Colorado’s so-called Taxpayer Bill of Rights, or TABOR, has contributed to a significant decline in that state’s public services. This decline has serious implications not only for the more than 5 million residents of Colorado, but also for the many millions of residents of other states in which TABOR-like measures are being promoted.

TABOR, a state constitutional amendment adopted in 1992, limits the growth of state and local revenues to a highly restrictive formula: inflation plus the annual change in population. This formula is insufficient to fund the ongoing cost of government. By creating a permanent revenue shortage, TABOR pits state programs and services against each other for survival each year and virtually rules out any new initiatives to address unmet or emerging needs.

In November, 2005, Colorado citizens voted to suspend the TABOR formula for five years, to stanch the deluge of harmful budget cuts. The decline in services in most major areas of state spending, including K-12 education, higher education, public health, and Medicaid from the time of adoption of TABOR until suspension of its formula — and the continuing consequences of those declines because in most areas the state has not been able to recover from the TABOR years — provide lessons for any other states considering adoption of a TABOR.

- Between 1992 and 2001, Colorado declined precipitously from 35th to 49th in the nation in K-12 spending as a percentage of personal income. As of 2006, the state maintained its low ranking among the states at 48th.

- Colorado’s average per-pupil funding fell by more than $600 relative to the national average between 1992 and 2006.

- Colorado’s average teacher salary compared to average pay in other occupations declined from 30th in the nation in 1992 to a low of 50 th in 2001, and edging up only slightly to 49th in the nation as of 2007.

- Under TABOR, higher education funding per resident student dropped by 31 percent after adjusting for inflation; after TABOR’s suspension, it declined by another 3 percent.

- College and university funding as a share of personal income declined from 35th in the nation in 1992 to 48th in 2004; Colorado maintains that ranking in 2008.

- Tuitions have risen as a result. Between 2002 and 2005, system-wide resident tuition increased by 21 percent (adjusting for inflation); since that time it has increased by 31 percent.

- Under TABOR, Colorado declined from 23rd to 48th in the nation in the percentage of pregnant women receiving adequate access to prenatal care, as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Colorado plummeted from 24th to 50th in the nation in the share of children receiving their full vaccinations. Only by investing additional funds in immunization programs was Colorado able to improve its ranking to 43rd in 2004 and to 23rd in 2008.

- At one point, from April 2001 to October 2002, funding got so low that the state suspended its requirement that school children be fully vaccinated against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (whooping cough) because Colorado, unlike other states, could not afford to buy the vaccine.

- Under TABOR, the share of low-income children lacking health insurance doubled in Colorado between 1992 and TABOR’s suspension, even as it fell in the nation as a whole. Colorado now ranks last 47th among the 50 states on this measure.

- TABOR has also affected health care for adults. Colorado fell from 20th to 48th for the percentage of low-income non-elderly adults with health insurance between TABOR’s enactment and suspension. By 2008, the state ranked only somewhat higher at 45th.

- In 2008, Colorado ranked 47th in the nation in the percentage of low-income children covered by Medicaid and 41st in the nation in the percentage of non-elderly low-income adults and by Medicaid.

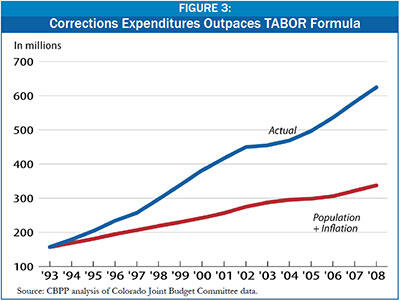

TABOR’s interaction with other areas of the state’s budget has created additional problems. Spending for corrections, for example, has grown substantially faster than the inflation-plus-population formula of TABOR, in part due to strict criminal codes and sentencing laws. Because spending for corrections has grown rapidly, other areas of the budget have been squeezed even more in order to keep overall spending under the strict TABOR limit.

Colorado Business and Community Leaders View TABOR as Deeply Flawed

A wide range of Coloradoans — business leaders, higher education officials, children’s advocates, legislators of both parties, and Former Governor Bill Owens (R), among others — recognize that TABOR has limited the state’s ability to fund critical services:

"Coloradoans were told in 1992 . . . that [TABOR] guaranteed them a right to vote on any and all tax increases. . . . What the public didn’t realize was that it would contain the strictest tax and spending limitation of any state in the country, and long-term would hobble us economically." — Tom Clark, Executive Vice President, Metro Denver Economic Development Corporation

"The [TABOR] formula . . . has an insidious effect where it shrinks government every year, year after year after year after year; it’s never small enough. . . . That is not the best way to form public policy." — Brad Young, former Colorado state representative (R) and Chair of the Joint Budget Committee

"[Business leaders] have figured out that no business would survive if it were run like the TABOR faithful say Colorado should be run — with withering tax support for college and universities, underfunded public schools and a future of crumbling roads and bridges." — Neil Westergaard, Editor of the Denver Business Journal

Colorado business leaders and citizens banded together and successfully campaigned to suspend TABOR beginning in 2006 and permanently change some of its most damaging features. It is unclear what will happen when the suspension expires, since in most areas Colorado still has not regained the services and quality of life it lost while TABOR was in effect.

