As state legislative sessions move forward, policymakers can help build an economy that works for everyone by adopting or strengthening two policy tools at their disposal: state earned income tax credits (EITCs) and state minimum wages. These are the twin pillars of making work pay for families that earn low wages. They boost income, widen the path to the middle class, and help make sure that the benefits of economic growth are more widely shared. They also help women and communities of color — two groups that disproportionately work in low-wage jobs — see more of the fruits of their labor and share more fully in the benefits of economic growth. And they help build a stronger future by putting children on a better path in life. The increased income helps working parents better meet the needs of their children, and as a result, research has found, those children do better in school and earn more in adulthood.[1]

Strengthening either a state’s minimum wage or a state EITC will boost incomes for low-wage working families, but these improvements are particularly effective in combination:

- State minimum wages and EITCs reach overlapping but different populations. Each supports some families and individuals that the other doesn’t reach. For example, EITCs primarily target low-income families with children and are available to working families earning up to more than three and a half times a full-time minimum wage worker’s annual salary of $14,500. The minimum wage targets the very lowest-wage workers regardless of factors like total family income, family status, or age.

- Increasing both at the same time provides added support to the working families who need it most. Together, a minimum wage boost and a robust state EITC can move families beyond poverty and further along the road to economic security. A minimum wage increase provides the added benefit of increasing the EITC for some families.

- Workers receive the benefits of the two policies on different schedules. An expanded minimum wage increases every paycheck, which helps workers cover routine expenses like food, monthly bills, and rent. State EITCs are paid at tax time and can be used for larger, one-time expenses, like car repairs or a security deposit.

- A combination allows the public and private sectors to share the cost of boosting workers’ incomes. The EITC’s cost is largely borne by state governments and the revenue they collect. The state minimum wage is borne principally by the private sector, especially employers and consumers. Improving both policies spreads the cost of increasing incomes for people earning the lowest wages more broadly than does either policy alone.

Recent improvements to the federal EITC and the federal Child Tax Credit, as well as past increases in the federal minimum wage, have helped many working families with low incomes across the country move closer to or above the poverty line. But we need to do more to get working families and individuals on a path to financial stability and opportunity. State lawmakers can use their own policy tools to help keep people working, increase incomes, and reduce financial hardship.

Many states have raised their minimum wage in the past several years, and states continue to strengthen their EITCs. New Mexico expanded both in 2019, Massachusetts did so in 2018, Oregon did so in 2016, and Rhode Island did so in 2015.[2] In 2014, three states — Maryland, Minnesota, and Rhode Island — plus the District of Columbia strengthened both. Other states also should look to advance the two policies in tandem for the biggest impact. Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, New Mexico, and Nevada approved minimum wage increases in 2019,[3] and the minimum wage will rise in 24 states in 2020.[4] In addition, last year six states — California, Maine, Minnesota, New Mexico, Ohio, and Oregon — expanded their EITCs, and Maine also expanded access to the EITC for workers without dependent children in the home.

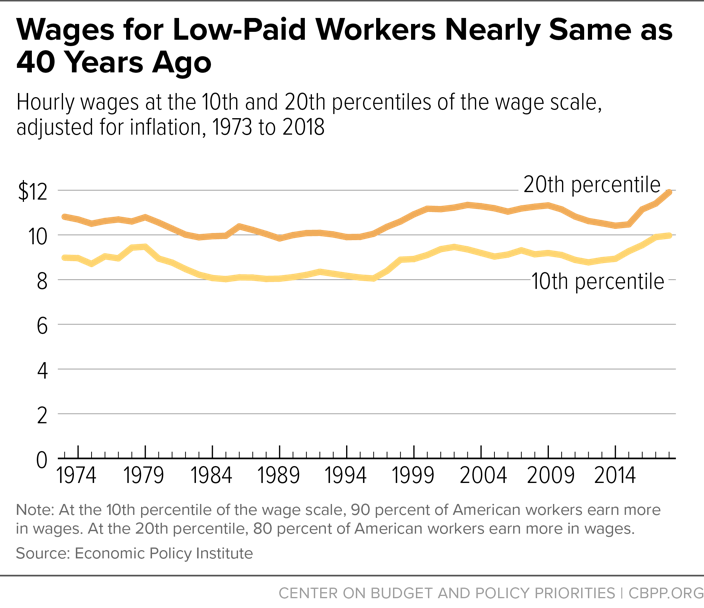

Low wages make it hard for families to afford basics like decent housing in safe neighborhoods, nutritious food, reliable transportation, and quality child care, as well as educational opportunities that can move them toward the middle class. But the wages of workers paid the least are not much higher than they were over 40 years ago, after adjusting for inflation.

For the most part, wages for lower-paid workers have stagnated or declined over this period, with the only period of sustained growth coming from the late 1990s to the early 2000s;[5] the wage growth of the past few years remains weak compared to the late 1990s.[6] Wages fell during the Great Recession and didn’t tick back up again until 2014 and 2015. In 2018, the 20th percentile wage (that is, the wage that exceeds the bottom 20 percent of wages) was 10.2 percent higher than in 1973 and 6.5 percent higher than in 2007, after adjusting for inflation. The 10th percentile wage was 11 percent higher than in 1973 and 7.1 percent higher than 2007, likely due to the state minimum wage increases of the past few years. (See Figure 1.) To put those gains into context, wages at the bottom have barely budged when compared with significant productivity growth over that same time period (productivity has increased 70 percent since 1979, or 6 times more than pay).[7] In other words, many workers are not sharing in the benefits of economic growth.

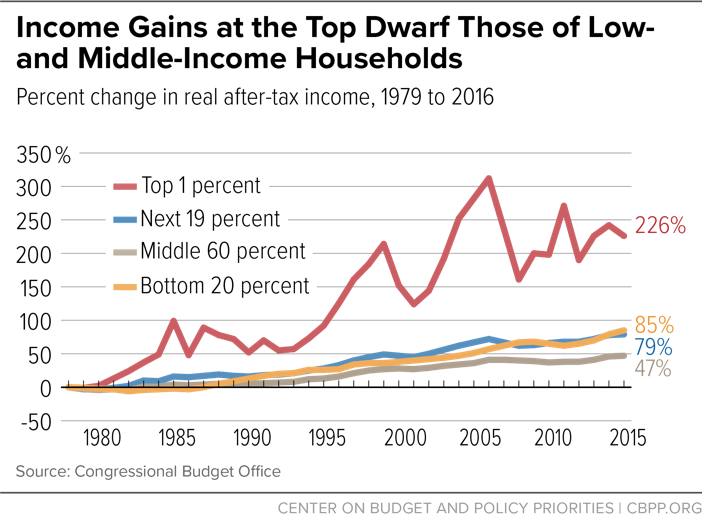

Instead, those benefits have been concentrated high on the income spectrum. Looking at income from all sources, after taxes and adjusted for inflation, the richest 1 percent of households have seen extraordinary income growth since 1979, peaking at a 312 percent increase in 2007. The Great Recession substantially reduced these gains, but incomes still grew almost three times faster for the top 1 percent of households than for the poorest households between 1979 and 2016. (See Figure 2.)

This glaring disparity has major consequences. The share of income going to the poorest one-fifth of households fell from 4.1 percent in 1979 to slightly over 3 percent in 2018, according to Census Bureau data. If inequality hadn’t grown — that is, if incomes had grown at the same rate for all income groups over this period — incomes for the bottom quintile would have been 24 percent higher in 2018 than they actually were. And if all poor people’s incomes rose 24 percent faster, the number of people below the official poverty line in 2018 would have been 8.9 million lower, our analysis of the Current Population Survey shows. The disparity in income growth has had a much bigger impact on the poverty rate than other commonly cited factors like demographic changes and increases in the number of families headed by single mothers, according to an Economic Policy Institute (EPI) analysis.[8]

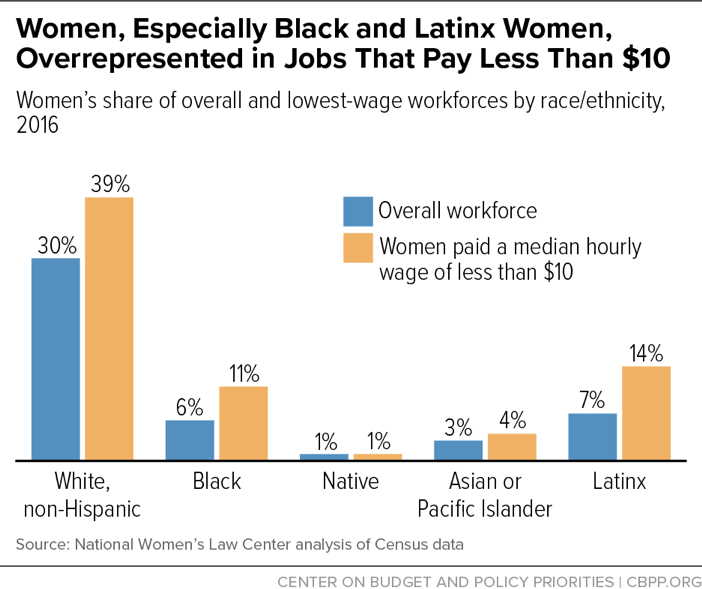

The failure of economic growth to reach low-wage workers to a greater degree particularly affects women and people of color. Women, for example, comprise less than half of the total workforce, but in every state except Nevada they represent roughly 3 in 5 workers in occupations with low pay.[9] Black and Latinx women comprise about twice as big a share of the low-wage workforce as they do of the workforce as a whole (see Figure 3).[10] And Black and Latinx workers in general are far more likely than white workers to earn poverty-level wages.[11]

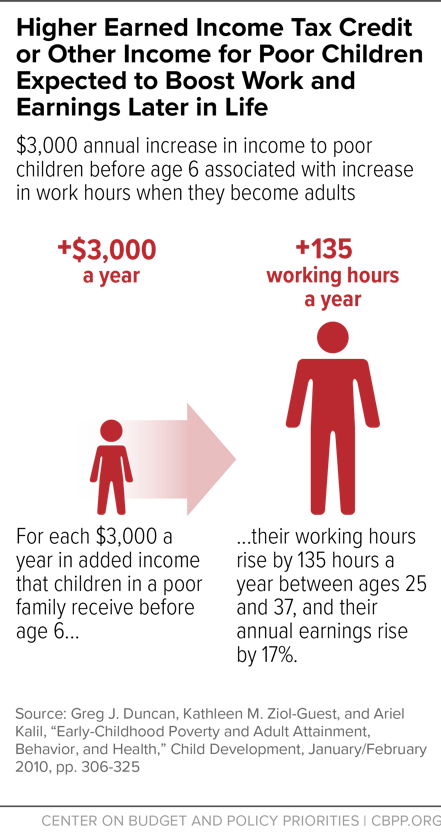

Persistent inequality and barriers to higher-paying jobs for women and people of color also have inter-generational implications. The effects of low pay and poverty can last a lifetime for children. Relative to their better-off peers, poor children do less well in school, complete fewer years of education, and work less (and earn less) as adults. One reason appears to be that poor children are more likely to be in poor health, which can affect their ability to learn and sometimes carries into adulthood.[12] Another reason is the stress associated with poverty. Unsafe neighborhoods, unstable housing, hunger, and other hardships associated with poverty can affect children’s still-developing brains, impeding their social and emotional development and ability to learn.[13]

State policymakers can partially address stagnant wages, hardship, and extreme income inequality by enacting or expanding a state EITC and by raising their state’s minimum wage and then maintaining its real value over time by indexing it to inflation. Both policies would buoy workers and their families and help them meet basic needs. These policies can also support local businesses and economies, since low- and moderate-income households spend (rather than save) most of what they earn to cover living costs.

Enacting or Expanding State EITCs

Federal and state EITCs go to low-income working families and individuals. Together with the federal credit, state EITCs:

- Help working families make ends meet. Many low-wage jobs fail to provide enough income on which to live. “Refundable” EITCs, which give working households the full value of the credit they earn even if it exceeds what they owe in income taxes, provide workers struggling on low wages with a needed income boost that can help them meet basic needs.

- Keep families working. Refundable EITCs help working families paid low wages afford the very things that allow them to continue working, like child care and transportation. Research demonstrates that unmarried mothers, in particular, work more hours as a result of the credit. That extra time and experience on the job can translate into better opportunities and higher pay over time.[14] Three in five filers who receive the federal credit use it temporarily — for just one or two years at a time.[15]

- Reduce poverty, especially among children. Eight million children in working families lived below the official poverty line (about $25,500 for a family of four) in 2018;[16] millions of families modestly above that income level have difficulty affording food, housing, and other necessities. The federal EITC is one of the nation’s most effective tools for reducing the struggles of working families and children, particularly for unmarried women with children. It kept 5.6 million people — over half of them children — out of poverty in 2018, and helped many with somewhat higher incomes make ends meet. And by boosting the employment of working-age parents, particularly women, the EITC also increases their Social Security retirement benefits and thereby reduces poverty among seniors.[17] State EITCs build on that record.

- Have a lasting effect. A growing body of research finds that young children in low-income families that get an income boost like the EITC provides tend to do better and go further in school because the additional resources help parents better meet their needs. (See Figure 4.) Research suggests that boys and children of color particularly benefit.[18] Children growing up poor tend to work less and earn less as adults relative to better-off peers; conversely, children receiving additional income such as from the EITC are likelier to see their employment and earnings prospects improve.[19] This helps communities and the economy because it means more people and families are on solid ground over the long haul.

State EITCs also help to address skewed state tax systems that require low- and moderate-income families to pay a larger share of their income in taxes than high-income families. On average across the country, the lowest-earning households (those with incomes less than $20,800) pay about 11 percent of their income in state and local taxes, while the top 1 percent pay just 7 percent, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.[20] Refundable credits targeted toward people struggling on low incomes, including EITCs, can help address this imbalance.

Twenty-nine states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico have EITCs. (See Table 1.)

- In 2019, six states — California, Maine, Minnesota, New Mexico, Ohio, and Oregon — expanded the size of their credits, and Maine also expanded access to the EITC to younger workers without dependent children.

- In 2018, Puerto Rico created a new credit, Louisiana, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Vermont all increased the size of their credits, and California and Maryland expanded access to the credit for some people who were previously ineligible.

- In 2017, Montana, Hawaii, and South Carolina created new credits, and California, Illinois, and Minnesota substantially expanded theirs.

- In 2016, New Jersey, Oregon, and Rhode Island expanded the size of their credits.

Increasing State Minimum Wages and Indexing Them for Inflation

Like the EITC, higher minimum wages can boost income and set children on a better path in life. They also allow working households to purchase more things their families need, like child care and transportation, and these added purchases in turn help boost state and local economies.

The federal minimum wage is the nation’s wage floor. A number of states set their minimum wage above the federal minimum wage. Other states set their minimum wage at the federal minimum wage, or have a lower state minimum wage or no minimum wage at all, in which case the federal minimum wage becomes the default for most workers.[21]

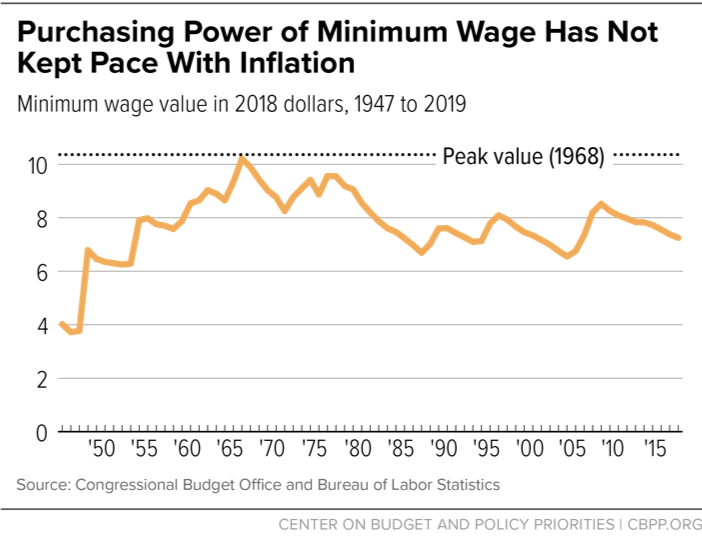

Yet the federal minimum wage hasn’t kept pace with the cost of living. It is currently 29 percent below its peak value in 1968, after adjusting for inflation. (See Figure 5.) Today, a full-time worker earning the federal minimum wage and supporting two children lives below the poverty line.

Raising the minimum wage would greatly improve the outlook for the nation’s lowest-wage workers, especially those in sectors of the economy that have seen little to no wage growth. A 2019 proposal to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 by 2025 and index it to the nation’s median wage, and to bring the tipped worker wage ($2.13 per hour) into line with the standard minimum wage, would boost wages directly for 23.2 million workers, according to the EPI. Among the workers who would be affected, the vast majority are adults, most are without a college degree, and over half are women. Over half also work full-time. More than half affected are white, but almost one-third of all African American workers and over a quarter of all Latinx workers would benefit, compared with one-fifth of white workers. The raise would be enough to keep a family of four with one minimum-wage earner above the poverty line.[22] Many of the workers receiving a wage boost from the proposed increase — an estimated 10.2 million of them in 2025 — would be workers earning slightly more than the proposed $15 per hour, since employers typically increase the wages of workers slightly above the new minimum.

States shouldn’t wait for the federal government to raise the minimum wage when they can improve the lives of their state’s workers now. Many have done just that.

- In 2019, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Nevada, New Jersey, and New Mexico increased their minimum wages, with legislative approval.

- In 2018, Arkansas and Missouri increased their minimum wage via ballot initiative, and Delaware and Massachusetts did so via legislative approval.

- In 2017, Rhode Island increased its minimum wage by legislation.

- In 2016, Arizona, Colorado, Maine, and Washington increased their minimum wages via ballot initiative, and California and Oregon did so via legislative approval.

In addition, major cities like Los Angeles, New York City, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, D.C., have increased their minimum wages to $15 per hour, as have smaller cities like San Jose, California; SeaTac, Washington; and Flagstaff, Arizona. Many other cities have adopted smaller increases in the last couple of years.[23] In addition, 19 states have adopted cost-of-living adjustments to their minimum wages — 15 of them since 2014 — that help workers keep up with expenses. In total, 21 states raised their minimum wage in 2019, through a combination of newly or previously approved increases and cost-of-living adjustments.[24]

As of December 2019, 29 states and the District of Columbia have a minimum wage higher than the federal wage, although 11 of them don’t index it to inflation. These 11 states ― Arkansas, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Nebraska, New Mexico, Rhode Island, and West Virginia ― should take that additional step to ensure that their minimum wage keeps pace with the cost of living. In addition, the 21 states plus Puerto Rico that have no minimum wage or have set their minimum wages at or below the federal minimum should improve their minimum wage to help working families meet basic needs and have more opportunity to get ahead.

State EITC and Minimum Wage Improvements Go Hand in Hand

New Mexico expanded both its state EITC and its minimum wage in 2019. Massachusetts did so in 2018; Oregon did so in 2016; Rhode Island did so in 2015 and 2014; and the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Minnesota did so in 2014. While improving either policy helps low-wage workers, improving both in combination produces complementary benefits and goes much further to make work pay.

-

State minimum wages and EITCs reach overlapping but different populations. The EITC and minimum wage are targeted differently, so enacting or improving both policies in tandem will reach more workers than either on its own. For example, the EITC targets low-income working families with children. Single workers without children working full-time, year-round at the minimum wage are eligible for a federal EITC worth only about $80 and are ineligible for the credit if they are younger than 25 or older than 64. Higher minimum wages, in contrast, benefit low-wage workers regardless of age, presence of children in the household, or total family income.

Similarly, while the minimum wage is focused on workers with the very lowest wages, the EITC remains available (albeit at gradually declining levels) to families as their income rises. (Of course, some minimum wage workers are also in families with higher incomes.) In addition, the EITC reaches some workers not covered by minimum wage laws, such as domestic workers and farm workers. And the EITC provides an additional boost to families with more than one child, which the minimum wage cannot do.

