BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Two new publications synthesize the growing body of high-quality research findings on SNAP’s positive impacts on health and well-being, and they provide important new insight on an issue that’s received relatively little attention: SNAP (formerly food stamp) monthly benefits, which average about $1.40 per person per meal, are too low to help many families buy adequate food through the month.

The publications — a report from the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) and a book (SNAP Matters) from leading researchers — highlight SNAP’s essential role in helping families buy food and its powerful long-term benefits for children. (We’ll discuss those findings in follow-up posts.) The CEA report also summarizes research showing that many SNAP households run out of benefits towards the end of the month, suggesting benefits are too low to ensure that some families have adequate food. SNAP participants generally receive benefits in one monthly installment, and participants spend close to 80 percent of benefits within two weeks of receipt, research suggests.

The CEA report cites an Institute of Medicine report showing that the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) “Thrifty Food Plan,” the basis for SNAP benefits, is based on unrealistic assumptions about the cost that families face to buy a range of nutritious foods and their available time to shop for and prepare food. Also, the benefit formula doesn’t fully account for geographic differences in food prices.

The CEA report compiles research showing how running out of benefits may affect low-income families. Some studies that it cited suggest SNAP participants’ caloric intake falls 10-25 percent over the course of the month, for example.

Also, a study found that the rate of hospital admissions for low blood sugar (which can occur when diabetics reduce their food intake) among low-income individuals in California was 27 percent higher in the last week of the month compared to the first, an increase not found among higher-income individuals — suggesting that exhausting food budgets contributes to these hospitalizations. (California distributes SNAP in the first days of the month.) Similarly, emerging research shows that children in SNAP families have higher test scores and fewer disciplinary incidents earlier in the benefit cycle.

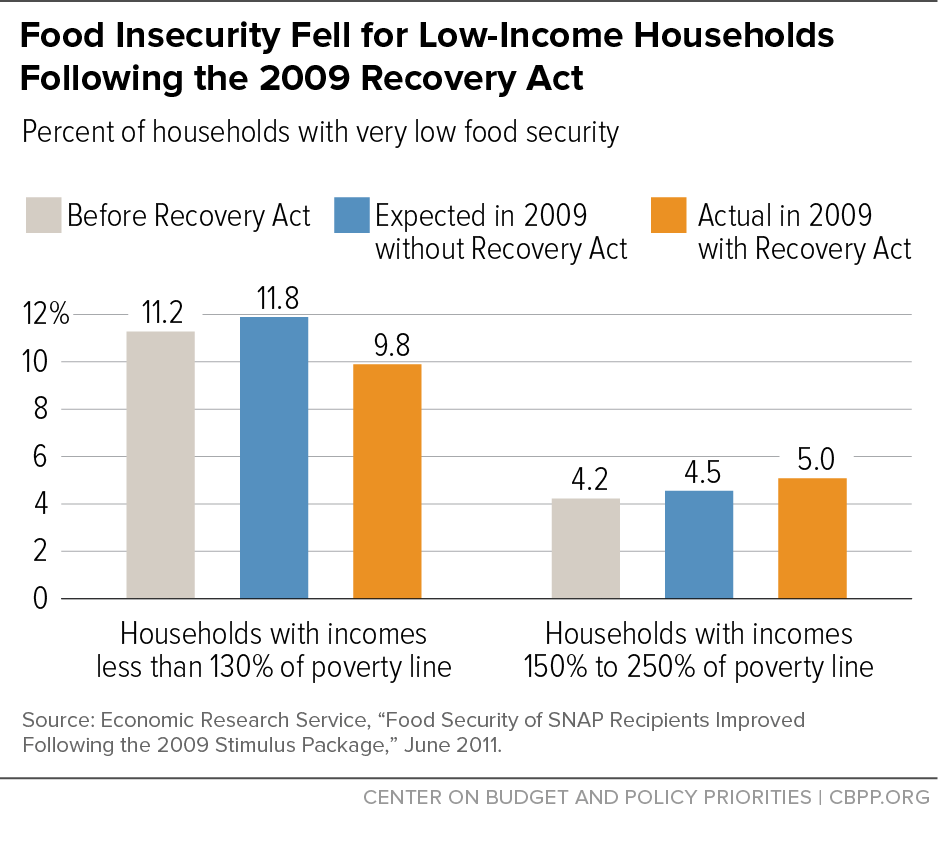

The 2009 Recovery Act boosted SNAP benefits temporarily to stimulate the economy and help needy families during the Great Recession. And, in fact, the CEA report cites a study showing that the share of households with very low food security, meaning they took steps like skipping meals because they couldn’t afford sufficient food, fell in 2009 — despite the recession — among households with incomes low enough to qualify for SNAP. By contrast, among households with somewhat higher incomes, very low food security rose in 2009 as expected (see graph). That suggests the Recovery Act’s benefit increase helped cushion the blow of the recession by providing more income for families to buy food.

Strengthening SNAP benefits like the 2009 Recovery Act did — but on a permanent basis — could ensure that families can put food on the table all month long.