The failure to regain services and the quality of life during the suspension reflects the difficulty of generating enough annual revenue to improve services in the aftermath of so many years of revenue starvation. There would have to be very robust and sustained revenue growth to allow the state to go beyond maintaining its current, low level of services and begin to recoup lost ground.

But while the suspension allows the state to retain the revenue it collects regardless of what the TABOR limit would have been, it left in place the TABOR restrictions on raising additional taxes. The reductions made in the TABOR years are still constraining revenues. In addition, the recession has reduced revenue collections in Colorado as it has done elsewhere. The key point, however, is that it is extremely difficult to restore services once TABOR has been in place for a long period of time.

Colorado’s experience provides an important cautionary tale for other states considering TABOR-like measures.

Evidence shows that Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights, or TABOR, contributed to a significant decline in the state’s public services. This has serious implications not only for the 5 million residents of Colorado, but also for the many millions of residents of other states in which TABOR-like measures are now being promoted.

This report documents TABOR’s effects on five major areas of Colorado government: K-12 education, higher education, public health, Medicaid, and corrections. It shows that Colorado’s national rankings in a number of areas of public services plummeted under TABOR and that it has been difficult to gain ground during the suspension of TABOR that began in 2006. It also presents statements by a range of Coloradoans — including public officials, business leaders, and independent experts — describing the damage TABOR has done to their state.

TABOR, a state constitutional amendment adopted in 1992 in Colorado, limits the growth of state and local revenues to a highly restrictive formula: inflation plus the annual change in population. This formula falls far short of being able to fund the ongoing cost of government. At a time when health care costs are growing much faster than inflation and the population is aging, TABOR’s inflation-plus-population formula forces annual reductions in the level of government services.

By creating what is essentially a permanent revenue shortage, TABOR pits state programs and services against each other for survival each year and virtually rules out any new initiatives to address unmet or emerging needs.

This is true even in good economic times. For example, from fiscal year (FY) 1997 through FY 2001, amidst a booming economy, Colorado refunded $3.25 billion in "excess" revenue to taxpayers as required by TABOR. (Whenever revenues for a given year exceed TABOR’s revenue limit, the extra amount must be returned to taxpayers.) Yet even as the state was giving up more than $3 billion in "excess" revenues, its services were deteriorating: average per-pupil funding for K-12 education was falling; several local public health clinics were forced to suspend prenatal services for low-income women because of insufficient program funding; and between April 2001 and October 2002 the state was forced to suspend its requirement that students be fully vaccinated against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (whooping cough) because Colorado, unlike other states, could not afford to buy the vaccine.

On a related point, it is important to note that the declines in services discussed in this report were not due to a lack of resources in the state. Colorado is both wealthy and well-educated. In 1995, a few years after TABOR began, Colorado ranked 11th in per-capita personal income among the states and its share of people 25 years or older with a bachelor’s degree or higher was largest in the nation. [1] The main reason Colorado’s services are declining is not due to its inability to raise sufficient revenues, but rather because TABOR restricts the state’s use of these revenues.

Coloradoans became increasingly disgruntled with effects of TABOR’s revenue limits. In the November 2004 election, the Republicans lost control of both chambers of the General Assembly for the first time since 1960; observers generally attribute this outcome in part to the legislature’s inability to craft a solution to relaxing TABOR. In November 2005, Coloradoans voted to enact

Referendum C, which (among other things) allowed the state to spend all revenues it collects under current tax rates for the next five years, even if those revenues exceed TABOR limits. The Referendum enjoyed broad support from a range of individuals and groups, including business leaders, children’s advocates, Republican and Democrat legislators, the Metro Denver Chamber of Commerce, and the conservative Colorado Springs City Council. [2] It has provided the state with much needed additional revenue for programs and services ($3.6 billion that wouldn’t have otherwise been available),[3] putting a halt to the rapid decline witnessed between TABOR’s enactment and suspension. Unfortunately, this has not been enough for the state to recover from the many years TABOR was in effect, and key programs and services continue to suffer.

Despite the lessons learned from Colorado, organizations dedicated to shrinking government are pushing for the adoption of TABORs in other states. Currently, Colorado is the only state with a TABOR.[4] In 2005, TABOR proposals were introduced in about half of the states. In 2006 in a similar number of states, TABOR proposals were introduced in legislatures or were the subject of petition drives. Three TABOR proposals made it to the ballot, in Maine, Nebraska, and Oregon, and all were defeated. TABOR made a second appearance in Maine in 2009 and was placed on the ballot in Washington that same year—both proposals were soundly defeated. Proposals continue to be considered in a number of states each year, but none have been adopted.

The following sections describe the impact TABOR has had in Colorado. Any state that follows Colorado’s example and adopts a TABOR could expect similar results.

