off the charts

POLICY INSIGHT

BEYOND THE NUMBERS

BEYOND THE NUMBERS

In their poverty plan, House Speaker Paul Ryan and his Republican colleagues placed great stock in the ability of work requirements to reduce poverty. But, as we’ve explained, an array of rigorous evaluations show that work requirements don’t do that. Instead, the research shows:

- Employment increases among cash assistance recipients subject to work requirements were modest and faded over time. Employment among recipients subject to work requirements rose significantly in the first two years of programs that mandated participation in work-related activities but, by the fifth year, the difference in employment rates between those who faced work requirements and those who didn’t had faded. Over five years, at least three-quarters of recipients worked, regardless of whether they faced work requirements.

- Stable employment among recipients subject to work requirements proved the exception, not the norm. The share of recipients subject to work requirements who worked stably — i.e., in 75 percent of the quarters in years three through five — was small, ranging from 22.1 to 40.8 percent.

- Most recipients with significant barriers to employment never found work even after participating in work programs that were otherwise deemed successful. Even with special services that successfully increased employment for individuals facing significant employment barriers, most program participants didn’t find work. For example, a rigorous study of one such program in New York City found that just 34 percent of recipients who participated in the program ever worked over a two-year period.

- Over the long term, the most successful programs supported efforts to boost the education and skills of those subject to work requirements, rather than simply requiring them to search for work or find a job. The two most successful welfare-to-work programs, in Portland, Oregon, and Riverside, California, are often characterized as “work first” programs that required individuals to find jobs quickly, but both supported participation in education or training for some participants. For example, the Portland program, which had the most significant long-term impacts on earnings, initially assigned some participants to short-term training programs and encouraged them to hold out for better-paying jobs.

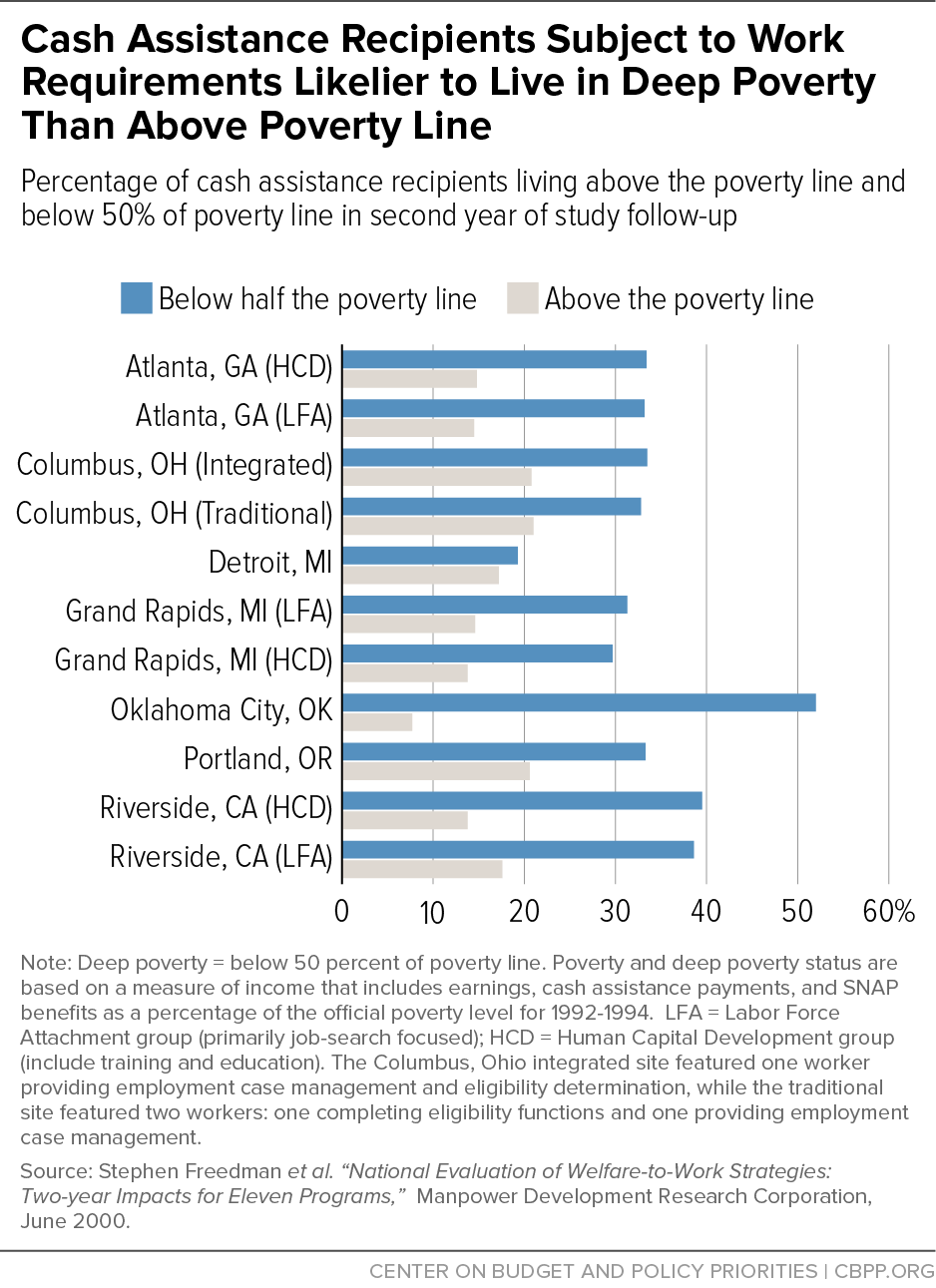

- Most recipients subject to work requirements stayed poor, and some became poorer. Although recipients were likelier to be employed within two years of facing work requirements, their earnings weren’t enough to lift them out of poverty — and in some programs, the share of families living in deep poverty rose. Only two programs of the 13 studied significantly reduced the share of families living in poverty, and in all of them, recipients facing work requirements were likelier to live in deep poverty than above the poverty line (see chart).

- Voluntary employment programs can significantly boost employment without the negative impacts of ending basic assistance for individuals who can’t meet mandatory work requirements. The primary downside of imposing work requirements on public benefit recipients is the harm they can cause to the individuals — and their families — who can’t comply and lose essential assistance as a result. The results from a rigorous evaluation of the Jobs-Plus demonstration, an employment program for public housing residents, suggest that voluntary work programs can be successful without the harmful consequences that typically accompany work requirements.

Topics:

Stay up to date

Receive the latest news and reports from the Center