The House is set to begin consideration this week of a bill to expand and make permanent the Research and Experimentation (R&E) tax credit. The bill represents the latest installment in a series of bills that House leaders are expected to move to make permanent costly “tax extenders,” a set of tax provisions that policymakers routinely extend for a year or two at a time, most of which expired at the end of 2014. The House has already passed three bills this year to make permanent eight provisions at a ten-year cost of $127 billion. Expanding and making permanent the R&E credit, one of the biggest business tax extenders, would add another $177 billion to the deficit over the next decade.[1] Further, it would send the message that such costly, primarily corporate, measures can be made permanent without offsetting their cost, thus opening the door for other provisions to be made permanent (and expanded).

The House approach to making these extenders permanent isn’t fiscally responsible. It also places extending these tax breaks above extending key provisions of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit (CTC) that benefit tens of millions of low- and middle-income working families (and are slated to expire at the end of 2017). For these reasons, the President and many House members opposed an effort last fall to make the extenders permanent without paying for them. The action now underway in the House is a reprise of that effort, and the President has threatened each of the previous bills the House has voted on as well.

House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Paul Ryan has made clear that House Republican leaders are simply “picking up where we left off last year” and that “[w]e’re going to do more markups in the future,” indicating that the measures due for House consideration are only one part of a larger effort to make most of the extenders permanent.[2]

Lawmakers may support making particular extender provisions permanent on policy grounds. They should recognize, however, that doing so now without offsetting the costs would (and is designed to) open the door for even more extenders — most of them corporate tax breaks — to be made permanent. For example, the President threatened to veto House-passed bills to make charitable and business extenders permanent, explaining that while he supports measures to help charitable organizations and small businesses, he rejects the House approach of making such tax breaks permanent without offsetting their cost while taking no action to make the key EITC and CTC provisions permanent.[3]

Moreover, the House approach stands in sharp contrast to the bipartisan understanding (which GOP leaders insist upon) that any easing of sequestration to avert damaging cuts in economically important areas like education and training, basic scientific research, and infrastructure must be fully paid for — or else it won’t pass. The extenders should not be granted a more generous fiscal standard.

In short, the House leadership’s approach represents both ill-advised fiscal policy and misguided priorities.

The House approach would:

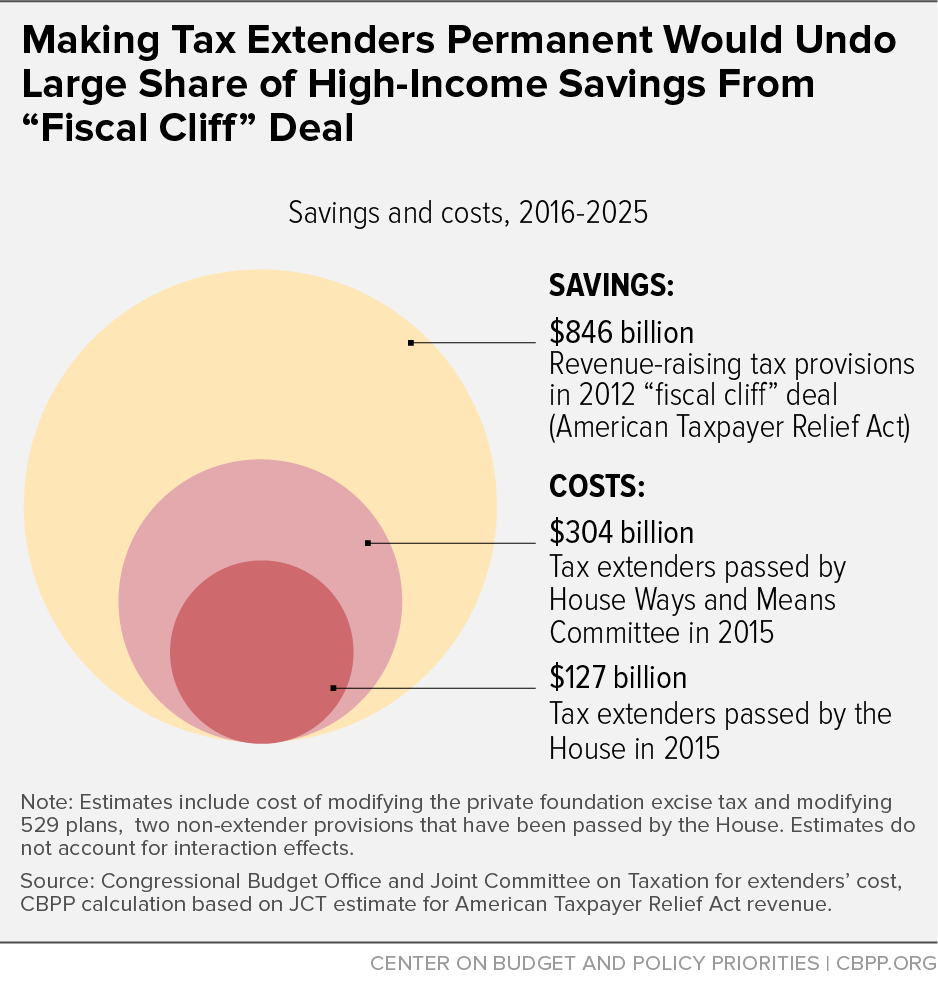

- Undo most of the savings from recent deficit-reduction legislation. Last year the House passed a series of permanent tax-extender bills, along with a bill to expand and permanently extend bonus depreciation, which together would have given back nearly three-quarters of the revenue raised by the 2012 “fiscal cliff” legislation. The House has begun this process anew by passing provisions that would reduce revenues by $127 billion over 2016-2025. Expanding and making permanent the R&E credit would more than double the total cost of bills passed by the House to $304 billion.

- Place the tax extenders ahead of other, more critical tax provisions scheduled to expire in coming years. These include key elements of the EITC and CTC for low-income working families. If those measures expire, more than 16 million people in low-income working families, including 8 million children, would fall into — or deeper into — poverty. And some 50 million Americans would lose part or all of their EITC or CTC.[4] A growing body of evidence links income from these tax credits to improvements in children’s health, educational attainment, and employment and earnings later in life.[5]

- Bias tax reform against reducing deficits. Policymakers are expected to attempt to pass corporate tax reform this year. If they make the extenders permanent in advance of tax reform, a reform plan would no longer have to offset the extenders’ cost to achieve revenue neutrality. This would free up hundreds of billions of dollars in tax-related offsets over the decade that policymakers then could channel toward lowering the corporate tax rate more sharply or closing fewer dubious corporate tax breaks, while still claiming revenue neutrality. If that occurred, the result would be to lock in substantially larger deficits than would occur under revenue-neutral corporate tax reform that pays for those extenders it keeps and makes permanent.

Since the fall of 2010, policymakers have enacted four major pieces of deficit-reduction legislation[6] that will reduce projected deficits by several trillion dollars, mostly from program cuts.[7] The revenue contribution to deficit reduction stems almost entirely from the 2012 “fiscal cliff” legislation — the American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA) — which will raise $846 billion over 2016-2025.[8]

The House has already voted to start giving back those deficit savings by making permanent eight tax provisions, at a cost of $127 billion over 2016-2025.[9] Expanding and making permanent the R&E credit would add another $177 billion to this cost, and it’s likely to be followed by other primarily corporate provisions. Altogether, these Ways and Means-approved bills total $304 billion in tax cuts, giving back more than one-third of the revenue ATRA raised (see Figure 1). More than four-fifths of these tax breaks benefit businesses.

These bills are part of an expected effort by House leaders to make almost all of the extenders permanent in advance of tax reform, without offsetting their cost. Making all extenders permanent, including those that Ways and Means has already permanently extended (and in some cases expanded), would cost more than $500 billion over 2016-2025, giving back more than half the revenue ATRA raised.[10]

The House also voted last year to make bonus depreciation (which is not a traditional tax extender) permanent and to expand it.[11] Adding bonus depreciation to the extenders provisions would raise the cost over 2016-2025 to at least $700 billion, more than four-fifths of the total “fiscal cliff” savings.

While some claim that policymakers have never paid for the extenders, this is mistaken. These measures were extended as part of large budget deals in 1990 and 1993 that shrank deficits overall by hundreds of billions of dollars, effectively offsetting the extenders’ cost. A smaller stand-alone bill, the 1991 Tax Extension Act, also paid for the extenders it continued. This practice subsequently fell into disuse, although lawmakers launched some efforts to re-apply “pay-as-you-go” rules to the extenders, and in 2008 and 2009 the House passed tax-extender legislation that was paid for.

Recent efforts to make tax extenders permanent have turned the traditional extenders debate — about continuing these provisions for a year or two — into a discussion about which expiring tax provisions to extend permanently. When policymakers consider which expiring provisions should receive permanent status, they should accord top priority to three important CTC and EITC provisions scheduled to expire at the end of 2017, which: 1) allow more working-poor families to qualify for a full or partial CTC (previously, the CTC largely or completely shut out millions of working-poor families, the very families that most need the credit); 2) deliver more adequate EITC “marriage-penalty” relief; and 3) enable low-income working families raising more than two children to receive a somewhat larger EITC.

Instead, the House approach has been to make tax extenders permanent, primarily benefiting businesses, while doing nothing to maintain these CTC and EITC provisions. If these provisions expire:

- A woman raising two children on full-time, minimum-wage earnings would lose her entire Child Tax Credit. A single mother with two children working full time at the minimum wage and earning $14,500 would lose all of her $1,725 CTC. Moreover, the earnings that a family needs to qualify for even a tiny CTC would jump from $3,000 to $14,700, and the earnings needed to qualify for the full CTC (of $1,000 per child) would rise to more than $28,000 for a married couple with two children — up sharply from $16,330 under current policy. As a result, many low-income working families that would still qualify for the CTC after 2017 would see their credit cut dramatically. For example, a family with two children earning $20,000 would see its CTC cut from $2,000 to $795.

- Many married couples would face higher marriage penalties or a cut in their EITC. To reduce marriage penalties, the income level at which the EITC begins to phase out is now set $5,000 higher for married couples than for single filers. After 2017, it would be set $3,000 higher, which would shrink the EITC for many low-income married filers and increase the marriage penalty for many two-earner families.

- Larger families would face a cut in their EITC. After 2017, the maximum EITC for families with more than two children would be cut over $700, by lowering it to the level of the maximum EITC for families with two children.[12] Costs rise with family size, but wages do not; partly as a result, 36 percent of all children live in families with more than two children, but 50 percent of poor children do.

As noted earlier, letting these provisions expire would have a substantial impact on low- and moderate-income working families, pushing more than 16 million people — including 8 million children — into, or deeper into, poverty.[13] It would also result in a reduction in tax credits for some 50 million people, effectively shrinking after-tax pay from work for millions of low- and middle-income families.

A key measure of any tax reform package is its impact on long-term deficits. Given the country’s long-term fiscal pressures, the Obama Administration and many fiscal policy analysts have said that part of the savings from reducing inefficient tax subsidies should go to reducing deficits and the growth of debt.

In contrast, former House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp called for revenue-neutral tax reform, meaning that all savings from reducing tax subsidies would go to reducing tax rates and other taxes. (While the Camp proposal was roughly deficit-neutral in the initial ten years, it likely increased deficits after that.)[14]

Similarly, the recently passed congressional budget resolution assumes that revenues will continue at levels consistent with current law, thereby assuming that any tax-reform plan would be revenue neutral and that policymakers would offset the cost of any extenders they chose to renew. This level of revenue and nearly $5 trillion of program cuts between 2016 and 2025 were needed to reach the stated goal of balancing the budget by the end of the decade.[15] (Of course, making the extenders permanent now without offsetting their cost would violate this budget plan and balanced-budget goal.)

Making the extenders permanent without offsets would also be the first step toward redefining revenue neutrality for corporate tax reform in a way that locks in higher long-term deficits. For instance, the Camp tax reform plan would have paid for the temporary tax provisions it chose to make permanent, such as the R&E credit.[16] But if policymakers make the extenders permanent now, a future tax reform plan will no longer have to offset the extenders’ significant cost in order to achieve revenue neutrality.

In fact, that appears to be Chairman Ryan’s goal. Following the House passage of a business tax extenders bill, he stated, “I see this as a down payment on a simpler, flatter, fairer tax code.”[17] Making the extenders permanent now allows policymakers to use savings that otherwise would have been needed to offset the extenders’ cost to cut the top tax rate more deeply and/or to rein in fewer unproductive or lower-priority tax breaks — at the cost of higher deficits.

Ultimately, such action would also heighten pressures to cut public investments and social programs to help address the long-term fiscal challenges that these fiscally irresponsible tax policy actions would have worsened.