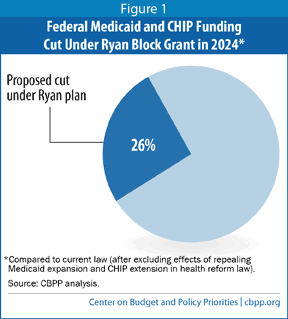

The Medicaid block grant proposal in the budget plan proposed by House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan on April 1 would cut federal Medicaid (and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, or CHIP) funding by 26 percent by 2024, because the funding would no longer keep pace with health care costs or with expected Medicaid enrollment growth as the population ages. (See Figure 1.) These cuts would come on top of repealing the health reform law’s Medicaid expansion.

Cuts of this magnitude would substantially — and adversely — affect millions of low-income Americans’ ability to secure health coverage and access needed health-care services. Medicaid cannot readily withstand cuts of this depth without harmful results for low-income families and individuals. The program already costs significantly less per beneficiary than private insurance does, because it pays health providers much lower rates and has considerably lower administrative costs. In addition, its per-beneficiary costs have been rising more slowly than private insurance premiums for the past decade, and they are expected to grow no faster than private insurance over the next ten years.

Chairman Ryan claims in his budget plan that the block grant would ease states’ fiscal burdens, improve the safety net for low-income Americans, and provide better access to care among beneficiaries. In its analysis of the similar block grant from the House’s budget plan in 2012, however, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) concluded that unless states increased their own Medicaid funding very substantially to make up for the Ryan plan’s deep Medicaid funding cuts, they would have to take such steps as cutting eligibility, which would lead to more uninsured low-income people; cutting covered health services, which would lead to more underinsured low-income people; and/or cutting the already low payment rates to health care providers, which would likely cause more doctors, hospitals, and nursing homes to withdraw from Medicaid and thereby reduce beneficiaries’ access to care.

The Urban Institute similarly estimated that the 2012 block grant proposal would lead states to drop between 14.3 million and 20.5 million people from Medicaid by the tenth year. (That would be in addition to the 13 million people who would lose their new coverage or no longer gain coverage in the future due to repeal of the Medicaid expansion, with the number rising as high as 17 million if all states take up the expansion.) More than 40 million people would likely end up losing coverage overall after also taking into account the budget’s repeal of health reform’s exchange subsidies. The Urban Institute also estimated that the 2012 block grant proposal would have resulted in cuts in reimbursements to health care providers and managed care plans of more than 30 percent by the tenth year. This year’s proposal in Ryan’s budget would likely result in similarly severe cuts.

Under the Ryan budget’s proposal to replace Medicaid with a block grant, the federal government would no longer pay a fixed share of states’ Medicaid costs.[1] States would instead receive a fixed dollar amount that would rise annually with inflation and population growth.[2]

Like last year’s block grant proposal, however, the fiscal year 2015 Ryan plan provides little detail about its Medicaid block grant proposal.[3] Starting in fiscal year 2016, states would receive a fixed dollar amount of Medicaid funding. Federal funding that would otherwise be available to states under CHIP would be merged into the block grant as well.[4] The combined block grant amounts for subsequent years would be based on the prior year’s amount, adjusted presumably for general inflation and U.S. population growth.

Because the block grant funding levels would not keep pace with health care costs or the expected increase in the number of Medicaid beneficiaries — especially the growth in the number of elderly beneficiaries, who cost more to serve — the block-grant funding levels would fall further behind need with each passing year. The percentage increase in the block-grant funding level from one year to the next would average about 3.5 percentage points less per year than what CBO expects to be the Medicaid program’s average growth rate over the coming decade under current law (outside of health reform’s Medicaid expansion).

According to the Ryan budget plan, the block grant proposal would shrink federal Medicaid and CHIP funding by $732 billion — or 19.3 percent — over the next ten years, relative to current law.[5] This does not count the loss of the additional federal Medicaid funding that states would receive under health reform’s Medicaid expansion and the extension of funding for the CHIP program (for 2014 and 2015), both of which the Ryan budget would repeal. (Reductions to CHIP funding, compared to baseline funding levels, would likely constitute only a very small share of the $732 billion in cuts due to CHIP’s very small size relative to the Medicaid program.)

By 2024, federal Medicaid and CHIP funding would be cut $124 billion for that year alone, an estimated reduction of 26 percent compared to what states otherwise would receive for that year under current law (see Table 1 for the year-by-year funding reductions).[6] The percentage cut would continue to grow larger each year after that.

Table 1

Federal Medicaid and CHIP Spending Cuts Required by Ryan Block Grant

In billions of dollars |

| | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2015-2024 |

Federal Medicaid

and CHIP Baseline

Spending * | 302 | 313 | 329 | 343 | 363 | 384 | 406 | 429 | 451 | 477 | 3,797 |

Medicaid Spending

Cuts Under Ryan

Block Grant ** | n/a | -31 | -47 | -62 | -71 | -80 | -93 | -106 | -118 | -124 | -732 |

| Percentage Cut | n/a | -10% | -14% | -18% | -20% | -21% | -23% | -25% | -26% | -26% | -19% |

*Excludes spending related to the Medicaid expansion and the extension of CHIP for 2015 under the Affordable Care Act, which would both be repealed.

**As specified under Table S-4 of the Ryan budget plan summary.

Source: CBPP analysis using Congressional Budget Office baseline estimates and House Budget Committee, “The Path to Prosperity: Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Resolution,” April 1, 2014. Figures may not sum due to rounding. |

Moreover, these funding cuts would be even larger in years when enrollment or per-beneficiary health care costs rise faster than is currently projected. Unlike under the current Medicaid program, where federal funding rises automatically in response to a recession or unanticipated costs from epidemics or medical breakthroughs, states would have to bear all such added costs themselves.

Under the block grant, states would be given expansive new flexibility in their Medicaid programs in areas such as eligibility and benefits. In his budget plan, Chairman Ryan claims that states would be able to use flexibility to tailor their Medicaid programs and “improve the health-care safety net for low-income Americans by giving states the ability to offer their Medicaid populations more options and better access to care.” He implies that states could make up for federal funding reductions by instituting innovative reforms that produce cost savings while improving quality of care and beneficiary satisfaction.[7]

However, as CBO concluded when it analyzed the similar Medicaid block grant included in the House budget plan from 2012, while states may be able to use this new flexibility to improve the efficiency of their programs:

[T]he magnitude of the reduction in spending . . . means that states would need to increase their spending on these programs, make considerable cutbacks in them, or both. Cutbacks might involve reduced eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP, coverage of fewer services, lower payments to providers, or increased cost-sharing by beneficiaries — all of which would reduce access to care.[8]

In other words, unless states come up with substantial new sums to offset the very large losses in federal funding, they would be compelled to institute deep cuts to their Medicaid programs.

States almost certainly would reduce eligibility, coverage, or both, for beneficiaries as well as payments to health care providers and managed care plans. These reductions would be deepest in periods such as recessions when states face significant revenue declines and have the hardest time contributing any additional state funding but the number of people in need of Medicaid increases. Cuts could include some or all of the following types of measures:

- States could cap Medicaid enrollment and turn eligible families and individuals away — in contrast to current law, under which all eligible individuals who apply must be allowed to enroll. The Urban Institute estimated that the similar Medicaid block grant in the House budget plan in 2012 would cause states to shrink the number of low-income people receiving health coverage through Medicaid by between 14.3 million and 20.5 million people by 2022 (not including the number of individuals who would lose Medicaid coverage because of the repeal of the Medicaid expansion) — which would constitute an enrollment reduction of 25 percent to 35 percent.[9]

- Medicaid covers certain services typically not available through private insurance that are tailored to meet the needs of especially vulnerable beneficiaries — particularly low-income people with severe disabilities — who traditionally have been excluded from the private insurance market. Such services, including case management and therapy services, are important for poor people with serious disabilities but can be costly. Faced with very large federal funding cuts, states likely would curtail a number of these services.

- The reductions in federal funding would likely cause many states to scale back coverage for low-income seniors and people with disabilities, especially for long-term care. Low-income seniors and people with disabilities make up one-quarter of Medicaid beneficiaries but account for about two-thirds of all Medicaid expenditures (because of their greater health care needs and because Medicaid is the nation’s primary funder of long-term care). This could mean that fewer seniors and people with disabilities with long-term care needs would receive coverage for services and supports they need to stay in their homes.[10]

- States also could charge low-income beneficiaries substantial premiums, deductibles, and co-payments. Medicaid currently ensures that coverage is affordable for low-income people by generally not charging premiums and keeping cost-sharing charges modest; research has found that premiums and cost-sharing lead many low-income households to remain uninsured or to forgo needed care. Under a block grant, however, states could begin charging substantial premiums, which could discourage enrollment. States also could begin requiring substantial deductibles and co-payments, which could prove unaffordable for some poor beneficiaries, including people with serious medical conditions that are costly to treat. This could significantly reduce beneficiaries’ access to care.

- States facing shrunken block grant funding would likely scale back their provider reimbursement rates, which already are significantly lower than reimbursement rates under Medicare and private insurance and have been cut substantially in recent years by states coping with budget shortfalls. The Urban Institute estimated that the similar block grant in the House-passed budget from 2012 would likely result in reductions in reimbursements to health care providers and plans of more than 30 percent, on average, by 2022.[11] These reductions in provider reimbursement rates likely would apply not only to hospitals, nursing homes, physicians, and pharmacies but also to managed care plans that currently serve low-income children and their parents through Medicaid and CHIP.

Chairman Ryan criticizes Medicaid for its current low reimbursement rates, which he argues result in providers refusing to participate in Medicaid and in limited beneficiary access to needed care. Yet, his block grant proposal would very likely worsen the problem by leading to large cuts in provider reimbursement rates and thereby causing some existing providers and plans to stop serving low-income beneficiaries. That could jeopardize some beneficiaries’ access to care, particularly in communities that already are medically underserved, such as rural areas. It also would place greater pressure on providers such as community health care centers and safety net hospitals, which disproportionately serve Medicaid beneficiaries and would likely face substantially increased patient loads because of increased numbers of uninsured and underinsured individuals as a consequence of the Medicaid cutbacks.

House Budget Chairman Paul Ryan argues that his block grant proposal would reduce state fiscal burdens and allow states to tailor their Medicaid programs to better fit their needs and to provide Medicaid beneficiaries more choices and better access to care. Yet there is little question that the block grant proposal would result in severe cuts in federal funding for state Medicaid programs. To compensate for funding cuts of this magnitude, states would have little choice but to institute deep cuts to eligibility, benefit coverage, and/or provider payment rates (unless states were willing to come up with large new amounts of their own funding to replace all of the lost federal funds, which would be extremely unlikely). The almost-inevitable result would be that millions more low-income individuals and families would end up uninsured or underinsured, with reduced access to needed medical care, and millions more would lose coverage due to the budget’s repeal of the health reform law’s Medicaid expansion.