TABOR contributed to a decline in Colorado’s K-12 education funding, with harmful effects across the state’s educational system.

Between 1992 and 2001, Colorado declined from 35th to 49th in the nation in K-12 spending as a percentage of personal income. [5] Thus, even as the state was becoming more prosperous during the economic boom of the 1990s, it was weakening its commitment to K-12 education. By 2006, K-12 spending as a share of personal income remained low, with Colorado ranking 48th in the nation on this measure.

Colorado’s average per-pupil K-12 funding fell from $379 below the national average in 1992 to $809 below the national average in 2001. [6] Colorado’s per-pupil funding in 2006 fell even further to $988 below the national average.

Between 1992 and 2001, Colorado declined from 30th to 50th in the nation in average teacher salary compared to average annual pay in other occupations.[7] By 2007, the state’s ranking remained low at 49th in the nation. Low teacher pay relative to other employment opportunities is likely to reduce the quality of teachers over time by making it harder to recruit and retain them.

In 2001, Colorado ranked 41st in the nation in the average number of students per teacher.[8] By 2006, its ranking among states declined to 42nd.

More than 90 percent of school children in the Denver metropolitan area were in overcrowded classrooms, according to a 2000 study by the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform.[9]

More than 90 percent of school children in the Denver metropolitan area were in overcrowded classrooms, according to a 2000 study by the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform.[9]

High school graduation rates fell between the time TABOR was adopted and Amendment 23, which boosted education funding (see below), was enacted. [10] Average graduation rates improved with Amendment 23, peaked in 2003-04, and then dropped back below levels of the early 1990s.

TABOR has weakened both local and state sources of K-12 funding. Even before TABOR’s 1992 enactment, the ability of local governments to fund education had been undercut by a property tax limitation adopted in 1982. The state had partially compensated for the resulting decline in local education funding by increasing its own funding. TABOR worsened this situation in two ways. First, it placed further restrictions on local governments’ control over their own revenue: TABOR limits the annual growth in local property tax revenue to the sum of inflation and a growth factor (such as the change in student enrollment), and it prevents local governments from raising property tax rates without voter approval. Second, by limiting the amount of revenues the state could keep, TABOR made it impossible for the state to maintain its own funding commitment to education — much less to continue making up for the loss of local funding. [11]

The underfunding of education had significant consequences for school districts, such as increased class sizes, textbook shortages, dirty classrooms (due to reductions in janitorial staff), and teachers having to buy their own classroom supplies.[12] By 2000, districts across the state were cutting back on their programs and services.

Colorado educators and analysts point out that low teacher pay — one result of the education funding squeeze under TABOR — impedes efforts to find and keep qualified teachers.

"The initial salary [makes it] very difficult to attract candidates." — Jack Krosner, Director of Human Resources for Douglas County.a

"After several years, [teachers] find that they are not getting ahead financially. Last year, we had a 17 percent teacher turnover, and that’s the primary reason." — Superintendent Mel Preusser, Eagle County School District.b

"[T]he main problem [associated with teacher salaries in Colorado] pertains to the ability to attract skilled teachers." — 2002 study by the Colorado Center for Tax Policy, an independent research organization, and the Daniels College of Business at the University of Denver.c

a Quoted in Bill Scanton, "Teacher Shortage on Horizon," Rocky Mountain News, February 2, 2000, p.A4.

b Quoted in Steve Lipsher, "Mountain Housing Costs Peak," The Denver Post, April 9, 2001, p.B4.

c Elisabetta Basilico, et al., "Teacher’s Salaries in Colorado: Reasons, Consequences, and Alternatives for Below Average Compensation," July 2002, www.cpeccenterfortaxpolicy.org/reports/02-teachers_salaries.pdf.

As just one example, Adams 12 school district, located about seven miles from downtown Denver, was forced to impose reductions in teacher salaries, classroom supplies, transportation, and nursing and psychological services. The district also had to eliminate funding for full-day kindergarten and increase sports fees.[13]

These cuts occurred at the same time the state was providing millions of dollars of refunds to Colorado taxpayers, as required by TABOR. The state refunded $679 million in tax revenues in 1999 and $941 million in 2000.

As Coloradoans saw the damaging effects of the decline in K-12 funding, they put a constitutional amendment on the ballot in November 2000 that would require the state to increase per-pupil funding by at least one percent above inflation each year for ten years, and by at least inflation thereafter. This amendment, known as Amendment 23, passed.

The problem, however, is that Amendment 23 does not provide Colorado with enough money to get out of the hole caused by past underfunding. As evidence of this, Colorado’s K-12 funding rose temporarily after Amendment 23’s enactment and then fell back. The state spends several hundred dollars less per pupil than the national average (Figure 1). And while Colorado’s per-capita personal income is 8 percent above the national average, average salaries for Colorado teachers were nearly 11 percent below the national average in 2007.[14]

Under TABOR, higher education funding in Colorado declined significantly — by a larger amount, in fact, than any other major program area. [15]

Between 1992 and 2004, Colorado declined from 35th to 48th in the nation in higher education funding as a share of personal income; as of fiscal year 2008, Colorado continued to rank 48th among the 50 states on this measure. In 1992, Colorado spent close to the national average on higher education by this measure but declined to just 57 percent of the average in 2004 and 59 percent in 2008 (see Figure 2).

Between 1992 and 2004, Colorado declined from 35th to 48th in the nation in higher education funding as a share of personal income; as of fiscal year 2008, Colorado continued to rank 48th among the 50 states on this measure. In 1992, Colorado spent close to the national average on higher education by this measure but declined to just 57 percent of the average in 2004 and 59 percent in 2008 (see Figure 2).

Between 1995 and 2005, higher education funding per resident student in Colorado dropped by 31 percent (from $5,765 to $3,961) after adjusting for inflation.[16] In FY2009, system-wide higher education funding per resident student in Colorado reached a 15-year low, after adjusting for inflation.

The decline in funding per resident student during the 1995 to 2005 period affected all schools in the state higher education system. Funding declines ranged from 41 percent at the University of Colorado system to 21 percent at the community college system (see Table 1). After suspension of the TABOR formula in 2005 through Referendum C, the state support for higher education continued to decline, but at a much less rapid rate of 3 percent system-wide.

To compensate partially for decreased state funding, most public higher education institutions have raised tuition in recent years. Between FY-2002 and FY-2005, system-wide resident tuition (adjusted for inflation) increased by 21 percent. At certain schools, however, tuition increases were much greater. For instance, during this same time period, tuition increased 31 percent for residents in the University of Colorado system, 32 percent for residents at Fort Lewis College, 30 percent for residents at the Colorado School of Mines, and 28 percent for residents at the University of Northern Colorado. Increases in tuition have grown even more since FY2005. Across the public system of higher education, tuition per resident student grew by 31 percent by FY2009.

| TABLE 1:

HIGHER EDUCATION FUNDING HAS PLUMMETED

General Fund Appropriations per Resident Student (adjusted for inflation) |

| | | Percent Change |

| FY1994-95 | FY2004-05 | FY2008-09 | FY95-FY05 | FY05-FY09 | FY95-FY09 |

| University of Colorado System | $8,139 | $4,820 | $4,458 | -41% | -8% | -45% |

| Colorado State University System | $8,088 | $5,683 | $5,334 | -30% | -6% | -34% |

| University of Northern Colorado | $5,291 | $3,794 | $4,073 | -28% | 7% | -23% |

| Colorado School of Mines | $9,377 | $7,103 | $7,121 | -24% | 0% | -24% |

| State Colleges (Adams, Mesa, Western, Metro) | $4,301 | $3,301 | $3,513 | -23% | 6% | -18% |

| Fort Lewis College | $4,052 | $3,178 | $3,610 | -22% | 14% | -11% |

| Community Colleges | $3,369 | $2,678 | $2,605 | -21% | -3% | -23% |

| System Wide | $5,765 | $3,961 | $3,833 | -31% | -3% | -34% |

| Source: CBPP Analysis of Colorado Joint Budget Committee Appropriations data and Legislative Council Staff enrollment data. |

Even after taking these tuition increases into account, higher education funding has still decreased in recent years. Total funding per full-time resident student — the combination of General Fund appropriations and tuition — declined by 13 percent between FY-2002 and FY-2005 and another 13 percent between FY2005 and FY2009.[17]

As described below, the harmful effects of the decline in funding rippled through the state’s higher education system. They also created considerable worry among the state’s business leaders (see box). David Longanecker, Executive Director of the Western Interstate Commission on Higher Education, recently noted, "I’m often quick to say the sky is not falling. Now, I can’t find the data that suggests Colorado is not in trouble. I was in Arizona recently before a state higher-education board, and they were saying, ‘Life could be worse — we could be in Colorado.’" [18]

Faced with steadily decreasing funding, higher education institutions were forced to take a series of painful steps. For example, between 2002 and 2004 the University of Colorado (CU) laid off 286 faculty and staff and eliminated six academic programs. As of December 2004, construction funding had been cut by $121 million for projects underway at CU, even though CU was already facing a $400 million maintenance backlog.

At Colorado State University (CSU), 54 faculty were lost in 2004 to budget cuts. Between 1990 and 2005, a total of 80 faculty positions went unfilled, even as enrollment grew 20 percent. Also, CSU reported losing 32 tenured faculty in 2002 because it could not match offers from other colleges. CU lost 16 tenured professors in 2004, twice the usual number, because they were recruited by colleges offering higher salaries. [19]

Emphasizing that investment in higher education is a key part of a successful economic development strategy, Colorado’s business leaders expressed widespread concern about the state’s funding cutbacks.

"The bottom line is that institutions of higher learning in Colorado will continue to suffer funding shortfalls under the present system. If you ask the business community, a strong system of higher education is at the top of the list for economic development and the creation of jobs." — Dick Robinson, CEO of Robinson Dairy and member of the Colorado Economic Futures Panel.a

"[Colorado’s higher education] system is at risk. The way we’re going — because of TABOR and Amendment 23 — we’re going to be basically out of public funds. . . . [S]peaking from a business standpoint, we’re concerned because our success depends on the quality of the higher education system." — Raymond Kolibaba, Vice President of Space Systems, Raytheon Company.b

"A lack of publicly-funded higher education institutions could leave our high school graduates without affordable higher education options, further exacerbating our struggles to ‘grow our own’ highly educated workforce. At the same time, our businesses could be left uncertain about the resources flowing from higher education institutions." — The Public Education and Business Coalition.c

"[K]ey businesspeople and community leaders tell us . . . [t]hey are looking at the broader issues that will shape the future of Colorado, from the well-being of our higher education centers to the availability of skilled workers as our economy improves." — Bruce Alexander, President and CEO of Vectra Bank Colorado, commenting on a July 2005 survey showing that 71 of 100 Colorado business leaders identified TABOR as their top concern. d

"For businesses to be successful, you need roads and you need higher education, both of which have gotten worse under TABOR and will continue to get worse." — Tom Clark, Executive Vice President of the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce.e

a Dick Robinson, "Solutions to Funding Colorado’s Colleges," The Denver Post, April 17, 2005, p. E5.

b Quoted in Suzanne Weiss, "Colorado Leaders on Education. Picking Their Brains," HeadFirst, May 12, 2005, www.headfirstcolorado.org/adm/view_article.php?story_id=132. Another article reported that Kolibaba recently told Colorado lawmakers that he has seen firsthand the problems caused by cuts to higher education. He said that he is having trouble bringing workers to Colorado and recruiting at local colleges because of deep cuts the state was forced to make in areas people consider important to their quality of life. Steven Paulson, "Debate begins over fixes to state’s economic woes," The Associated Press, February 2, 2005.

c The Public Education and Business Coalition, "Investing in the Next Generation: How Education Drives Colorado’s Economic Future," November 2004, www.pebc.org/ourwork/policy/ed-econ.pdf.

d Quoted in "New Survey Shows TABOR is Top Concern Among Colorado Business Leaders; Vectra 100 Survey to Track Issues and Views among Influential Executives," Business Wire, July 12, 2005.

e Quoted in Daniel Franklin and A.G. Newmyer III, "Is Grover Over?," Washington Monthly, March 2005.

Prior to the enactment of Referendum C in November 2005, school officials predicted that things would have gotten even worse. University of Colorado president Hank Brown said that "if C doesn't pass, there will be no aid for higher education a decade from now... and tuitions would eventually rise to what they are at private universities." Colorado State University president Larry Penley expressed similar sentiment, "Colorado State University could become a private school if voters don't support budget reform." [20]

In November 2005, Colorado voters approved "Referendum C," which temporarily suspended the formulaic limitation on revenue growth and thus allowed Colorado to spend all the revenue it would collect over the next five years. Colorado would not have to refund all revenue that exceeded the limitation. If the referendum had not passed, Colorado would have had to make sharp reductions in spending at the same time it was sending large refunds to taxpayers.

The ability to retain and use all the revenues that the existing tax system yields based on economic growth generally allowed Colorado to avoid further reductions in services. But it did not give the state the wherewithal to restore most of the services lost over the more than a decade TABOR had been in effect. The normal growth in revenues can sustain services but — unless economic growth is unusually strong — cannot support improvements in services. For that, an increase in taxes normally is required. And the TABOR requirement that a vote of the people is necessary to increase taxes was not suspended by Referendum C, and no such vote has occurred since the approval of Referendum C.

Moreover, the recession interrupted what progress in restoring services might have been made during the TABOR time out. Like almost every other state, Colorado has had to struggle to close large deficits; in fiscal year 2010 Colorado’s deficit equaled more than one-fifth of its budget, following on a deficit equal to 14 percent of its budget in fiscal year 2009.

Colorado has made service improvements in a few areas since TABOR’s suspension — most notably in health insurance coverage for children. Before the suspension, Colorado’s health insurance program for low-income children, known as CHP+, was one of the most restrictive of any of the state programs established under the federal-state Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). It now covers children up to 205 percent of the poverty level, and Colorado ranks 21st in the national in its coverage of low-income children under SCHIP.

For the most part, however, as illustrated in this report, Colorado remains stuck at the low level of services to which it had fallen under TABOR. Once TABOR has been in effect for a number of years, and has year-by-year reduced the ability of a state to provide services, it is extremely difficult to reverse its consequences and climb out of the hole.

Public health programs suffered under TABOR as well. Between FY-1992 and FY-2004, state funding for the Department of Public Health and Environment declined by one-third as a share of personal income, even as Colorado’s population grew rapidly. [21]

The underfunding of Colorado’s public health system has had serious consequences.

Between 1995 and 2003, Colorado declined from 24th to 50th in the nation in the share of children who receive their full vaccinations. Unvaccinated children are at much greater risk of getting measles and whooping cough. Moreover, medical research shows that vaccinated children are much more likely to get these diseases when they live in areas with unvaccinated children. While several factors determine a state’s immunization rate, a recent Colorado Health Institute study concluded that "spending restrictions" are a factor in Colorado’s low ranking, since TABOR does not give Colorado the same flexibility as other states to meet changing needs. [22] By 2007-08, after the suspension of TABOR’s revenue growth formula, Colorado’s ranking on this measure had improved substantially, to 23rd in the nation.

"Not having funding does translate to difficulty in promoting immunizations" — Ned Calonge, Chief Medical Officer, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.a

"It really is a travesty that a state as wealthy as Colorado and with as high an educational level has more restrictive health policies than Mississippi, Alabama, Texas, Wyoming, [and] New Mexico. It’s just inexcusable" — Dr. Stephen Berman, Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and former President of the American Academy of Pediatrics.b

a Quoted in "Costs of Complacency," Governing, February 2004, p. 26-8, 30-2, 34-5.

b Quoted in Diane Carman, "Bad policies aid and abet a killer: flu," The Denver Post, December 7, 2003, p. B1.

From April 2001 to October 2002 the state was forced to suspend its requirement that students be fully vaccinated against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (whooping cough) because Colorado, unlike other states, could not afford to buy the vaccine. [23]

Between 1992 and 2002, Colorado declined from 23rd to 48th in the nation in access to adequate prenatal care, a sign of funding shortages in local health clinics. In an effort to increase access to prenatal care for low-income women, the state launched the Prenatal Plus Program in 1996, but financial pressures have forced the closing of a number of local sites. [24] Since 2002, the share of women receiving adequate prenatal care in Colorado has deteriorated from 67.3 percent to 64.5 percent in 2006.

Among the casualties of the decline in public health funding was a state program that provided local public health agencies with vital revenues. The canceling of this program in 2002 forced many counties to eliminate a range of services, from immunization clinics to car-seat safety education. While plummeting state revenues during the 2001-2002 economic downturn were the immediate cause of the program’s cancellation, TABOR has cemented this cut in place and prevented the restoration of funding. [25]

Funding cuts like these forced public health agencies to make difficult tradeoffs. "Because per capita and county dollars fund our core public health services, there were no good choices to be made," said Dr. Adrienne LeBailly, director of the Larimer County Department of Health and Environment. [26]

Larimer County responded to the shortfall by, among other things, eliminating hazardous waste inspections and inspections of leaking underground storage tanks; reducing health inspections of restaurants, school cafeterias, and grocery stores; closing a clinic designed to help at-risk children

thrive in their home environment; scaling back health-care programs for special-needs children and prenatal risk reduction; and reducing public-information and tobacco-prevention services.[27] While some funding was later restored, these cuts in services seriously hindered the department’s ability to provide health services to the county.

TABOR also hindered Colorado’s ability to provide health coverage to its vulnerable residents through Medicaid and related health care programs, and the state has made little improvement since 2005. Unlike education and public health, Medicaid did not experience large funding declines in dollar terms under TABOR. Nevertheless, Colorado (like other states) has faced critical health-care challenges posed by the steady erosion of employer-sponsored health coverage and rising health-care costs due to recession. Unlike other states, Colorado also had to contend with TABOR, which left it without the necessary resources to meet these challenges and in a deep hole that will take some time to climb out of.

Between 1992 and 2004 the share of low-income children lacking health insurance doubled in Colorado (from 16 percent to 32 percent) even as it fell in the nation as a whole (from 21 percent to 18 percent). By 2008 the share of Colorado’s low-income children lacking health insurance had dropped from the 32 percent in 2004 to 23.2 percent. Nevertheless, Colorado ranked 47th among the states on this measure.[28]

In Colorado, the percentage of low-income adults under 65 without health insurance rose from 31 percent in 1992 to 46 percent in 2004, dropping its ranking from 20th to 48th. By 2008, the uninsurance rate among nonelderly adults had barely improved to 45.9 percent and the state ranked 45 th in the nation.[29]

In 2008, Colorado ranked 41st in the nation in the percentage of low-income adults under 65 and 47th in the percentage of low-income children covered by Medicaid.[30] This indi cates that in Colorado Medicaid is not fully performing the function for which it was designed.

Consequently, low-income adults and children are much more likely to be uninsured in Colorado than in the nation as a whole (Table 2). [31]

| TABLE 2:

LOW MEDICAID COVERAGE AND HIGHER UNINSURANCE RATES

Low-Income Individuals, 2008 |

| | Colorado | US |

| Low-Income Adults Under 65 Who Are Covered by Medicaid | 15.3% | 20.5% |

| Low-Income Children Who Are Covered by Medicaid | 36.4% | 54.2% |

| Low-Income Adults Under 65 Who Are Uninsured | 45.9% | 40.2% |

| Low-Income Children Who Are Uninsured | 23.2% | 15.9% |

Simply put, Colorado’s Medicaid program remains one of the most limited in the country. "For the most part, the Colorado Medicaid program is a ‘bare bone’ program providing mainly the federally required services for federally required populations," the Colorado Joint Budget Committee staff noted recently.[32] For example: In Colorado, a working family of three was ineligible for Medicaid in 2009 if its income exceeded $12,060, which was just 66 percent of the poverty line. [33]

Colorado is one of only 15 states that did not have a "medically needy" Medicaid option, which provides coverage to people whose gross income modestly exceeds Medicaid limits but who have high medical bills that reduce their disposable income below Medicaid limits.

