- Home

- House Agriculture Committee Farm Bill Wo...

House Agriculture Committee Farm Bill Would Cut Nearly 2 Million People Off SNAP

On May 15, the House Agriculture Committee passed its 2013 farm bill, H.R. 1947 (the Federal Agriculture Reform and Risk Management Act of 2013, or FARRM).[1] The bill would cut the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as the Food Stamp Program) by almost $21 billion over the next decade, eliminating food assistance to nearly 2 million low-income people, mostly working families with children and senior citizens. The bill as a whole would reduce total farm bill spending by an estimated $39.7 billion over ten years, so more than half of its cuts come from SNAP. The SNAP cuts are more than $4 billion larger than those included in last year’s House Agriculture Committee bill (H.R. 6083).[2]

The bill’s SNAP cuts would come on top of an across-the-board reduction in benefits that every SNAP recipient will experience starting November 1, 2013. On that date, the increase in SNAP benefits established by the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act (ARRA) will end, resulting in a loss of approximately $25 in monthly SNAP benefits for a family of four. Placing the SNAP cuts in this farm bill on top of the benefit cuts that will take effect in November is likely to put substantial numbers of poor families at risk of food insecurity.

The majority of the bill’s SNAP cuts come from eliminating a state option known as “categorical eligibility.” Congress created this option in the 1996 welfare law, allowing states to provide food assistance to households — primarily low-income working families and seniors — that have gross incomes or assets modestly above federal SNAP limits but disposable incomes in most cases below the poverty line. The bill also would eliminate SNAP incentive payments to states that have improved payment accuracy and service delivery, would cut nutrition education funding, and would curtail a state option that reduces paperwork for many households with utility expenses and also lowers state administrative costs. Table 1 provides information about the effects of the provisions in specific states.

The proposed cuts would cause significant hardship to several million low-income households.

- The bill would terminate SNAP eligibility for several million people. By eliminating the categorical eligibility state option, which over 40 states have adopted, the bill would cut nearly 2 million low-income people off SNAP.

- Several hundred thousand low-income children would lose access to free school meals. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), 210,000 children in low-income families whose eligibility for free school meals is tied to their receipt of SNAP would lose free school meals when their families lose SNAP benefits.

- Some working-poor families would lose access to SNAP because they own a modest car, which they often need to commute to their jobs, especially in rural areas. Eliminating categorical eligibility would cause some low-income working households to lose benefits simply because of the value of a modest car they own. Many of these families would be forced to choose between owning a reliable car and receiving food assistance to help feed their families.

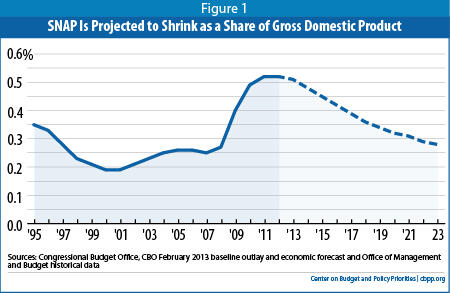

Contrary to proponents’ claim that the bill’s SNAP cuts are needed to rein in out-of-control program growth, CBO has found that SNAP’s expansion in recent years is primarily due to the severe and prolonged economic downturn and that SNAP spending will fall significantly as the economy recovers. CBO projects that the share of the population that participates in SNAP will fall back to 2008 levels in coming years and that SNAP costs as a share of the economy will fall back to their 1995 level by 2019.

Ending “Categorical Eligibility” State Option Would Cut Off SNAP Assistance For 2 Million People

The House Agriculture Committee bill achieves almost 60 percent of its SNAP cuts ($11.6 billion of the $20.5 billion in cuts over ten years) from eliminating the longstanding categorical eligibility option, which would primarily hit low-wage working families with children and low-income elderly individuals.

The 1996 welfare law allowed states to align their SNAP gross income eligibility limit and asset test with the eligibility rules they use in programs financed under their Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant. Over 40 states have taken this option, known as expanded (or broad-based) categorical eligibility, to align program rules, simplify their programs, reduce administrative costs, and broaden SNAP eligibility to certain families in need, primarily low-wage working families.

The federal SNAP gross income limit of 130 percent of the poverty line excludes some low-income working families whose disposable income is below the poverty line, often because they must incur sizeable child care costs in order to work. In addition, the SNAP asset limit of $2,000 has not been adjusted for inflation in more than 25 years and has fallen 53 percent in real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) terms since 1986. Some states use the categorical eligibility option to enable households with gross incomes modestly above 130 percent of the poverty line but disposable incomes below the poverty line — or savings modestly above $2,000 — to qualify for SNAP assistance, in recognition of their need.

The Lottery Winner Issue

An extremely unusual situation developed a couple of years ago in Michigan, where two low-income individuals who won the lottery continued receiving SNAP under Michigan’s rules. This should not be allowed, and the bill contains a separate provision prohibiting lottery or gambling winners from qualifying for SNAP. This rare and extreme case provides no basis for eliminating categorical eligibility, as it can readily be addressed without doing so.

-

The cut would push large numbers of low-income people off SNAP. CBO estimates that repealing categorical eligibility would eliminate food assistance to 1.8 million low-income people. Most of those who would lose eligibility are either low-income working families with children or seniors.

A typical working family that qualifies for SNAP benefits due to categorical eligibility is a mother with two young children who has monthly earnings just above the program’s monthly gross income limit ($2,069 for a family of three in 2013). On average, the families above that limit who qualify for SNAP as a result of categorical eligibility have combined child care and rent costs thatexceed half of their wages. The approximately $100 per month in SNAP benefits they receive covers about one-fourth to one-fifth of their monthly food budget.[3]

-

Categorical eligibility does not cause substantial SNAP benefits to go to non-needy families. In 2011, only 2 percent of all SNAP households had monthly disposable income (i.e., income after SNAP’s deductions) above the poverty line. In other words, with the categorical eligibility option in place, virtually all SNAP households have disposable income that leaves them in poverty.

Moreover, of every $10 in SNAP benefits provided to households whose incomes are just above the federal SNAP limit but qualify for SNAP because of categorical eligibility, almost $9 goes to working households.[4]

- Categorical eligibility does not result in households being enrolled automatically. Households must still apply through the regular application process, which has rigorous procedures for documenting applicants’ income and circumstances.

- Categorical eligibility has not been a major factor in SNAP spending growth in recent years. According to CBO, states’ use of this option accounts for only about 2 percent of program costs. Factors like the severe economic downturn dwarf the effects of categorical eligibility.

- The cut would penalize families for saving modest amounts. If Congress repeals categorical eligibility, states will have to terminate benefits to poor families participating in SNAP who have managed to save as little as $2,001. Building assets helps low-income families invest in their future, avert a financial crisis that can push them deeper into poverty or even into homelessness, and have a better chance of avoiding poverty (and greater reliance on government) in old age. Research indicates that having some assets is associated with greater family stability, improved health outcomes, more economic security, and better educational results for children.

- Some working households would lose benefits merely because they own a modest car. States have used categorical eligibility to ease overly restrictive rules governing the value of a car that households may own under SNAP rules. A working family with a modest vehicle that has a market value of $5,000 to $10,000 — regardless of how little equity the household may have in the vehicle — could lose all of its SNAP benefits under the House Agriculture Committee bill. Such families often would need to choose between owning a car they may need to get to work and receiving help feeding their children.

- Some 210,000 low-income school children would lose free school lunches and breakfasts. Children in households that receive SNAP are automatically eligible for free school meals. According to CBO, 210,000 children in families whose eligibility for free school meals is tied to their receipt of SNAP would lose free school meals.

