- Home

- Cuts Contained In SNAP Bill Coming To Th...

Cuts Contained in SNAP Bill Coming to the House Floor Would Affect Millions of Low-Income Americans

House Agriculture Committee Chairman Frank Lucas (R-OK) introduced legislation on September 16 setting forth the House Republican leadership’s proposal to cut SNAP (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as the food stamp program) by at least $39 billion over ten years. This is almost double the cut in the House Agriculture Committee farm bill and about ten times the SNAP cut in the Senate-passed farm bill.[1] The proposal is expected to go to the House floor this week.

The legislation (H.R. 3102) incorporates all of the SNAP cuts and other nutrition provisions of the farm bill that House leaders sought unsuccessfully to pass in June, which would cut $20.5 billion from SNAP over ten years.[2] It also adds new provisions designed to cut at least another $19 billion in benefits, primarily by eliminating states’ ability to secure waivers for high-unemployment areas from SNAP’s austere rule that limits benefits for jobless adults without children to just three months out of every three years.[3]

The House SNAP bill is harsh. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates it would deny SNAP to approximately 3.8 million low-income people in 2014 and to an average of nearly 3 million people each year over the coming decade. Those who would be thrown off the program include some of the nation’s most destitute adults, as well as many low-income children, seniors, and families that work for low wages. The people the bill would cut off SNAP include but are not limited to:

- 1.7 million unemployed, childless adults in 2014 who live in areas of high unemployment — a group that has average income of only 22 percent of the poverty line (about $2,500 a year for a single individual) and for whom SNAP is, in most cases, the only government assistance they receive (this number will average 1 million a year over the coming decade);[4]

- 2.1 million people in 2014, mostly low-income working families and low-income seniors, who have gross incomes or assets modestly above the federal SNAP limits but disposable income — the income that a family actually has available to spend on food and other needs — below the poverty line in most cases often because of high rent or child care costs. (This number will average 1.8 million a year over the coming decade.) In addition, 210,000 children in these families would also lose free school meals;

- Other poor, unemployed parents who want to work but cannot find a job or an opening in a training program — along with their children, other than infants.

| Table 1 Major SNAP Cuts in H.R. 3102 |

|||

| Provision | 10-year Cut | Number of Individuals Cut Off SNAP | |

| Fiscal Year 2014 | Average 2014 to 2023 | ||

| Cutting Off Unemployed Childless Adults Even When Jobs Are Scarce (Eliminates Waivers) (Sec. 109) | -$19 billion | 1.7 million | 1 million |

| Eliminating SNAP Eligibility That Is Based on “Expanded Categorical Eligibility” (Sec. 105) | -$11.6 billion | 2.1 million | 1.8 million |

| Encouraging States to End SNAP for Poor Families That Cannot Find Work (Southerland Amendment) (Sec. 139) | CBO has not estimated the effect on SNAP caseloads, benefits, or bonus payments to states. |

||

| Restricting a Simplification Option for Determining Household Benefit Levels (LIHEAP/SUA) (Sec. 107) | -$8.7 billion | N.A. | 850,000 households would lose an average of $90 a month |

| Other Provisions and Interactions (See Table 2, below) | $0.2 billion | N.A. | |

| Total | -$39.0 billion | At least about 3.8 million | At least about 2.8 million |

| Notes: Based on Congressional Budget Office letter to the Honorable Frank D. Lucas, September 16, 2013. | |||

See Table 1 for a summary of the bill’s major SNAP benefit cuts and Table 2, below, for the detailed CBO cost estimate of the bill.

Proponents’ rhetoric about the importance of work also overlooks the fact that most SNAP recipients who can work do so. More than 80 percent of SNAP households with at least one working-age, non-disabled adult worked in the year before or after receiving SNAP.[5]

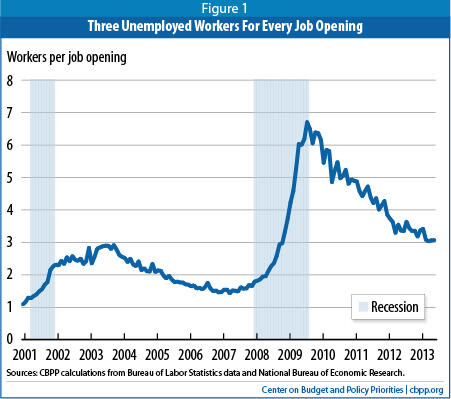

The proposed cuts would be on top of a substantial across-the-board benefit reduction for all SNAP households that takes effect in November. Benefits will be reduced, for example, by $36 a month for all families of four on SNAP (about $400 over the course of fiscal year 2014).[6] The proposed House cuts also come at a time when the economy continues to struggle to create sufficient jobs and the share of adults with jobs remains only slightly above the level to which it fell at the bottom of the recession. The economy is creating only 150,000 to 200,000 jobs a month, not much more than needed just to keep up with population growth. As Figure 1 shows, there are three unemployed workers for every job opening.

Though SNAP benefits are modest, at an average of less than $1.40 per person per meal,[7] SNAP is the nation’s foremost tool against hunger and severe hardship, particularly during recessions and periods of high unemployment. During the recent recession, SNAP performed as it was designed to: as millions of Americans lost their jobs and fell into poverty, SNAP responded to the increase in need, helping to avert the harshest impacts of the recession while also providing a boost to the economy.

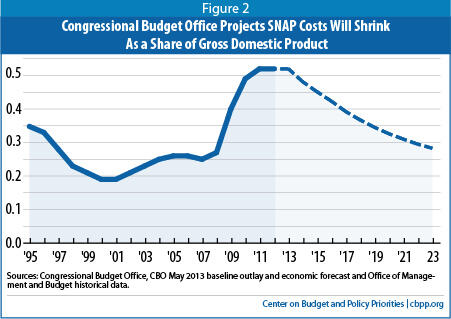

Growth in SNAP caseloads has slowed substantially in the past year. Of particular note, CBO projects that as the labor market recovers and employment improves, SNAP caseloads will fall and by 2019, SNAP costs will return to their 1995 level as a share of the economy.[8] (See Figure 2.) CBO also projects that SNAP costs will rise no faster than the economy over the long term, meaning that SNAP does not contribute to the nation’s long-term fiscal problems. This reality — along with a commitment to reduce deficits without increasing poverty — are reasons that the bipartisan Simpson-Bowles plan, the bipartisan Rivlin-Domenici plan, and the bipartisan Senate “Gang of Six” plan all contained nocuts in SNAP.

The impact of the proposed cuts on low-income communities, as well as on poor individuals, would be substantial. The increased demand on already-strained local services and charities would be large — either squeezing support for other needy residents or leaving many people who are cut off SNAP without sufficient food. Table 1 provides information about the state-by-state impacts of the proposed House cuts.

Cutting Off Unemployed Childless Adults Even When Jobs Are Scarce

To mitigate the provision’s impact when the economy is weak, the provision’s authors (two conservative House Republicans successfully offered it as an amendment on the House floor in 1996) designed it to allow states to request a temporary waiver from the three-month cut-off for areas with high unemployment. The authors highlighted the waiver authority in 1996 in insisting that the provision would not cause hardship.

To receive a waiver, states must provide detailed Labor Department unemployment data for areas within the state that demonstrate sustained levels of high unemployment. During the recent recession and its aftermath, which has featured continued high unemployment, most states — under governors of both parties — have sought and received waivers.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has approved waivers under a consistent and fixed set of rules and regulations for 16 years. Claims that the Obama Administration has expanded the waiver criteria or abused these rules, as House Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R-VA) clearly implies in the document he issued in late August that describes and promotes the new House SNAP proposal, are mistaken.[9] The Bush Administration used the same criteria to approve waivers as the Obama Administration has. Moreover, it was the Bush Administration that issued guidance making it possible for states to use eligibility for the federal Emergency Unemployment Compensation program to qualify for waivers.[10] (Rep. Cantor correctly noted that more states have received statewide waivers under the Obama Administration, but this is because unemployment has been much higher since 2009 and because more states qualified for temporary extended benefits under the Emergency Unemployment Compensation rules Congress enacted.)

Under the rules, the number of states eligible for such waivers is now declining, and all or nearly all statewide waivers will end as the labor market improves in the next few years. As a result, the number of childless adults receiving SNAP is likely to drop by 1 million to 2 million over the next few years under current law.

But the new legislation would eliminate the waiver authority, so it no longer could be used in areas that continue to have high unemployment — or in future recessions. The legislation would end the waiver authority immediately, which (in conjunction with other provisions in the bill) would terminate assistance for at least 1.7 million poor jobless individuals who live in high unemployment areas, even if they want to work and are looking hard for a job, but can’t find a job or a place in a work or training program. As noted above, states do not have to provide work or training slots for these individuals.

Current law does provide a modest incentive for states to offer a work program or training slot to people who can’t find a job. States that commit to providing a place in a work or job training program to all such individuals qualify for a share of $20 million in dedicated federal SNAP employment and training funds that are reserved for this purpose. Only a handful of states, however, avail themselves of these funds and offer a work or training slot to all of these individuals before cutting off their benefits after three months.

But the new legislation would end even this modest incentive. It eliminates the $20 million per year in dedicated job training funds for this population, which almost certainly would lead to even fewer states offering all of these individuals a work or training opportunity before cutting them off.

The legislation makes one other change in this area. Under current law, states may grant a limited number of individual exemptions from the three-month cut-off rule. Some states have used their available exemptions, but many other states have left many or all of their exemptions unused. The exemption authority has proven difficult and unappealing for many states to use, as the box, “Relying on Exemptions Provides a Misleading Defense,” below, explains. The new legislation somewhat increases the number of exemptions that states overall would be permitted to grant (although some states would receive fewer exemptions than under the current rules). But how many of these exemptions would actually be used is quite unclear, especially given the spotty record and limited use of the existing exemption authority by states over the past decade and a half.

Eligibility Cuts for Jobless Workers Could Affect 170,000 Low-Income Veterans

Substantial numbers of low-income veterans are among those who would be affected by the legislation. Census data indicate that approximately 900,000 veterans receive SNAP assistance each month. (This figure is almost surely understated, because Census data do not capture SNAP receipt by homeless veterans — who, like most other homeless individuals aren’t included in the Census survey — and understate the overall number of people receiving SNAP.)

An estimated 170,000 of those 900,000 veterans could be affected by the two provisions of the House proposal that would place food assistance for jobless workers at risk.

The first of these, the “Southerland” provision, would encourage states to terminate assistance to non-elderly jobless adults (and their families) who do not find work or an opening in a workfare or job training program. According to the Census data, about 120,000 veterans could be at risk of losing SNAP under this provision. The second is the provision that would require states to terminate food aid after three months to unemployed people aged 18 to 50 not raising minor children who live in areas of high unemployment and cannot find a job or a place in a work or job training program. According to the Census data, about 50,000 veterans could be at risk of losing SNAP under this provision.

Other cuts in the bill, including the “categorical eligibility” cut targeted at low-income working families with high housing or child care costs (described below), could affect additional veterans and their families.

Taken together, these changes to the provisions of SNAP law related to unemployed childless adults would cut benefits by $19 billion over the next ten years, according to CBO, and cut SNAP employment and training funds for these individuals by $200 million over 10 years.

Relying on Exemptions Provides a Misleading Defense

Current SNAP law allows states to provide exemptions to up to 15 percent of the estimated number of unemployed childless individuals in the state who would otherwise be terminated because of the three-month cut-off. The new legislation revises that authority by allowing states to exempt up to 15 percent of the number of jobless, non-disabled, and childless adults aged 18 to 50 who participated in SNAP in fiscal year 2011. Overall, this would result in a somewhat larger number of exemptions than are currently available, and the document released by House Majority Leader Eric Cantor in late August cites that to argue that the proposal’s elimination of the waiver authority would not cause serious hardship.

This portrayal, however, is misleading. The claim that the ability of states to provide these exemptions would prevent hardship and destitution in high unemployment areas that no longer would receive waivers is incorrect, for several reasons.

As noted, this is a very vulnerable population. Since the number of exemptions is very small compared to the number of people affected by the three-month cut-off provision and many of the affected individuals have similar circumstances — they are unemployed in a weak economy, struggling to make ends meet, and often facing destitution — it is difficult for states to determine which of those individuals should receive exemptions and which should not. A large share of these individuals fall into serious hardship categories such as being homeless or extremely poor (with income well below half of the poverty line), victims of domestic violence, having very low skills and limited education, or living in remote areas with limited transportation or employment opportunities.

Adding to this problem, states have found it administratively difficult to use the exemptions. Individual eligibility workers generally don’t know how many exemptions have been used in other parts of the state.

For these reasons, some states have not used these exemptions at all, while states that have used them generally have designed very narrow criteria that have resulted in large numbers of the exemptions not being used.

Moreover, during periods of high unemployment, the number of exemptions fails — by a large margin — to reflect current economic conditions and the lack of available jobs.

The bottom line is that the exemptions have not proved very effective in averting severe hardship — only the waivers for high-unemployment areas have. In any event, the number of exemptions allowed would be very small; even if fully used, the exemptions would leave six of every seven poor jobless workers without children who live in areas of very high unemployment with no protection at all.

CBO estimates that by eliminating states’ ability to waive the three-month cut-off for areas of high unemployment, the proposal would immediately subject 1.7 million poor jobless individuals to the three-month cut-off regardless of whether they want to work, are searching for a job, and are willing to take a job or participate in a training program. CBO assumes that states would broadly make use of the individual exemption authority despite not having done so in the past. If states instead follow their historic pattern and leave many exemptions unused, then the number cut off SNAP would be higher.

The numbers of people cut off in subsequent years would be somewhat lower, as many people who have relied on SNAP during the recession and weak recovery are expected to return to work in coming years as the labor market recovers more fully and more jobs become available. In addition, as discussed above, some waivers that have been in effect in the past few years because of widespread high unemployment will end in the years ahead, as unemployment recedes. As fewer areas qualify for waivers, many childless adults will be cut off SNAP even without the House Republican proposal to eliminate waivers; the three-month cut-off provision of current law is already tough. The average of 1 million people a year in high-unemployment areas whom CBO estimates would be cut off SNAP over the coming decade is the additional number of poor childless adults who will lose benefits, beyond those who already stand to be cut off in coming years under current law.

The individuals who would lose basic food assistance under the House provision are among the poorest people in the nation. While on SNAP they have monthly average incomes of just 22 percent of the poverty line, about $2,500 a year. For most of them, SNAP is the only state or federal income assistance available.

These individuals are a diverse group. More than 40 percent are women. One-third are over age 40. Among those who report their race, about half are white, a third are African American, and a tenth are Hispanic. Half have only a high school diploma or GED. They live in all areas of the country. Among those for whom metropolitan status is available, about 40 percent live in urban areas, 40 percent in suburban areas, and 20 percent in rural areas.

In addition to driving several million people off SNAP immediately, this provision would bar states from providing SNAP assistance to newly unemployed, childless workers in future recessions, no matter how high the unemployment rate climbs and how severe the downturn is.

Rep. Cantor claims the elimination of the waiver authority would “simply restore the intent of bipartisan reforms accepted in 1996.” In actuality, the opposite is true, as the House proposal would remove the waiver authority that was a key component of the 1996 law’s tough three-month limit on benefits for some of the nation’s poorest citizens.

Also misleading is the emphasis that Rep. Cantor places on the fact that New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg has declined to request a waiver. He fails to disclose that New York City is one of the few jurisdictions in the country that commits to offer a work program slot to all of these childless SNAP recipients, with the result that recipients are not cut off as long as they enter the City’s work program. States or jurisdictions within states that make the commitment are eligible for additional federal funds to assist them in fulfilling this commitment, though just $20 million per year is available to all “pledge states,” and the funds are allocated on a pro-rata basis. New York City is unusual in this regard; all but a handful of states and local jurisdictions have not adopted such a practice, and cut jobless people off after three months without offering most of them a place in a work program. To follow the New York example, the new legislation would need to provide significant new federal funding for SNAP employment and training to ensure that all individuals facing the time limit were offered an opportunity to participate in a qualifying work or training program, and would have to mandate that all states provide a work opportunity to all affected individuals. Instead, the legislation reduces SNAP funding for work and training programs for this population.

(For more information on this reported provision, see our paper, “House Republicans’ Additional SNAP Cuts Would Increase Hardship in Areas With High Unemployment,” https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=4001 and our infographic, “House SNAP Provision Would End Food Assistance To Needy Childless Unemployed Adults,” https://www.cbpp.org/files/9-10-13fa-factsheet.pdf.)

Eliminating SNAP Eligibility That Is Based on “Expanded Categorical Eligibility”

In addition to the provision described above, H.R. 3102 includes the SNAP and other nutrition provisions of the farm bill that House leaders unsuccessfully sought to pass in June. One of the most significant provisions in that package would terminate SNAP for another 2.1 million people in 2014 — and an average of 1.8 million people over the coming decade — by eliminating an option that allows states to extend benefits to certain low-income households who have gross incomes or assets modestly above federal SNAP limits, particularly low-wage working families and certain low-income elderly individuals.[11] Most of the $11.6 billion in benefit reductions from this provision would come from eliminating SNAP benefits for workinghouseholds or seniors. In addition, 210,000 children in low-income families whose eligibility for free school meals is tied to their receipt of SNAP would lose free school meals when their families lose SNAP benefits.[12]

By themselves, SNAP’s gross income test and outdated asset test deny eligibility to many low-income families who face significant difficulties making ends meet:

- Under standard SNAP rules, a household’s gross income must be at or below 130 percent of the poverty line. This limit excludes some low-income working families whose gross income exceeds 130 percent of the poverty line but whose disposable income — the amount of income the family has that is available to spend on food — is below the poverty line, often because the family must incur sizeable child care costs in order to work or faces very high housing costs that consume the majority of its income.

- In addition, under standard SNAP rules, a household must not have more than $2,000 in assets. This limit has not been adjusted for inflation in more than 27 years and has fallen 53 percent in real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) terms since 1986. In some states, a household that owns a car with a market value of $6,750 would exceed the asset limit, even if the household has little equity in the car, needs the car to get to work (especially in rural areas), and has virtually no savings or other assets.

The 1996 welfare law allows states to align their SNAP gross income limit and asset test with the eligibility rules they use in programs financed by the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant. Over 40 states have taken this option, known as expanded (or broad-based) categorical eligibility, to align program rules, simplify programs, cut administrative costs, and broaden SNAP eligibility to certain families in need, primarily low-wage working families with high expenses for costs such as child care. This option does not result in households being enrolled automatically; households must still apply through the regular SNAP application process, which has rigorous procedures for documenting applicants’ income and circumstances.

A typical working family that qualifies for SNAP due to categorical eligibility consists of a mother with two young children who has monthly earnings just above the program’s monthly gross income limit ($2,069 for a family of three in 2013). On average, the families above that limit who qualify for SNAP as a result of categorical eligibility have combined child care and rent costs thatexceed half of their wages. The approximately $100 per month in SNAP benefits they receive covers about one-fourth to one-fifth of their monthly food budget.[13]

(For more information on the provision to restrict the categorical eligibility option and other provisions in the House Agriculture Committee’s farm bill, see “House Agriculture Committee Farm Bill Would Cut Nearly 2 Million People Off SNAP,” https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3965.)

Encouraging States to End SNAP for Poor Families That Cannot Find Work

Section 139 of the Lucas bill would allow states to cut off SNAP benefits to most adults who are receiving or applying for SNAP, including parents with children as young as 1 year old, if they are not working or participating in a work or training program for at least 20 hours a week. This provision, based on an amendment to the original House farm bill offered by Rep. Steve Southerland (R-FL), authorizes states to cut off an entire family’s food assistance benefits, including their children’s — and for an unlimited time — if the parents do not find a job or job training slot.[14]

The provision gives states a strong financial incentive to take up this option. First, they could keep half of the federal savings from cutting people off SNAP and use the funds for any purpose, including tax cuts and special-interest subsidies or plugging holes in state budgets.[15] Second, states that decline the option and maintain their current approach to SNAP work requirements and job training would face a significant fiscal penalty. States that do not elect the option would lose all federal matching funds for their SNAP employment and job training programs (which all states now operate). States such as California, New York, New Jersey, and Illinois that currently run robust SNAP employment and training programs would face the stark choice of substantially altering their current programs (including the target groups of recipients they serve and the employment and training services they provide) in order to satisfy the new federal prescriptions, or losing all federal matching funds. In short, while billed as a state option or (even more misleadingly) as a “pilot” project, this part of the House bill is designed to coerce most states into adopting the harsh new regime.

Moreover, the provision provides no jobs, no work or workfare programs, and no additional funds for work or training slots. In fact, the bill would restrict existing SNAP work program and job training funds. (States that adopt this approach would have access to a pro-rata share of up to $277 million annually in federal matching funds for the costs of employment and training services and related transportation and dependent care costs. That, however, is approximately the amount of federal matching funds that states currently receive for SNAP employment and training programs. Moreover, the current matching funds are not capped at $277 million and rise as the costs of these state programs increase due to inflation and related factors. By capping this funding at $277 million, H.R. 3102 thus would reduce this funding over time, even as its proponents speak of placing more emphasis on work.)

The Southerland amendment requires states to include, on paper, an “intent” to provide job training or work slots to individuals subject to these requirements, but states would not be legally obligated to actually do so before cutting off households for failing to find work. Instead, states could demand that households with less than 20 hours per week of work increase their work hours or find a job training slot on their own that meets the states’ requirements. If households — even those who are actively searching for work and are on a waiting list for a job training program — are unable to fulfill this requirement, they could lose their SNAP benefits.

Other employment and training programs could not absorb large numbers of new participants. Federal programs funded under the Workforce Investment Act (WIA) are capped and have already been subject to cutbacks in recent year under sequestration. At least 48 states have waiting lists for WIA services for adults, and the number of individuals on waiting lists for adult education services doubled between 2008 and 2010.[16] The share of low-income individuals who receive intensive and training services through WIA has declined substantially in recent years. Moreover, WIA has no income eligibility limits, and its incentives discourage programs from serving the most disadvantaged workers. Most of the people who receive intensive or training services through WIA are not low-income adults.

The large new federal cash payments that states could receive — 50 percent of the federal savings from shrinking state SNAP caseloads via this provision — would be based solely on the overall reduction in the number of low-income households receiving food assistance, not on states’ success in helping unemployed individuals find and retain employment.

Claims About TANF’s Success Rely on Old Data and Omit Key Findings

House Majority Leader Eric Cantor asserts in the document he issued in late August describing and promoting the new House SNAP proposal that the experience of the 1996 welfare law demonstrates the proposed SNAP work provisions will benefit poor individuals and families, rather than subject them to hardship. Rep. Cantor’s arguments rely, however, on outdated and highly selective use of data that omits key research findings and facts.

Rep. Cantor notes that the number of children living in poverty — as well as the number in “severe poverty” (i.e., below half of the poverty line) — fell between 1995 and 2001. It attributes this largely to the 1996 welfare law. Yet this improvement reflected, in significant part, the sharp decline in the unemployment rate and the robust increase in real wages — including wages at the bottom of the wage scale — that occurred during this period, when the unemployment rate plunged to 4 percent.

Rigorous academic research has found that the improvements in employment rates and economic well-being among low-income families in these years also reflected large expansions in the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which drew more single parents into the labor force. A highly regarded study by University of Chicago economist Jeffrey Grogger found that the EITC expansions accounted for 34 percent of the growth of employment among single parents between 1993 and 1999, and the economy accounted for 21 percent of this growth, while the welfare law accounted for 13 percent.

Rep. Cantor also ignores the data since 2001. He fails to mention that employment gains among single mothers with a high school education or less began to erode after 2001, or that the percentage of single mothers who were employed in 2011 (the latest year for which these data are available) was lower than the percentage employed in 1996.

The brief period that Rep. Cantor uses to tout the welfare law’s unvarnished success was one in which the country witnessed an extraordinarily strong labor market. The unemployment rate of 7.4 percent in July 2013 stands in sharp contrast to the 5.1 percent unemployment rate the country witnessed in August 1996 when the welfare law was enacted — and in sharper contrast to the strikingly low 3.9 percent unemployment rate the country witnessed in the last quarter of 2000, when employment among single mothers peaked.

Rep. Cantor also ignores important academic research findings that, while the welfare law contributed to an increase in employment among some single mothers, it led to an increase in severe poverty among others, especially after the economic boom of the late 1990s faded. A recent study by researchers H. Luke Shaefer of the University of Michigan and Kathryn Edin of Harvard finds that the number of families with children living in extreme poverty — on less than $2 per person per day, a standard the World Bank uses to measure poverty in third-world countries — shot up by 159 percent between 1996 and 2011. The study identifies provisions of the 1996 welfare law that greatly constricted cash assistance, and thereby led to an increase in the number of single-parent families with neither cash assistance nor earnings, as a key factor behind this development.

Finally, Rep. Cantor glosses over the fact that in crafting the welfare law in 1995 and 1996, House Ways and Means Republicans sought to deflect criticisms that it would lead to serious hardship by emphasizing that food stamps would remain as a safety net and serve as a floor under poor families with children who might lose cash assistance benefits under the welfare law.

Millions of low-income adults and children live in households that could be affected by the Southerland provision. The households that could be affected have very low incomes, averaging 42 percent of the poverty line, or $8,200 for a family of three. For many such families, SNAP benefits stand between them and destitution.[17]

Some support for the Southerland provision appears to reflect the mistaken beliefs that SNAP has no work requirements and most SNAP recipients are not willing to work. In reality, SNAP has a very tough three-month time limit on receipt of SNAP benefits by unemployed childless adults (see above), and states can already require both childless adults and adults with minor children to search for work, accept a job offer, and participate in other employment and training programs or else lose their benefits. In addition, as noted, most SNAP recipients who can work do so: more than 80 percent of SNAP households with at least one working-age, non-disabled adult worked in the year before or after receiving SNAP.

(For more information on this provision, see our paper, “House Farm Bill Provision Would Pay States to Cut Families Off SNAP Who Want to Work But Cannot Find a Job,” https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3988.)

Restricting a Simplification Option for Determining Household Benefit Levels

Section 107 of the Lucas bill would restrict states’ ability to use an important program simplification that reduces paperwork burdens in determining household benefit levels. Based on CBO estimates, this provision would reduce benefits for about 850,000 households with 1.7 million people (most of whom reside in 15 states), with these households’ benefits cut by an average of about $90 a month. (Table 1 lists the 15 states.) This produces an $8.7 billion benefit reduction over ten years. The households affected by the cut would disproportionately be low-income seniors, people with disabilities, and working-poor families with children.

Under current SNAP rules, households with high housing (including utility) costs receive larger SNAP benefits since they have less income remaining for food. It can be time consuming for caseworkers and families to try to determine a household’s actual utility costs, which fluctuate from month to month. So, to simplify program administration, states can use a standard utility allowance (SUA) — reflecting typical low-income households’ utility bills in the state — as a proxy for the precise and varying amounts paid for utilities by individual households that pay for utilities separately from their rent.

In a related simplification, states can provide the SUA to households that receive energy assistance through the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP). For several decades, SNAP households that receive LIHEAP have been eligible for the SUA, based on the LIHEAP program’s determination that such low-income households have energy bills they need assistance in meeting.

In recent years, some states have provided a nominal LIHEAP benefit of $1 to $5 to many SNAP households to qualify them for the SUA, which in turn qualifies them for higher SNAP benefits. Some low-income households that pay utilities through their rents, rather than directly, have received these nominal LIHEAP benefits and consequently received a larger SNAP deduction for their housing costs.

The farm bills that the Senate passed this year and last — as well as the farm bill the House Agriculture Committee passed last year — took a targeted approach to addressing this issue and ending use of the SUA for households that receive these nominal LIHEAP benefits. This year’s House SNAP SUA proposal, however, takes a blunter approach and goes further than is needed to curb the practice some states have used of providing nominal LIHEAP payments to households that don’t actually incur out-of-pocket heating or cooling costs. In so doing, the House provision doubles the benefit cut in this area relative to last year’s bills and this year’s Senate bill.

Other Provisions

The legislation also contains other provisions included in the original House Agriculture Committee farm bill or added on the House floor that would cut SNAP in additional ways. See Table 2 for more detail on the CBO cost estimate of these provisions.

-

Eliminating incentive payments to improve program administration. The bill would eliminate payments established on a bipartisan basis in 2002 to encourage states to reduce payment errors and improve their performance in serving to low-income families. Because SNAP’s previous system for measuring state performance only assessed states’ payment accuracy, it had the unintended effect of rewarding a number of states that made it harder for eligible working-poor families to receive SNAP, because those states’ error rates were lower than other states’. (It is harder for states to determine SNAP benefit levels for working families with precise accuracy because their incomes fluctuate depending on their hours of work, loss of work due to sick days, etc.) The states, the Bush Administration, and Congress worked together in 2002 to build a more balanced accountability system.

The system they developed remains the most rigorous of any federal benefit program; it encourages states to improve both program integrity and overall SNAP operations. Performance bonuses are available to the top and the most improved states across four measures. The success of the system is reflected in the decline in SNAP error rates: the percentage of SNAP benefits that are overpaid in error fell to just 2.77 percent in 2012. Nevertheless, the House proposal would eliminate these performance incentives.

-

Permanently denying SNAP to certain ex-offenders. A provision of the original House bill, offered by Rep. Tom Reed (R-NY), would bar anyone from SNAP for life who is convicted of one of a specified list of violent crimes after the bill’s enactment, regardless of whether the individuals have served their sentences and complied with all terms of release, probation, and parole.

This provision, by making it harder for ex-offenders to reintegrate into society, could contribute to recidivism; ex-offenders often have difficulty finding jobs that pay decent wages. The provision would also affect children and other family members, as it would reduce the family’s food resources and squeeze the family’s food budget.

Waving the Fraud, Waste, and Abuse Flag

Over the years, policymakers seeking to cut assistance provided by various programs targeted on low-income households often have portrayed the programs as riddled with fraud and abuse, irrespective of what the data may show. Rep. Cantor continues this tradition in his description of the House SNAP proposal.

Contrary to Rep. Cantor’s depiction of the program, SNAP has one of the lowest error and overpayment rates of any large program, as a result of substantial improvements in, and tightening of, program administration over a number of years. The data from what is one of the most extensive and rigorous quality control systems of any program show that:

- The SNAP overpayment rate — the percentage of benefits either issued to ineligible households or overpaid to eligible households — was 2.77 percent in 2012. This includes overpayments due to unintended errors made by either recipients or caseworkers and overpayments due to fraud.

- The SNAP underpayment rate — the percentage of benefits that should have provided to eligible participating households but weren’t paid due to errors — stood at 0.65 percent. As a result, the net loss to the government — the overpayment rate minus the underpayment rate — is about 2 percent of benefits.

- By contrast, the rate of error and fraud in the federal income tax system equals about 15 percent of taxes legally owed. That is, about 15 percent of the income taxes that are owed go unpaid. (The percentage is even higher for certain types of taxpayers, such as farmers and small business owners.)

-

Cutting funding for nutrition education. The proposal would cut funding for SNAP’s nutrition education program (SNAP-Ed), which promotes healthy eating choices among low-income households. Under the bill, SNAP-Ed’s fiscal year 2014 funding would be reduced by $29 million, from $401 million to $372 million, and by $308 million over ten years. This proposed future funding cut comes on the heels of the program’s fiscal year 2013 budget cut of 28 percent.

With an average benefit of less than $1.40 per person per meal, SNAP participants face difficult economic choices at the grocery store, where less nutritious food is often cheaper than healthier options. SNAP-Ed works to improve low-income individuals’ knowledge and skills related to making healthy food choices, stretching food budgets, and preparing nutritious meals. Cutting these funds compromises states’ ability to run adequate-size nutrition education programs.

- A few small positive provisions. The bill contains a few positive provisions of small size, amounting to about $550 million over ten years, a little more than 1 percent of the $39 billion in cuts. For example, the bill would provide $50 million in new funding to enhance the Agriculture Department’s efforts to prevent retailers from accepting SNAP benefits for non-food items and $333 million in increased funding for food banks. For information on these provisions, see our paper: “House Agriculture Committee Farm Bill Would Cut Nearly 2 Million People Off SNAP,” https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3965.

Conclusion

SNAP reflects the nation’s commitment to reducing hardship and helping to ensure that poor Americans — including parents who are out of work and their children — can afford food. It also functions as a “work support” that helps low-income working families whose wages aren’t sufficient to make ends meet. Deep cuts to the program will compromise SNAP’s ability to help low-income Americans meet their basic food needs.

Critics’ attempts to justify big cuts by claiming that SNAP participants are eschewing work are unfounded. The fact that the majority of SNAP households with an adult who is not elderly or disabled work while they receive SNAP assistance, and that more than 80 percent of such households work in the year before or after SNAP receipt, makes clear the program is an important support for working families that fall on hard times.

As the nation slowly climbs out of the deepest recession in decades, many families continue to face a shortage of jobs or to be paid wages too low to enable them to provide adequate food, and struggle to meet basic nutritional needs. The House SNAP proposal pays little heed to these economic conditions. Instead, it would deny food assistance to millions of low-income Americans and cause substantial increases in hardship.

| Table 2 CBO Estimate of SNAP Cuts in H.R. 3102 |

|

| Provision | 10-year Cost Estimate (Outlays, in millions) |

| SNAP Benefit Cuts | |

| Cutting off unemployed childless adults even when jobs are scarce (eliminates waivers) (Sec. 109) | -$19,000 |

| Eliminating SNAP eligibility that is based on “expanded categorical eligibility” (Sec. 105) | -$11,555 |

| Encouraging states to end SNAP for poor families that cannot find work (Southerland amendment) (Sec. 139) | $4 (Employment and training and evaluation changes only)[19] |

| Restricting a simplification option for determining household benefit levels (LIHEAP/SUA) (Sec. 107) | -$8,690 |

| State option for drug testing applicants (Sec. 136) | -$35 |

| Eliminating eligibility for certain convicted felons (Sec. 137) | -$21 |

| Expungement of unused SNAP benefits (Sec. 138) | -$95 |

| Interactions | $715 |

| Subtotal, SNAP benefits | -$38,677 |

| Other SNAP Cuts | |

| Eliminating incentive payments (Sec. 119) | -$480 |

| Cutting SNAP nutrition education (Sec. 128) | -$308 |

| Retailer equipment (Sec. 102) | -$79 |

| Subtotal, Other SNAP Cuts | -$867 |

| Other Nutrition | |

| Increasing funding for emergency food assistance (Sec. 127) | $333 |

| Employment and training pilots (Sec. 123) | $30 |

| Adding resources to address retailer trafficking (Sec. 129) | $50 |

| Assistance for community food projects (Sec. 126) | $100 |

| Northern Marianas pilot program (Sec. 132) | $33 |

| Subtotal, Other Nutrition | $546 |

| Total H.R. 3102 | -$38,998 |

| Notes: Based on Congressional Budget Office letter to the Honorable Frank D. Lucas, September 16, 2013. | |

| Table 3 State-by-State Impact of SNAP Cuts in House Proposal |

||||

| State/Territory | Number of SNAP Participants Aged 18-50, Not Raising Minor Children, and Not Employed at Least 20 Hours Per Week* | Has the State Adopted the Expanded Categorical Eligibility Option?** |

Affected by House Standard Utility Allowance Change | |

| Asset Test | Income Test | |||

| Alabama | 74,000 | Yes | ||

| Alaska | 10,000 | |||

| Arizona | 96,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| Arkansas | 43,000 | |||

| California | 346,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| Colorado | 28,000 | Yes | ||

| Connecticut | 41,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Delaware | 11,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| District of Columbia | 22,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Florida | 414,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| Georgia | 168,000 | Yes | ||

| Guam | 1,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| Hawaii | 16,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| Idaho | 18,000 | Yes | ||

| Illinois | 182,000 | Yes | ||

| Indiana | 66,000 | |||

| Iowa | 34,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| Kansas | 27,000 | |||

| Kentucky | 88,000 | Yes | ||

| Louisiana | 71,000 | Yes | ||

| Maine | 27,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Maryland | 77,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| Massachusetts | 64,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Michigan | 212,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Minnesota | 41,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| Mississippi | 52,000 | Yes | ||

| Missouri | 88,000 | |||

| Montana | 12,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| Nebraska | 10,000 | Yes | ||

| Nevada | 31,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| New Hampshire | 8,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| New Jersey | 59,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| New Mexico | 32,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| New York | 211,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| North Carolina | 165,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| North Dakota | 3,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| Ohio | 163,000 | Yes | ||

| Oklahoma | 47,000 | Yes | ||

| Oregon | 120,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pennsylvania | 124,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Rhode Island | 14,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| South Carolina | 95,000 | Yes | ||

| South Dakota | 7,000 | |||

| Tennessee | 159,000 | |||

| Texas | 109,000 | Yes | Yes | |

| Utah | 23,000 | |||

| Vermont | 8,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Virginia | 68,000 | |||

| Virgin Islands | 1,000 | Yes | ||

| Washington | 124,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| West Virginia | 25,000 | Yes | ||

| Wisconsin | 71,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wyoming | 2,000 | |||

| United States | 4,000,000 | 43 | 27 | 15 |

| *These estimates, based on the latest available data, are for fiscal year 2011. The current figures may be different because of changes in the number of individuals who are eligible for and apply to participate in SNAP and in state eligibility for, and take-up of, waivers from the three-month cut-off. CBO estimates that 1.7 million individuals in fiscal year 2014 would lose SNAP because of the elimination of waivers for high unemployment areas and related provisions. Under CBO’s assumptions, the number losing eligibility would average 1 million over the decade. CBO’s estimates of the number of people losing SNAP as a result of these provisions is lower than the 4 million shown here primarily because CBO assumes that the number of such individuals who will otherwise participate in SNAP in future years is significantly lower than the number who participated in 2011 (due to an improving economy and because fewer areas will qualify for and/or request waivers under current law.) In addition, CBO assumes states will make broad use of their authority to exempt a small share of such individuals, despite not having done so in the past. We are not able to estimate the state-by-state shares of the reduction that CBO projects in the number of childless adults who would receive SNAP nationally as a result of H.R. 3102. **These states have adopted broad-based categorical eligibility. Additional states have narrow categorical eligibility (beyond cash assistance, but not affecting large numbers of households) and may also have some households that would be cut off SNAP. Sources: USDA, Food and Nutrition Service, Broad-based Categorical Eligibility Chart, and private correspondence. CBPP analysis of the 2011 USDA data on SNAP Household Characteristics. See http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/rules/Memo/BBCE.pdf and http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/government/program-improvement.htm. |

||||

House Agriculture Committee Farm Bill Would Cut Nearly 2 Million People Off SNAP

End Notes

[1] The legislation embodies the proposal put forward in late August by Majority Leader Eric Cantor in a document entitled “Background on The Nutrition Reform and Work Opportunity Act.” The September 16, 2013 CBO cost estimate is available at http://www.cbo.gov/publication/44583.

[2] The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the nutrition provisions of the farm bill brought to the House floor in June would save $20.5 billion over 10 years. This estimate does not include the additional savings from various amendments adopted in June on the House floor; CBO did not issue an estimate of the nutrition title of the bill with the amendments.

[3] For more detailed information on these provisions, see Dorothy Rosenbaum and Stacy Dean, “House Agriculture Committee Farm Bill Would Cut Nearly 2 Million People Off SNAP,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised May 16, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3965; Ed Bolen, Stacy Dean, Robert Greenstein, and Dorothy Rosenbaum, “House Farm Bill Provision Would Pay States to Cut Families Off SNAP Who Want to Work But Cannot Find a Job,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 9, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3988; and Ed Bolen, Dorothy Rosenbaum, and Robert Greenstein, “House Republicans’ Additional SNAP Cuts Would Increase Hardship in Areas With High Unemployment,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 7, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=4001.

[4] The bill’s provisions removing the ability of states to secure waivers for high-unemployment areas from a rule that cuts off benefits after three months for unemployed adults who aren’t raising minor children would, by itself, terminate benefits to more than 2 million individuals in 2014. The proposal also would retain and modify a provision of current law allowing states to exempt a modest fraction of these individuals from the benefit cut-off. CBO estimates the number people cut off in 2014 once these exemptions are taken into account to be 1.7 million. See “Cutting Off Unemployed Childless Adults Even When Jobs Are Scarce,” below, for a discussion of these issues.

[5] Dorothy Rosenbaum, “The Relationship Between SNAP and Work Among Low-Income Households,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 29, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3894.

[6] Stacy Dean and Dottie Rosenbaum, “SNAP Benefits Will Be Cut for All Participants in November,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Revised August 2, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3899.

[7] This level is currently close to $1.50 per person per meal but will drop to less than $1.40 on November 1.

[8] Chad Stone, Jared Bernstein, Arloc Sherman, and Dorothy Rosenbaum, “SNAP Enrollment Remains High Because the Job Market Remains Weak,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 30, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3996.

[9] See Majority Leader Cantor’s document entitled “Background on The Nutrition Reform and Work Opportunity Act,” which was distributed to House Republican staff the last week of August.

[10] See Food and Nutrition Service Guidance at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/rules/Memo/2009/010809.pdf.

[11] Individuals impacted by the proposal to restrict categorical eligibility have very little overlap with those that would lose eligibility from the proposal to eliminate waivers from the three-month time limit. As a result, the number of people impacted by the provisions is essentially additive.

[12] Dorothy Rosenbaum and Stacy Dean, “House Agriculture Committee Farm Bill Would Cut Nearly 2 Million People Off SNAP,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Revised May 16, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3965.

[13] Based on CBPP analysis of SNAP quality control administrative data for 2011 regarding households whose incomes exceed the federal SNAP limit but qualify for SNAP because of categorical eligibility. The analysis excludes the effects of the 2009 Recovery Act’s SNAP benefit increase because that increase will already have expired during all but one month of the 2014-2023 budget period.

[14] There are a few mostly technical differences between the provision included here and the Southerland amendment that passed the House in June. The most notable difference is that under H.R. 3102, individuals with disabilities would be exempt from the new requirements.

[15] CBO’s estimates of a $4 million cost over 10 years for this provision includes only the impacts of the provision on federal SNAP employment and training funds and the $1 million a year the bill provides for an evaluation. The estimate does not include any impact on the number of SNAP participants, SNAP benefits, or the “bonus” payments to states. CBO’s estimate of the employment and training changes appears to assume that some or all states take up the Southerland option.

[16] National Council of State Directors of Adult Education, “Adult Student Waiting List Survey, 2009-2010.”

[17] These figures exclude households without children, i.e., childless, unemployed adults. If they are included, average annual income is even lower.

[18] The underpayment rate was 0.65 percent for a combined error rate of 3.42 percent.

[19] CBO has not yet completed an estimate of the effect of the provision on SNAP participation, benefits, or the bonus payments to states. The impact of the provision could only increase the SNAP cuts in the bill.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise