good schools are more plentiful in some suburban areas than in the central cities or older suburbs, which are more likely to have higher-poverty neighborhoods with lower-performing schools. A recent study by the Urban Institute and other analyses of data from the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s ten-site Making Connections Initiative, a comprehensive place-based initiative, found that interventions that don’t support relocation to suburban areas with high-quality schools “cannot reasonably expect improved educational outcomes for children, given the educational environment in most cities.”[17]

But the balkanization of metro-area HCV programs among numerous housing agencies often impedes greater use of vouchers in higher-opportunity areas. Families living in high-poverty neighborhoods in central cities or older suburbs with increasing poverty may have more difficulty using a voucher to move to such areas than if a single agency, or consortia of agencies, served the metro area. Agency staff in higher poverty jurisdictions may be unfamiliar with housing opportunities elsewhere and unlikely to encourage families to make such moves, particularly because under current policy agencies lose administrative fees when families use their voucher in another jurisdiction. (Typically, agencies have to transfer 80 percent of the HUD-provided administrative fee for a voucher used in another PHA’s jurisdiction to the receiving PHA.) And PHAs in destination communities may be reluctant to accept new families or assist them in finding a willing landlord, seeing newcomers as potential competition with current residents for scarce rentals. Racial prejudice also may play a role.

In addition to these barriers to using housing vouchers to move to higher-opportunity areas, families most in need of affordable housing may have less chance to receive it in metro areas where multiple agencies administer federal rental assistance. To maximize their opportunity to receive housing assistance, families should apply to housing agencies throughout the region. This can be time consuming and costly, particularly if many agencies in the area administer federal rental assistance and require in-person applications. It also can be confusing, as GAO found, which can keep families from submitting all the applications they should to have the best chance to obtain the assistance they need.[18]

A single application for assistance to all housing agencies operating in a metropolitan area or rural county would help families in need. Consolidated waiting lists also would reduce administrative costs for agencies, whose staff now must maintain waiting lists with many duplicative applicants. Forming consortia would facilitate the use of a single application and waiting list for the member PHAs. But even without that change, PHAs could join together to implement a streamlined application process. For example, in Massachusetts, an organization representing local housing agencies oversees such a list for most of the voucher PHAs in the state, and the participating agencies have saved significant staff time as a result. Similarly, recognizing the importance of a single application point for families seeking assistance, the Utah legislature recently required that all voucher-administering agencies in each county use a single consolidated waiting list.[19]

HUD recently strengthened requirements for PHAs to make available diverse landlord lists or other resources that include units in areas outside of poverty or minority concentration, provide enhanced briefings to families about the potential benefits of lower-poverty areas, and take other steps to increase housing choice. Without additional funding, few agencies will have the resources needed to go beyond these requirements and help more families with vouchers rent in higher-opportunity areas.[20]

There have been efforts in some metro areas, funded through a variety of sources, to provide intensive mobility assistance to families that want to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods, but only about 15 such programs operate today.[21] Programs in the Baltimore and Dallas areas have reported significant success in moving substantial numbers of families to — and helping them remain in — much lower-poverty, predominantly non-minority communities. These initiatives provide families with assistance in locating available units, higher rental subsidy levels, payments for security deposits and other moving costs, and counseling to help them adjust to such neighborhoods. They provide similar services to families for at least one subsequent move to help them remain in designated opportunity areas. These programs operate on a regional basis covering at least the central city and many suburban areas, thereby avoiding the barriers created by separate agency service areas.[22]

These local initiatives illustrate that housing vouchers can enable more families to move to safe, lower-poverty neighborhoods with greater opportunities, but it will require both policy changes and additional resources to do so at a larger scale.

Overcoming the administrative divisions created when multiple PHAs serve a housing market is challenging. Cumbersome federal portability policies — which hinder families’ ability to move to low-poverty suburban areas with better schools — exacerbate these difficulties and create financial disincentives for housing agencies to encourage such moves. HUD recently made modest improvements in the portability process, but it left unchanged several key obstacles to families using vouchers to move to areas served by different PHAs.[23] Congress could assist by providing the $15 million that the President’s fiscal year 2017 budget requests for a regional housing mobility demonstration. HUD — or Congress — could substantially lessen these problems by encouraging additional agencies beyond those benefiting from this small demo to form regional consortia, requiring consolidation of poorly performing agencies with others, and modifying policies governing administrative fees.