- The cut would strip states of flexibility and be administratively burdensome. Elimination of this option would make the SNAP rules that states must follow considerably more complicated, and inconsistent with the rules states use in their TANF and Medicaid programs, both of which permit states to set asset and income tests. It would thereby increase administrative costs and likely raise SNAP error rates. Eliminating categorical eligibility also would require more than 40 states to alter their SNAP eligibility rules, modify their computer systems, revise applications and program manuals, and retrain staff.

Other SNAP Cuts in the House Agriculture Committee Farm Bill

The bill includes three other significant SNAP cuts. One would eliminate SNAP incentive payments to states to improve program administration. The second, which was also included in the farm bill that the Senate approved last year (and again this week) as well as in last year’s House Agriculture Committee farm bill — but in less harsh form — would restrict states’ use of an important paperwork simplification option. A third would permanently cut funding for nutrition education for SNAP-eligible individuals.

Eliminating State Performance Funds

The bill would eliminate SNAP incentive payments to states with the best, and the most improved, SNAP performance. SNAP incentive payments, which policymakers established on a bipartisan basis in 2002, have led to reductions in error rates and overpayments and to improved service to low-income families. (Table 1 lists the bonuses that states have won since 2003.) This provision would cut SNAP spending by $480 million over ten years.

Bill Also Includes Other Harmful Provisions, As Well As Some Useful Ones

The bill places new restrictions on federal and state outreach efforts to help eligible individuals learn about and apply for SNAP. It would prohibit the use of SNAP funds for several reasonable, longstanding types of outreach activities.

States are not required to conduct outreach activities, but most do and work closely with churches, food banks, senior centers, and other community groups to connect people who need help in meeting their food needs to SNAP. The bill would prohibit outreach funds from being used for such things as developing radio public service announcements, which can be a cost-effective way to inform hard-to-reach populations about the program. The bill would also bar outreach efforts designed to help eligible individuals overcome various barriers to participation; currently, many states’ SNAP outreach efforts focus on vulnerable groups such as seniors, homeless veterans, and victims of domestic violence who are eligible for SNAP but do not participate. Members of these groups frequently have concerns about seeking government help; for example, seniors may believe their benefits leave less help for others. Providing seniors with basic information about and assistance to overcome their concerns about participating in the program is an important element of outreach. Restricting states’ use of outreach funding in these ways would likely result in some of the nation’s most vulnerable poor people going unserved and lacking adequate food.

The bill also includes several useful provisions. It would permit the Agriculture Department (USDA) and retailers to test new technologies for redeeming SNAP benefits, such as smart phones. In addition the bill provides for a pilot to test innovative federal state partnerships to combat retailer fraud. USDA also would be required to work with states to institute reporting on SNAP employment and training (E&T) program outcomes and to launch a pilot program to test innovative practices in the E&T program. In addition, non-profit grocery delivery services that assist home-bound senior or disabled SNAP participants would be able to redeem SNAP benefits for these individuals.

Leading up to the 2002 farm bill, there was bipartisan recognition that the SNAP quality control system was leading states to take actions that were intended to lower error rates but often made it more difficult for eligible low-income working families to obtain SNAP benefits. Because the system measured only how well states performed with respect to payment accuracy, it had the unintended effect of rewarding many states that made it harder for eligible working-poor families to participate in SNAP, because those states’ error rates were low compared to other states. (It is harder for states to determine SNAP benefit levels for working-poor families with precise accuracy because their incomes fluctuate depending on their hours of work, amount of overtime, loss of work due to sick days, etc.) States that endeavored to reach all eligible households, including households with fluctuating circumstances like the working poor, were more likely to have higher error rates than other states and to face fiscal sanctions as a consequence.

The states, the Bush Administration, and Congress worked together in 2002 to build a more balanced program accountability system. The system they developed remains the most rigorous of that in any federal benefit program; it includes performance measures that maintain a strong focus on program integrity and low error rates. It also measures how well states do in serving eligible households and in acting promptly when eligible households apply for assistance.

States now strive to improve both program integrity and overall SNAP operations. Performance bonuses are available to the top and the most improved state performers across four measures. All states have an incentive to improve performance with respect to these measures, which has produced highly beneficial results.

- Error rates have declined markedly. Since the incentive payments were put in place, the SNAP error rate (the sum of the program’s overpayment and underpayment rates) has dropped from 6.6 percent in 2003 to 3.8 percent in 2011 — a reduction in payment errors of nearly 43 percent. Had the overpayment rate in 2011 been at the 2003 level, the increased loss to the federal government would have been $1.5 billion. The saving the federal government has secured as a result of this reduction in errors dwarfs the cost of the $48 million in annual performance incentive payments.

- Access to SNAP by eligible households also has improved. The Program Access Index (a measure of the percentage of eligible people who participate in SNAP) rose from 62 percent in 2003 to 72 percent in 2011. Policymakers should not allow SNAP to slide backward in this area; a reduction in access to SNAP among eligible households would increase hardship. It would also lead to an increase in demand at already overburdened food banks and local charities.

States often use these incentive funds to reinvest in their SNAP programs to make further improvements. States have used these funds to help finance online application systems, eligibility worker training and other eligibility worker tools to increase efficiency and further lower error rates, improved data matching to verify household earnings, and job training for unemployed SNAP recipients. A number of states have also provided a share of the incentive funding to food banks to help them meet the needs placed upon them.

Restricting Standard Utility Allowance (SUA) Simplification

The bill would restrict states’ ability to use an important program simplification that reduces paperwork in determining household benefit levels. Based on CBO estimates, the provision would reduce benefits for about 850,000 households, which include about 1.7 million people, primarily in 15 states, by an average of about $90 a month — producing a $8.7 billion benefit reduction over ten years. (Table 1 lists the 15 states.) The households affected by the cut would disproportionately be low-income seniors, people with disabilities, and working-poor families with children.

SNAP benefits are targeted to households based on their ability to purchase adequate food. When calculating the income that a household has available for food, SNAP provides deductions for certain essential household expenses. One of the most important deductions, the shelter deduction, is available to households that expend more than half of their disposable income on housing and utility expenses. (Only the housing and utility expense amount in excess of 50 percent of a household’s disposable income is deducted.) The deduction ensures that households that face very high housing and utility costs in relation to their income — for example, because they receive no federal or state housing assistance or live in a colder climate — receive sufficient SNAP benefits to purchase a bare-bones, nutritionally adequate diet.

States can simplify the shelter deduction by establishing Standard Utility Allowances (SUAs) that reflect typical low-income households’ utility bills in the state, rather than requiring every household to provide copies of its monthly utility bills and requiring caseworkers to try to calculate each household’s average month utility costs. Households that can demonstrate they have out-of-pocket utility costs for heating and cooling costs are assigned an SUA that reflects those costs, in lieu of calculating each household’s utility expenses.

Federal law has long considered a household’s receipt of assistance from the Low-Income House Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) a sound test of whether the household incurs utility expenses and hence qualifies for the SUA. LIHEAP is targeted to low-income households that cannot afford to pay their home energy bills, although it defrays only a fraction of such households’ utility expenses. For decades, SNAP households that receive LIHEAP have been eligible for the SUA, based on LIHEAP’s determination that the household has home energy bills that it needs assistance in meeting.

This connection between the two programs reduces unnecessary paperwork for eligible households and state SNAP agencies. Without this streamlined approach, many more households would have to provide SNAP caseworkers with enough of their utility bills to document that they incur costs for heating or cooling their homes.

In recent years, however, some states have gone further and have provided a nominal LIHEAP benefit of $1 to $5 to SNAP households in order to qualify those households for an SUA and the larger SNAP shelter deduction that results. This has allowed some low-income households that pay utilities through their rents, rather than directly, to deduct more in excess shelter costs than is warranted and to receive higher SNAP benefits.

Some states have also used the provision of modest LIHEAP payments for another, sounder purpose. LIHEAP funds are limited and, in many states, LIHEAP serves only a fraction of the low-income households who qualify for it. With rising SNAP caseloads and fewer administrative resources, some states have used the provision of small LIHEAP payments as a means of ensuring that low-income households that do incur heating or cooling costs are able to claim those costs while reducing paperwork burdens for their SNAP workers (and hence the number of staff they need to conduct SNAP eligibility determinations). For example, if a household applies for LIHEAP in December, the states may already have distributed almost all of its annual LIHEAP funds. Having to document expected heating bills in the upcoming winter in advance of actually incurring the cost, could be difficult for the household. So the states may wish to ensure that the household has access to the SNAP SUA in order to help offset the high cost of heating its home during the coming winter months. A modest LIHEAP payment could ensure the household receives the SUA.

The farm bills that the Senate and the House Agriculture Committee passed last year (and the farm bill passed by Senate Agriculture Committee this week), took a targeted approach to addressing this issue. This year’s House Agriculture Committee bill, in contrast, takes a blunter approach and goes further than is needed to curb the practice in some states of providing nominal LIHEAP payments to some households that don’t actually incur out-of-pocket heating or cooling costs. In doing so, it doubles the cut in this area relative to last year’s bills.

About 850,000 low-income households, which include about 1.7 million individuals, would lose an average of $90 a month in SNAP benefits as a result of the House Agriculture Committee bill. This year’s bill includes a substantially larger, less-well-targeted cut in this area apparently in order to increase the size of the bill’s SNAP cuts. According to CBO, twice as many low-income households would face a benefit loss under this provision as under the more targeted version of this provision in the Senate bill and in last year’s bills. These additional cuts could result in hardship, particularly for elderly and disabled individuals who benefit disproportionately from the simplification in many of the affected states.

Cutting Funding for Nutrition Education

The bill would also impose a permanent reduction in funding for SNAP’s nutrition education program (SNAP-Ed) which promotes healthy eating choices to SNAP eligible low-income people on a tight budget. Under the bill, SNAP-Ed’s fiscal year 2014 funding would be reduced by $26 million, from $401 million to $375 million, and adjusted each year thereafter for inflation, resulting in a ten-year cut of $274 million. This proposed cut comes on the heels of the program’s fiscal year 2013 budget cut of 28 percent that was included in the fiscal cliff agreement, resulting in decreased program activity. SNAP-Ed is the only nutrition education program in SNAP that helps families choose healthy foods on a very tight budget. With an average of $1.50 per person to spend on each meal, SNAP participants face difficult economic choices at the grocery store, where less nutritious food is often cheaper than healthier options. SNAP-Ed works to improve low-income individuals’ knowledge and skills related to making healthy food choices, stretching food budgets, and preparing nutritious meals. Cutting these funds compromises states’ ability to run comprehensive programs.

Smaller Provisions That Would Also Impact Costs

The bill also includes a handful of much smaller provisions that cut program spending as well as others that provide for new spending. It includes a provision to require retailers to pay for the cost of equipping their stores with the terminals that accept SNAP debit cards and an additional $5 million per year in funding for USDA to strengthen retailer and recipient program integrity.

The bill would provide $217 million in increased funding for food banks over the next ten years through The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) and $100 million over ten years in additional funding for Community Food Projects. It would provide a total of $30 million to test and evaluate innovative state practices with respect to SNAP’s employment and training program. Finally, the bill includes $33 million for a pilot to test extending SNAP program rules to the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (in lieu of its current alternative SNAP program.)

Rationale for Cuts Reflects Inaccurate Claims Regarding SNAP Growth

Some policymakers, including some House Agriculture Committee members who have pushed for the SNAP cuts in the bill, have justified such cuts primarily by claiming that the program is growing out of control. Such charges are mistaken: SNAP costs have indeed grown substantially over the past decade, but for reasons that show the program is working, and they are expected to fall substantially in the years ahead as the economy recovers.

As CBO recently stated, “the primary reason for the increase in the number of SNAP participants was the deep recession from December 2007 to June 2009 and the subsequent slow recovery; there were no significant legislative expansions of eligibility for the program during that time.”[5] The recession dramatically increased the number of low-income households that qualify and have applied for help from the program; SNAP expanded to meet the increased need. Without SNAP, poverty and hardship would have been significantly greater in the last few years.

To be sure, the economic downturn does not explain allof the recent increase in SNAP costs. Some people assume that eligibility expansions are largely responsible for the remainder of the cost increase and that, as a result, SNAP expenditures and participation will continue growing even after the economy recovers. Such assumptions are not correct.

Aggravating this problem, some states instituted administrative practices in those years that had the unintended effect of making it harder for many working-poor parents to participate in SNAP (largely by forcing them to take too much time off from work for repeated visits to SNAP offices at frequent intervals, such as every 90 days, to reapply for benefits).

This prompted many to call for reforms that would improve access to SNAP for low-income working families and led both the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations to act to address this problem. A bipartisan consensus emerged that making it difficult for families to continue receiving SNAP when they left welfare for low-wage work would discourage work and conflict with welfare reform goals.

As a result, Congress enacted meaningful, though relatively modest, changes in 2002 and 2008 to lessen barriers to SNAP participation among the working poor, as well as modest improvements in benefits largely aimed at low-wage workers and their families. In addition, most states took steps to improve access for low-income working families. These measures have succeeded: the SNAP participation rate, which had plummeted from 75 percent of eligible individuals receiving SNAP assistance in 1994 to 54 percent in 2002, is back to 75 percent today.[6] Of particular note, SNAP participation among low-income working families has risen from 43 percent in 2002 to about 65 percent in 2010, a record high.

The final major contributor to recent SNAP spending growth is the temporary SNAP benefit increase that Congress enacted as part of the 2009 Recovery Act in order to reduce hardship and deliver high “bang-for-the-buck” economic stimulus. CBO reports that this provision accounted for 20 percent of the growth in program cost between 2007 and 2011.[7] The temporary benefit increase is now phasing down and terminates entirely at the end of October 2013.

In sum, there are threemain reasons for the large increase over the past decade in SNAP expenditures: the economy; a substantial increase in participation among eligible households, especially eligible working households; and the Recovery Act’s temporary benefit increase.

What lies ahead for SNAP costs? Under current SNAP law, without any changes, expenditures will decline in the coming years, for two reasons.

First, history demonstrates that SNAP caseloads and expenditures fall after unemployment and poverty fall, as CBO’s recent report on SNAP notes. The poverty rate has not yet begun to decline, but should begin to do so as the economy more fully recovers. SNAP caseload growth has slowed dramatically in the past year, and CBO projects that in the years ahead, the share of the population participating in SNAP will drop and fall back to its 2008 level.

In addition, as noted, the Recovery Act benefit increase is slated to end on October 31, 2013, reducing benefits for all SNAP households. The benefit reduction all participants will face when the Recovery Act’s benefit increase ends will be significant — for the average household of three, the benefit loss will be $20 to $25 a month. When the Recovery Act’s benefit increase expires, average SNAP benefits will fall to about $1.40 per person per meal.

Figure 1 shows where this will lead. CBO expects SNAP costs as a share of the economy to decline back to their 1995 level by 2019, and then to edge below that level.

This means that SNAP is notcontributing to our long-term budgetary problems. Unlike health care programs and Social Security, there are no significant demographic or programmatic pressures that will cause SNAP costs to grow faster than the economy in the years and decades ahead. This also means that the recent growth in SNAP expenditures is not a sound justification for imposing substantial SNAP cuts on needy households.

