The Social Security Disability Insurance (DI) program provides modest but vital benefits to workers who become unable to perform substantial work on account of a serious medical impairment. Although some critics charge that spending for the program is “out of control,” the bulk of the rise in federal disability rolls stems from demographic factors: the aging of the U.S. population, the growth in women’s employment, and Social Security’s rising retirement age. Other factors — including the economic downturn — also have contributed to the program’s growth, but its costs and caseloads are generally in step with past projections.

The Social Security trustees project that the DI trust fund — which is legally separate from the Old Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund for the Social Security retirement and survivors’ programs — will become insolvent in 2016; the Congressional Budget Office concurs. If policymakers take no action to bolster the fund, beneficiaries’ checks will have to be cut by about one-fifth after that. But the fund’s anticipated insolvency should come as no surprise; when policymakers last changed the allocation of taxes between DI and OASI in 1994, they expected the DI fund to run dry in 2016.

Policymakers should address DI’s pending depletion in the context of overall Social Security solvency. Both DI and OASI face fairly similar long-run shortfalls; DI simply requires action sooner. Key features of Social Security — including the tax base, the benefit formula and cost-of-living adjustments, and insured-status requirements — are similar or identical for the two programs, and most DI recipients are near or even over Social Security’s early-retirement age. Tackling DI in isolation would leave policymakers with few — and unduly harsh — options, and lead them to ignore the strong interactions between the disability and retirement programs. A balanced solvency package would also be an opportunity to make sorely needed improvements in the needs-tested Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, which is distinct from Social Security but has important intersections.

If policymakers are unable to agree in time on a sensible solvency package, however, they should reallocate taxes between the retirement and disability funds — a traditional and noncontroversial action that has occurred often in the past.

Changes in the workforce explain most of the growth in the disability rolls. That’s not the impression conveyed, however, by many recent criticisms of the program.[1]

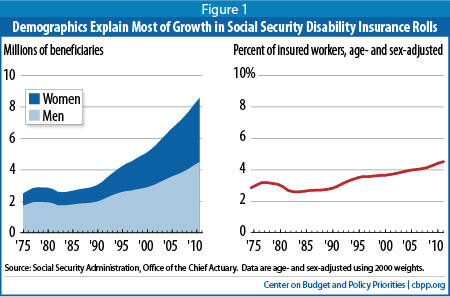

In December 2011, 8.6 million people received disabled-worker benefits from Social Security. Payments also went to some of their family members: 160,000 spouses and 1.9 million children. The number of disabled workers had tripled since 1980, and doubled since 1995 (see Figure 1).

Meanwhile, the “working-age population” — conventionally described as people age 20 through 64 — has grown much less rapidly. It has increased by about 40 percent since 1980, and by less than one-fifth since 1995, leading some critics to note the disparity between the very large percentage growth in the DI rolls and the smaller percentage increase in the number of people in this age range. However, the growth in the number of people receiving DI benefits and the growth in the “working-age population” are not directly comparable. Several important factors have swelled the number of disabled workers substantially during the last few decades:

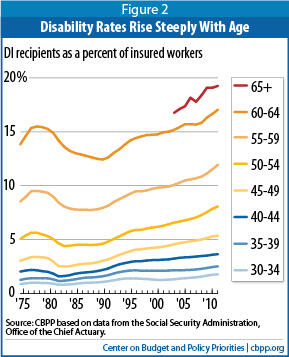

- Baby boomers have aged into their high-disability years. Aging takes a toll on many workers’ bodies and minds long before retirement age. People are roughly twice as likely to be disabled at age 50 as at age 40, and twice as likely to be disabled at age 60 as at age 50. (See Figure 2.) As the baby boomers — the huge cohort of people born between 1946 and 1964 — have grown older, the number of disability cases has risen substantially.

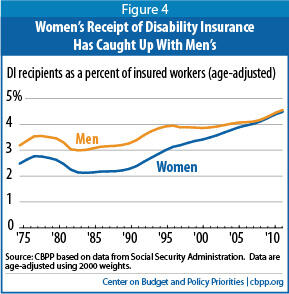

- More women have qualified for disability benefits. In general, workers with severe impairments can get disability benefits only if they have worked for at least one-fourth of their adult life and for five of the last ten years. Until women joined the workforce in significantly greater numbers in the 1970s and 1980s, relatively few women met those tests; as recently as 1990, male disabled workers outnumbered women by nearly 2 to 1. Now that more women have worked long enough to qualify for disability benefits, the ratio has fallen to 1.1 to 1. This has been a large factor behind the increase in the number of DI beneficiaries.

-

Social Security’s full retirement age rose from 65 to 66. When disabled workers reach full retirement age, they begin receiving Social Security retirement benefits rather than disability benefits. The increase in the retirement age has delayed that conversion for many workers. In December 2011, more than 400,000 people between 65 and 66 — nearly 5 percent of all DI beneficiaries — collected disabled-worker benefits; under the rules in place a decade ago, they would have been receiving retirement benefits instead.

The Social Security actuaries express the number of people receiving disability benefits using an “age- and sex-adjusted disability prevalence rate” that controls for these factors. That rate rose from 3.1 percent of the working-age population in 1980 to 3.5 percent in 1995 and 4.5 percent in 2011. (See Figure 1.) Expressed another way, age- and sex-adjusted rates of receipt are 47 percent higher than in 1980 and 30 percent higher than in 1995. That is a significant increase. It is not nearly as dramatic, however, as some alarmists have painted.

Yet rates of receipt have indisputably risen, even when adjusted for age and sex and for the rising retirement age. Why? The reasons are not fully understood, but include:

- Legislative changes. In the early 1980s, the Reagan Administration used its influence over the process of determining eligibility, including new powers to conduct medical reviews granted in a 1980 law, to limit the number of people approved for DI and to terminate benefits for thousands of people already on the rolls. Disability caseloads fell even during a deep economic slump. A backlash ensued from governors, members of Congress, and the courts. Ultimately Congress enacted the Disability Benefits Reform Act of 1984 (DBRA) to clarify eligibility and to limit terminations to cases where the agency could show that the beneficiary’s medical condition had improved. Notably, DBRA required the agency to consider the impact of multiple impairments and to issue new regulations for evaluating mental impairments that “realistically evaluate the ability of a mentally impaired person to engage in [substantial work] in a competitive workplace.”[2] Although some scholars disparage the new rules as “liberal” or “subjective,”[3] they nevertheless reflected Congress’s determination to give fair weight to the full range of medical evidence in complex cases.

An unfortunate tactic of some program critics is to compare today’s receipt rates with those of the early- and mid-1980s. That amounts, however, to cherry-picking the data. Rates of receipt fell to record lows in 1982 through 1984 in the heyday of the Reagan Administration crackdown, and those thus are atypical years for DI receipt. Although some critics apparently want to return to Reagan-era practices, lawmakers convincingly repudiated those practices by enacting DBRA on a bipartisan basis.[4]

- Workplace factors. Work is less physical than in the past, leading some analysts to expect a decrease in the prevalence of disability. But a surprisingly large fraction of jobs — including those performed by older workers — still involves arduous physical demands or difficult working conditions. One study finds that more than one-quarter of jobs performed by workers age 58 to 64 were physically demanding and almost half were either physically demanding or involved difficult working conditions (such as cramped workspace or labor involving exposure to extreme weather conditions, contaminants, hazardous equipment, high levels of noise, or similar conditions).[5] Even sedentary work carries its own set of health hazards, such as obesity.[6]

The accelerating pace of globalization and technological change has been particularly unforgiving to older, less-educated workers and those with cognitive impairments. Whereas in the past such workers — even if they had serious health problems — might have been able to find jobs, the combination of poor health and poor labor market prospects has probably tipped many onto the disability rolls.[7] A trio of researchers who generally argue that the shift to jobs that emphasize “mind over muscle” bodes well for the future employment of older workers nevertheless caution that “[c]ognitively demanding work may be better suited for older people than physically demanding work, but probably not for those with limited education.”[8] Reductions in funding for public and nonprofit organizations that offer sheltered work, and the difficulty faced by the mentally ill in obtaining job accommodations notwithstanding the Americans with Disabilities Act, may have pushed some people who are unable to cope with a competitive, more technological workplace onto the disability rolls.[9]

- Rising cost and declining availability of health insurance. DI beneficiaries qualify for Medicare after a two-year waiting period.[10] With employer-sponsored health insurance eroding and the individual-policy market becoming costlier or outright unavailable, Medicare eligibility may loom larger and larger in some workers’ decisions to apply for DI. Researchers have found evidence that it is a significant factor for some applicants.[11] Other researchers have found that states with stronger health insurance regulations — specifically, those that require “guaranteed issue” (limiting insurers’ ability to deny coverage based on pre-existing conditions) and “community rating” of premiums (limiting insurers’ ability to charge different prices based on individual demographic and health characteristics) — send fewer workers onto the DI rolls. This suggests that implementation of the Affordable Care Act may diminish pressures on the DI program.[12]

- Rising retirement age. Social Security’s rising retirement age has a very simple, direct effect on disability caseloads by delaying the conversion to retirement benefits. It also has an indirect effect by making disability benefits relatively more attractive. Workers may file for reduced retirement benefits as early as age 62. As the full retirement age rises, the magnitude of the reduction in an individual’s monthly Social Security benefit because he or she began drawing benefits at age 62 grows substantially. Disability benefits, the level of which is equivalent to the level of full retirement benefits, have always been more generous than early-retirement benefits for people who began drawing Social Security before the full retirement age, but that wedge has widened and will continue to do so over the coming decade as Social Security’s full retirement age climbs to 67. Some researchers believe this explains significant growth in the DI program, especially over the last decade, although others conclude it has affected applications more than actual receipt.[13]

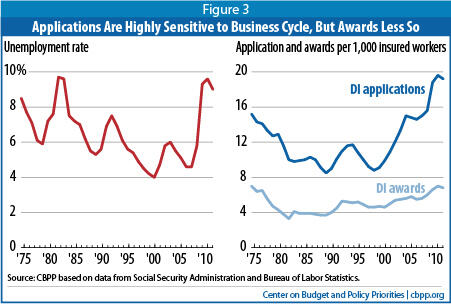

- Economic downturn. Many observers assume that the Great Recession and its aftermath account for rapid growth in the disability rolls. That is buttressed by press stories and academic studies showing that people turn to the disability program when their unemployment benefits expire.[14] Yet economists generally find that while a sour economy significantly boosts applications to the program, it has a much smaller effect on awards (see Figure 3). The implication is that economic downturns tend to attract more marginal, partially disabled applicants to the program, but their applications are more likely to be denied.[15] Therefore, while the economic downturn has surely contributed to the program’s growth, its influence should not be overstated.

One frequently overlooked facet of recent growth in the disability rolls is the fact that women have caught up with men. Although the bulk of the rise in women’s receipt of DI stems from their rising labor force participation, that is not the whole story. Until the mid-1990s, insured women of any age — that is, women who had worked enough to qualify for DI in the event of disability — were only about three-fourths as likely as insured men to receive DI benefits. Now they are equally likely to do so. (See Figure 4.) Because this comparison is limited to insured workers, this change is not simply explained by women’s rising labor force participation. Researchers, who have overwhelmingly focused on how DI has affected males’ labor force participation, have rarely noted this trend and have studied it even less. Whatever the reasons for this trend, it does not seem valid to criticize as a deficiency, or a sign of recent laxness in the program, the growth in DI receipt that is attributable to insured women reaching parity with insured men.

Trends in DI contrast with those in Supplemental Security Income (SSI), a means-tested program also run by the Social Security Administration. SSI pays subsistence benefits to people who are elderly or disabled and have little or no income and assets. It generally brings their incomes up to about three-quarters of the poverty line for individuals and almost 90 percent of the poverty line for couples.

[16] Unlike DI, SSI benefits are not financed by payroll taxes and do not require a past work history.

People with severe disabilities who lack the work history for DI — as well as some who qualify for DI but receive a very small DI benefit — can turn to the SSI program for help to meet their basic needs. Until the recent economic downturn, the number of working-age SSI recipients — that is, recipients age 18-64, who can qualify for SSI only by demonstrating acute financial need and a severe disability — had been stable or declining as a percentage of the U.S. population since the mid-1990s.[17] That trend is almost certainly related to the maturation of the DI program. As more people (especially women) qualify for DI on the basis of their prior work history and receive DI benefits that are sufficient to lift them over SSI’s very low income limits, fewer qualify for SSI — a fact that is often overlooked.

The DI program aids people who, because of a severe medical impairment, can no longer support themselves by working. Its eligibility criteria are stringent:

- Insured status. Applicants for DI benefits must be both fully insured and disability insured. Being fully insured means they must have worked for at least one-fourth of their adult lives. Being disability insured means they must have worked in at least five of the last ten years.[18] The Social Security OASI program also uses the fully insured test but imposes no “recency” test, and many people who are fully insured are not disability insured. Applicants who cannot meet these requirements do not qualify for Social Security. (They may turn to SSI if their income and assets are very low.)

- Severe impairment. Applicants must show that they suffer from a “severe, medically determinable physical or mental impairment that is expected to last 12 months or result in death.” The regulations list acceptable medical sources as licensed physicians or (for certain specific conditions) licensed psychologists, optometrists, speech/language pathologists, or podiatrists.[19] The agency generally gives greater weight to the applicant’s treating physician, but treats that provider’s opinion on the nature and severity of the applicant’s impairment as controlling only when it is well supported by clinical and laboratory diagnostic techniques and is consistent with the other substantial evidence in the case record.[20] Other medical or social service providers — such as nurse practitioners or licensed clinical social workers — do not suffice, nor do statements from the applicant’s family, friends, teachers, or co-workers. The Social Security Administration (SSA) will order and pay for a consultative examination where merited.

- Inability to perform substantial work. Applicants must be unable to perform substantial gainful activity, which is currently defined as an inability to earn $1,010 per month ($1,690 for the blind).[21] That threshold amounts to working less than full-time (about 35 hours a week) at the minimum wage of $7.25, or less than 40 percent of the median earnings of full-time workers with a high school diploma but no college.[22] The law specifically requires that the applicant’s physical or mental impairment must render him not just unable to do his past work, but unable — considering his age, education, and work experience — to do any other kind of work that exists in the national economy, regardless of whether that work exists in his specific geographic area or whether he would be hired if he applied. So-called vocational factors — experience and education — are considered for older applicants with limited skills and education.

- Waiting period. The law requires that the impairment must already have lasted for at least five months before the applicant can qualify for DI. Together with the requirement that the impairment must be expected to last another 12 months or result in death, this emphasizes that DI is not a program for the temporarily disabled. SSI may be available during that period for very poor applicants; sick leave, private insurance, family resources, or savings might tide over others. The waiting period provides an intuitive reason why applications rise during recessions. In a robust economy, few workers will quit a job to subsist on little or nothing for five months with an uncertain prospect of a DI award; but in a recession, a spell of unemployment can last long enough for a disabled worker to be able to satisfy the waiting-period requirement.

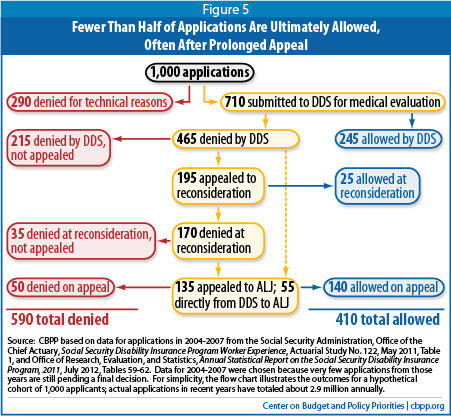

Claimants apply to the SSA, which rejects people who are technically disqualified (chiefly because they lack insured status) and submits the remaining applications to each state’s disability determination service (DDS) for medical evaluation. If denied at the DDS level, the applicant may appeal. Ultimately, of about 1,000 initial applications, about 410 are awarded benefits — more than one-third of them on appeal (see Figure 5).

Typical processing times at the DDS level are three to four months, and processing times at the hearing level average about a year.[23] The allowance rate at the Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) level (also known as the hearing level, generally the second level of appeal) is quite high, which has led to some valid concerns about inconsistency in decisions; yet it is important to remember that ALJs are often seeing claimants whose condition has deteriorated since their application was turned down and whose case file is better documented when it reaches the ALJ (often with the help of an attorney) than it was at the DDS stage.

If accepted, claimants are subject to periodic review to verify that they are still disabled. These continuing disability reviews (CDRs) are, by law, supposed to be conducted at least once every three years unless the beneficiary’s disability has been judged to be permanent. SSA estimates that CDRs result in eventual savings of about $10 in benefits (in Social Security, SSI, Medicare, and Medicaid) for each $1 they cost to conduct.[24] Nevertheless, as discussed below, Congressional cost-cutting efforts have hampered SSA’s ability to conduct these reviews on schedule.

DI recipients receive modest benefits. Benefits are based on the worker’s average earnings from early adulthood until the onset of disability (with up to five years of zero or low earnings dropped).[25] For comparability, earnings in earlier years are indexed to reflect the increase in average wages since the year those earnings were received. For disabled workers as well as retired workers, an individual’s benefit level is computed by applying a progressive formula to past average earnings. The formula leads to larger dollar benefits for higher earners, but the benefits that higher earners receive replace a significantly smaller percentage of their past earnings — a fraction known as the “replacement rate” — than is the case for workers who received lower wages over their careers. (See Table 1.)

Most disabled workers collect benefits only for themselves. In a minority of cases, other family members may also be eligible to collect — most commonly, the minor children of the worker.[26]

The economic circumstances of most disabled workers are modest, and in some cases, even precarious. The average monthly DI benefit in December 2011 was just $1,111 (or $13,326 on an annual basis). Only 6 percent of DI beneficiaries collected more than $2,000 a month.[27] A careful comparison of disabled workers’ benefits to their past earnings found that their benefits replaced about 55 percent to 60 percent of average lifelong earnings for a median worker, and about 50 percent to 55 percent of final earnings prior to the disability.[28] People who receive disability insurance benefits undergo a sharp drop in their standards of living.

Because it is a social-insurance program — not a means-tested program — DI pays benefits to eligible workers based on their medical condition and their past work, without regard to their assets or non-earnings income. Nevertheless, most beneficiaries depend on their DI benefits for their subsistence. Surveys show that DI benefits make up more than 90 percent of income for nearly half of non-institutionalized recipients, and more than 75 percent of income for the vast majority of recipients. Almost one-fourth of DI beneficiaries fall below the poverty line, and the majority live below 200 percent of the poverty line.[29] About 13 percent of disabled-worker beneficiaries also collect SSI, which indicates that they are very poor — SSI lifts them to just over three-fourths of the poverty line — and that they have few or no assets.[30]

Table 1

Past Earnings, Benefit Amounts, and Replacement Rates for Hypothetical Steady Workers Becoming Disabled at Age 50 in 2012 |

| |

Minimum-wage worker |

Low earner

(75 percent of average earnings) |

Average earner |

High earner

(150 percent of average earnings) |

Maximum earner |

| Average indexed monthly earnings (AIME) |

$1,274 |

$2,608 |

$3,477 |

$5,216 |

$8,564 |

Primary insurance amount (PIA), reflecting Social Security’s progressive benefit formula

(benefit amount for worker with no dependents) |

853 |

1,279 |

1,558 |

2,013 |

2,516 |

| Maximum family benefit |

1,083 |

1,919 |

2,336 |

3,020 |

3,773 |

| “Replacement rates” (as a percentage of past earnings) |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Worker only |

67% |

49% |

45% |

39% |

29% |

| |

Family maximum |

85% |

74% |

67% |

58% |

44% |

| Source: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities based on data from Social Security Administration. Dollar figures are monthly amounts. All workers are assumed to have worked steadily between ages 22 and 49 before becoming disabled at age 50; their past earnings are summarized in their Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME). The Primary Insurance Amount (PIA) in 2012 is calculated as 90 percent of AIME up to $767, 32 percent of AIME between $767 and $4,624, and 15 percent of AIME over $4,624. The PIA is the basic benefit amount for a worker with no eligible dependents. The family maximum shown is payable to a worker with one or more eligible dependents — children, or (less commonly) spouse and child(ren). Spouses are eligible for benefits only if they are 62 or older or are caring for the disabled worker’s eligible children. Examples omit the effect of the upcoming December 2012 cost-of-living adjustment. |

Practically since the DI program’s creation, economists and policymakers have debated whether it results in workers leaving the labor market. Evidence suggests, however, that few beneficiaries could earn more than very small amounts if they did not receive DI.

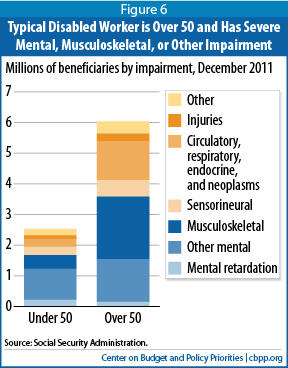

The typical DI beneficiary is in his or her late 50s — 70 percent are over age 50, and 30 percent are 60 or older — and suffers from a severe mental, musculoskeletal, or other debilitating impairment.[31] (See Figure 6.) Nearly one-quarter of beneficiaries lack a high school diploma, and only 10 percent have a four-year college degree.[32] Labor-market prospects for such applicants are poor.

It is important to note that DI beneficiaries are permitted to work. After all, the criterion for eligibility is not complete inability to work, but rather the inability to perform substantial gainful activity (SGA). There is no bar on recipients earning up to the SGA threshold — currently $1,010 per month — while collecting benefits. Recipients may earn

unlimited amounts for a short period without jeopardizing their benefits, while they test their ability to return to work. (See box on page 14 for a summary of work incentives in the DI program.) DI benefits are low, and one would expect beneficiaries to take advantage of these rules by trying to supplement their benefits with earnings if they are able to do so.

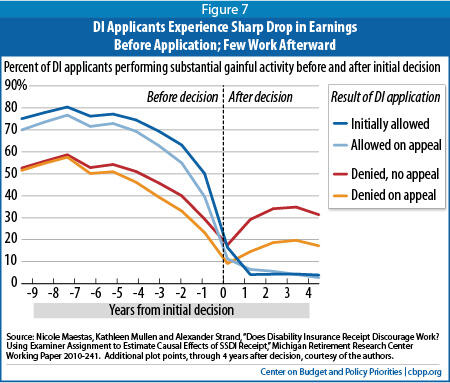

Most beneficiaries, however, do not have earnings. (See Figure 7.) Researchers report that only 12 percent of DI recipients were employed in 2007, when the labor market was still strong. A larger fraction of beneficiaries who were tracked for ten years — 28 percent of them — worked at some point after their DI application was approved, but generally episodically and at low earnings. Only 7 percent had their benefits suspended for even a single month because their earnings exceeded the threshold. Just 4 percent had their benefits terminated because of earnings, and of those, more than one-quarter subsequently returned to the DI rolls. Not surprisingly, beneficiaries who were younger than 40 when they began to receive DI — a distinct minority of beneficiaries — resumed working at higher rates than did older disabled workers.[33]

If beneficiaries could readily work, we might expect a substantial number to make use of the program’s work incentive features to work enough to maximize their earnings without losing DI benefits. Yet there’s scant evidence of such behavior. Very few beneficiaries — 0.2 percent to 0.4 percent, in one study — hold their earnings just under the SGA (a behavior known as “parking”), presumably to avoid triggering benefit suspension and eventual termination. A somewhat larger, but still relatively modest, share of recipients who are converted from DI benefits to Social Security retirement benefits when they reach Social Security’s full retirement age — about 10 percent of them, in one study — return to work after reaching the full retirement age, when all restrictions on their earnings disappear. As that study’s authors emphasize, “The effects we document are large increases in percent terms; however, they do not suggest that all or even most DI beneficiaries can or would work.”