The President’s 2017 budget includes $15 million for a new Housing Choice Voucher Mobility Demonstration. This three-year demonstration would help public housing agencies in ten regions collaborate on initiatives to help low-income families use existing vouchers to move to higher-opportunity neighborhoods. A growing number of communities are interested in developing or strengthening regional collaborations — including forming consortia — to facilitate housing mobility but are stymied by the lack of funding to support the related administrative costs. Demonstration funds could be used to support staff time to plan for regional collaboration and align policies and administrative systems across public housing agencies, as well as to cover costs of enhanced landlord recruitment and other activities to expand families’ housing choices. The one-time funding also would support research to learn what strategies are most cost-effective.

The Senate’s version of the fiscal year 2017 appropriations bill for HUD, S. 2844, includes $11 million for this purpose plus $3 million to research what strategies are most effective, but the House Appropriations Committee-approved bill omits similar funding.

The mobility demonstration is a modest investment that could improve outcomes for children by enabling more families to use their housing vouchers to live in safe neighborhoods where their children can attend good schools, helping to reduce intergenerational poverty. It helps address both key barriers I’ve focused on today — the division of metro areas among multiple housing agencies and the lack of funds for mobility assistance — and deserves Congressional support.

If PHAs in a metro area could form a consortium in which they each retain their local board but together have a single voucher funding contract with HUD, families would be able to use their vouchers to move relatively seamlessly among the cities and towns in the consortium. (Consolidation of separate housing agencies to form a single metro-wide PHA could have greater benefits but also faces greater political hurdles; for many PHAs, the ability to retain their independent identity is a paramount concern. This makes it more likely that PHAs would join a consortium to achieve administrative economies of scale than formally consolidate with other agencies.[24]) Under HUD’s current rules, however, agencies have little incentive to form consortia, and when they do, they still lack a single funding contract with HUD.[25]

Enabling agencies in a consortium to function as a single entity for funding, reporting, and oversight purposes would substantially reduce PHAs’ and HUD’s administrative burdens. Agencies would also benefit from greater economies of scale. GAO notes, for example, the greater efficiencies that are possible when small agencies join together to hire inspectors or when a voucher program is large enough to generate sufficient administrative fees to support a fraud detection unit.[26] Economies of scale also could free up staff time to take advantage of program options such as using project-based vouchers to help develop or preserve mixed-income housing and supportive housing. Creation of a consortium with a single funding contract would also eliminate the administrative work required when a voucher holder moves from one community to another.

In July 2014, HUD proposed revising its consortia rule to allow all agencies in a consortium to have a single voucher funding contract with HUD, but it hasn’t finalized the rule. Last year, HUD announced a plan to solicit further comment on voucher consortia as part of a new proposed rule streamlining the requirements for forming consortia to manage public housing.[27] But to date, HUD has not begun the formal process to issue such a combined rule, and there is no reliable indication if or when HUD would make this policy change.

Given HUD’s inaction, and the likely delays that will inevitably result from the upcoming change in presidential administrations, Congress could expedite this important policy improvement by requiring HUD to allow consortia of HCV programs to have a single funding contract with HUD, and to implement this policy change by notice.

Congress (or HUD) could further improve consortia policy by allowing PHAs to choose to form partial consortia to operate particular initiatives, such as promoting moves to higher-opportunity areas and using savings created by eliminating the costs of portability billing and paperwork exchanges to increase landlord outreach and provide other housing search assistance. A partial consortium recognized by HUD could also enable PHAs to collaborate efficiently to operate a regional project-based voucher program with a regional waiting list at much lower cost than they could do under a cooperative agreement.

At least initially, many PHAs are likely to be more willing to enter into partial consortia than consortia with a single funding contract, because it will be less challenging to agree on how to operate a single joint project than to merge much of their individual HCV programs’ administration, and because political resistance is likely to be substantially less. As PHAs deepen their collaboration through partial consortia and political resistance diminishes, the administrative efficiencies of a single funding contract may outweigh concerns about losing control, resulting in the expansion over time in the number of PHAs that are willing to make the more dramatic change of forming consortia with single funding contracts.

Federal law broadly permits PHAs to form consortia unless state laws stand in the way. In most states, the laws governing the powers and jurisdiction of PHAs appear to permit consortia but these laws are often unclear, inconsistent, or confusing and they have sometimes been interpreted restrictively by state attorneys general or others.[28]

To avoid any confusion, Congress and HUD should explicitly prevent state laws from blocking formation of consortia. HUD’s final consortia regulation should include the express preemption language for tenant-based programs that exists in federal law.[29]

Congress could also revise the consortia section of the U.S. Housing Act[30] to include a broad preemption provision for both Housing Choice Vouchers and public housing, modeled on (but expanding) Congress’ existing preemption of state law for purposes of administering tenant-based Section 8. If Congress broadened the preemption language in the statute to apply to the administration of housing programs more generally, it could better enable PHAs to form consortia despite any uncertainty as to a state’s interpretation of its joint powers statute or other enabling laws.

HUD has authority under existing statutes and regulations to take over administration of programs that are in substantial default or are “troubled” under HUD’s performance assessment rules and fail to improve satisfactorily within two years. HUD is also empowered to consolidate the poorly performing agency with a willing, well-managed PHA or to appoint another PHA or private management entity to manage the agency’s programs.[31] An authoritative study found that, as of mid-2004, HUD had largely not implemented the substantial new authority and responsibility the 1998 Housing Act provided to address failed management, though HUD did focus reform efforts on several of the largest severely troubled agencies.[32] Congress could direct HUD to both strengthen its performance assessment tools and use available remedies for poor performance to foster the formation of larger, more effective and more efficient local programs, where appropriate. It is important to note that H.R. 4816, discussed below, would bar HUD from using its existing remedial authority to consolidate troubled small agencies with others, or to install new management in such agencies.

As noted above, current law requires — and HUD’s recent study of the cost of administering a high-performing HCV program recommends — paying additional fees for smaller agencies. The study also recommends paying 20 percent more when a family moves with a voucher using portability procedures. This would compensate PHAs in the destination communities for the full cost of administering families’ vouchers on an ongoing basis (rather than paying them 80 percent of the fee) while continuing to allow the PHAs that issued the vouchers to be paid 20 percent of the fee for their initial costs and the time involved in transferring HUD funds. [33]

In the upcoming revision of the administrative fee policy, HUD could substantially limit such additional costs and remove the financial disincentive for PHAs to form consortia or consolidate by paying all except isolated PHAs no more than the amount needed for operating a program of efficient size. If a PHA is the sole HCV administrator in a metro area or non-metro county, making it impractical to join with another PHA to operate more cost-effectively, a size adjustment would make sense. Otherwise, if local communities want to maintain their separate small PHAs despite their higher operating costs and the availability of feasible alternatives, they could supplement the federal payments. With a portion of the money saved from discontinuing or reducing the bonus paid to small agencies, HUD should help PHAs meet the transition costs of forming a consortium or consolidating.

It is important to fairly compensate agencies for their actual, higher net costs of administering vouchers under portability procedures to make them more willing to assist families to use their vouchers in higher-opportunity areas. Current policy does not do this, so if the administrative fee policy is not changed in the coming year to recognize the additional costs due to portability, Congress could add that modification to current policy. These additional costs would be substantially lower, however, if PHAs operating within a metro area formed consortia (or consolidated), enabling families to move within the expanded area of operations without having to use portability procedures.

Congress should direct HUD to pay the same (or more similar) fees to housing agencies regardless of size, though it could continue paying higher fees to small agencies that are so isolated they do not have a real opportunity to form consortia or consolidate. In addition, Congress should direct HUD to use part of the savings from scaling back added fees for small agencies for technical assistance and one-time grants to help PHAs meet the transition costs of forming a consortium or consolidating. In addition, Congress could require any new administrative fee policy to “pay for success” by rewarding PHAs that increase the number of families using vouchers in low-poverty, higher opportunity areas.