| Table 1 State-by-State Impact of the House Agriculture Committee’s Proposed SNAP Cuts | ||||

| State/Territory | Has the State Adopted the Expanded Categorical Eligibility Option* | Affected by House Standard Utility Allowance Change | Number of Performance Bonuses Since 2003** | |

| Asset Test | Income Test | |||

| Alabama | Yes | 2 | ||

| Alaska | 6 | |||

| Arizona | Yes | Yes | 1 | |

| Arkansas | 2 | |||

| California | Yes | Yes | 1 | |

| Colorado | Yes | 3 | ||

| Connecticut | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 |

| Delaware | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| District of Columbia | Yes | Yes | Yes | 14 |

| Florida | Yes | Yes | 7 | |

| Georgia | Yes | 4 | ||

| Guam | Yes | Yes | 1 | |

| Hawaii | Yes | Yes | 4 | |

| Idaho | Yes | 7 | ||

| Illinois | Yes | 3 | ||

| Indiana | 1 | |||

| Iowa | Yes | Yes | 2 | |

| Kansas | 4 | |||

| Kentucky | Yes | 7 | ||

| Louisiana | Yes | 4 | ||

| Maine | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 |

| Maryland | Yes | Yes | 2 | |

| Massachusetts | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 |

| Michigan | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| Minnesota | Yes | Yes | 4 | |

| Mississippi | Yes | 6 | ||

| Missouri | 10 | |||

| Montana | Yes | Yes | 5 | |

| Nebraska | Yes | 11 | ||

| Nevada | Yes | Yes | 1 | |

| New Hampshire | Yes | Yes | 9 | |

| New Jersey | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| New Mexico | Yes | Yes | 3 | |

| New York | Yes | Yes | 3 | |

| North Carolina | Yes | Yes | 9 | |

| North Dakota | Yes | Yes | 5 | |

| Ohio | Yes | 2 | ||

| Oklahoma | Yes | 5 | ||

| Oregon | Yes | Yes | Yes | 11 |

| Pennsylvania | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| Rhode Island | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| South Carolina | Yes | 4 | ||

| South Dakota | 21 | |||

| Tennessee | 6 | |||

| Texas | Yes | Yes | 3 | |

| Utah | 1 | |||

| Vermont | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Virginia | 2 | |||

| Virgin Islands | Yes | 5 | ||

| Washington | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| West Virginia | Yes | 9 | ||

| Wisconsin | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Wyoming | 3 | |||

| United States | 43 | 27 | 15 | |

| * These states have adopted broad-based categorical eligibility. Additional states have narrow categorical eligibility (beyond cash assistance, but not affecting large numbers of households) and may also have some households that would be cut off SNAP. ** States may win more than one performance bonus in a year. Sources: USDA, Food and Nutrition Service, Broad-based Categorical Eligibility Chart, performance bonuses by year, and private correspondence. See http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/rules/Memo/BBCE.pdf and http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/government/program-improvement.htm. | ||||

End Notes

[1] The legislation, as amended, likely will be available at: http://agriculture.house.gov/farmbill.

[2] The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) cost estimate of the bill as proposed prior to the mark-up is available at: http://www.cbo.gov/publication/44177?utm_source=feedblitz&utm_medium=FeedBlitzEmail&utm_content=812526&utm_campaign=0. No major amendments affecting SNAP costs were adopted during the Committee’s May 15th nutrition title deliberations. We are not aware of changes in other titles that would affect the bill’s total cost estimate. A final CBO cost estimate will be included in the Committee report. The SNAP cuts of $20.5 billion are the net cuts after modest investments in funding for food banks, community food security grants, and a few other areas are considered. The total farm bill savings of $39.7 billion include the effects of sequestration on mandatory agricultural programs.

[3] Based on CBPP analysis of SNAP quality control administrative data for 2011 regarding households whose incomes exceed the federal SNAP limit but qualify for SNAP because of categorical eligibility. The analysis excludes the effects of the 2009 Recovery Act’s SNAP benefit increase because that increase will already have expired during all but one month of the 2014-2023 budget period.

[4] See previous footnote.

[5] Congressional Budget Office, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” April 2012.

[6] The most recent year for which USDA publishes estimates is 2010.

[7] CBO, op. cit.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise