- Home

- Budgeting For The Future: Fiscal Plannin...

Budgeting for the Future: Fiscal Planning Tools Can Show the Way

Links:

Executive Summary

When state policymakers are writing a budget, they should be mindful of the future, not just the present. The state budget is the single most important document that a state government produces each year, and it receives close public scrutiny. It serves as both a financial plan and a policy document — that is, a description of the policies the state intends to pursue in the future. The spending, tax, and other policy decisions that comprise the budget have consequences for a state’s fiscal and economic security that last long beyond the budget year.

Often, however, policymakers focus on the immediate effects of policy decisions and fail to account for their longer-term consequences. Many states, for instance, fail to produce multi-year spending plans, fail to establish sound “rainy day funds,” and/or fail to follow best practices for forecasting revenues, spending commitments, pension obligations and the like. These are proven methods to improve long-term planning, yet they are underutilized.

This report describes the ten key tools that can help states chart their fiscal course accurately and make corrections when needed; it also surveys the 50 states and the District of Columbia on the degree to which they use these tools. It finds that the use of these tools cuts across regional and partisan divides. For instance, Connecticut, Maryland, and Tennessee incorporate most of the ten tools into their budget processes. New Jersey, Oklahoma, and South Dakota incorporate the fewest.

The timing is right for states to adopt a much more rigorous approach to their long-term budget planning. The fiscal crisis of the last few years prompted skepticism about states’ ability to fund public services such as education, health care, and infrastructure. The Great Recession — the most severe recession in seven decades — blasted holes in state budgets from which they have yet to fully recover. State tax revenues remain just below where they were five years ago (after adjusting for inflation) even as costs such as health care have risen faster than general inflation and the number of students, the elderly, and other state residents needing services has grown. Demographic changes such as the aging population are putting increasing pressure on state budgets, while the future course of health care costs, one of the largest parts of state budgets, remains unclear. Also, the federal government, which provides about one-quarter of state and local revenues, is on track to make deep spending cuts (under the 2011 Budget Control Act and sequestration) that could hit states hard.

Despite these fiscal challenges, state-funded services are essential to the nation’s economy and will remain so long into the future. State policymakers should be thinking hard about the future whenever they write a budget, because their decisions will have very big implications many years down the road. They should be asking: Is our state’s future workforce well-suited for the jobs of tomorrow? Will our infrastructure meet emerging needs? Is our tax system sufficiently up-to-date for the 21st century economy? And how will our budget choices today affect our ability to provide residents with a high quality of life for decades to come? Laying out a clear roadmap of the implications of the state budget — using proven, nonpartisan methodologies — can reduce uncertainty and help a state handle the outside shocks that will inevitably arise.

Specifically, to budget wisely for the future, every state needs:

- A map for the future: The budget and accompanying documents should include a detailed roadmap of the budget’s immediate and future impacts on the state’s fiscal health.

- Professional and credible estimates: Standards and sufficient oversight are needed to guarantee that these analyses of the budget’s impacts are professional, credible, and prepared without political influence.

- Ways to stay on course: Mechanisms should be in place to trigger any needed changes during the budget year, before too much damage is done.

These are achievable goals. Every state does these things to at least some extent. And a wide range of government budget experts agree they are needed (see box on page 5). But no state does them nearly as well as they could. The next sections outline the ten tools states should adopt for better fiscal planning.

Mapping the Future Impact of the Budget: Tools 1-3

We identified the ten tools in this report through a survey of existing reports and consultations with experts on state budget analysis. The most obvious first step toward sound long-term budget planning is that the budget should include a description of how today’s choices will affect the state’s future fiscal health. During the budget development process, a state can build in a focus on the long term by including revenue and spending projections for at least five years in its annual or biannual plan. These forecasts are most useful when they explain the trends they reveal. For example, they could examine such questions as: “Are debt service costs accelerating due to increased borrowing?” or “Is the design of the sales tax slowing revenue growth?” Producing regular projections forces the governor and legislators to confront the implications of their proposals for years beyond the upcoming budget. It also allows for a better informed debate by the public and outside observers.

States also should require, for bills that affect taxes or spending, timely and accessible fiscal notes that estimate the bill’s savings or costs for at least the upcoming five years.

States can further plan for the future by preparing a current services baseline, or projection of the cost of continuing to deliver the same quantity and quality of services as in the current budget period. This information allows the public and outside analysts to easily determine how proposed policy changes and program funding levels would affect public services. That, in turn, allows for more informed debates over the trade-offs required to balance the budget.

Ensuring That Projections Are Professional and Credible: Tools 4-6

It is not enough that long-term planning exists; it must also be based on credible, professional information so that it is not ignored. For example, states can depoliticize a critical part of the budget preparation process by creating a consensus revenue forecast, which is an agreement among the executive branch and both houses of the legislature on a revenue forecast for upcoming years. Another way to ensure that the fiscal plan is taken seriously is to establish a non-partisan, professional legislative fiscal office to provide a check on the information prepared by the executive branch.

Experts Agree on Need for Planning

A wide range of independent experts — including budgeting professionals, bond rating agencies, and academic researchers — have long recognized the importance of forecasting the potential impact of state tax and spending decisions for the long term. For example, eight of the major associations that represent elected officials and professional managers and finance professionals formed a commission called the National Advisory Council on State and Local Government Budgeting in 1999. The top of their list of recommended budget practices states, “A good budget process… incorporates a long-term perspective.”a Similarly, the head of the General Accounting Office listed “information about the long-term impact of decisions” as the first of four principles for the budget process in 2002 congressional testimony.b In addition, the criteria used by Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s,c major bond rating agencies, to determine the fiscal health of governments emphasize the importance of long-term planning.

These organizations — as well as the National Association of Budget Officers, various academics, and others that study public budgeting — all agree that planning ahead is important. They have also identified a number of mechanisms that states can use to carry out this planning. The budgeting tools most commonly identified are multi-year forecasts of base revenues and spending and the impact of changes in tax and spending policy, a consensus process for estimating revenues, rainy day funds, information on the cost of tax exemptions and credits, regular budget status reports, and oversight of debt levels and pension costs. In addition, some budget professionals recommend the use of current services baselines, independent legislative fiscal offices, and sunsets (expiration dates) for tax expenditures.

The ten tools that comprise the list of recommended tools in this report are drawn from this literature. CBPP also enlisted the help of state budget experts from the Rockefeller Institute of Government, the Council of State Governments, the National Association of State Budget Officers, and the Urban Institute to review the list of tools we compiled.d

- National Advisory Council on State and Local Budgeting, Government Finance Officers Association, “Recommended Budget Practices: A Framework for Improved State and Local Budgeting,” June 1999.

- United States General Accounting Office, Testimony before the Committee on the Budget, House of Representatives, Statement of Susan J. Irving, Director, Federal Budget Analysis, April, 25, 2002.

- See US States Rating Methodology, Moody’s Investor Service, April 17, 2013 and U.S. Public Finance: U.S. State Ratings Methodology, Standard & Poor’s, January 3, 2011.

- These experts agreed that these are important and useful mechanisms for state fiscal planning. They do not necessarily endorse each tool as required for each state to plan effectively

Pension costs are often cited as a concern for state budgets, and one key to reducing (or preventing) the accumulation of new, unfunded pension obligations is for a state to determine the level of contributions needed to state pension funds and make those contributions regularly. Because of the complexity this involves, regular reviews by independent authorities of the process used to determine pension contribution levels and underlying assumptions are necessary.

Ways to Stay On Course: Tools 7-10

The budget process is not over once the legislature adopts a budget. Some basic elements of a budget forecast, such as inflation, the state of the economy, or the makeup of the state’s population, cannot be known with certainty; even with the best methods, some assumptions will prove incorrect. A state must be able to manage revenues and spending throughout the year to deal with these uncertainties.

For example, when available revenues fall short of projected spending in the middle of the budget year due to a weak economy, adequate and well-designed rainy day funds can reduce the need for damaging service cuts and tax increases. But a state must fill its rainy day fund in good times to prepare for bad times. Formal deposit rules encourage states to make such deposits by making it harder to forgo deposits without attracting the notice of outside observers.

When recessions occur, states must scrutinize all forms of spending. An important tool for this is oversight of various tax expenditures (tax credits, deductions, and exemptions that reduce state revenue), which in many ways function as spending through the tax code. This will enable states to make sound choices between the most essential tax expenditures and those the state can forego. For example, states can regularly publish tax expenditure reports that list each tax break and its cost. And states can enact sunset provisions so that tax breaks expire in a specified number of years unless policymakers choose to extend them.

States also need tools for managing their long-term funding commitments. These include their pension obligations to retired state employees and their obligations to repay bonds that were issued to fund the construction of schools, roads, bridges, and other infrastructure. Because of the long-running and fixed nature of these obligations, it is particularly important that states regularly check whether they are meeting these obligations by establishing prudent rules on pension funding and debt levels. For example, states should make the full payment required each year to ensure that pension trust funds will be able to cover future costs — or should catch up quickly if they are temporarily unable to make the full payments. Also, to assure that debt service obligations remain affordable, states should establish guidelines for appropriate levels of debt relative to the size of a state’s economy.

In addition, a state must monitor the overall balance of the budget between revenues and spending throughout the year. No state will be able to predict all economic ups and downs or budget pressures and design a budget that addresses them all automatically. Regular revenue and spending status reports during the course of the fiscal year that combine revised revenue estimates with updated spending projections will shine a light on fiscal problems while there is time to correct them.

Ten Tools for Budgeting for the Future

Here are ten mechanisms states can use to inform long-term planning.

Does the Budget Provide a Map of the Future?

- Multi-year forecasts of revenues and spending: projections of revenues and current services spending for at least five years. These projections should be a regular part of the budget and should be detailed and easily accessible.

- Fiscal notes with multi-year projections: an established set of guidelines for preparing fiscal notes that estimate the savings, costs, or revenue changes for the current year and at least five future years. Estimates should be easily available.

- Current services baseline: a projection of how much it will cost a state in an upcoming budget period to deliver the same quantity and quality of services to residents that it is delivering in the current budget period, taking into account factors such as inflation, expected changes in the number of people utilizing those services, any previously enacted rule changes that have not yet phased in, and ongoing formula-based adjustments.

Are the Projections Professional and Credible?

- Independent consensus revenue forecast: a formal mechanism to create consensus among the executive and legislative branches on a revenue forecast.

- Legislative fiscal office: a non-partisan agency that analyzes the budget and other bills that affect spending and revenues.

- Pension oversight: regular reviews by independent authorities of methods used to determine future pension funding. These reviews should be published and easily accessible to the public.

Are Ways to Stay on Course in Place?

- Well-designed rainy day fund: a reserve fund designated for situations where state revenues drop or expenditures increase unexpectedly. These funds should not be capped at an inadequate level (below 15 percent of the state budget) and should be governed by rules that encourage deposits in good times and provide notice if deposits are skipped.

- Oversight of tax expenditures: expiration dates for tax expenditures after a set number of years to subject them to regular scrutiny of their cost and effectiveness, in addition to tax expenditure reports that list the costs of individual tax breaks.

- Pension funding and debt level reviews: recommended standards for pension funding and guidelines for the amount of debt that the state can incur.

- Budget status reports: regular reports by a professional fiscal authority on updated revenue and spending projections in order to determine if the budget is on track.

Rating the States

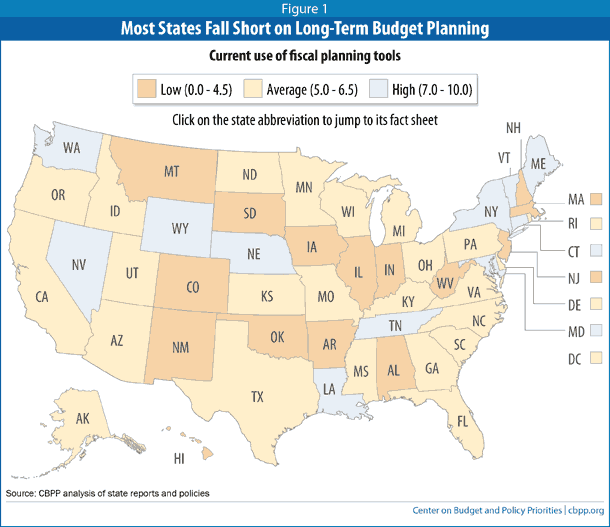

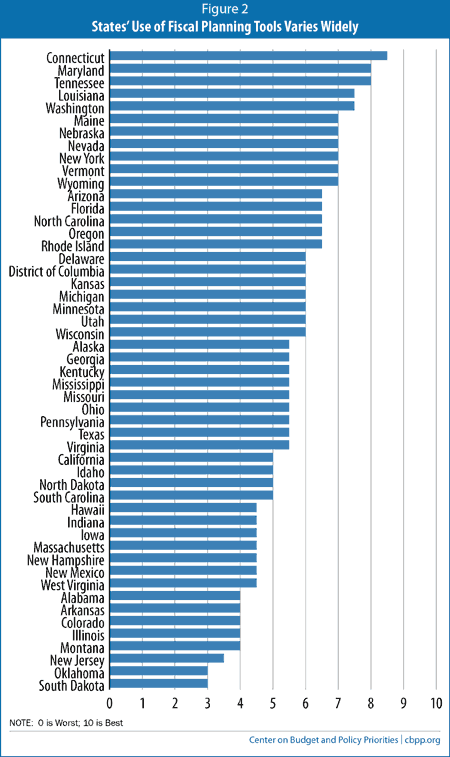

This report grades states on how well they have implemented the tools described above. We evaluated each state on its use of each tool and assigned a score on a simple scale: 0 if the state does not use this tool at all, 1/2 if it uses the tool but in a way that needs significant improvement, and 1 if the tool is in place, is well designed, and is accessible to the public.[1] Finally, we summed the scores on each of the individual tools to determine an overall score for each state on a scale of one to ten. Figures 1 and 2 show the results. (The District of Columbia is included in counts of states.)

Sound planning is not a partisan or a regional practice. (See Table 1.) For example, New York (the prototypical liberal northern state) and Louisiana (a southern state with a much more conservative bent) both do relatively good jobs of planning ahead, while there is much room for improvement in both Alabama and Massachusetts. These examples also show that the ability to look ahead does not dictate a particular set of tax or spending programs. Rather, it allows a state to see and plan for the future effects of whatever policy is being proposed, whether an expansion of assistance for low-income students or the elimination of a state’s income tax.

To read the full report, view the PDF here.

End Notes

[1] Accessible means that the analysis generated by the tool is summarized clearly and easily available to the public online, rather than an internal report.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work: