- Home

- Many States Cutting TANF Benefits Harshl...

Many States Cutting TANF Benefits Harshly Despite High Unemployment and Unprecedented Need

In 2011, states implemented some of the harshest cuts in recent history for many of the nation's most vulnerable families with children who are receiving assistance through the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant. The cuts affect 700,000 low-income families that include 1.3 million children; these families represent over one-third of all low-income families receiving TANF nationwide.

A number of states have cut cash assistance deeply for families that already live far below the poverty line, ended it entirely for many other families with physical or mental health issues or other challenges, or cut child care or other work-related assistance that make it harder for many poor parents fortunate enough to have jobs to keep them.

Among the state TANF cuts to date:

- At least five states — California, Washington, South Carolina, Wisconsin, and New Mexico — and the District of Columbia have cut monthly cash assistance benefits for TANF families, reducing already very low benefits. In South Carolina, for example, TANF benefits are now just 14 percent of the poverty line for a family of three. These cuts are pushing hundreds of thousands of families and children below — or further below — half of the poverty line.

- States have shortened or otherwise tightened their lifetime time limits on receiving TANF benefits, cutting off aid entirely for thousands of very poor families and reducing benefits for thousands more. California and Arizona shortened their time limits, and several other states tightened time limits.

- States have cut TANF-funded support for low-income working families. Michigan slashed its refundable Earned Income Tax Credit (which is partially funded with TANF funds) by two-thirds, raising state income taxes for several hundred thousand low-income working families and pushing more children and families into poverty. Several other states have weakened "make-work-pay" policies by cutting or eliminating the modest TANF benefits that working-poor families can receive as supplements to their low wages.

Many of the cuts run counter to states' longstanding approaches to welfare reform. For example, some states that had provided support to poor parents working in low-wage jobs have abandoned those policies. Similarly, states have shortened their time limits and eliminated some bases for extensions or exemptions, and applied these changes retroactively. As a result, states have terminated or reduced benefits for some of the most vulnerable families, most of whom have very poor labor market prospects.

These TANF cuts come at a time when unemployment remains very high and the prospects of finding jobs, especially for people with low skills, are poor. In August 2011, unemployment was 9.1 percent. . Over two-fifths (42.9 percent) of the 14.0 million people who are unemployed — 6.0 million people — have been looking for work for half a year or longer, a level of long-term unemployment that remains at levels not seen in the past 60 years. [1]

Despite these economic conditions, states are implementing policies that are shrinking the already low number of poor families with children that TANF serves. In 1994-1995, just before TANF's creation, the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program (AFDC, TANF's predecessor) served 75 families with children for every 100 families with children who lived in poverty. In 2008-2009, TANF served only 28 families for every 100 in poverty. This ratio varies among states; in seven states in 2008-2009, TANF served fewer than 10 families for every 100 in poverty. [2]

To be effective, a safety net must be able to expand when the need for assistance rises and to contract when need declines. The TANF block grant is failing this test, for several reasons: Congress has level-funded TANF since its creation, with no adjustment for inflation or other factors over the past 15 years; federal funding no longer increases when the economy weakens and poverty climbs; and states — facing serious budget shortfalls — have shifted TANF funds to other purposes and cut the TANF matching funds they provide. The next section examines these and related factors.

Why States Are Making Deep TANF Cuts Now

The current fiscal year (fiscal year 2012) is shaping up as one of states' most difficult budget years on record. Some 44 states and the District of Columbia projected budget shortfalls totaling $112 billion for 2012.[3] States have responded to these fiscal pressures by making deep cuts in many education and human service programs, including TANF. [4]

The TANF cuts are due in substantial part to the inadequacy of the federal TANF block grant. Under TANF, federal block grant funding does not rise when caseloads increase in hard economic times. This is a sharp change from the structure of the AFDC program, under which the federal government shared the costs of increased caseloads with the states in order to protect them from the full economic costs of serving more families when the economy weakened.

Furthermore, as noted, the block grant has been level-funded since its creation in 1996, with no adjustment for inflation or any other factor. The same is true for the required levels of state spending (called maintenance-of-effort or MOE spending). At only 72 percent of their original value in inflation-adjusted dollars, state and federal TANF funds can no longer fund the same level of services and support as they did 15 years ago.

States also shifted both federal and state TANF funds previously used to fund cash assistance and related services for poor families to cover the costs of various other programs and services (such as child care, child welfare, homeless assistance, and teen pregnancy prevention programs), enabling states to scale back the state funding devoted to those programs. In fiscal year 2007, before the onset of the recession, states used just 30 percent of their federal and state TANF funds to provide basic assistance to families with children. When the economy slumped badly and TANF caseloads began rising, state TANF agencies were unable to reclaim the transferred funds to cover the costs of providing assistance to the growing number of families in need.

An additional problem is that the federal TANF Contingency Fund — created to provide additional assistance to states during economic downturns — has proven severely inadequate. The original fund was entirely exhausted in December 2010, and the additional money that Congress allocated for fiscal year 2011 was so small that it provided funding for only a few additional months. Funding for 2012 is also likely to last only a few months. [5]

The TANF Emergency Fund, created as a part of the 2009 Recovery Act, provided states with extra help for fiscal years 2009 and 2010, but that fund ended on September 30, 2010 when Congress declined to extend it. With no additional federal funds to draw upon, states ended countercyclical employment programs that they had created to help low-income parents and youth find jobs in a period of high unemployment and began cutting TANF benefits and services.

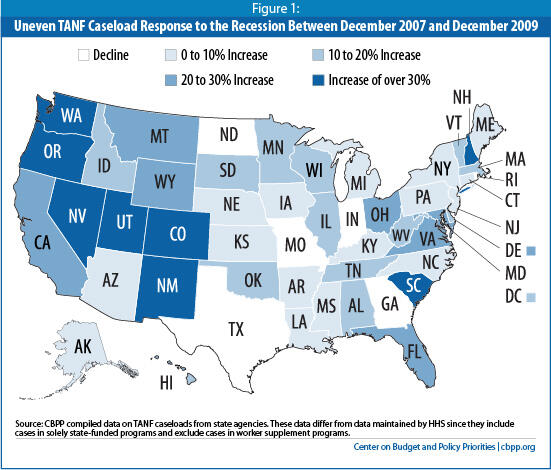

As a result of all of these factors, changes in TANF caseloads stemming from the recent recession have varied significantly across the states. Although the national caseload increased by just 13 percent, caseloads in 22 states showed little or no increase, whereas caseloads increased by more than 20 percent in 15 states and by between 11 and 20 percent in 13 states (see Figure 1).[6] It is the states with the most responsive caseloads that have faced the most difficult budget choices, as they are assisting many more families with no additional money to help cover the extra costs. In many cases, these are the same states whose economies have been hit hardest by the recession — and that are now making some of the most severe TANF cuts.

The rest of this paper describes the kinds of TANF cuts states have made in 2011.

Benefit Reductions

Some states have reduced TANF benefits even though benefits were already very low. In July 2010, TANF benefits for a family of three were less than half of the poverty line in all states and below 30 percent of the poverty line in over half of the states. [7] The median benefit for a family of three was $429 a month, just 28 percent of the poverty line; adding in food stamp benefits in the median state got a family up to 68 percent of the poverty line. As of July 2010, the maximum TANF benefits in 30 states had declined by more than 20 percent in real dollars since TANF was created in 1996.

Several states have cut benefit levels. For example:

- Washington cut TANF benefits by 15 percent effective February 1, 2011, reducing benefits for a family of three that has no other income by $84 per month, from $562 to $478.

- South Carolina cut TANF benefits by 20 percent effective February 1, 2011, reducing benefits for a family of three from $270 per month to $216 — just 14 percent of the poverty line.

- New Mexico cut TANF benefits by 15 percent effective January 1, 2011, reducing benefits for a family of three by $67 a month, from $447 to $380.

- California cut TANF benefits by 8 percent effective July 1, 2011, reducing benefits for a family of three from $694 to $638.

- Wisconsin reduced benefit levels by $20 for many TANF recipients effective October 1, 2011. Benefits were reduced from $673 to $653 for those participating in community service and from $628 to $608 for those participating in transitional placements.

- The District of Columbia cut benefits by 20 percent effective April 1, 2011 for families that have received assistance for 60 months or longer. A family of three subject to the decrease will see its benefit cut from $428 to $342. These reductions for families beyond 60 months are slated to increase over time, with the cut increasing to 25 percent for 2013, to 41.7 percent for 2014, and to 100 percent (i.e., benefits will be eliminated) for 2015 and beyond.

Finally, New Hampshire eliminated its Unemployed Parent Program for two-parent families.

These benefit reductions, which will affect hundreds of thousands of families, can have longstanding consequences for the children in these families. A recent examination of the scientific evidence by Greg J. Duncan and Katherine Magnuson, economists highly regarded for their work on the impact of poverty on children, has found compelling evidence that lower levels of income cause poor educational outcomes in young children. [8]

Shorter and More Restrictive Time Limits

A number of states have changed their TANF time limit policies. Changes include shortening the time limit, restricting exemptions from the time limit or bases for extensions, taking harsher actions when a family reaches the time limit, and reducing benefits for families that have received aid for certain periods of time even when they are not otherwise subject to time limits.

These were not policy-based changes; rather, they reflect state fiscal pressures. Many of the states that cut benefits or eligibility based on length of TANF receipt previously chose not to take harsh actions against certain groups of families that receive benefits for longer periods of time because they recognized that as caseloads have fallen, many of the families left behind face significant personal and family challenges (including serious mental and physical health issues) that limit their ability to find work.

State actions related to TANF time limits include:

- Arizona reduced its TANF time limit to 24 months, one of the shortest in the country. This change ended benefits for 3,500 low-income families when it was implemented in July 2011; additional families will lose benefits each subsequent month as they reach the 24-month limit. Last year Arizona shortened its time limit from 60 months to 36 months and eliminated the time limit exemption for child-only cases, retroactively subjecting them to the 36-month limit. Arizona's TANF caseload dropped by half over the last year.

- In February 2011, Washington cut off over 5,000 families that had reached 60 months on TANF by narrowing its extension policies. Washington also extended time limits to child-only cases living with ineligible parents (for example, ineligible immigrants).

- California shortened the TANF time limit for adults from 60 to 48 months effective July 1, 2011. For a household of three with one parent, this new limit will result in a reduction of $122 per month in TANF benefits when the parent is removed from the grant after the 48th month.

- Maine, which effectively had no time limit so long as families were participating in work-related activities, adopted a 60-month time limit.

- Michigan tightened its 48-month time limit by eliminating certain bases for exemptions or extensions, resulting in termination of benefits to over 12,000 families in October 2011.

The TANF block grant has been in place long enough for us to know that families who reach time limits are among the most vulnerable families. They are far more likely than other TANF recipients to face employment barriers such as physical and mental health problems and to have lower levels of education that significantly reduce their chances of finding jobs.[9] There is no sound policy argument for shortening time limits when the labor market is so weak — especially since TANF recipients remain subject to stringent work requirements and have their benefits reduced or eliminated if they do not meet those requirements.

Cuts in TANF-Funded Support for Low-Income Working Families

A number of states have reduced the supplemental income their TANF programs provide to families in low-wage jobs, restricted access to important supports that enable many parents to work in low-wage jobs (such as child care and transportation assistance), or otherwise reduced TANF-funded support for working-poor families.

- Weakening "make-work-pay" policies that disregard a portion of earnings. One of the hallmarks of state policies under TANF (as compared to AFDC) was that nearly all states increased the amount of earnings they disregarded when determining working TANF recipients' benefit levels. This year marks the first time since 1996 that states have begun to cut back on these "make-work-pay" policies; here, too, the cuts are solely for fiscal reasons and run counter to the states' own welfare reform approaches and philosophies. California reduced the amount of earnings disregarded each month from $225 plus 50 percent of the remainder to $112 plus 50 percent of the remainder. Reducing the amount of earnings disregarded results in lower TANF benefits for working-poor families. It also means that TANF recipients who obtain jobs lose their TANF eligibility sooner and at lower earnings levels.

- Eliminating or weakening work supplements for families that have left cash assistance for work. In the last few years, a number of states have begun providing a transitional benefit to families that leave welfare for low-wage work. Despite the success of these programs, some states are suspending or terminating them, or reducing the monthly benefit amounts, in order to cut costs. Washington and New Mexico have suspended their programs. In 2010, Delaware ended its program and Massachusetts suspended a similar program that provided supplemental aid to working families on SNAP (food stamps).

- Eliminating or reducing state EITCs, which provide work incentives and support for working families. Several states cut back on state Earned Income Tax Credits. Michigan reduced its refundable EITC to 6 percent of the federal credit (down from 20 percent) effective in 2012, which is expected to raise state taxes on hundreds of thousands of low-income working families and push 9,000 more children and their families into poverty. Wisconsin lawmakers filled $56 million of the state's budget shortfall by scaling back the state's Earned Income Tax Credit for 152,000 low-income working families, at an average cost of $518 for families with three or more children and $154 for families with two children, annually.

- Reducing child care assistance. States are also weakening other supports for families leaving TANF for work. For example, South Carolina has shortened the period for which employed former TANF recipients can receive transitional child care subsidies from 24 to 12 months after their cash assistance ends. Arizona, which already cut the number of children receiving child care assistance from 48,000 to 29,000 since February 2009, has reduced state funding for child care subsidies again this year, terminating child care subsidies for another 13,300 children.

Some states have also reduced the resources for their work programs. They are providing less assistance to help individuals find jobs, and case-workers, carrying bigger caseloads, are providing less employment assistance at a time when more is needed.

To be sure, hard trade-offs are necessary when funding is tight and need is high, and temporary cuts in work programs or work supports may be less harmful than deep cuts in basic assistance that shrink already-low benefits or end eligibility entirely for especially vulnerable families with children. But too often, the core welfare reform areas — basic assistance, child care, and work activities — are the target areas for cuts and are competing against each other in a fixed funding pot. Other programs funded with TANF dollars often are dispersed throughout the state budget and don't necessarily face the same fiscal pressures as the core TANF activities.

Conclusion

The measures outlined above will carry a heavy human cost. Cuts in cash assistance benefits will leave families who are already far below the poverty line with even fewer resources to make ends meet. New time-limit restrictions will eliminate assistance entirely for many families with physical or mental health issues or other challenges that limit their ability to work. Cuts in child care and other benefits that help offset work-related costs will make it harder for the parents lucky enough to have jobs in this economy to keep them. As a result, for the foreseeable future, hundreds of thousands of poor parents and children will face even greater difficulties in meeting their basic needs.

A strong economy contributed to the success of welfare reform in the late 1990s; now, a weak economy has wiped out most of those gains. To be effective, a safety net needs to be able to expand when the need for assistance increases and to contract when the need for assistance declines. The TANF block grant is failing this test.

Governors are Proposing Further Deep Cuts in Services, Likely Harming Their Economies

End Notes

[1] Chad Stone, "Statement on the August Employment Report," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 2, 2011.

[2] LaDonna Pavetti, Danilo Trisi, and Liz Schott, "TANF Responded Unevenly to Increase in Need During Downturn: State-By-State Fact Sheets," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 25, 2011.

[3] Elizabeth McNichol, Phil Oliff and Nicholas Johnson, "States Continue to Feel Recession's Impact," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 9, 2011.

[4] Michael Leachman, Erica Williams, and Nicholas Johnson, "Governors are Proposing Further Deep Cuts in Services, Likely Harming Their Economies," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities," March 21, 2011.

[5] Making these problems worse, owing to a flawed design, the states with the greatest need for additional resources did not all qualify for the contingency funds even when funds were available.

[6] LaDonna Pavetti, Danilo Trisi, and Liz Schott, "TANF Responded Unevenly to Increase in Need During Downturn," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 25, 2011.

[7] Liz Schott and Ife Finch, "https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/10-14-10tanf.pdf," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 14, 2010.

[8] Greg Duncan and Katherine Magnuson, "The Long Reach of Early Childhood Poverty," Pathways, Winter 2011, www.stanford.edu/group/scspi/_media/pdf/pathways/winter_2011/PathwaysWinter11_Duncan.pdf .

[9] LaDonna Pavetti and Jacqueline Kauff, When Five Years Is Not Enough: Identifying and Addressing the Needs of Families Nearing the TANF Time Limit in Ramsey County, Minnesota, Washington, D.C.: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., 2006.

More from the Authors