The disability insurance (DI) program has several provisions that are designed to smooth beneficiaries’ return to work.

The law permits DI recipients to earn unlimited amounts for nine months (not necessarily consecutive) — a period known as the trial work period — and in a subsequent three-month grace period before benefits are suspended.

During the next three years — a period known as the extended period of eligibility — those whose benefits have been suspended because of earnings may automatically return to the DI rolls if their earnings sink below the substantial-gainful-activity limit (SGA, currently defined as earnings of $1,010 per month).

If their benefits are formally terminated at the end of that period, former beneficiaries are generally eligible for expedited reinstatement — without serving another five-month waiting period and with streamlined eligibility criteria — for another five years if their earnings fall below the SGA level and their original disability, or a related condition, persists or worsens.

Former beneficiaries who have returned to substantial work may receive Medicare coverage for seven and a half years after their cash benefits stop.

These work incentives are available only to DI recipients who continue to have a severe medical impairment — that is, who have not experienced a medical recovery. Lawmakers have recognized that cutting off benefits and supports abruptly to such vulnerable recipients would discourage them from testing their ability to work. Instead, the time-limited availability of certain cash and health-care benefits is designed to give such beneficiaries a continued safety net at a reasonable cost to taxpayers.

For more information, see Social Security Administration, The Red Book - A Guide to Work Incentives, SSA Publication No. 64-030, January 2012, http://www.ssa.gov/redbook/

Researchers note that even rejected applicants — who are, presumably, less disabled than successful claimants — fare poorly in the labor market, thus illustrating that the program’s eligibility criteria are indeed stringent. The latest and most exhaustive study finds that:

- Barely half of rejected applicants have any earnings. Some 53 percent of rejected male applicants age 45 to 64 (compared with about 20 percent of accepted applicants) had any earnings two years after application, as compared with 82 percent of a control group (selected for its similar demographic characteristics and past work history) of nonapplicants who had earnings.

- Fewer had significant earnings. Two years after application, 43 percent of rejected applicants (compared with about 13 percent of accepted applicants) had earnings equivalent to three months out of the year at the minimum wage. In contrast, 79 percent of nonapplicants had at least that level of earnings.

- For those with earnings, median amounts are quite low. Among rejected applicants who worked, median annual earnings (in 2000 dollars) were only $10,000, just slightly above the poverty threshold, (compared with about $3,500 for accepted applicants). This compared with median earnings of $35,000 among nonapplicants.

The authors found somewhat higher rates of employment among younger applicants: 58 percent of rejected male applicants age 30 to 44 (versus about 19 percent of accepted applicants) had non-negligible earnings two years after application, compared with 85 percent of nonapplicants. Again, however, the amount of earnings for applicants was paltry — the median rejected applicant who worked made just $8,000. Accepted applicants earned far less.

A widely cited recent study provocatively implies that in as many as one-quarter of cases, applicants’ fates might hinge on whether they are assigned to a relatively lenient or extremely tough DDS examiner. It nevertheless concludes that the effects on work and earnings are relatively small. The labor force participation of these beneficiaries would be 21 percentage points higher in the absence of DI, the study estimates, but the beneficiaries’ likelihood of actually securing enough employment to equal or exceed the substantial gainful activity threshold — a steeper hurdle — would be only 13 percentage points higher. The effect on their earnings is, on average, only $1,600 to $2,600 a year.[38]

In short, there is little reason to think that many DI beneficiaries could support themselves by working. The program’s beneficiaries are people who worked in the past, lost their ability to work substantially, and only rarely recover. Its criteria are sufficiently stringent that it rejects many applicants who struggle mightily in the labor market thereafter.

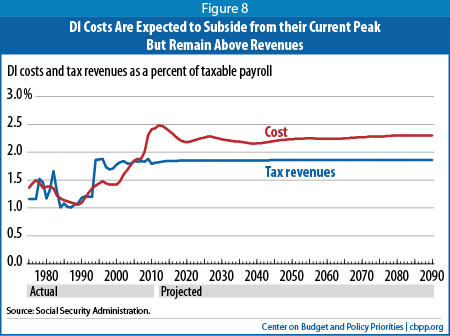

The DI program is financed through a trust fund that receives earmarked revenues — chiefly its statutory share of the Social Security payroll tax and of income taxes collected from higher-income Social Security beneficiaries — and disburses funds for benefit payments and administrative costs. The DI program faces sustained deficits under current policies, although the gap between spending and revenues will shrink from today’s levels with economic recovery and the aging of the baby boomers. (See Figure 8.)

Total scheduled benefits — that is, the amount that would be paid to eligible recipients under the current benefit formula without regard to the trust fund’s status — will fall (as a percentage of taxable payroll) as the earliest boomers reach age 66 and qualify for retirement rather than disability benefits. The first baby boomers, born in 1946, are already reaching that milestone in 2012. Benefits will inch up again in the 2020s as Social Security’s full retirement age rises from 66 to 67, shifting some 66-year-old beneficiaries who otherwise would receive Social Security retirement benefits to disability benefits instead. But by 2031, even the latest baby boomers — born in 1964 — will pass that mark and “age out” of the DI program.

Over the long run, DI and the much larger OASI program face similar funding gaps. For both programs, the 75-year imbalance is about one-fifth of income or one-sixth of costs. (See Table 2.)

Table 2

OASI and DI Face Similar Long-Run Funding Gaps |

| |

Income |

Cost |

Difference |

Shortfall as a percent of... |

| |

Non-interest income |

Starting balance |

Total |

Cost |

Target balance |

Total |

Shortfall |

Income |

Cost |

| OASI |

11.38 |

0.74 |

12.12 |

14.29 |

0.13 |

14.42 |

-2.30 |

-20% |

-16% |

| DI |

1.86 |

0.05 |

1.90 |

2.25 |

0.02 |

2.27 |

-0.37 |

-20% |

-16% |

| Combined |

13.24 |

0.78 |

14.02 |

16.54 |

0.15 |

16.69 |

-2.67 |

-20% |

-16% |

| Source: Social Security Administration, 2012 Trustees’ Report. Cost and income are shown as a percent of taxable payroll over the 2012-2086 period. |

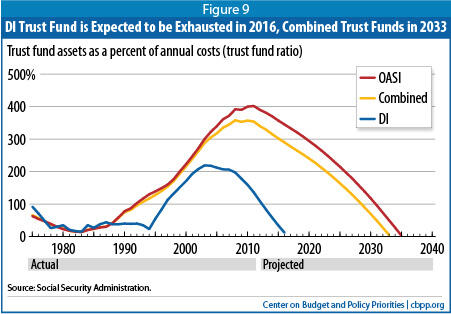

DI insolvency, however, looms much closer. The latest report of the Social Security trustees warned that the DI trust fund will be exhausted in 2016. The separate OASI trust fund would face depletion in 2035. Combined, the two trust funds would run out in 2033.[39] (See Figure 9.)

DI’s projected exhaustion should not come as a surprise. When lawmakers last redirected some payroll tax revenue from OASI to DI in 1994, the program’s actuaries projected that step would keep DI solvent until 2016.[40] Despite fluctuations in the estimates in the time since, the current projection anticipates depletion in 2016.

When the trust funds are depleted, if policymakers took no action, benefits would be cut to whatever level could be covered by incoming tax receipts. In the case of DI, that means benefits would be cut by about 21 percent in 2016, though that percentage would fall slightly in later years as the program’s finances improved. For the combined OASI and DI programs, if policymakers took no action between now and 2033, benefits would be cut by about one-quarter after that date.[41]

Such a sudden and sharp cut in benefits — benefits that recipients depend on for most or all of their income — is unacceptable. Because the DI and OASI programs face similar shortfalls, and because their eligibility criteria and benefit calculations are so closely intertwined, it makes sense to address them together. Lawmakers should take steps reasonably soon to put the entire Social Security program on a sound footing for the long run and divide payroll tax revenues between the two programs as necessary.

Addressing the programs in tandem makes compelling sense:

- More options are available. Many leading options to improve solvency — such as raising the taxable maximum (currently $110,100) or using the “chained CPI” to compute cost-of-living adjustments in Social Security and other programs (as well as to compute the annual adjustments in features of the tax code that are indexed for inflation)[42] — would bolster both the OASI and DI programs. Limiting the menu to options that would affect only DI (other than a straightforward payroll-tax increase) would leave few options, most of which would be draconian.

- Many features are common to both programs. Key features of the OASI and DI programs are similar or identical. The “fully-insured” criterion — which requires earnings in one-fourth of the worker’s adult lifetime — is identical for the two programs (although DI adds a recency-of-work test). The method of computing Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME) is seamless (that is, essentially the same for both programs when scaled for the different lengths of retired workers’ and disabled workers’ careers), and the Primary Insurance Amount (PIA) or basic benefit is calculated from AIME using the same formula. Both programs pay benefits to eligible spouses and children and impose a cap on family benefits, though that family maximum is stricter in DI.

Some proposals to achieve solvency treat these similarities as an afterthought, concentrating on the retirement program and offhandedly stating that the options in question would not apply to the disability program. That is a mistake. For example, a Bipartisan Policy Center panel — in an otherwise carefully crafted plan — recommended a provision to index the PIA formula to life expectancy but stated that the change would not apply to disabled workers until they were converted to retirement benefits. That would mean that benefits would drop abruptly at conversion (i.e., when a disabled beneficiary reaches the full retirement age), which makes little sense and is not desirable.[43] In another example, a leading option to achieve savings would lengthen the averaging period for retirement benefits from an individual’s 35 highest-earnings years to his or her highest 38 or even 40 years, but its drafters stipulate that the change wouldn’t apply to disabled workers.[44] That would widen the wedge between retirement and disability benefits and thereby further encourage applications to the disability program.

Changes in the AIME and PIA calculations are powerful tools for affecting the future level of benefits and should be carefully coordinated across Social Security’s retirement, disability, and survivors’ programs.

- Some Social Security retirement changes would have strong spillover effects onto disability benefits. Another potent tool for achieving savings in Social Security is to increase the retirement age. This option appears in many deficit-reduction plans — for example, in the Bowles-Simpson plan, in proposals advanced in 2008 and 2010 by Congressman Paul Ryan, in illustrative options developed for the National Academy of Sciences, and many others.[45]

Each one-year increase in the full retirement age is roughly equivalent to a 7 percent across-the-board benefit cut for all retirees.[46] That’s true regardless of whether the worker retires early (thereby collecting an even smaller monthly benefit) or continues to work until the new retirement age (thereby collecting the same benefit but for fewer years). Raising the retirement age, however, would not directly affect disabled-worker beneficiaries. In fact, it would — in the absence of other reforms — worsen pressures on the disability program, by widening the gap between disability and early-retirement benefits and by delaying the age at which people receiving DI benefits are converted to Social Security retirement benefits instead.

Table 3

Rising Retirement Age Widens the Wedge Between Disability and Early-Retirement Benefits |

| Year attaining age 62 |

Full retirement age |

% of PIA paid to

age-62 retiree |

% of PIA paid to disabled worker |

| Before 2000 |

65 |

80% |

100% |

| 2000-2005 |

Full retirement age increases by 2 months per year |

100% |

| 2005-2016 |

66 |

75% |

100% |

| 2017-2022 |

Full retirement age increases by 2 months per year |

100% |

| 2022 and beyond |

67 |

70% |

100% |

| PIA=Primary Insurance Amount, the basic amount on which all Social Security benefits are based. Source: Social Security Administration. |

The basic benefit for a disabled worker is 100 percent of PIA — the same benefit paid to a worker who files at his or her full retirement age. That equivalence dates back to the inception of the DI program, when the full retirement age was 65 and there was no early-retirement option for men.[47] The introduction of early retirement for men created a differential, so that being awarded a disability benefit at age 62 was worth 25 percent more than taking an early-retirement benefit. The increase in the full retirement age to 66 increased the benefit differential to 33 percent and thereby modestly increased the incentive to apply for DI benefits; under current law, the wedge will widen to more than 40 percent when the full retirement age rises to 67. (See Table 3.) Options to raise the retirement age further would exacerbate the gap.

Policymakers should take a hard look at the wedge between early-retirement and disability benefits before the retirement age rises to 67 under current law, and they certainly must address the issue if they propose to raise the age further.

- Changes in related programs should be considered. Social Security retirement and disability insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, and SSI serve overlapping populations. A balanced solvency package would consider those interactions and make selected changes to non-Social Security programs, as appropriate.

Most obviously, Social Security solvency legislation would provide an opportunity to make sorely needed changes to the SSI program. Possible reforms include raising the basic SSI benefit (now equal to only about three-quarters of the poverty line), raising SSI’s outdated asset limit (which hasn’t been adjusted for inflation in more than 20 years and disqualifies individuals with over $2,000 in countable assets), reforming SSI provisions that penalize and inhibit retirement savings, and modernizing the SSI rules on how other income — chiefly Social Security benefits — affects an individual’s eligibility for, and benefit level under, SSI. In fact, because three-fifths of elderly SSI recipients and about one-third of disabled adult SSI recipients also receive Social Security, reforming the interaction between the two programs would be a powerful way to boost poor Social Security beneficiaries’ incomes (or at least to soften their income losses from reductions such as an increase in Social Security’s retirement age) in an efficient and effective manner.[48]

Policymakers should also consider lowering the threshold for SSI old-age benefits from age 65 to 62, the Social Security early-retirement age (the age at which people can begin drawing Social Security retirement benefits, at a reduced benefit level) or even 60 (given the severe poverty experienced by a small but not insignificant number of people with limited skills who encounter serious difficulty finding employment at that age). The need to do so will be even greater if policymakers raise Social Security’s full retirement age above 67 (or raise Social Security’s early retirement age above 62). The higher that Social Security’s full retirement age is raised, the greater the benefit reduction percentage that will be applied to people who begin drawing benefits at 62.

For people who have serious health problems that aren’t severe enough for them to qualify for SSI disability or DI benefits but that prevent them from securing much employment in their early 60s — as well as for people in that age range whose skill deficits or cognitive limitations make it very difficult for them to find employment — the increased reduction in Social Security benefits at age 62 as the program’s full retirement age rises may consign them to deep poverty. [49] Setting the SSI eligibility age at 62 or even 60 would help address that problem. Strengthening SSI in this manner also would lessen pressures to try to compensate by expanding certain Social Security benefits, a less-than-optimal approach because Social Security benefits aren’t needs-tested and are hard to target efficiently and effectively on beneficiaries who are impoverished.

Several researchers have published proposals for wholesale reform of the DI program. (See “Proposals to Fundamentally Change DI and Related Programs,” page 22.) Regardless of the pros and cons of such proposals, the eventual budgetary effects of many of them (as well as their effects on vulnerable beneficiaries) are highly uncertain. Moreover, such ambitious changes cannot be adopted and fully implemented before DI insolvency occurs in 2016. At most, policymakers who are crafting legislation to avert insolvency should include carefully designed pilot projects to test such far-reaching plans first, with protection for program participants and a requirement for rigorous evaluation.

Because Social Security benefits are so modest and make up the principal source of income for most recipients, legislators should use tax increases to generate at least half of the savings in an overall solvency package. Those could come from raising the maximum amount of wages subject to the payroll tax (which now encompasses only about 83 percent of covered earnings, well short of the 90 percent figure envisioned by Congress in the 1977 Social Security amendments); broadening the tax base by subjecting voluntary salary-reduction plans, such as cafeteria plans and health-care Flexible Spending Accounts, to the payroll tax (just as 401(k) plans and similar retirement accounts are subject to it); and raising the payroll tax rate. Future workers are expected to be more prosperous than today’s. Under the trustees’ assumptions, the average worker will be 50 percent better off — in real terms — in 2040 than in 2012, and twice as well off by 2070. It is appropriate to devote a small portion of those gains to the payroll tax, while still leaving future workers with much higher take-home pay. Social Security is a popular program, and poll respondents consistently express a willingness to support it through taxes.[50]

If policymakers are unable to agree on a well-rounded solvency package before DI faces depletion, they should — as a stopgap — reallocate payroll taxes between the two programs. As then-Congressman Jake Pickle stated in 1980 during consideration of legislation to reallocate payroll taxes between Social Security’s two programs, “[T]he bill we bring today is a deliberate step both to [ensure] the stability of the trust funds and to provide the Congress the time it will need to make any further changes necessary….Reallocation, the mechanism used in [H.R.] 7670, has been the traditional way of redistributing the OASDI tax rates when there have been changes in the law and in the experience of programs and in order to keep all the programs on a more or less even reserve ratio.”[51]

Several researchers have proposed far-reaching changes in Disability Insurance and related programs:

Tighten standards and adopt experience-rating. Richard Burkhauser and Mary Daly advocate a “work-first” strategy that would emphasize rehabilitation and other services upon DI application, prior to award. They also suggest tightening the adjudication process; restricting eligibility (especially for mental and musculoskeletal impairments); and applying “experience rating” to the payroll tax (that is, levying higher taxes on employers whose former employees qualify for DI at above-average rates, in the hope that this would lead employers to retain and accommodate workers with disabilities). Burkhauser and Daly would also make radical changes in the SSI program, converting it to a block grant.

Expand private disability insurance. David Autor and Mark Duggan advocate expanding private disability insurance (PDI) to cover all employees. Employers would be mandated to enroll their employees and to pay the premiums; firms could collect up to 40 percent of the premiums from their workers. PDI benefits would be paid to workers for two years, starting with the third month after the onset of a disability, and would equal 60 percent of the worker’s past wages. Only when PDI expired could workers apply for DI. (An exception would be made for impairments on SSA’s “Compassionate Allowances” list.) Unemployed workers could buy coverage from their previous employer or go into a pool that is financed by a surcharge on insurance companies and that offers less generous benefits. The authors hope that mandatory PDI would lead employers to retain and accommodate workers with disabilities.

Replace DI for younger workers with a capped benefits package. David Mann and David Stapleton would maintain the current DI and Medicare package only for severely disabled workers 50 or older. All others would receive a “customized” package of benefits determined by a new state-run Disability Support Administration. Those benefits might include cash payments, tax credits to supplement earnings, employment services, accommodations, and equipment. Total federal funding to states to provide these benefits would be capped, with states’ allocations determined by a formula.

Crucial details of these proposals remain unspecified. All would remove important elements of the safety net for people with disabilities by limiting access to DI and SSI or by block-granting part or all of current programs. Block grants pose the risk that states could cut the programs’ already low eligibility limits and benefit levels and place poor people with serious disabilities on waiting lists if a state’s block grant allocation is insufficient to serve all eligible people who apply. The two proposals that emphasize employer responsibility assume that firms would respond by rehabilitating and accommodating workers with serious impairments; but these proposals also raise significant risk of discrimination against people with potentially work-limiting conditions in hiring (and firing), especially among small firms that could not afford the extra costs associated with even a few disability claims.

Although an informed debate about disability policy is healthy, policymakers should not radically change DI and related programs without careful consideration, including analysis of such reforms’ merits and weaknesses, their success or failure elsewhere, and small-scale demonstrations accompanied by adequate protections for participants and rigorous evaluation. At best, evidence about these policies’ effects might trickle in within ten years or so — long after Congress must wrestle with DI’s pending insolvency.

Richard V. Burkhauser and Mary C. Daly, The Declining Work and Welfare of People with Disabilities, AEI Press, 2011; David H. Autor and Mark Duggan, “Supporting Work: A Proposal for Modernizing the U.S. Disability Insurance System,” Center for American Progress and Brookings Institution, December 2010; David Mann and David Stapleton, “A Roadmap to a 21st Century Disability Policy,” Mathematica Policy Research, Center for Studying Disability Policy Issue Brief 12-01, January 2012.

Congress has reallocated payroll tax revenues (by modifying the relative payroll tax rates dedicated to each of Social Security’s two programs) on at least six occasions in the past, and in both directions, demonstrating that this is a traditional and uncontroversial step.[52] The Social Security actuaries estimate that temporarily raising the DI share (currently 1.8 percentage points) of the 12.4 percent Social Security payroll tax by 0.8 percentage points in 2013 and 2014, and then by amounts that gradually shrink to just 0.2 percentage points in 2021-2029, would enable both of the Social Security trust funds to pay scheduled benefits through 2033 — their combined exhaustion date.[53]

DI, OASI, and SSI are entitlement programs — which means they pay the amounts specified in law to people who meet the eligibility requirements and apply for benefits, rather than being controlled by annual appropriations — but their administrative funding is not. Appropriations for SSA’s operations (including the tasks performed for SSA by the state disability determination services) are part of discretionary spending, a category that faces a tight squeeze in the years ahead. SSA’s administrative funding has been frozen since 2010, despite growing caseloads in all three of its programs (OASI, DI, and SSI).[54] Moreover, the Budget Control Act of 2011 adopted aggregate caps on discretionary spending that will cut non-defense discretionary programs by 16 percent, in real terms, by 2021.[55] Over that period, the actuaries estimate that Social Security’s caseloads will grow by 30 percent, and SSI’s by 12 percent. And that’s before the threatened cuts from sequestration.[56]

SSA needs adequate funding to perform its jobs. Those include not just processing applications and administering payments, but carrying out crucial program integrity activities. The Budget Control Act included a special “cap adjustment” for such activities. These cap adjustments set aside a limited amount of money that Congress can use solely to increase SSA funding for program integrity purposes, which include continuing disability reviews (CDRs) and SSI redeterminations of financial eligibility. These limited funding increases do not require offsetting reductions in other non-defense appropriations; in effect, such increases are outside the statutory caps on annual non-defense appropriations that the Budget Control Act established.

As noted previously, CDRs are estimated to reduce eventual benefit payments by $10 for every $1 in increased administrative funding, by removing from the rolls people who are no longer eligible. Such funding therefore helps the budget as well as insuring greater program integrity. Congress nevertheless failed to take full advantage of the allowable cap increases adjustment in the 2012 appropriation, leaving $140 million in SSA administrative funding on the table — and thereby increasing future deficits by more than $1 billion. President Obama has asked Congress to enact the full amount allowed for program-integrity activities in 2013.

In the rare cases where fraud is suspected on the part of applicants or beneficiaries, that allegation triggers a Cooperative Disability Investigation (CDI), a team effort led by SSA’s Office of Inspector General and involving employees from the state DDSs, SSA, and local law enforcement. There are 25 CDI units in 22 states; but here, too, to be widely effective, the effort requires a stable and adequate source of funding.[57]

When lawmakers last redirected some payroll tax revenue from OASI to DI in 1994, they expected that step would keep DI solvent until 2016. Despite fluctuations in the trustees’ projections in the meantime, the current projection anticipates depletion consistent with that projection — in 2016. DI’s trust-fund exhaustion thus comes as no surprise and should not be considered evidence that the program is out of control. While researchers cannot fully dissect all of the reasons for the program’s growth, it’s clear that the bulk of it comes from demographic factors, women’s entry into the labor force in large numbers, and the increase in the Social Security retirement age, and that the DI program’s growth will taper off in the next decade.

DI is an integral part of the Social Security program, and legislators should address it in the context of overall Social Security solvency. The common features and interactions of DI and OASI would make efforts to fix the two programs separately a mistake.

Because Social Security’s finances are fairly predictable, it is not difficult to craft revenue and benefit proposals that would place the program on a sound long-term footing. The best proposals would protect vulnerable workers and beneficiaries and give all participants ample warning of future changes to this vital program. That will enable them to plan their work, savings, and retirement with confidence — while continuing to count on Social Security’s protection in the event of early death or disability.

If policymakers are unable to agree on a well-rounded solvency package before DI faces depletion, they should reallocate taxes between the two programs as a stopgap, as they have done multiple times in the past, while intensifying efforts to develop a long-term solvency package that restores the program’s financial health for decades to come.