The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program’s (SNAP) primary purpose is to increase the food purchasing power of eligible low-income households in order to improve their nutrition and alleviate hunger and malnutrition.[1] The program’s success in meeting this core goal has been well documented.[2] Less well understood is the fact that the program has become quite effective in supporting work and that its performance in this area has improved substantially in recent years.

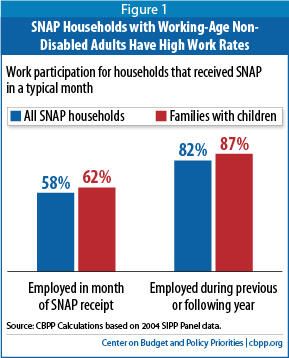

The overwhelming majority of SNAP recipients who can work do so. Among SNAP households with at least one working-age, non-disabled adult, more than half work while receiving SNAP — and more than 80 percent work in the year prior to or the year after receiving SNAP. The rates are even higher for families with children — more than 60 percent work while receiving SNAP, and almost 90 percent work in the prior or subsequent year. (See Figure 1.)

[3]

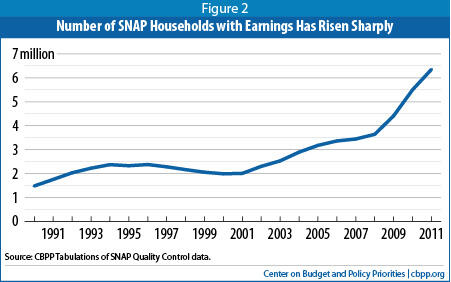

The number of SNAP households that have earnings while participating in SNAP has been rising for more than a decade, and has more than tripled — from about 2 million in 2000 to about 6.4 million in 2011. (See Figure 2.) The increase was especially pronounced during the recent deep recession, suggesting that many people have turned to SNAP because of under-employment — for example, when one wage-earner in a two-parent family lost a job, when a worker’s hours were cut, or when a worker turned to a lower-paying job after being laid off.

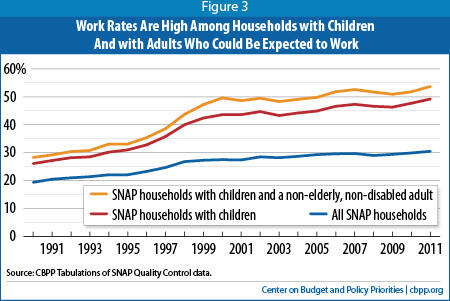

The large increase in the number of working SNAP households in recent years has resulted in the share of SNAP households that are working rising, even as the overall number of Americans who are employed declined and the number of long-term unemployed swelled. (See Figure 3.)

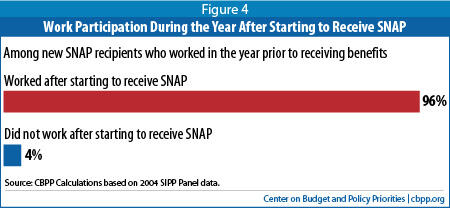

The data also indicate that SNAP receipt does not create work disincentives. The overwhelming majority of non-disabled, working-age households that start receiving SNAP do not stop working. In the mid-2000s, only 4 percent of SNAP households that worked in the year before starting to receive SNAP did not work in the following year.[4] (See Figure 4.)

The high labor force participation rate among SNAP recipients is not accidental — SNAP is designed to act both as a safety net for people who are elderly, disabled, or temporarily unemployed and to supplement the wages of low-income workers.

- SNAP’s basic structure supports work. Households that meet the program’s eligibility rules and requirements can qualify for benefits and be served if they apply. As a result, SNAP is able both to respond quickly and effectively in recessions and to act as a longer-term support for low-wage workers. SNAP typically boosts low-wage workers’ income by 10 percent or more.

- The SNAP benefit formula includes work incentives. SNAP targets benefits based on a household’s income and expenses, including a deduction for earned income to reflect the cost of work-related expenses and to function as a work incentive. As a result of the SNAP benefit calculation rules, SNAP households are financially better off if they are able to secure employment or increase their earnings.

- SNAP cushions the effects of weaknesses in the labor market. SNAP plays important roles in helping workers who lose their jobs during recessions as well as in supporting low-income workers who are impacted by broader adverse trends in the low-wage labor market. SNAP was the most responsive of all means-tested benefit programs during the recent deep recession and ensuing weak recovery. It also helps workers who struggle to make ends meet when they cannot find higher paying jobs or jobs with sufficient hours.

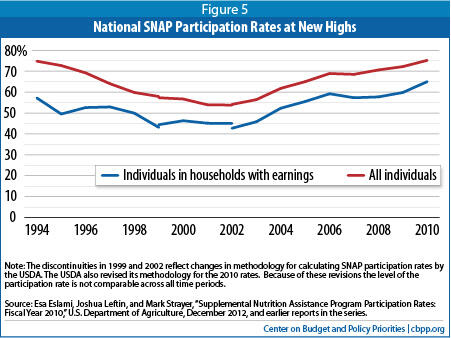

SNAP’s performance in reaching eligible working households has improved over the past decade as a result of bipartisan efforts at the federal, state, and local levels to respond to previous weaknesses in this area. The efforts have paid off, with estimated participation rates (i.e., the portion of eligible households that actually receives benefits) hitting highs in recent years; the SNAP participation rate among eligible low-income working families, which fell after enactment of the 1996 welfare law (although that was not what the authors of the law intended), rose from 43 percent in 2002 to about 65 percent in 2010. (See Figure 5.)