- Home

- Balancing State Flexibility Without Weak...

Balancing State Flexibility Without Weakening SNAP’s Success

Testimony of Stacy Dean, Vice President for Food Assistance Policy,

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities,

Before the House Committee on Agriculture

U.S. House of Representatives

Thank you for the opportunity to testify today. I am Stacy Dean, Vice President for Food Assistance Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, an independent, non-profit, nonpartisan policy institute located here in Washington. The Center conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting low- and moderate-income families. The Center’s food assistance work focuses on improving the effectiveness of the major federal nutrition programs, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). I have worked on SNAP policy and operations for more than 20 years. Much of my work is providing technical assistance to state officials who wish to explore options and policy to improve their program operations in order to more efficiently serve eligible households. I also lead our work on program integration and efforts to facilitate and streamline low-income people’s enrollment into the package of benefits for which they are eligible. This work has included directing technical assistance to state officials through the Work Support Strategies Initiative run by the Urban Institute and the Center for Law and Social Policy. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities receives no government funding.

My testimony today is divided into two sections: 1) SNAP’s role in our country as a federal nutrition program; and 2) an overview of state flexibility and options in SNAP.

SNAP Plays a Critical Role in Our Country

Before turning to today’s hearing topic of SNAP’s state options and flexibility, I think it is important to review some of SNAP’s most critical features. The program is a highly effective anti-hunger program that is administered with relatively low overhead and a high degree of accuracy. Much of the program’s success is due to a consistent national benefit structure, rigorous requirements on states and clients to ensure a high degree of program integrity and a focus on providing food assistance. Congress and USDA have sought to provide states flexibility where it would enhance the program and without weakening SNAP’s success.

As of November of last year, SNAP was helping more than 45 million low-income Americans to afford a nutritionally adequate diet by providing them with benefits via a debit card that can be used only to purchase food. On average, SNAP recipients receive about $1.41 per person per meal in food benefits. One in seven Americans is participating in SNAP — a figure that speaks both to the extensive need across our country and to SNAP’s important role in addressing it.

Policymakers created SNAP to help low-income families and individuals purchase an adequate diet. It does an admirable job of providing poor households with basic nutritional support and has largely eliminated severe hunger and malnutrition in the United States.

When the program was first established, hunger and malnutrition were much more serious problems in this country than they are today. A team of Field Foundation-sponsored doctors who examined hunger and malnutrition among poor children in the South, Appalachia, and other very poor areas in 1967 (before the Food Stamp Program was widespread in these areas) and again in the late 1970s (after the program had been instituted nationwide) found marked reductions over this ten-year period in serious nutrition-related problems among children. The doctors gave primary credit for this reduction to the Food Stamp Program (as the program was then named). Findings such as this led then-Senator Robert Dole to describe the Food Stamp Program as the most important advance in the nation’s social programs since the creation of Social Security.

Consistent with its original purpose, SNAP continues to provide a basic nutrition benefit to low-income families, elderly, and people with disabilities who cannot afford an adequate diet. In some ways, particularly in its administration, today’s program is stronger than at any previous point. By taking advantage of modern technology and business practices, SNAP has become substantially more efficient, accurate, and effective. While many low-income Americans continue to struggle, this would be a very different country without SNAP.

SNAP Protects Families From Hardship and Hunger

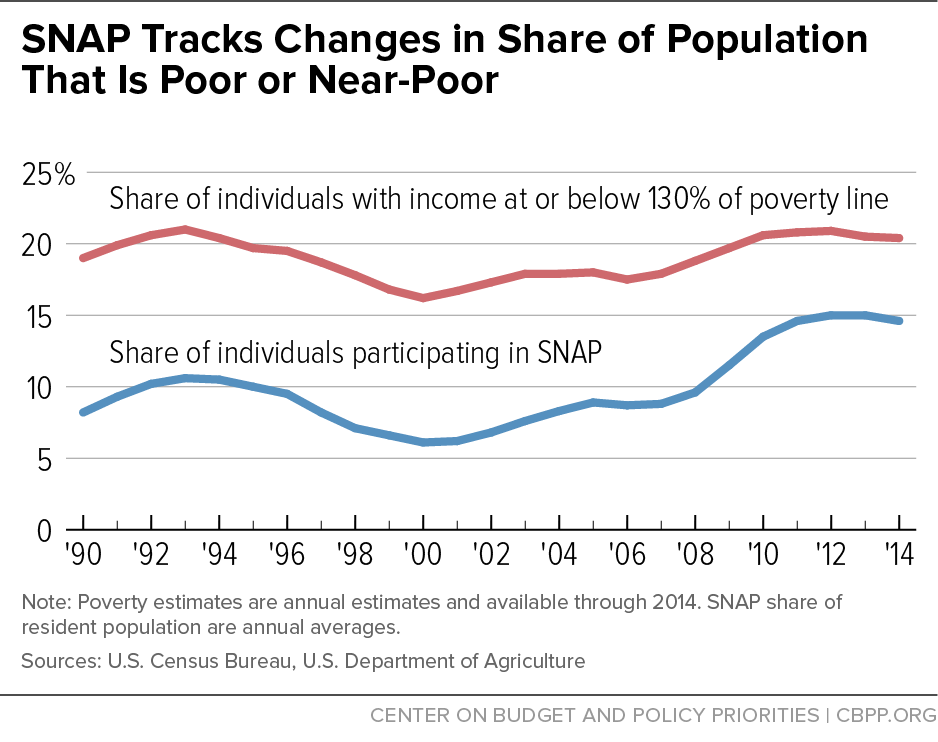

SNAP benefits are an entitlement, which means that anyone who qualifies under the program’s rules can receive benefits. This is the program’s most powerful feature; it enables SNAP to respond quickly and effectively to support low-income families and communities during times of economic downturn and increased need. Enrollment expands when the economy weakens and contracts when the economy recovers. (See Figure 1.)

As a result, SNAP can respond immediately to help families and to bridge temporary periods of unemployment or a family crisis. A U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) study of SNAP participation over the late 2000’s found that slightly more than half of all new entrants to SNAP participated for less than one year and then left the program when their immediate need passed.

SNAP’s ability to serve as an automatic responder is also important when natural disasters strike. States can provide emergency SNAP within a matter of days to help disaster victims purchase food. In 2014 and 2015, for example, it helped households in the Southeast affected by severe storms and flooding and households on the west coast affected by wildfires.

SNAP’s caseloads grew in recent years primarily because more households qualified for SNAP because of the recession, and because more eligible households applied for help. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has confirmed that “the primary reason for the increase in the number of participants was the deep recession . . . and subsequent slow recovery; there were no significant legislative expansions of eligibility.”[1]

While this increase in participation and spending was substantial, SNAP participation and spending have begun to decline as the economic recovery has begun to reach low-income SNAP participants. In 2014 and 2015 SNAP caseloads declined in most states; as a result, the national SNAP caseload fell by 2 percent both years. Nationally, for more than two years fewer people have participated in SNAP each month than in the same month of the prior year; about 2.5 million fewer people participated in SNAP in recent months than in December 2012, when participation peaked.

As a result of this caseload decline, spending on SNAP as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell by 4 percent in 2015. In 2014 it fell by 11 percent, largely due to the expiration of the Recovery Act’s SNAP benefit increase. CBO predicts that this trend will continue, and that SNAP spending as a share of GDP will fall to its 1995 levels by 2020.

SNAP Lessens the Extent and Severity of Poverty and Unemployment

SNAP targets benefits on those most in need and least able to afford an adequate diet. Its benefit formula considers a household’s income level as well as its essential expenses, such as rent, medicine, and child care. Although a family’s total income is the most important factor affecting its ability to purchase food, it is not the only factor. For example, a family spending two-thirds of its income on rent and utilities will have less money to buy food than a family that has the same income but lives in public or subsidized housing.

While the targeting of benefits adds some complexity to the program and is an area where states sometimes seek to simplify, it helps ensure that SNAP provides the most assistance to the poorest families with the greatest needs.

This makes SNAP a powerful tool in fighting poverty. A CBPP analysis using the government’s Supplemental Poverty Measure, which counts SNAP as income, and that corrects for underreporting of public benefits in survey data, found that SNAP kept 10.3 million people out of poverty in 2012, including 4.9 million children. SNAP lifted 2.1 million children above 50 percent of the poverty line in 2012, more than any other benefit program.

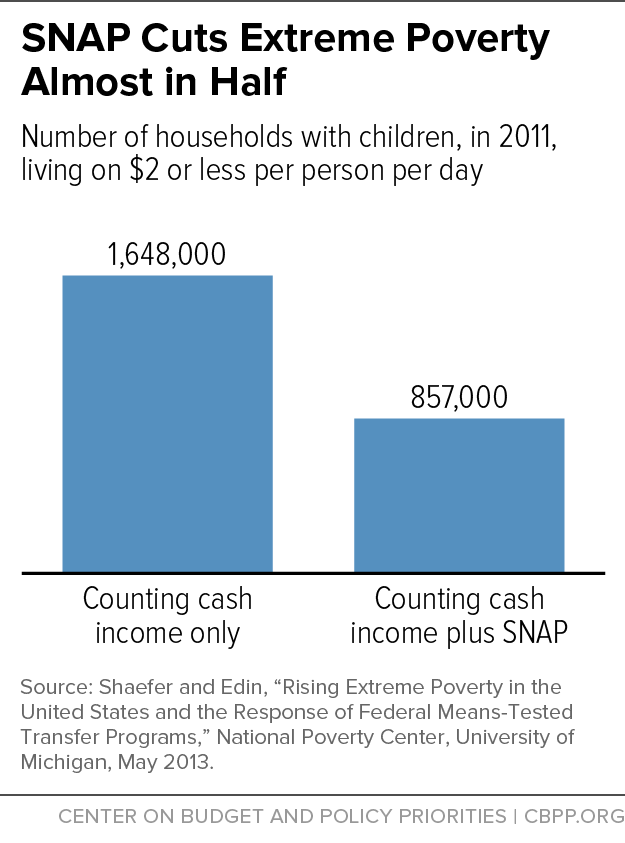

SNAP is also effective in reducing extreme poverty. A recent study by the National Poverty Center estimated the number of U.S. households living on less than $2 per person per day, a classification of poverty that the World Bank uses for developing nations. The study found that counting SNAP benefits as income cut the number of extremely poor households in 2011 by nearly half (from 1.6 million to 857,000) (see Figure 2) and cut the number of extremely poor children by more than half (from 3.6 million to 1.2 million).

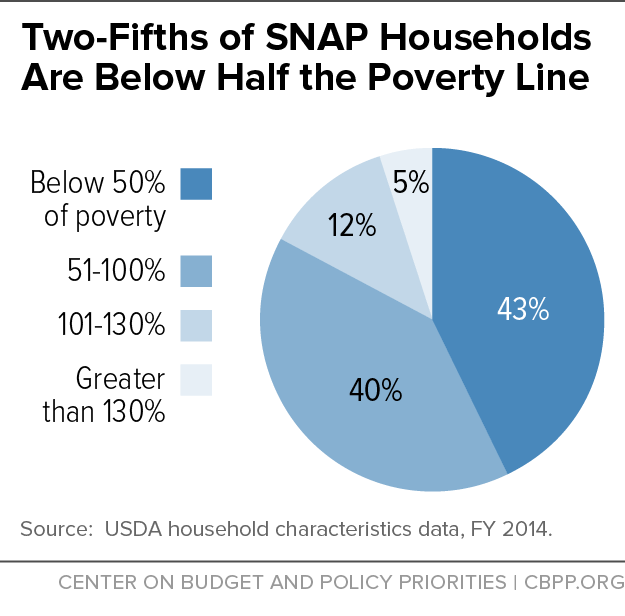

SNAP is able to achieve these results because it is so targeted at very low-income households. Roughly 93 percent of SNAP benefits goes to households with incomes below the poverty line, and 58 percent goes to households with incomes below half of the poverty line (about $10,045 for a family of three in 2016). (See Figure 3.)

During the deep recession and still-incomplete recovery, SNAP has become increasingly valuable for the long-term unemployed as it is one of the few resources available for jobless workers who have exhausted their unemployment benefits. Long-term unemployment hit record highs in the recession and remains unusually high; in January 2016, more than a quarter (26.9 percent) of the nation’s 7.8 million unemployed workers had been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. That’s much higher than it’s ever been (in data back to 1948) when overall unemployment has been so low.

SNAP also protects the economy as a whole by helping to maintain overall demand for food during slow economic periods. In fact, SNAP benefits are one of the fastest, most effective forms of economic stimulus because they get money into the economy quickly. Moody’s Analytics estimates that in a weak economy, every $1 increase in SNAP benefits generates about $1.70 in economic activity (i.e. increase in economic activity and employment per budgetary dollar spent) among a broad range of policies for stimulating economic growth and creating jobs in a weak economy.

SNAP Improves Long-term Health and Self-sufficiency

While reducing hunger and food insecurity and lifting millions out of poverty in the short run, SNAP also brings important long-run benefits.

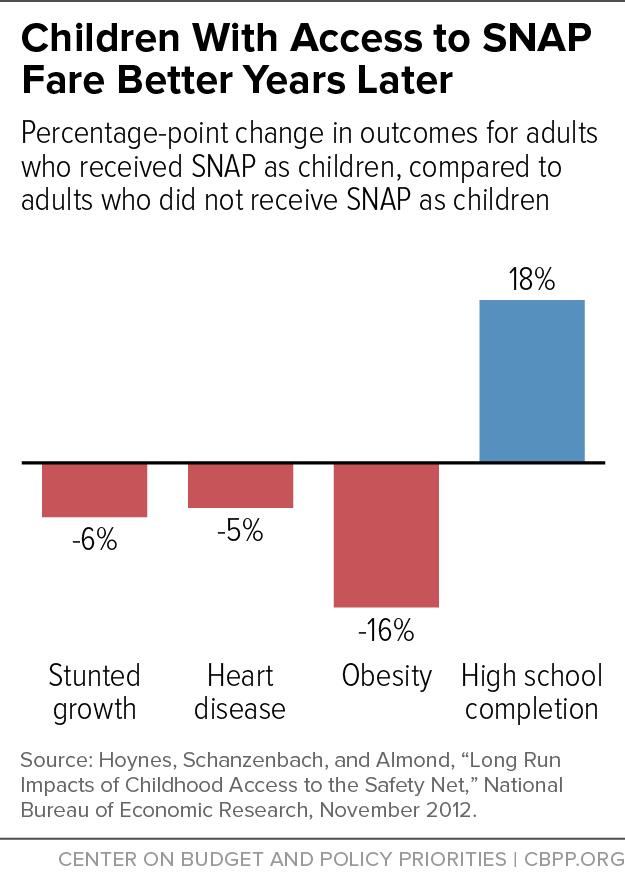

A recent National Bureau of Economic Research study examined what happened when government introduced food stamps in the 1960s and early 1970s and concluded that children who had access to food stamps in early childhood and whose mothers had access during their pregnancy had better health outcomes as adults years later, compared with children born at the same time in counties that had not yet implemented the program. Along with lower rates of “metabolic syndrome” (obesity, high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes), adults who had access to food stamps as young children reported better health, and women who had access to food stamps as young children reported improved economic self-sufficiency (as measured by employment, income, poverty status, high school graduation, and program participation).[2] (See Figure 4.)

Supporting and Encouraging Work

In addition to acting as a safety net for people who are elderly, disabled, or temporarily unemployed, SNAP is designed to supplement the wages of low-income workers.

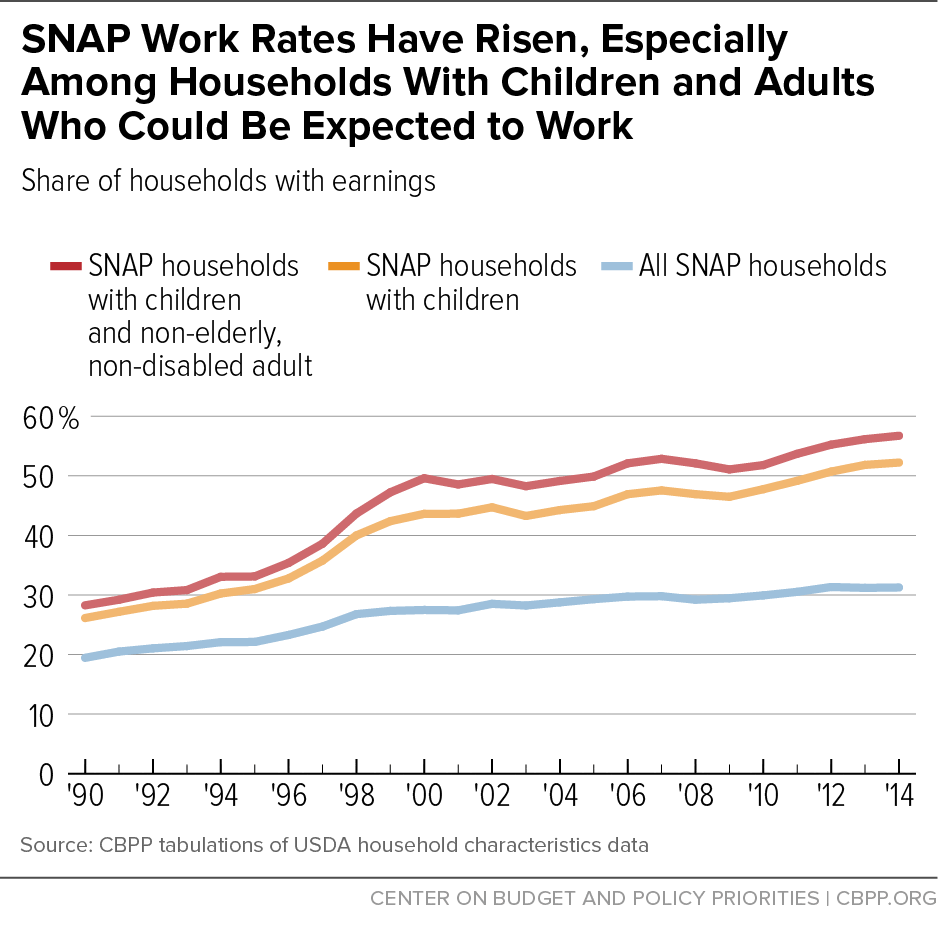

The number of SNAP households that have earnings while participating in SNAP has more than tripled — from about 2 million in 2000 to about 7 million in 2014. The share of SNAP families that are working while receiving SNAP assistance has also been rising — while only about 28 percent of SNAP families with an able-bodied adult had earnings in 1990, 57 percent of those families were working in 2014. (See Figure 5.)

The SNAP benefit formula contains an important work incentive. For every additional dollar a SNAP recipient earns, her benefits decline by only 24 to 36 cents — much less than in most other programs. Families that receive SNAP thus have a strong incentive to work longer hours or to search for better-paying employment. States further support work through the SNAP Employment and Training program, which funds training and work activities for unemployed adults who receive SNAP.

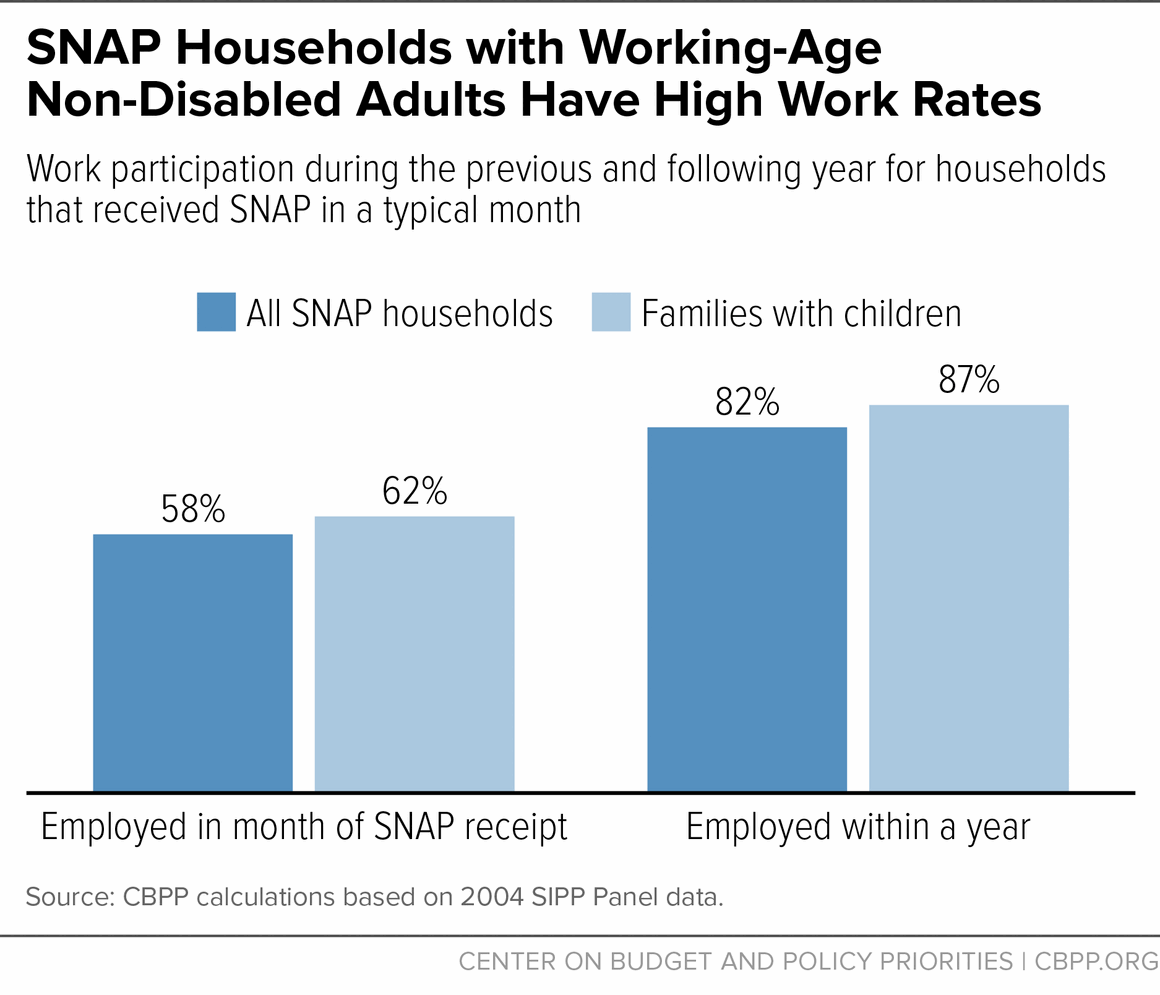

Most SNAP recipients who can work do so. Among SNAP households with at least one working-age, non-disabled adult, more than half work while receiving SNAP — and more than 80 percent work in the year prior to or the year after receiving SNAP. The rates are even higher for families with children. (See Figure 6.) (About two-thirds of SNAP recipients are not expected to work, primarily because they are children, elderly, or disabled.)

Strong Program Integrity

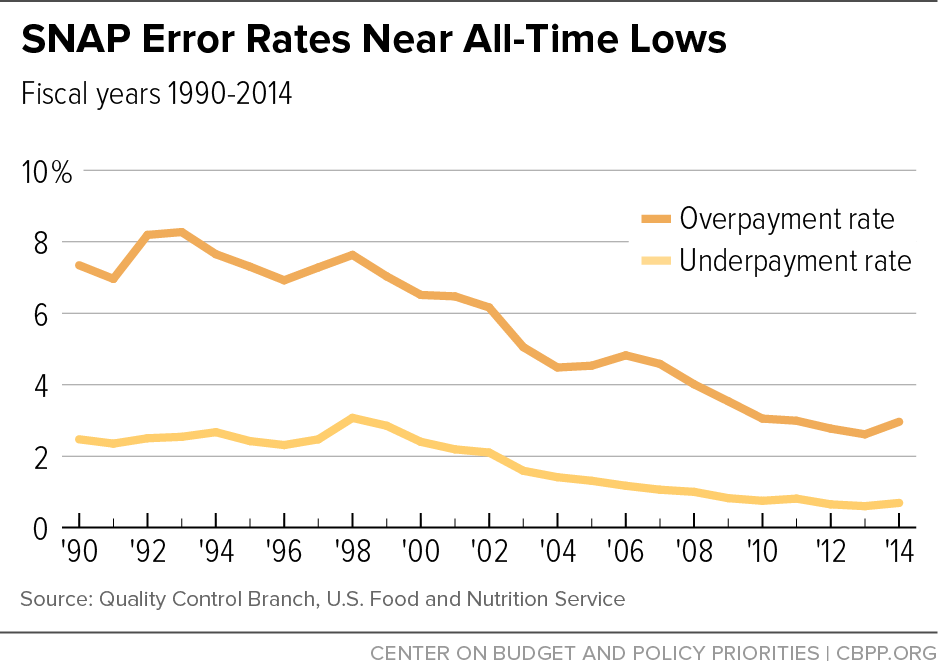

SNAP has one of the most rigorous payment error measurement systems of any public benefit program. Each year states take a representative sample of SNAP cases (totaling about 50,000 cases nationally) and thoroughly review the accuracy of their eligibility and benefit decisions. Federal officials re-review a subsample of the cases to ensure accuracy in the error rates. States are subject to fiscal penalties if their error rates are persistently higher than the national average.

The percentage of SNAP benefit dollars issued to ineligible households or to eligible households in excessive amounts fell for seven consecutive years and stayed low in 2014 at 2.96 percent, USDA data show. The underpayment error rate also stayed low at 0.69 percent. The combined payment error rate — that is, the sum of the overpayment and underpayment error rates — was 3.66 percent, low by historical standards.[3] Less than 1 percent of SNAP benefits go to households that are ineligible. (See Figure 7.)

If one subtracts underpayments (which reduce federal costs) from overpayments, the net loss to the government last year from errors was 2.27 percent of benefits.

In comparison, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) estimates a tax noncompliance rate of 16.9 percent in 2006 (the most recently studied year). This represents a $450 billion loss to the federal government in one year. Underreporting of business income alone cost the federal government $122 billion in 2006, and small businesses report less than half of their income.[4]

The overwhelming majority of SNAP errors that do occur result from mistakes by recipients, eligibility workers, data entry clerks, or computer programmers, not dishonesty or fraud by recipients. In addition, states have reported that almost 60 percent of the dollar value of overpayments and almost 90 percent of the dollar value of underpayments were their fault, rather than recipients’ fault. Much of the rest of overpayments resulted from innocent errors by households facing a program with complex rules.

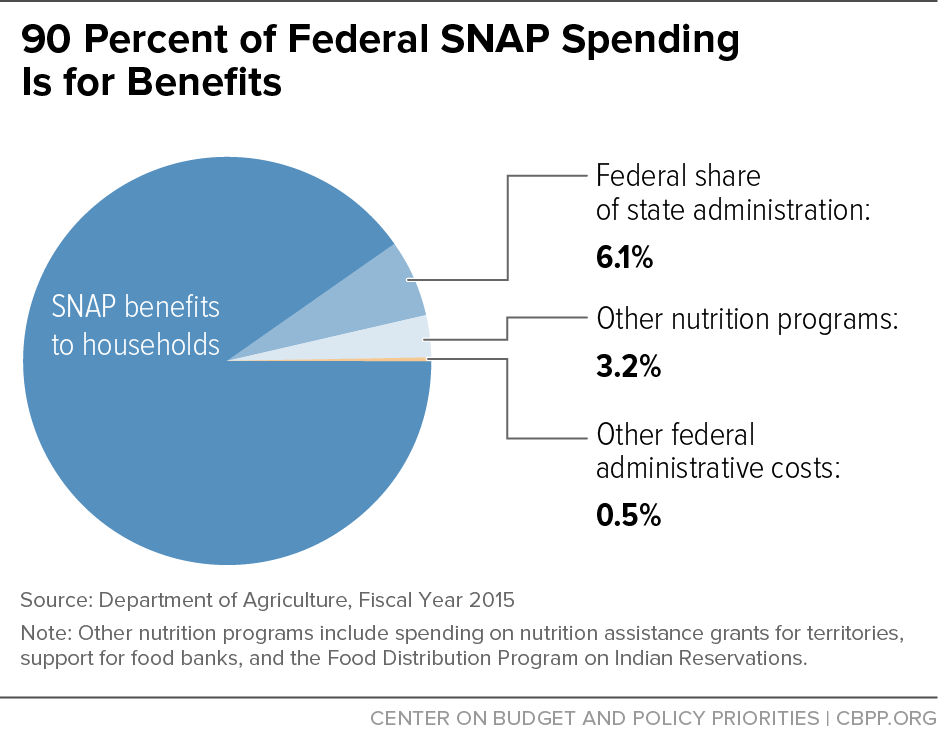

Finally, SNAP has low administrative overhead. About 90 percent of federal SNAP spending goes to providing benefits to households for purchasing food. Of the remaining 10 percent, about 7 percent was used for state and federal administrative costs, including eligibility determinations, employment and training and nutrition education for SNAP households, and anti-fraud activities. About 3 percent went for other food assistance programs, such as the block grant for food assistance in Puerto Rico and American Samoa, commodity purchases for the Emergency Food Assistance Program (which helps food pantries and soup kitchens across the country), and commodities for the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations.

Balancing State Flexibility With Effective National Standards

While SNAP is a national program with relatively uniform eligibility standards and basic parameters for program administration and program integrity, it is administered by states, which share in the costs of administering the program. States are a key partner in the program’s success and one of their primary considerations is that they do not administer SNAP in a vacuum or under a consistent set of local circumstances. All states have integrated SNAP into their broader health and/or human service systems for both efficiency and service considerations. In most places, SNAP is co-administered with many other programs.

While Medicaid is the program with the most significant overlap with SNAP (about three-quarters of households receiving SNAP benefits in 2014 had at least one member receiving health coverage through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program),[5] states also co-administer SNAP with other programs including child care, cash assistance, and refugee assistance. That means that they often are using the same set of staff, computer systems, local offices, and forms for many different programs. States are constantly working to integrate the major safety net programs into a coherent package for families, in order to support their stability while improving efficiency and program integrity.

As a result, the program provides states with flexibility in how they operate the program to respond to local circumstances, particularly with respect to harmonizing SNAP operations with Medicaid and other local programs.

In other cases, states have identified program rules that conflict with the program’s core goals. One of the key examples of this was in the late 1990’s after the passage of the 1996 welfare reform law. As many low-income families with children were leaving cash assistance as a result of policy changes to that program and the booming economy, states also saw a drop-off in food stamp enrollment that could not be explained by a drop in the share of eligible individuals. Many families were leaving cash assistance for work but were not earning wages that would disqualify them from SNAP. States began to see that some of SNAP’s eligibility and administrative requirements were undermining their ability to serve working-poor families. As a result, Congress enacted numerous new state options in the 2002 and 2008 Farm Bills designed to allow states to improve service to working families.

And, states often have ideas for ways to improve program administration or design that were not envisioned by Congress or USDA and that merit accommodation or testing. In many cases, the program allows for local customization. When flexibility is not explicitly provided, USDA has the authority to waive its SNAP requirements when it believes the requested change would be in the program’s best interest. Typically, USDA is cautious about allowing unproven sweeping new changes into the program. The department often seeks early innovators to test ideas and then identifies the best means to integrate (or reject) the ideas as state options.

Congress and USDA have had to weigh states’ and localities’ requests for flexibility with other core values and considerations, most notably:

- At its core, SNAP is a food assistance program. How it assesses what comprises a household, and a household’s ability to purchase food, is necessarily different than how we might measure the same group of people’s obligation and ability to provide for each other’s health care or child care.

- SNAP is a national program meant to respond as consistently as possible to the needs of low-income people and families who cannot afford a basic diet no matter where they live. Currently, families with the same economic circumstances in two states can expect the same level of SNAP benefits under this national framework. The same is not true of many state-operated human services and income support programs. In fact, SNAP plays a key role in leveling out the disparate level of wages and support available to poor families and individuals across states.

- The program is a highly effective intervention that protects vulnerable families, seniors, people with disabilities, and others from hunger and hardship. Flexibility and state variation must be carefully considered as to whether it will augment the program’s ability to meet these basic needs or put needy people at greater risk.

- SNAP benefits are paid entirely by the federal government. Federal SNAP rules require the highest level of rigor of any major benefit program; with respect to assessing eligibility and determining benefit levels to ensure that states are properly administering federal funds. And, SNAP rules generally require a detailed assessment of a household’s current financial situation. Few other programs operated by states meet these standards.

- A consistent framework for customer service standards, such as the requirements for states to process applications within 30 days of receipt and for households to provide documentation of their income and circumstances, is important to ensure a shared sense of program requirements across states. Early experience with the program demonstrated that states were extremely uneven in how they operated the program and, in some cases, access was extremely limited.

There can be a tension between remaining true to SNAP’s goals of addressing food insecurity and hunger and providing states with flexibility to set SNAP policy. While the discussion and debate around the appropriate level of state flexibility is an ongoing one, I believe that Congress and USDA have struck a reasonable balance in maintaining SNAP as a high performing national program while according states sufficient flexibility. The program has valued maintaining a generally consistent national eligibility and benefit structure that demands a high level of rigor and integrity when assessing eligibility, as well as a common framework of what’s expected of clients and states in administering the program. Flexibility has been provided in a number of areas detailed in the section below.

As you assess suggestions for further flexibility or modifications to the program, we encourage you to ensure that those proposals do not undermine SNAP’s strengths as a food assistance program targeted to individuals and families with the least ability to purchase food. Proposals to sweep away some of SNAP’s key features or that would shift benefits away from food assistance to other purposes would run counter to the program’s goals and proven success. Block grants, capped funding, or merged funding streams all would eliminate the most important features of SNAP — its national entitlement structure. Any of these types of changes to SNAP’s structure must be avoided.

To be sure, despite the level of flexibility offered in SNAP, it is less flexible than various other programs state-administered health and human services programs. Programs with capped federal funding such as the child care development block grant or the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant offer states more flexibility in setting program rules. Of course, those programs are extremely limited in in their reach and impact. And, programs that states administer that require a significant state financial contribution, such as Medicaid, establish basic minimum federal standards but give states flexibility to expand the program’s eligibility and benefit package as well as tailor administration and operations within more general federal guidelines. Because states also operate these other programs, SNAP can strike them as significantly less flexible by comparison.

Areas of Flexibility in SNAP

SNAP’s statute, regulations, and waivers provide state agencies with various policy options. State agencies use this flexibility to adapt their programs to meet the needs of their eligible, low‐income residents. Certain options may facilitate program design goals, such as removing or reducing barriers to access for low‐income families and individuals, or providing better support for those working or looking for work. Others focus on streamlining and coordinating SNAP with other programs, such as Medicaid. This flexibility helps states better target benefits to those most in need, streamline program administration and field operations, and coordinate SNAP activities with those of other programs.

The following are several categories of flexibility within the program, with examples of the types of flexibility available in each category. The list is meant to provide a flavor of the available options versus providing an exhaustive catalogue within each category.

Options that Provide Flexibility in Eligibility or Benefit Calculation Policy

As a part of and since the passage of the 1996 welfare law, Congress has offered states several options to adopt less restrictive eligibility and benefit calculation rules in SNAP in order to coordinate SNAP with other programs, such as TANF cash assistance and Medicaid. In addition, this flexibility has made it much easier for states to serve working families.

- Vehicle asset test: Federal rules for counting the value of cars and other vehicles toward SNAP eligibility are restrictive and outdated. The Food Stamp Act of 1977 required states to count the fair market value of a car as a resource to the extent that it exceeded $4,500, an amount not indexed to inflation that has been raised by only $150 in almost 40 years. Because federal policy was viewed as preventing low-income households, especially working families, from owning reliable means of transportation, and because many states had addressed this concern in other programs for which they set eligibility rules, in 2000 Congress gave states flexibility to craft a food stamp vehicle asset rule that suits their needs. Instead of the federal rules, states may use in SNAP the method for valuing vehicles that the state has established under a TANF-funded cash or non-cash assistance program so long as it is not more restrictive than federal food stamp rules. After this change, many states imported into SNAP the vehicle rules they used in their TANF cash assistance or TANF-funded child care programs. Within a few years of the change, every state had modified its rules for counting the value of vehicles so that participants could own a more reliable car.

-

Categorical eligibility: The 1996 welfare law provided states with an option to align two aspects of SNAP eligibility rules — the gross income eligibility limit and the asset test — with the eligibility rules they use in programs financed under their TANF block grant. Over 40 states have adopted this option to simplify their programs, reduce administrative costs, and broaden SNAP eligibility to certain families in need, primarily low-wage working families.

States use the categorical eligibility option to enable households with gross incomes modestly above 130 percent of the poverty line (up to 200 percent of poverty in a few states) but disposable income below the poverty line — or with savings modestly above $2,250 (an asset limit that has declined by about 50 percent in real, i.e., inflation-adjusted, terms since 1986) — to qualify for SNAP assistance in recognition of their need.

In states that take the option, households must still apply through the regular application process, which has rigorous procedures for documenting applicants’ income and circumstances. But the option allows states to provide SNAP to certain working families with children or to households that have built a modest amount of savings who otherwise would not qualify for help affording food.

- Flexibility with the gross income limit favors low-income households with modest incomes and high living expenses. About $9 of every $10 in SNAP benefits that are provided to low-income households who qualify for SNAP because their state uses this option are provided to low-income working households. About $8 of every $10 in such benefits go to families with children. About two-thirds of these benefits go to households with gross income below 150 percent of the federal poverty line.

- Without this option, states cannot provide SNAP to poor families who have managed to save as little as $2,251 or to seniors or people with disabilities who have saved as little as $3,251. Building assets helps low-income households invest in their future, avert a financial crisis that can push them deeper into poverty or even lead them to become homeless, avoid accumulating debt that can impede economic mobility, and have a better chance of avoiding poverty and greater reliance on government in old age.

- Despite some claims, categorical eligibility was not the major driver of increased caseloads during the recent economic downturn. The economy and increased poverty as well as a rise in the participation rate among eligible people were the overwhelming drivers of caseload increases during the recession. Economists Peter Ganong and Jeffrey Liebman found that increased adoption of broad-based categorical eligibility accounted for 8 percent of the caseload increase. (Because households eligible as a result of broad-based categorical eligibility receive lower-than-average benefits, this change accounted for a smaller share of the cost increase during the same period.)[6]

- Transitional benefits: A change in the 2002 Farm Bill allows states to provide up to five months of transitional SNAP benefits to families that leave states’ TANF cash assistance programs. The provision was enacted in response to research that found that fewer than half of households that left TANF cash assistance stayed connected to SNAP, despite earning low wages and (in most cases) remaining eligible for SNAP benefits. The option allows states to continue a family’s SNAP benefits when a family gains a job and leaves TANF cash assistance, based on information the state already has and without requiring the family to reapply or submit additional paperwork at that time. The continuity of SNAP can reward work and help make clear to families that SNAP is available to low-income families that do not receive cash assistance. Helping families retain benefits can help make the transition to work more successful and ensure that families are better off working than on welfare. In 2013, 20 states had adopted the option.

- Simplified income and resources: Two other provisions of the 2002 farm bill allowed states to simplify which income and resources count toward SNAP eligibility by excluding uncommon forms of income and/or resources that they exclude in their TANF cash assistance or Medicaid programs. More than half the states have taken advantage of the option to exclude such income or resources. The change has allowed states to simplify forms and reduce the administrative burdens of tracking down and verifying these obscure forms of income or assets.

State Options Within SNAP’s Three-Month Time Limit

Able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWDs) are limited to three months of SNAP in any three-year period unless they are working at least half time, participating in a qualifying job training activities for an average of 20 hours a week, or doing workfare. States and localities are not required to help the affected people find jobs or provide a place in a job training program that would allow them to keep benefits. Very few do so, leaving it to the participants to find enough work or training to keep their benefits. As a result, states’ first choice within the time limit policy is whether to operate the rule as a work requirement — whereby they provide work slots to those willing to work — or as a time limit where they cut off individuals after three months regardless of their willingness to work and whether they are searching for a job. Most elect to operate the rule as a time limit.

As a result, the three-month time limit for childless, non-disabled adults who are unable to find 20 hours a week of work is one of the harshest provisions in SNAP. By 2000, three years after it was first implemented, an estimated 900,000 individuals had lost benefits. Since the time limit has been in effect, it has severely restricted this group’s access to the program.[7] Many of those who have lost benefits have faced serious hardship and have not been eligible for other kinds of public assistance.

In addition to the choice of whether to operate the rule as a time limit or a work requirement, states have two main options within this program rule:

-

Waivers for areas with sustained levels of relatively high unemployment. The authors of the provision in 1996, Reps. Kasich and Ney, included some modest state flexibility related to this provision. States can waive the time limit in areas with high unemployment, meaning that individuals residing in a waived area are not subject to the time limit. States request these waivers by submitting evidence to FNS that areas within the state, such as counties, cities, or tribal reservations, have high and sustained unemployment.

In the past few years, the three-month limit hasn’t been in effect in many states. Many states qualified to waive the time limit throughout the state due to high unemployment rates during and since the Great Recession. But as unemployment rates have fallen, fewer areas are qualifying for statewide waivers (though in most states there are some counties or other localities that remain eligible for waivers because they continue to have high unemployment).

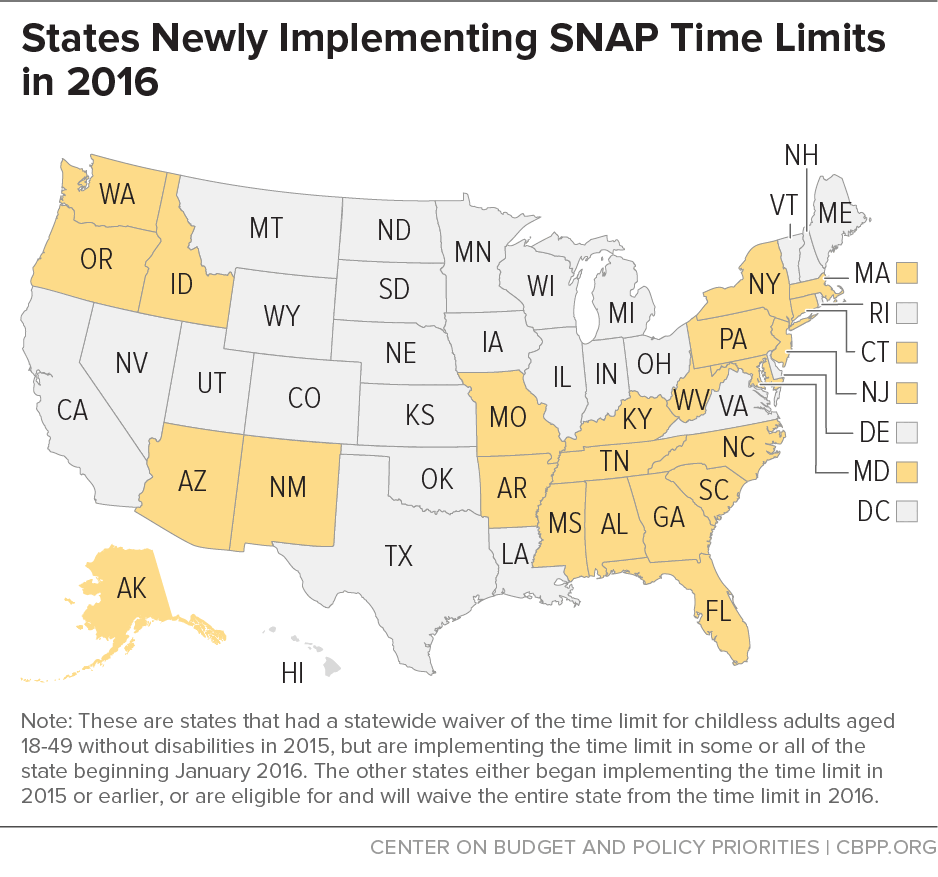

In 2016, the time limit will be in effect in more than 40 states. In 23 states, it will be the first time the time limit has been in effect since before the recession. (See Figure 9.) Of these states, 19 must reimpose the time limit in at least part of the state; another four are electing to reimpose the time limit despite qualifying for a statewide waiver from the time limit because of continued high unemployment.[8]

- Individual exemptions. In addition to the mandated exemptions from the time limit (for example, disability and pregnancy), states have additional flexibility to set their own exemption criteria. Each year, a state can exempt roughly 15 percent of its caseload that is subject to the time limit. Once a year, FNS estimates the number of ABAWDs who are subject to the three-month time limit who are not living in a waived area and calculates exemptions representing 15 percent of that number. Each exemption may be used to exempt one individual for one month, though states can grant continuing exemptions to a single individual to exempt that person for a number of months. Many states find this flexibility difficult to use and do not take advantage of this option at all.

State Options Within Disqualification and Sanction Policy

SNAP gives states flexibility, within federally proscribed parameters, to tailor SNAP’s disqualification and sanction policy for participants’ noncompliance with certain program rules, including work requirements. The 1996 welfare law included several state options to ensure that states could coordinate sanction policy across cash and food assistance and options for additional SNAP-only sanctions.

- State options to conform SNAP sanctions with TANF work rules. The 1996 welfare law included three state options to ensure that SNAP work rules and sanctions complement, rather than undermine, the rules states establish in their TANF cash assistance programs. First, states have the option to disqualify an individual from SNAP if she or he has been disqualified from TANF for failure to comply with TANF work requirements. States also have the option to decrease a household’s SNAP benefits by up to 25 percent when the household’s TANF benefits have been cut due to non-compliance with a TANF work requirement. Finally, states must impose SNAP sanctions on certain TANF households who do not comply with TANF work requirements. States have an option to disqualify SNAP benefits for the entire family for up to six months (unless the family has a child under age 6).

- State options for sanctions for non-compliance with SNAP work requirements. For SNAP households that do not include TANF recipients, the 1996 welfare law also gave states more discretion over penalties for violating SNAP’s various work-related requirements (which are separate and distinct from the three-month time limit that childless adults face.) Under SNAP’s rules, an individual who does not comply with SNAP’s work requirements is ineligible for a designated period of time, with the duration of the sanction increasing with successive offenses. States have options for how many months the disqualification lasts and whether to terminate SNAP for just that individual or the entire household (for up to six months).

- Behavior-related sanctions. States have several state options related to behavior other than work.

- First, for TANF recipients who are sanctioned for violating a TANF requirement related to conduct other than a work requirement (i.e., where a family’s children who are students are required to stay in school or risk losing some of the households’ cash assistance benefit) the household cannot receive increased SNAP benefits because of the TANF benefit cut and states may cut the household’s SNAP benefit by up to 25 percent or import the TANF disqualification into SNAP (for the individual disqualified from TANF).

- States may disqualify from SNAP parents who are not complying with Child Support Enforcement. This includes custodial parents who are not cooperating with states’ efforts to establish the paternity of the child and obtain support payments, and non-custodial parents who are not cooperating or paying child support. States also have the option to sanction non-custodial parents who are in arrears on their child support payments.

- Prohibition on convicted drug felons participating in the program. A provision of the 1996 welfare law permanently disqualifies individuals from SNAP (and TANF) if they are convicted of a state or federal felony related to possession, distribution, or use of controlled substances after August 1996 (the date of enactment of the welfare law). States may pass legislation to opt out of this provision. They also may impose certain conditions on former felons who seek SNAP. For example, a state may require the individual to periodically submit to a drug test. Or a state may opt to impose the ban on people whose offense was selling (rather than only possessing) drugs. Several states, including Alabama, Missouri, and Texas, have recently modified the drug felon ban (almost 20 years after it went into effect) as part of broad criminal justice reforms.

It is important to note that the primary goal of sanctions is to provide a mechanism to help bring the household into compliance with what is being asked of them rather than as a means to punish households who fail to perform required tasks. Very little research has been undertaken in SNAP to assess the overall effectiveness of sanctions on incentivizing the desired results. Research in the TANF program suggests that a large proportion of families that are sanctioned for failing to comply with program activities are those with barriers to employment such as health and substance abuse problems or low levels of education. These findings suggest that work barriers can impede a recipient’s ability to meet program requirements and may be the cause of the failure to comply with requirements, rather than a willful refusal to comply. This may be because the particular work activities to which a recipient has been assigned are inappropriate, based on her individual circumstances, or that appropriate supportive services to help the recipient overcome her employment barriers are not in place. Placement in an inappropriate activity could arise because the states failed to identify the recipient as having a barrier, or a state may not have appropriate activities available for individuals whom it identifies as having particular barriers to employment.

Application Requirement Flexibility

In addition to flexibility regarding certain eligibility and benefit rules, SNAP affords states considerable flexibility, within federal standards, in the application and certification requirements they apply to households (for example, how often states require households to reapply for benefits, and which households they offer a telephone interview at application in lieu of a face-to-face interview.) This is an area of the program where the “flavor and feel” of the program can vary quite a bit across states.

This flexibility is bounded by program integrity standards and backed up by fiscal penalties on states for poor payment accuracy. SNAP’s Quality Control (QC) system has long been one of the most rigorous systems of any public benefit program in ensuring payment accuracy. Every month states select a representative sample of SNAP cases (totaling about 50,000 cases nationally over the year) and have independent state reviewers check the accuracy of the state’s eligibility and benefit decisions within federal guidelines. Federal officials then re-review a subsample of the cases to ensure accuracy in the error rates. States are subject to fiscal penalties if their error rates are persistently above the national average.

In many areas, because of this rigorous QC backstop, federal rules allow states flexibility in the procedures they apply to households. For example:

- Certification period length. States have options for how often they require households to reapply and have their eligibility reassessed. Federal rules require households be certified for fixed periods of time. States must require most households to reapply for SNAP at least annually, though states may allow households with more stable circumstances (i.e., households with elderly or disabled members who have fixed incomes) to reapply every two years. Within these federal rules states have flexibility for determining how often different types of households must reapply.

- Reporting changes. SNAP participants also are required to keep the state informed between eligibility reviews about certain changes in household circumstances (such as in income or household members). Federal rules present two basic reporting systems ¾ change reporting (changes must be reported within ten days), and periodic reporting (which requires reports periodically, usually every six months, though states may require reports monthly) ¾ and allow states to determine which households they assign to which type of system. SNAP households are frequently subject to other programs’ reporting requirements as well, most notably Medicaid but also child care and cash assistance through TANF or Supplemental Security Income (SSI).

- In-person or telephone interviews. SNAP rules require households to be interviewed at initial certification, and most households must be interviewed at least once a year thereafter. In recent years, in recognition of the burden that traveling to a local office can present to working families, seniors, and people with disabilities, and those with limited access to transportation, FNS has given states more flexibility in determining which households must visit an office for an in-person interview and for which households a telephone interview may be conducted.

- Verification. In SNAP certain items such as income, identity, and questionable information must be verified, either through a data match, household documents, or a contact with a reliable source. But states have a wide degree of latitude on what other items they require to be verified.

As mentioned, all of these choices operate within federal standards, and the rigorous QC system provides assurances that states make carefully considered choices that protect federal fiscal interests.

State Operations and Basic Business Model

Like with application and certification rules, states have a wide degree of flexibility for how they set up their SNAP program operations. Federal rules proscribe certain basic customer service standards; for example, most eligible households are expected to be provided benefits within 30 days of application (and, for the most destitute within seven days). And, of course, states cannot discriminate, cannot turn people seeking help away, and must comply with other laws that protect privacy and people with disabilities, for example.

But beyond these basic protections and standards, states have enormous flexibility to tailor their program operations — for example, how they staff their offices, coordinate with other programs, and deliver SNAP benefits. As a result, SNAP participants experience a wide range of different programs across the United States, and even within a given state, different counties and local offices may differ dramatically in their look and feel. Below are a series of examples of state flexibility in operations.

- Office structures. States have wide latitude over how they staff and structure their offices and develop and operate their own technology systems. So, for example, many, but all not all, states have online applications and other services such as the ability for applicants and participants to check their benefits online. Some states use call centers to centralize telephone operations, while others route inquiry calls to local eligibility offices.

- Staffing model. States can assign households to a particular eligibility worker or can operate on a “task model,” more like an assembly line, where staff share cases and different workers specialize in different certification activities, such as intake, interviewing, and case processing. Some might assign specially trained staff to address the particular needs of seniors or refugee groups. Some states make broad use of clerical staff, while others fully train almost all staff on the program’s eligibility rules.

- Coordination with other programs. States may offer SNAP as a stand-alone program, or may coordinate SNAP eligibility with other human services programs. Almost every state coordinates eligibility for SNAP with eligibility for TANF cash assistance (though employment and training may be separate), and about 40 states coordinate with health coverage through Medicaid. Some states also operate their energy assistance, child care, and/or refugee assistance programs in the same offices and using the same staff and eligibility systems as SNAP.

- Business process philosophy. Some states handle applications, mandated renewals or matches that require resolution as they come to the state. Other states seek to anticipate work and get ahead of it. For example if a client calls to report a change, a call-center worker might also check to see if the client is due for a renewal soon. If so, the worker could use that opportunity to conduct a quick interview with the client, run data matches and successfully complete the renewal. This proactive approach typically reduces workload for the state and provides better service to citizens.

- Speed of application processing. Even within the seven- and 30-day federal processing standards, states vary significantly on how quickly they determine eligibility. Some states, for example Idaho, focus on same-day services ¾ aiming to “touch” each case only once, and finalize the eligibility determination for as many cases as possible the same day. Other states take the full 30 days allowed under federal rules, waiting several weeks to schedule interviews and process verification. Both types of states are operating within federal standards.

- Benefit issuance. States also have flexibility in how they time benefit issuance. Each household receives its benefits monthly, but some states spread the date of issuance out over the first week of the month or the first 20 days, for example.

- Technology. One of the areas where states diverge the most from each other is the quality of their technology. Some states use a single modernized computer system across multiple programs. These systems offer them the ability to undertake speedy data matches (while on the phone with a client), review scanned client documents, chat with clients and accurately apply current eligibility rules. Work can be moved to where resources are available because it is all digitized. Clients have access to online accounts where they can transact business and may even have a mobile app on their phones where they can upload documents or quickly answer the states’ questions. Call centers answer the phone within minutes and have access to the necessary information to complete tasks with clients over the phone rather than forcing the client to take time off of work and travel to the local welfare office. Other states are working with decades-old systems, paper files, traditional phones (i.e., no headsets for workers on the phone) and have to wait for batch matching with third-party data systems such as the Social Security system to be undertaken by a central office. These differences are substantial and have a large impact on how the state conducts its business and how flexible and nimble it can be. For states with old computer systems, the reprogramming necessary to simplify program rules or align SNAP with other programs can be very difficult, if not impossible, or take years to implement.

Regulatory Waiver Authority

Under federal law, USDA can allow states to waive certain SNAP regulatory requirements in an effort to test innovative ways to improve program efficiency and to enhance client access. FNS has approved countless waivers using this authority. It keeps a public database of regulatory waivers; currently, there appear to be over 400 approved waivers.

For example, states have waivers to issue electronic notices to households that request them, in lieu of paper notices and to dispense with requirements on scheduling interviews if they commit to interview applicants “on demand” when they call a call center. Other examples are modest variations on benefit policy such as with respect to the calculation for how to average a student’s work hours. We would expect that early testing on electronic notices with a few states would result in guidance to all states on the use of such notices if they wish to use them. Similarly, the waivers on averaging student work hours might result in a revised policy that reflects states’ requests for more flexibility in that area.

Demonstration Waiver Authority

SNAP law has many state options built into its basic structure. In addition, in 1996, as part of the welfare law, Congress substantially expanded the program’s waiver authority to allow for greater state experimentation in SNAP. States can seek waivers to change virtually any aspect of the benefit structure and delivery system. The few limitations that Congress decided to retain after careful consideration are necessary to preserve the program’s fiscal integrity and to maintain SNAP as a nutritional safety net.

For example, to preserve fiscal integrity, the 1996 welfare law prohibited states from waiving the requirement that states contribute half of administrative costs. Without this restriction, states could seek waivers that entail cutting benefits and converting the savings into an enhanced administrative matching rate. Similarly, states cannot waive the prohibition against giving SNAP to residents of most institutions. Without this prohibition, states could use benefits to fund meals in state prisons or mental hospitals and offset the costs through SNAP benefit cuts.

To maintain the nutritional safety net, a handful of critical program rules cannot be waived. These include:

- The individual entitlement to benefits for eligible persons who are not violating work or other conduct requirements. Without this protection, states could make various categories of households ineligible for benefits or establish waiting lists in order to secure a source of funds for other purposes.

- The gross income limit for households that do not include elderly and disabled members. Without this prohibition, states could reduce benefits for poor and near-poor households to provide benefits for some groups of households at higher income levels, or could reduce the income limit for everyone to shift resources from SNAP benefits to other uses.

- Provision of timely service, such as the right to apply for SNAP when a household first contacts the SNAP office and to receive benefits within 30 days if eligible. Without these provisions, households in severe need could have to wait for long periods before receiving assistance.

Another important provision in current waiver authority appropriately distinguishes between demonstration projects that operate in several counties and are designed to test new approaches and waivers that simply allow a state to alter on a statewide basis a federal policy it does not favor. In the first type of waiver, which represents the type of approach followed over the years in a number of carefully evaluated pilot projects in various low-income programs, states are allowed broad discretion to alter the program’s benefit structure. (States may not make entire categories of low-income households ineligible for SNAP if these households are fully complying with all work and other behavioral requirements, but they can test changes that result in large changes in the benefits levels for which households qualify.) In the latter type of waiver involving statewide policy changes, states can still change many program rules, but there is a limit on the proportion of a state’s caseload whose benefits can be cut by more than 20 percent.[9]

This provision was included in the 1996 welfare law to ensure that waivers cannot simply eliminate or sharply reduce SNAP on a statewide basis for major categories of low-income households so long as the households are faithfully complying with program rules. Congress included it as an appropriate protection for a program that is designed to enable poor families and individuals to obtain a minimum adequate diet and in which the federal government pays 100 percent of the benefit costs.

Examples of demonstration waivers under this authority include demonstrations to test:

- the impact of simplifying the process by which eligible households can claim the medical expense deduction, and

- a simplified application process for seniors who qualify for SSI to be enrolled into SNAP.

While not required under federal law, USDA has consistently required that these demonstration projects be cost neutral to the federal government to ensure that this authority is not abused to expand or contract the program.

SNAP Employment and Training Programs

SNAP employment and training (E&T) is one of the most flexible program features of SNAP. This ensures that states can design programs that are suited to their local economic conditions in terms of which populations they target with services, what services to offer, and in which localities. The primary limitation states experience under employment and training is limited federal grant funds. States are, however, eligible for unlimited federal matching funds to double state investments in operate SNAP employment and training programs. Under SNAP rules, all adult recipients are required to register for work unless they are elderly, disabled, caring for a child under age six, already complying with a TANF or unemployment compensation work requirement, or otherwise not expected to work. States have very broad discretion to require work registrants to look for jobs, to participate in employment and training activities, or to work off their benefits.

In 1996, Congress restructured the SNAP E&T program to serve primarily unemployed childless adults. As mentioned above, under the welfare law, such individuals may receive SNAP benefits for only three months out of any three-year period unless they are participating in a work program. States criticized the provisions directing most federal SNAP E&T money to unemployed childless adults as overly restrictive, and the reauthorization legislation enacted in May 2002 as part of the Farm Bill returned the E&T program to its prior, more flexible design. States once again have almost complete flexibility over how they operate their E&T programs. They may determine which populations to serve (for example, parents in families with children or unemployed childless adults) and select what types of employment and training services to provide. They may access federal matching funds for these employment and training services and related work support services, including transportation and child care.

As part of the 2013 Farm Bill, Congress authorized ten pilot projects to test whether SNAP E&T could more effectively connect unemployed and underemployed recipients to work. The selected pilots, announced in March 2015, include a mix of mandatory and voluntary E&T programs. Several of the pilots target individuals who face significant barriers to employment, including homeless adults, the long-term unemployed, individuals in the correctional system, and individuals with substance addiction. Each pilot involves multiple partners to connect workers to resources and services already available in the community. These pilots will help both states and the federal government understand how SNAP E&T can best contribute to recipients ultimately securing jobs that provide economic security and end their need for SNAP.

Other Flexibilities

As I noted above, this section is meant to give a sense of the categories of flexibility in the program rather than a comprehensive catalogue of all the state options and choices within SNAP. Within each category there are other examples, many of them less significant or less popular than the listed items. And, other program features provide flexibility as well. SNAP provides a nutrition education grant to states under which states can pursue nutrition education programming of their choice so long as it is evidence based. States also have flexibility in establishing and operating outreach services to help connect eligible but unenrolled individuals and families with SNAP. And, if a state experiences a natural disaster, states have the option to establish special disaster-SNAP (D-SNAP) that is customized to the needs in the impacted community within certain parameters.

States Are Not Always Aware of SNAP’s Flexibility

I have worked on SNAP for more than 20 years. Much of my work is providing technical assistance to state officials who wish to explore options to improve their program operations. It has been my great pleasure to visit local offices and work with states all around the country. Most recently, I led technical assistance to states as a part of the Work Support Strategies Initiative (WSS) — a multi-year, multi-state initiative to help low-income working families obtain the package of work supports for which they are eligible, while enabling states to streamline administration. WSS worked directly with Colorado, Idaho, Illinois, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and South Carolina since 2011. Through grants and expert technical assistance, WSS helps states reform and align their systems for delivering work-support programs intended to increase families’ well-being and stability — particularly SNAP, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and child care assistance through the Child Care and Development Block Grant. Through WSS, states seek to streamline and integrate service delivery, use 21st Century technology, and apply innovative business practices to improve administrative efficiency and reduce burdens on both states and working families.

Based on my experience, many states are not fully aware of the level of flexibility available to them. They often assume that their states’ SNAP program rules are mandated by the federal government. Instead, their program is a mixture of federal rules and a set of choices by their predecessors in the state that was informed by circumstances or limitations that may no longer be relevant. This is particularly true of state computer systems — when states purchase systems that are inflexible, they often call on the federal agencies to provide flexibility to let them align the programs with their technology.

It also can be difficult for state officials to assess which rules were mandated and which are the result of prior state choices – now codified in state manuals and computer programming. This doesn’t mean there aren’t federal requirements in SNAP and other health and human services programs — there certainly are. But, often states perceive SNAP as far more rigid than it is. One of the biggest areas that states struggle with is how to coordinate policies and procedures across programs. Perfect alignment isn’t possible, but there’s far more opportunity for coordination than many realize. We saw this recently when we interviewed states and conducted site visits on how states coordinate SNAP and Medicaid renewals. In many cases, the limitations of their computer systems were driving policy decisions, rather than policy choices driving the state’s computer system design.

As states work to better coordinate their systems, they are discovering that there is often far more flexibility in federal programs to align and coordinate, or cross-leverage, information than they thought. Often disconnects are the result of their own making or a lack of understanding of the flexibility available to them. Other times, differences between programs are by design and originate from the programs’ differing goals. And, there are times when states discover differences between programs that raise reasonable questions. For example, several states have asked if they can use the wage and unemployment data that employers report to states and Social Security Administration to help verify household income as the basis for eligibility and benefit-level determination. Traditionally, this would not be allowed in SNAP because the data would be consider too old (up to four or five months) to use as a current assessment of household circumstances. Nevertheless, USDA is allowing a few states to test this approach in an effort to determine if this approach is workable, particularly for households with very stable income. Another example is that Medicaid allows and encourages states to use third-party data matches to verify income even if the information is a little dated, while SNAP historically has required states to gather current information, even from households with very stable employment arrangements. In such a case, the federal government can grant states waivers from federal SNAP requirements to test whether allowing SNAP to use other programs’ rules is appropriate and cost effective. I believe Texas is currently testing this approach, which may help USDA determine whether and under what conditions this approach may be workable in SNAP.

USDA can do more to assist states’ efforts to administer SNAP as part of the larger health and human services system. First and foremost, USDA’s oversight and policy development would be strengthened if its staff developed more expertise in other federal assistance programs. When SNAP policy is different from policy in another major program such as Medicaid, it would be helpful for USDA to be aware of those differences, to flag them for states, and to be able to advise states on the flexibility they may have to harmonize the rules across programs. (The same holds true for HHS.) State and local governments, even individual caseworkers, ought not to be left on their own to disentangle differing federal rules and regulations. It seems reasonable for the federal agencies to navigate what we ask their state counterparts to manage. That having been said, USDA has taken steps to engage SNAP agencies in a conversation about how recent changes in Medicaid could be affecting SNAP operations at the local level. USDA can do more here, and I encourage them to do so.

Conclusion

SNAP is an efficient and effective program. It alleviates hunger and poverty and has positive impacts on the long-term outcomes of those who receive its benefits. And, SNAP has exacting standards with respect to eligibility determinations.

Congress and USDA have worked hard to balance the need to maintain SNAP’s successful structure and design with some state flexibility to ensure the program is able to adapt to local circumstances, respond to the needs of underserved groups such as working families and seniors, and test new ideas to improve the program’s efficiency without compromising its effectiveness. In general, these options are meant to augment SNAP, rather than weaken or compromise its ability to meet the basic nutrition needs of struggling Americans. As you consider state flexibility and state options in the program, I urge you to keep that goal as your priority.

Thank you.

End Notes

[1] Congressional Budget Office, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” April 2012, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/04-19-SNAP.pdf.

[2] Hilary W. Hoynes, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Douglas Almond, “Long Run Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 18535, 2012, www.nber.org/papers/w18535.

[3] See the fiscal year 2014 error rates: http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/quality-control.

[4] For both SNAP and taxes the figures represent gross estimates (i.e., before SNAP households repay overpayments, taxpayers make voluntary late payments, or consideration of IRS enforcement activities.) The net costs are somewhat lower. See: Internal Revenue Service, “Tax Gap for Tax Year 2006, Overview,” January 6, 2012, http://www.irs.gov/pub/newsroom/overview_tax_gap_2006.pdf.

[5] CBPP analysis of the Census Bureau’s March 2015 Current Population Survey. See Jennifer Wagner and Alicia Huguelet, “Opportunities for States to Coordinate Medicaid and SNAP Renewals,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 5, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/opportunities-for-states-to-coordinate-medicaid-and-snap-renewals.

[6] Peter Ganong and Jeffrey B. Liebman, “The Decline, Rebound, and Further Rise in SNAP Enrollment: Disentangling Business Cycle Fluctuations and Policy Changes,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 19363, August 2013, http://www.nber.org/papers/w19363.pdf?new_window=1. See Dottie Rosenbaum and Brynne Keith-Jennings, “SNAP Costs and Caseloads Declining,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated February 10, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-costs-and-caseloads-declining.

[7] “Imposing a Time Limit on Food Stamp Receipt: Implementation of the Provision and Effects on Participation,” Mathematica Policy Research, 2001, available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/abawd.pdf.

[8] Ed Bolen, et al., “More Than 500,000 Adults Will Lose SNAP Benefits in 2016 as Waivers Expire,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated January 21, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/more-than-500000-adults-will-lose-snap-benefits-in-2016-as-waivers-expire.

[9] Dorothy Rosenbaum, “States Have Significant Flexibility in the Food Stamp Program,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 17, 2002, https://www.cbpp.org/archives/6-17-02fs.htm.

More from the Authors