H.R. 4816, The Small Public Housing Agency Opportunity Act (SPHAOA), introduced by Representative Steve Palazzo (R-MS),[34] is intended to reduce administrative burdens for small local agencies that operate the federal public housing and Housing Choice Voucher programs. Unfortunately, the bill’s deregulation provisions go so far to sweep aside federal rules and safeguards that they could have unintended and undesirable consequences — such as higher federal costs, fewer low-income families receiving federal housing assistance, and higher rents for many vulnerable households. They would also complicate program administration by establishing a separate set of rules for small agencies, and create a disincentive for agencies to form consortia or consolidate.

Policymakers have already done much in recent years to streamline rental assistance, including enacting a broad set of reforms in the Housing Opportunity Through Modernization Act (HOTMA) in July 2016. These recent measures will substantially reduce administrative costs through careful changes that apply to all agencies regardless of size and they balance streamlining against other goals, such as ensuring effective assistance to low-income families and efficient use of federal funds.

HUD is also evaluating alternative policies that go beyond recently enacted reforms. For example, as directed by Congress, HUD is conducting a rent reform demonstration testing whether alternative formulas for setting tenant rents can ease administrative burdens and support work. In addition, in December 2015, Congress directed HUD to add 100 agencies — nearly all of them small or mid-sized — to its Moving to Work (MTW) demonstration. This expansion will provide broad flexibility to test alternative policies and, in a departure from prior practice under MTW, requires that those policies be carefully evaluated.

HUD should move promptly to implement HOTMA and ensure that MTW expansion generates findings that are rigorous and useful. Until the recent streamlining measures have been assessed and the ongoing and planned demonstration evaluations completed, there is no justification for Congress to consider sweeping additional deregulation like that proposed in SPHAOA.

Rather than weakening standards for small housing agencies, Congress and HUD should help and encourage them to work together with other agencies to achieve economies of scale and administer assistance more effectively. SPHAOA seeks to advance this goal by allowing agencies that administer rental assistance jointly through a consortium to combine reports to HUD. Consortia are a potentially powerful tool for easing administrative and oversight burdens and improving program performance. But realizing their potential will require HUD and Congress to take the steps outlined above, and not just streamline reporting requirements as SPHAOA proposes.[35]

The Committee has requested witnesses’ views about a discussion draft of the “Fostering Stable Housing Opportunities Act of 2016,” circulated by Rep. Turner. The draft bill is well-intentioned, aiming to alleviate the serious problem of many youth aging out of foster care becoming homeless. The proposed approach, however, is unwise.

Nearly two decades ago, in the Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act of 1998, Congress rescinded federal preferences for homeless applicants and other types of households that previous Congresses had deemed a priority for admission. In their place, the 1998 Act imposed a simple-to-administer requirement that local agencies and owners admit extremely low-income applicants for a specified share of available units or vouchers each year (the percentage and related requirements vary by program). Such income-targeting requirements achieve the key goal of ensuring that a large share of federal housing resources serve those with the greatest needs, while deferring to state and local agencies to determine whether it is worth the administrative burden to prioritize for admission certain types of households, and if so, which types of households they consider most important to assist more quickly. It would be unwise to tamper with this long-standing policy compromise that effectively balances federal and state/local concerns.

Underlying the disturbing problem of homelessness among youth aging out of foster care are a shortage of housing subsidies — only one out of four eligible households receives federal assistance — and a foster care system that terminates support without taking all feasible steps to enable young adults to live in stable housing and otherwise meet their basic needs. Congress and the states should address these serious problems, which will require new resources, rather than assuming that the challenges faced by foster youth can be addressed merely by requiring them to go to the front of years’ long waiting lists for housing assistance. Indeed, Congress has taken steps recently to provide additional housing resources and income-promoting services for youth aging out of foster care, and the Senate’s 2017 HUD appropriations bill would add funds for this purpose. More could and should be done, but this draft bill is not a sound approach.