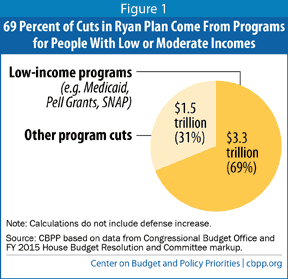

House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan’s new budget cuts $3.3 trillion over ten years (2015-2024) from programs that serve people of limited means. That’s 69 percent of its $4.8 trillion in total non-defense budget cuts.

Not much has changed on this front from Chairman Ryan’s budget plan of a year ago, or the year before that. Then, too, Chairman Ryan proposed very deep cuts, the bulk of which were in programs that serve low- and moderate-income Americans.

The deficit reduction plan that Fiscal Commission co-chairs Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson issued in late 2010 established as a basic principle that deficit reduction should not increase poverty or widen inequality. The Ryan plan charts a radically different course, imposing its most severe cuts on people on the lower rungs of the income ladder.

The Ryan budget proposes $4.8 trillion in non-defense budget cuts through 2024: $900 billion from non-defense discretionary (NDD) programs and $3.9 trillion from entitlements and other mandatory programs. These cuts are in addition to the discretionary and entitlement cuts imposed by the 2011 Budget Control Act’s (BCA) budget caps and sequestration.

Cuts in low-income discretionary and entitlement programs likely account for at least $3.3 trillion — or 69 percent — of the $4.8 trillion in non-defense cuts — and probably more than that. As the box below explains, our assumptions regarding the size of the low-income cuts are quite conservative. The $3.3 trillion figure includes:

By relying disproportionately on cuts to low-income programs, Chairman Ryan’s new budget follows the same pattern as his previous budgets. Measured on a comparable basis, his budget last year would have cut low-income programs by $3.1 trillion over ten years, a figure representing 72 percent of its total cuts.[3] The small differences between those figures and this year’s comparable figures — $3.3 trillion in low-income cuts, representing 69 percent of the total cuts — reflect more a change in baselines and the new ten-year budget window (2015-2024 instead of 2014-2023) than a change in policy priorities.

This analysis finds that roughly $3.3 trillion — or 69 percent — of the ten-year cuts in Chairman Ryan’s budget affect programs that assist low- and moderate-income people. But the cuts may be even more heavily weighted toward low-income people. Why is that?

As noted, the budget includes $250 billion in unspecified mandatory cuts in the Income Security function. We allocated those cuts proportionally among the programs in that function: $150 billion in cuts for low-income programs such as school lunch, Supplemental Security Income, and the Earned Income Tax Credit, and $100 billion in cuts for the remaining programs. Those remaining programs are almost entirely military retirement and state unemployment insurance. If military retirement takes its proportionate share of the unspecified mandatory cuts, it would have to be cut about $48 billion over ten years — eight times the size of the cut in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 that created such a firestorm that it was quickly repealed. If one concludes that military retirement will not be cut, the low-income share of the $250 billion in unspecified mandatory cuts rises towards $200 billion.

It may also be difficult for Congress to cut state unemployment insurance. Now that federal unemployment benefits have expired, essentially only the state unemployment trust funds remain. For these programs, benefits are prescribed by state law and financed by state unemployment taxes (the transactions show up in the federal budget for obscure, technical reasons). If one also concludes that Congress would not force states to cut their own unemployment benefits, eliminating these funds as a potential source of savings, then almost all of the $250 billion in unspecified mandatory cuts in the Income Security category must come from low-income programs.

Finally, the Ryan budget calls for $125 billion in mandatory cuts from the budget category known as Commerce and Housing Credit, which contains the postal service, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, deposit insurance, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and other regulators. Through bank fees, housing loan fees, regulatory fees, and the sale of postage stamps, this budget category runs a small net profit for the government. The Ryan plan would apparently increase that net profit sevenfold, by “eventually eliminating” Fannie and Freddie, “reforming” the postal service, eliminating funding for the Dodd-Frank bank regulators, and possibly requiring banks to pay the FDIC higher annual fees.

But it is hard to see how these proposals could save even half the $125 billion that the Ryan budget assumes. Either there is an unstated plan to charge far more for mortgages and deposit insurance — which we implicitly assume by taking the figures in this budget category at face value — or else about $70 billion of the mandatory cuts located in this function are better viewed as unspecified mandatory cuts to the budget as a whole. If the latter is correct (and if these unspecified cuts are not allocated to Social Security, Medicare, or veterans’ programs), then a proportionate allocation would add another $50 billion in cuts to low-income mandatory programs.

In short, the low-income mandatory cuts could total up to $3.3 trillion over ten years rather than our estimate of almost $3.15 trillion. Combined with the discretionary low-income cuts, the total low-income cuts would then be roughly $3.45 trillion, and the share of all budget cuts affecting programs to assist low- and moderate-income people would rise from 69 percent to 72 percent.

Lastly, it is worth noting that the budget proposals in Chairman Ryan’s plan are calculated starting from current law, in which the American Opportunity Tax Credit expires after 2017, as do the improvements in the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit that were enacted in 2009. Those expirations, which affect low- and moderate-income taxpayers, total another $125 billion over ten years and can be viewed as cuts that are simply built into Chairman Ryan’s base.