-

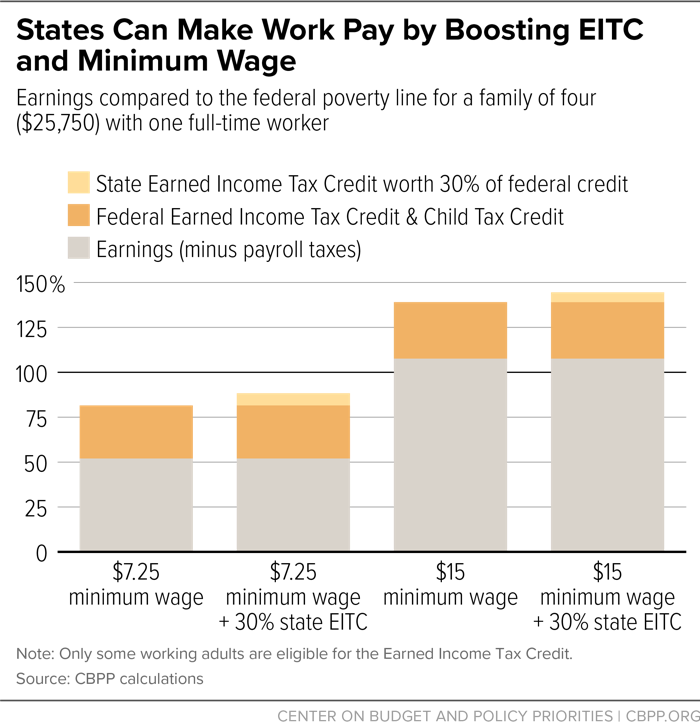

Increasing both at the same time provides added support to the working families who need it most. Families modestly above the poverty line often can’t meet basic needs. Improving state EITCs and minimum wages together not only helps more families climb out of poverty, but also helps working families get further down the road to economic security. [25]

For example, a two-parent, two-child family with one full-time, year-round minimum wage worker claiming the federal EITC and Child Tax Credit has after-tax income of $21,001, which is below the poverty line ($25,750 for a family of four in 2019). Adding in a state EITC set at 30 percent of the federal credit helps significantly but still leaves this family at 88 percent of the poverty line. But boosting the family’s hourly wage to $15 through a minimum-wage increase would raise its income to 139 percent of the poverty line. And a working family that benefits from both policies takes an even bigger step forward, seeing its income rise by close to one-third, to 145 percent of the poverty line. (See Figure 6.)

In addition, for many families with very low earnings, a higher state minimum wage boosts their federal and state EITCs, which rise with every additional dollar earned until reaching the maximum credit.[26] For example, even a small minimum wage increase from $7.25 to $7.75 for a single mother with two children working 35 hours per week would raise her federal EITC by $360.

The more each policy overlaps with one another, the more effective they are together. Moreover, a higher minimum wage can protect workers receiving EITCs from downward pressure on wages, and higher EITCs for workers receiving minimum wages boost their incomes more than wages can do alone.[27]

- Workers receive the benefits of the two policies on different schedules. The EITC offers an annual, lump-sum payment when a family files income taxes. This payment helps many families afford major expenses like car repairs or a security deposit that facilitates a move to a better neighborhood, or it can provide them with funds to build a savings account.[28] An increase to the minimum wage, on the other hand, provides a boost year-round with every paycheck, helping working families afford monthly expenses like rent, utilities, and child care.

- A combination approach allows the public and private sectors to share the cost of boosting workers’ incomes. Strengthening both the EITC and the minimum wage in the same general timeframe ensures that both government and the private sector are working together to boost wages for people earning the least. The cost of state EITCs is largely borne by state government, and by extension state tax revenues, while the cost of a state minimum wage is borne primarily by the private sector, especially employers and consumers.[29] (Where costs ultimately fall is not as straightforward as it might seem, given the interplay of the two policies and other programs for low-income workers. For example, a minimum wage increase will boost some workers’ federal and state EITCs, thereby raising the cost of providing a state EITC but also adding EITC dollars into workers’ pockets and the state economy, which in turn raises state tax collections.)

A higher state EITC and a higher state minimum wage individually offer significant support to many low-income workers. States are right to consider strengthening these policies, which help make work pay and help struggling families make ends meet. But a strong state EITC and an increased minimum wage are even more powerful, and support more working people, when they are combined.

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 |

|---|

| State EITCs and Minimum Wages |

|---|

| State |

EITC as Share of

Federal EITC (2019) |

Minimum Wage (As of January 1, 2020) |

Minimum Wage

Indexed to Inflation? |

|---|

| Alabama |

None |

Noneb |

No |

| Alaska |

None |

$10.19 |

Yes |

| Arizona |

None |

$12.00 |

As of Jan. 2021 |

| Arkansas |

None |

$10.00 a |

No |

| California |

85% up to 50% of federal

phase-in range]c |

$13.00a |

As of Jan. 2023 |

| Colorado |

10% |

$12.00 |

As of Jan. 2021 |

| Connecticut |

23% |

$11.00 a |

As of Jan. 2024 |

| Delaware |

20% (non-refundable) |

$9.25 |

No |

| District of Columbia |

40%

100% (workers not raising children)d |

$14.00a |

As of Jul. 2021 |

| Florida |

None |

$8.56 |

Yes |

| Georgia |

None |

$5.15b |

No |

| Hawaii |

20% (non-refundable) |

$10.10 |

No |

| Idaho |

None |

$7.25 |

No |

| Illinois |

18% |

$9.25a |

No |

| Indiana |

9%e |

$7.25 |

No |

| Iowa |

15% |

$7.25 |

No |

| Kansas |

17% |

$7.25 |

No |

| Kentucky |

None |

$7.25 |

No |

| Louisiana |

5% |

Noneb |

No |

| Maine |

12%

25% (workers not raising children) |

$12.00 |

As of Jan. 2021 |

| Maryland |

28%f |

$11.00a |

No |

| Massachusetts |

30% |

$12.75a |

No |

| Michigan |

6% |

$9.65a |

No |

| Minnesota |

Avg. 37%g |

$10.00 (large businesses)

$8.15 (small businesses) |

Yes |

| Mississippi |

None |

Noneb |

No |

| Missouri |

None |

9.45a |

As of Jan. 2024 |

| Montana |

3% |

$8.65 (large businesses) $4.00 (small businesses)b |

Yes |

| Nebraska |

10% |

$9.00 |

No |

| Nevada |

None |

$8.25a (without health care coverage)

$7.25 (with health care coverage) |

Yes |

| New Hampshire |

None |

7.25 |

No |

| New Jersey |

40% h |

$11.00 a

$10.30 (seasonal and small businesses) |

As of Jan. 2025 |

| New Mexico |

17% |

$9.00 a |

No |

| New York |

30% i |

$11.80a |

As of Dec, 2021j |

| North Carolina |

None |

$7.25 |

No |

| North Dakota |

None |

$7.25 |

No |

| Ohio |

30% (non-refundable) |

$8.70 (large businesses)

$7.25 (small businesses) |

Yes |

| Oklahoma |

5% (non-refundable) |

$7.25 (large businesses) $2.00b (small businesses) |

No |

| Oregon |

9%

12% (workers with children under 3)k |

$11.25a |

As of Jul. 2023 |

| Pennsylvania |

None |

$7.25 |

No |

| Rhode Island |

15% |

$10.50 |

No |

| South Carolina |

41.67% (non-refundable)l |

Noneb |

No |

| South Dakota |

None |

$9.30 |

Yes |

| Tennessee |

None |

Noneb |

No |

| Texas |

None |

$7.25 |

No |

| Utah |

None |

$7.25 |

No |

| Vermont |

36% |

$10.96 |

Yes |

| Virginia |

20% (non-refundable) |

$7.25 |

No |

| Washington |

10% (when implemented)m |

$13.50 |

As of Jan. 2021 |

| West Virginia |

None |

$8.75 |

No |

| Wisconsin |

4% - one child

11% - two children

34% - three children

No credit - childless workers |

$7.25 |

No |

| Wyoming |

None |

$5.15b |

No |

| Puerto Rico |

Follows a separate schedule, credit between $300-$2,000 based on family sizen |

$7.25 $5.08o |

No |