The House Appropriations Committee this week approved a fiscal year 2015 funding bill covering the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) that makes disproportionately deep cuts in housing assistance for low-income families. Congress is operating under tight spending limits set by the Budget Control Act (BCA) and the two-year Murray-Ryan budget deal, and a projected decline in incoming revenues from mortgage credit programs has made the funding limits for non-defense discretionary programs still more austere. But the funding allocations that the House Appropriations Committee provided to its 12 subcommittees aggravated this problem by targeting the two appropriations bills with the greatest concentration of discretionary programs serving low-income people for the largest dollar cuts, including the Transportation-HUD appropriations bill. And, the Committee has now produced a “T-HUD” funding bill for fiscal year 2015 in which the funding cuts for HUD’s low-income housing assistance programs are twice as deep, in percentage terms, as the overall percentage funding reduction for non-defense discretionary programs that’s required to comply with the BCA caps.[1]

The House bill provides $35 billion for HUD, an amount that appears at first blush to be a $2.1 billion increase over 2014. However, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that receipts from Federal Housing Administration (FHA) insurance and Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA, or Ginnie Mae) mortgage guarantee programs — which are credited to the HUD budget against program funding levels — will decline by nearly $3 billion from 2014 to 2015, which results in the bill’s significantly reducing the overall level of funding for HUD programs and operations. In an apples-to-apples comparison of funding (not counting these receipts, which CBO estimates will total $9.7 billion in 2015), the House bill provides $44.7 billion in new funding for HUD programs in 2015 — or $740 million less than the $45.5 billion Congress allocated for 2014.[2] And the bill takes the majority of this $740 million out of programs for low-income families and individuals.

The House bill’s disproportionate reductions in these programs will mean less rental assistance, and greater hardships, for low-income families. Specifically, the House bill would:

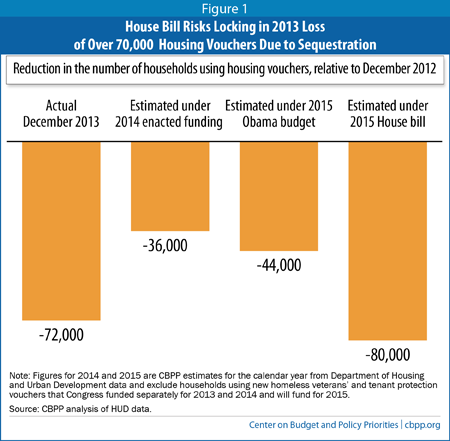

- Risk locking in the loss of more than 70,000 Housing Choice Vouchers cut in 2013 due to sequestration. In 2014, Congress provided enough funding to restore about half of the more than 70,000 vouchers cut in 2013 as a result of sequestration and to renew close to 2.15 million housing vouchers overall. But the new House bill fails to renew all of these vouchers in 2015. The bill also cuts funding for the administrative expenses that local housing agencies incur in operating housing voucher programs by $150 million while failing to include any of a widely supported set of changes to streamline program administration, increase efficiency, and help agencies cut costs, such as by allowing them to reduce the frequency of income checks for residents on fixed incomes such as poor elderly individuals living on modest Social Security checks.

- Stall recent progress on reducing homelessness. The bill would freeze funding for homeless assistance grants at the 2014 level, rejecting the President’s 2015 budget request for a $301 million increase to develop 37,000 new units of permanent supportive housing for people with disabilities who have been homeless for extended periods. The numbers of so-called “chronically” homeless people have fallen by 16 percent since 2010, according to HUD, and the additional units of supportive housing are needed to achieve the worthy goal of eliminating chronic homelessness by 2016. While the House bill does contain $75 million for approximately 10,000 new housing vouchers for homeless veterans, the bill does not provide sufficient funds to renew all of the housing vouchers that Congress funded in 2014, as just noted, which include more than 60,000 vouchers targeted to homeless veterans that Congress has funded in prior years. The failure to renew all housing vouchers now in use means that fewer low-income families and individuals would receive any rental assistance, which likely would result in some increase in homelessness.

- Deepen the underfunding of public housing. The House bill would cut funding for public housing by $165 million below the 2014 level, even before adjusting for inflation, despite the fact that the 2014 level itself was well below what HUD metrics show public housing agencies need to operate public housing developments and meet pressing repair needs. The cuts would increase the risk that living conditions for a number of the 1 million households living in public housing, most of which consist of seniors or people with disabilities, will deteriorate. The House bill also omits an important Administration proposal to expand the Rental Assistance Demonstration, a promising initiative that enables agencies to respond to the shortage of funding for repairs by leveraging private investment to renovate public housing.

- Reduce funding for new affordable housing and impose deep cuts in other areas across the HUD budget. The bill would cut funding for the HOME Private Investment Partnerships program, which helps states and localities rehabilitate or build new affordable rental housing and assist low-income homeowners, by $300 million — or 30 percent — below the 2014 level. The bill also contains: a $40 million, or 36 percent, cut in lead-based paint hazard reduction grants; a $27 million (8 percent) reduction in Housing Opportunities for People with AIDS (HOPWA) grants; and a $20 million (30 percent) cut in grants in support of fair housing enforcement activities.

The growth in the number of low-income renters struggling to afford decent, safe housing has been unprecedented over the past decade, and despite recent progress in some areas, homelessness remains a persistent and devastating problem. Reductions in programs that help low-income seniors, people with disabilities, families with children, and others to avoid homelessness and other hardships exacerbated by unaffordable housing costs reflect misplaced budget priorities. To avoid making these problems worse in 2015, Congress should provide sufficient funding to sustain existing rental assistance. It should also continue to roll back the effect of recent sequestration cuts on basic rental assistance for poor families and make progress in reducing homelessness.

The Housing Choice Voucher program (also known as “tenant-based rental assistance”) is the largest of the rental assistance programs that together form an important part of the federal safety net. Half of the 2.1 million low-income households using rental vouchers are seniors or people with disabilities; most of the rest are families with children. The vast majority of these households are poor — their average annual incomes are about $13,000 — and they face a heightened risk of homelessness without rental assistance.[3]

The across-the-board sequestration cuts in 2013 forced housing agencies to reduce the number of families receiving voucher assistance by more than 70,000 from December 2012 to December 2013, and these reductions have likely deepened in the early months of 2014.[4] After more than a decade of sharp and unprecedented growth in the number of low-income households that have difficulty finding affordable housing,[5] this loss of rental assistance has had harsh effects. Following the two-year Murray-Ryan budget agreement, which moderated sequestration for 2014 and 2015, Congress raised funding for housing vouchers for 2014 above the depressed 2013 post-sequestration level. This increase will enable housing agencies to restore up to half of the vouchers lost the previous year due to sequestration.

The House Transportation-HUD (THUD) funding bill for fiscal year 2015, however, threatens to reverse these efforts to restore housing vouchers and to lock in the loss of the more than 70,000 vouchers that were cut in 2013. (See Figure 1.) The bill, which the House Appropriations Committee approved on May 21, would provide $19.4 billion for Housing Choice Vouchers in 2015, including $17.7 billion to renew housing vouchers in use in 2014. The latter is an increase of $328 million above 2014 renewal funding, but $313 million less than the amount that the President requested in his 2015 budget.

Of the $328 million the House bill would add for renewals in 2015, however, approximately $300 million is needed just to renew 10,000 homeless veterans’ (VASH) vouchers that were provided for the first time in 2013 or 2014 and nearly 30,000 tenant-protection vouchers for which Congress provided initial funding in 2014. These sets of vouchers were funded through different funding streams in 2013 and 2014, but need to be renewed in 2015 with

voucher renewal funding.

[6] HUD awards tenant-protection vouchers to

replace aid for families living in public or private assisted housing that is being demolished or otherwise removed from the housing available through

other federal rental assistance programs. These vouchers thus do

not constitute a net increase in federal rental assistance or in the number of low-income households served.

The House bill thus provides an increase of only $28 million, or less than 0.2 percent, to cover rent and utility cost inflation for the housing vouchers that the other 2.1 million families the program serves are expected to use in 2014. Yet families using vouchers in the private market face rent and utility costs that have grown by 2.7 percent over the past year, according to both HUD’s Fair Market Rent estimates and the latest Consumer Price Index (CPI) data.[7] If these cost trends continue into 2015, the HCV program will confront a renewal funding shortfall of $369 million under the House bill.[8]

To contend with a shortfall of this magnitude, housing agencies have two basic choices, both of which would worsen hardships for low-income families. First, they can assist fewer families — for instance, by not reissuing housing vouchers to families on their waiting lists when current voucher-holders leave the program. Figure 1 above shows the projected outcome if housing agencies were to reduce the number of families they assist in 2015 to make up for a $369 million shortfall: the number of families receiving assistance would fall back below the level following the sequestration cuts in 2013. In effect, this would lock in the loss of housing vouchers for more than 70,000 low-income families.[9]

Second, agencies can shift the full burden of increased rent and utility costs onto low-income families by freezing (or even reducing) the amount of subsidy for some or all of the vouchers they administer. This forces families either to devote more of their meager household budgets to housing costs to remain in their homes — and to cut back on spending on food, medicines, or other essentials — or to move to a lower-cost home, if one is available. If families choose the latter option, they may be forced to move to neighborhoods that are less safe or have fewer opportunities such as ready access to jobs or good schools. Subsidies that do not keep pace with rising costs in the private housing market also make it more difficult for newly assisted families to use vouchers at all, as federal regulations prohibit a new family from leasing housing at a cost that exceeds 40 percent of their income.[10]

In a May 6 press release, the House THUD Subcommittee asserted that the HCV funding in the bill “will provide for continued assistance to all families and individuals currently served by this program.”[11] As the discussion above makes clear, however, this can be true only if one of two unfortunate developments occurs: first, if housing agencies do not use the funds available in 2014 to restore any of the 70,000 housing vouchers that were cut in 2013 due to sequestration; or second, if housing agencies freeze voucher subsidies in spite of rising rent and utility costs. In short, the House bill will be sufficient to serve the same number of low-income people only if the program serves tens of thousands of fewer families this year than funding will permit or if low-income families absorb significant increases in housing costs over the next year, effectively pushing them deeper into poverty with respect to other household needs.

The House bill also cuts funding for HCV program administration by $150 million, or 10 percent, relative to the 2014 level (returning funding to roughly the post-sequestration level in 2013, adjusted for inflation). Housing agencies would receive only 66 percent of the funds for which they are eligible under HUD’s cost formula.[12]

Such shortfalls make it difficult for agencies to perform basic but essential tasks such as inspecting housing units to ensure they meet federal housing quality standards for condition and safety. Moreover, the House bill fails to include any policy changes to streamline program administration and reduce agency costs. One worthwhile change would be to allow agencies to re-examine and recertify the incomes of elderly and disabled people living on fixed incomes every two or three years instead of every year. This change is broadly supported by stakeholders.

Federal support has helped some local communities reduce homelessness significantly in recent years. Recent data collected by HUD indicate, for example, that long-term homelessness among people with serious disabilities has fallen by 16 percent since 2010, and homelessness among veterans has declined by nearly one-quarter. It is also widely believed that the $1.5 billion that Congress provided to communities through the 2009 Recovery Act to provide short-term rental and other types of financial assistance to prevent homelessness and to help homeless people move into more permanent housing successfully mitigated the housing hardships that low-income households experienced during the Great Recession.

The House THUD bill threatens to stall this progress. First, locking in the sequestration cuts in Housing Choice Vouchers will undercut many communities’ efforts to reduce homelessness. Overall, one in five housing agencies target housing vouchers to individuals and families who are homeless, and some have committed significant numbers of vouchers to local strategic plans to reduce homelessness. These commitments can be met, however, only if sufficient housing vouchers are available, and agencies were forced to retrench on their commitments in 2013 due to sequestration. The House bill would force some agencies to retrench once again in 2015.

Second, the House bill freezes funding for homeless assistance grants at $2.1 billion in 2015, some $301 million less than the President’s budget requests. This includes $15 million less than the President’s request for Emergency Solutions Grants, which fund homelessness prevention and rapid rehousing activities (the same types of activities that proved successful during the Great Recession) as well as the operation of temporary shelters. The House bill also reduces the President’s request for Continuum of Care grants, which communities use largely to provide a package of rental assistance and supportive services to homeless individuals and families, by $284 million; the President’s budget had earmarked these funds for the development of an additional 37,000 units of permanent supportive housing to help meet the goal of the federal strategic plan on homelessness to end chronic homelessness by 2016.

The House bill does include $75 million for approximately 10,000 new housing vouchers for homeless veterans under the Veterans’ Administration-HUD Supportive Housing (VASH) program, which continues efforts to reduce homelessness among veterans. But, as explained above, the House bill would successfully renew the more than 60,000 VASH vouchers that Congress has funded since 2008 only if state and local housing agencies reduce the number of families assisted in the remainder of their voucher programs or shift the burden of rent and utility increases in the private rental-housing market onto the low-income seniors, people with disabilities, families with children, and others who use rental housing vouchers. In short, any progress made in reducing veterans’ homelessness would be offset, at least in part, by reducing assistance for other families — and possibly increasing homelessness among them.

The House bill would also strike a blow to public housing, which provides affordable housing to 1 million low-income households. More than half of these households are seniors or people with disabilities; most of the rest are families with children.[13]

The federal government provides subsidies to fill the gap between the rents that low-income families living in public housing can afford (by paying 30 percent of their incomes) and the cost of operating and maintaining public housing developments. These subsidies are provided largely through two streams: the Operating Fund (to cover the costs of handling admissions, maintenance, security, utilities, and the like that aren’t met by tenant rent payments) and the Capital Fund (for major repairs and renovations).

While most public housing developments still manage to meet federal housing quality standards, chronic underfunding has created a large backlog of repair, renovation, and other capital investment needs. A 2010 HUD-sponsored report found that public housing developments had accumulated a $26 billion backlog of capital needs.[14]

The House bill would continue and deepen the shortfalls in public housing funding, which over time will cause living conditions for more low-income families to deteriorate — and the loss of affordable units (due to lack of needed repairs and maintenance) to accelerate. The bill provides $1.78 billion for capital repairs, $100 million below the 2014 level and only half the amount agencies need to cover the new repair and renovation needs likely to develop this year according to the HUD report cited above. The bill also includes just $25 million for the Choice Neighborhoods Initiative, which largely funds public housing redevelopment in concert with a broader investment strategy aimed at revitalizing distressed communities; this is $65 million below the 2014 level. For public housing operations, the bill provides $4.4 billion, which would cover only about 86 percent of the funds that agencies will need to operate their developments adequately in 2015, according to HUD’s budget estimate.

When federal funding is inadequate, some agencies can make ends meet by drawing on reserves or reducing unnecessary administrative costs. Following many years of underfunding, however, the remaining opportunities for such relatively painless measures have dwindled.

Instead, many agencies will be forced to raise revenue or reduce expenses through steps that can have harmful consequences for low-income families. While agencies cannot institute across-the-board increases in rents, which generally equal 30 percent of household income, agencies can generate added revenues by passing more utility costs on to tenants, raising fees for parking and other services, or exercising their discretion to set minimum rents of up to $50 a month on the very-lowest-income families. In addition, when tenants move out, agencies can opt to rent their units to families with somewhat higher incomes since those families can afford higher rents, even though they have less need for housing assistance (and are at much lower risk of homelessness) than poorer families.

Agencies will also likely cope with shortfalls by cutting back spending in areas such as security and maintenance. Major maintenance cutbacks, however, could cause living conditions to deteriorate and leave serious safety hazards undressed, such as broken fire sprinklers or defective elevators in high-rise developments. In addition, if agencies cut back on maintenance of building grounds and exteriors, this could lead to blight that would harm surrounding communities. Deferring some types of repairs, such as patching leaky roofs, could result in higher costs down the road.

Ultimately, if Congress fails to provide adequate resources for operations and renovation year after year, many public housing developments will deteriorate to the point that they are no longer habitable and will be lost as affordable housing. Already, more than 260,000 public housing units have been demolished or otherwise removed from the stock since the mid-1990s.

When the funding that Congress provides consistently falls short of the amount that housing agencies need to preserve public housing developments for the long run, it becomes imperative for policymakers to ease agencies’ access to private loans and other investments to supplement federal funds. The President’s budget proposed to take a modest but important step in this direction by eliminating a cap on the number of public housing units that can be included in the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD). RAD allows agencies to convert public housing to long-term project-based Section 8 contracts that provide reliable funding and make it easier to leverage private-sector investment to preserve developments. Housing agencies have applied to convert more than 175,000 units under RAD, but conversions are currently capped by law at 60,000 units. The House bill does not include authority to raise the cap on RAD conversions, even though doing so would not increase federal costs.

The House bill provides $9.7 billion for Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA) for fiscal year 2015. This is a $171 million reduction from 2014 funding but is consistent with a plan the President’s budget proposes to transition the program over two years to a calendar-year funding cycle that should be more transparent and stable.

Congress has long sustained a strong commitment to fully renewing HUD’s Section 8 PBRA contracts with private owners — and rightfully so, as about 1.2 million low-income households, two-thirds of which are seniors or people with disabilities, rely on this rental assistance to afford housing. Over the past eight years, however, the program has experienced fluctuations in funding (including sequestration in 2013) and funding policy changes that have generated uncertainty and concern among owners and their lenders and investors about the future reliability of funding for Section 8 PBRA contracts. These concerns have been heightened by the recognition that Congress faces severe fiscal constraints under the Budget Control Act spending caps.

Within this context, the President’s budget proposes to transition Section 8 PBRA in fiscal years 2015 and 2016 to a funding cycle in which each year’s appropriation would cover rental assistance contract payments due for January through December (that is, extending three months into the following fiscal year, which begins on October 1). This proposal modestly reduces the amount of new funding required for 2015, as the fiscal year 2014 appropriation will be sufficient to make payments on some Section 8 PBRA contracts through the early months of calendar year 2015, leaving a reduced amount for the fiscal year 2015 appropriation to cover. In fiscal year 2016, however, sufficient funding to cover a full 12 months’ of rental assistance payments — which HUD currently estimates will cost about $10.9 billion, or $1.2 billion more than the President’s 2015 funding request — will be needed. As part of the proposal, the Administration is committing to including this funding in its fiscal year 2016 budget request.

The proposed policy would be a change from Congress’ traditional policy of providing, in advance, sufficient budget authority to cover contract payments for many months beyond the end of the current federal fiscal year. Yet there is no strong argument, other than custom, in favor of forward funding Section 8 PBRA contracts in that way. What matters most to owners is that HUD deliver monthly payments to owners on time, in accordance with the terms of their contracts. The budgeting process that underlies these payments is largely invisible to owners, as it should be.

Stakeholders have raised concerns that the Administration’s proposal will deepen lenders’ and investors’ worries about the future reliability of Section 8 PBRA contracts. Similar concerns were raised in the wake of sequestration in 2013, which forced HUD to “short fund” contracts — that is, to obligate less than 12 months of funding for roughly half of Section 8 PBRA contracts in fiscal year 2013 and an additional number in fiscal year 2014. However, any negative reaction is likely to be temporary, so long as HUD continues to make timely contract payments (as it has succeeded in doing following sequestration).

Indeed, a calendar year funding policy could help to alleviate some lender and investor concerns. HUD’s implementation of the current policy of “short funding” contracts is entirely ad hoc and opaque to owners. Under a firm calendar-year funding policy, it would be clear to owners that each year’s appropriation would cover 12 months’ of payments for all contracts.

Congress is facing serious fiscal constraints in writing the fiscal year 2015 appropriations bills, and the unexpected decline in CBO’s projection of FHA and GNMA receipts has tightened these constraints markedly. But Congress should set priorities to provide the resources needed to sustain the rental assistance on which millions of low-income families rely to avoid homelessness and other hardships. The House THUD spending bill fails to do this, imposing disproportionately deep cuts in rental assistance for low-income households.

The Senate should aim to do better. To protect low-income families, Congress should at least meet the President’s request for funding for Housing Choice Vouchers, public housing, and homeless assistance grants, and should seek additional funds to restore to use the remainder of the 70,000 housing vouchers that were cut last year due to sequestration.