[34]Colorado is one of only six states that imposed an asset test on children applying for Medicaid. Until 2006 in Colorado, children whose families had more than $2,500 in assets were ineligible for Medicaid, no matter how low the family’s income was.[35]

Since the TABOR formula was suspended, Colorado did make a big improvement in its separate health program for low-income children, known as CHP+, which under TABOR was one of the most restrictive of any of the state programs established under the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). It now covers children with incomes up to 205 percent of the poverty level, scheduled to rise to 250 percent of poverty. Colorado now ranks 21st in the nation in its coverage of low-income children under SCHIP.[36]

There may be further Medicaid improvements in the future. In 2009 Colorado enacted a Hospital Provider Fee — which is a fee rather than a tax and thus does not require voter approval. If the structure of the fee is approved by the federal government, the proceeds of the fee would be used to improve the state’s Medicaid program.

TABOR Weakens and Limits Medicaid

Experts agree that TABOR is a key reason why Colorado could not adequately address its problems of below-average Medicaid coverage and above-average percentages of uninsured residents.

"Improving access to affordable insurance is a particularly difficult problem in Colorado because of limitations on increasing state spending by virtue of the TABOR Amendment. . . . Even though Colorado was eligible to receive up to $42 million in federal matching funds in 1998, we could produce only $7 million in state funds and ended up with a small fraction of what could have been ours." — Dr. Gary VanderArk, Coalition for the Medically Underserved.a

"[The reason the state did not provide Medicaid coverage to more children] was absolutely not the recession, because at the same time, we were giving money back to the taxpayers — $100, $200, $300. In return for that, we had 190,000 uninsured children, half of whom would potentially be eligible for Medicaid or the child health plan, yet we weren’t able to get these kids health insurance because we didn’t have the budget flexibility under TABOR." — Dr. Stephen Berman, University of Colorado School of Medicine.b

"[B]udgetary constraints such as those resulting from the Taxpayers Bill of Rights Amendment (TABOR), combined with increasing medical costs, make the further erosion of government program reimbursements [to health-care providers] a stark reality. Such erosion will only serve to further perpetuate the escalation of uncompensated care, insurance premiums and, ultimately, the ranks of those unable to afford private coverage." — Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce.c

a Dr. Gary VanderArk, "Rx for the Uninsured: Casting a safety net for the indigent," The Denver Post, February 28, 1999, p. J1.

b Dr. Stephen Berman, Interview, June 2005.

c Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce, "Medicaid, the Uninsured and the Impact on Your Business," 2001, www.denverchamber.org/chamber/paffairs/Whitepaper.pdf.

Corrections spending grew at an average annual rate of 9.6 percent between 1992 and 2008, substantially faster than TABOR’s inflation-plus-population formula.[37] Corrections spending in 2008 alone was $288 million more than it would have been if it had remained within the TABOR limit since TABOR’s enactment (see Figure 3).

Corrections’ seeming immunity to TABOR is due to the fact that it is governed by state criminal codes and sentencing laws. If state law says that a certain crime mandates a certain sentence, the Department of Corrections must comply by imprisoning the offender and assuming the associated costs (housing, security, food service, medical care, and so on).

The main reason for the large growth in corrections spending has been what the Department of Corrections terms "unprecedented growth" in the inmate population. Between 1985 and 2009, Colorado’s inmate population has increased a staggering 547 percent or nearly ten times the increase in the general population (57 percent). Since TABOR’s adoption, the prison population has grown more than two and a half times as fast on average (6.1 percent per year) as the general population (2.2 percent per year).

TABOR’s harmful effects on Colorado became increasingly clear, as these statements from 2004 and 2005 by key Coloradoans show.

"Now, as the economy has slowly begun to recover, we are learning that the revenue and spending limits imposed by TABOR curb the recovery of our public-sector budgets to the point where the state is challenged in its efforts to adequately provide services such as higher education, health care and transportation. Because of the negative economic impact of this strain, the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce supports fiscal reforms that allow the state budget to recover, while promoting responsible, limited government." — Denver Metro Chamber of Commercea

"Coloradoans were told in 1992 . . . that [TABOR] guaranteed them a right to vote on any and all tax increases. . . . What the public didn’t realize was that it would contain the strictest tax and spending limitation of any state in the country, and long-term would hobble us economically." — Tom Clark, Executive Vice President, Metro Denver Economic Development Corporationb

"While the economy is expected to grow in fiscal year 2005-06 and General Fund revenues will increase 5.5 percent, the amount of General Funds available under current law is approximately $80 million or a 1.4 percent increase. . . . In FY 2005-06, $80 million only covers about 54 percent of the expected growth in Medicaid and K-12 education, leaving those programs under-funded and the remaining state priorities without any funding." — Governor Bill Owensc

"The [TABOR] formula . . . has an insidious effect where it shrinks government every year, year after year after year after year; it’s never small enough. [A]t some point you’ll be cutting services that people will start objecting to, and that’s when change happens. That is not the best way to form public policy." — Brad Young, former Colorado Representative (Republican) and Chair of the Joint Budget Committeed

"When TABOR was enacted, roughly 25 percent of the state budget went to funding higher education; it is now under 10 percent. . . . Without TABOR reform there is only one result — the end of state funding for higher education by the end of the decade." — Michael Carrigan, University of Colorado Regente

"[Business leaders] have figured out that no business would survive if it were run like the TABOR faithful say Colorado should be run — with withering tax support for college and universities, underfunded public schools and a future of crumbling roads and bridges." — Neil Westergaard, Editor of the Denver Business Journalf

a Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce, "Statement on TABOR," March 2005, www.denverchamber.org/paffairs/tabor.asp

b Quoted in "The Real Story Behind TABOR," DVD, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 2005.

c Governor Owens, "Submission of FY 2005-06 Budget to the Joint Budget Committee," November 9, 2004, www.state.co.us/gov_dir/govnr_dir/ospb/governorsbudget/govbudgetreq05-06.pdf .

d Quoted in "The Real Story Behind TABOR," DVD, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 2005.

e Michael Carrigan, interview by ColoradoPols, March 2005, http://coloradopoliticalnews.blogs.com/colorado_political_news/2005/03/qa_with_cu_rege.html .

vi Neil Westergaard, "Business folks fed up with TABOR worship," Denver Business Journal, July 22, 2005.

The growth in the inmate population partly reflects 1985 legislation that doubled the maximum sentence for felonies. As a result of this legislation, the average length of stay for new inmates nearly tripled. Subsequently the legislature attempted to slow the growth in the inmate population by relaxing certain sentencing policies, but with only limited success.

So quickly has the prison population grown that even the large increases in state corrections spending have not been able to keep up. Colorado’s corrections facilities were operating at nearly

110 percent of design capacity as of 2008.[38] This is not sustainable: overcrowded prisons can bring a host of problems, from escalating violence to increased litigation by inmates. To rectify the situation, the Department of Corrections will need even more money to expand facilities. Even so, overcrowding is likely to continue.

While Colorado is not the only state facing a rapidly increasing prison population and the associated financial burdens, it is the only state with a TABOR, and that has put Colorado in a terrible bind. Under TABOR, if spending grows faster than the inflation-plus-population formula in one area of the budget — such as corrections — then other budget areas, such as education and/or public health, must be squeezed even more to keep overall spending within the TABOR limit. As the Colorado Legislative Council noted, "If inmate population growth exceeds the state’s population growth (assuming inflation affects the TABOR limit and departmental costs in the same amount), expenditures of the department may exceed the TABOR limit and create additional budgetary pressure for the legislature to meet the aggregate TABOR spending limit."[39]

TABOR slowly starves the services on which state residents rely. Each year, the TABOR formula produces a maximum expenditure level that is below what is needed, and all state priorities must compete for this inadequate level of funding. If one area, such as corrections, gets first in line because of legal requirements, the funding available for all other services shrinks further. While the cuts in any one year may be modest, the cumulative effect of annual reductions over a number of years is devastating.

Some 13 years after the adoption of TABOR, Colorado strongly felt the consequences of this progressive starvation and suspended TABOR;s limit on revenue growth. As described in this report, services had deteriorated to the point at which the quality of life in the state had been undermined — and the state’s potential for economic development had been weakened. While some services such as children’s health insurance were able to be improved after the suspension, many — including education — have not recovered from the many years of constraint under TABOR. What has happened in Colorado should be a cautionary tale for any other state considering going down the TABOR path.

More than 90 percent of school children in the Denver metropolitan area were in overcrowded classrooms, according to a 2000 study by the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform.

More than 90 percent of school children in the Denver metropolitan area were in overcrowded classrooms, according to a 2000 study by the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform. Between 1992 and 2004, Colorado declined from 35th to 48th in the nation in higher education funding as a share of personal income; as of fiscal year 2008, Colorado continued to rank 48th among the 50 states on this measure. In 1992, Colorado spent close to the national average on higher education by this measure but declined to just 57 percent of the average in 2004 and 59 percent in 2008 (see Figure 2).

Between 1992 and 2004, Colorado declined from 35th to 48th in the nation in higher education funding as a share of personal income; as of fiscal year 2008, Colorado continued to rank 48th among the 50 states on this measure. In 1992, Colorado spent close to the national average on higher education by this measure but declined to just 57 percent of the average in 2004 and 59 percent in 2008 (see Figure 2).