House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan's budget plan specifies a long-term spending path that means that, by 2050, most of the federal government aside from Social Security, health care, and defense would literally cease to exist, according to figures in a Congressional Budget Office report[1] that was released on Tuesday.

CBO's report, prepared at Chairman Ryan's request, also reveals that, as explained below, his plan envisions additional Medicare cuts that were not disclosed in the documents that the chairman released on Tuesday; and his Medicare "premium support" and Medicaid block grant proposals differ substantially from — and have much deeper cuts than — the "Ryan-Rivlin" plan of last fall, which itself was rejected as too severe by the Bowles-Simpson fiscal commission.

On the chairman's plan to dramatically shrink the size and scope of government, the documents that he released show that his plan would shrink federal spending to about 20 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2015 and to 14.75 percent of GDP by 2050 — the lowest level since 1951, a time when Medicare and Medicaid did not exist.

Yet, Medicare and Medicaid would actually fare better than most of the rest of the budget. Perhaps the single most stunning piece of information that the CBO report reveals is that Ryan's plan "specifies a path for all other spending" (other than spending on Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and interest payments) to drop "from 12 percent [of GDP] in 2010 to 6 percent in 2022 and 3½ percent by 2050." [2] These figures are extraordinary. As CBO notes, "spending in this category has exceeded 8 percent of GDP in every year since World War II."[3]

Defense spending has equaled or exceeded 3 percent of GDP every year since 1940, and the Ryan budget does not envision defense cuts in real terms (although defense could decline a bit as a share of GDP). Assuming defense spending remained level in real terms, most of the rest of the federal government outside of health care, Social Security, and defense would cease to exist.

Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform and one of Washington's most influential anti-tax conservatives, told National Public Radio in 2001, "I don't want to abolish government. I simply want to reduce it to the size where I can drag it into the bathroom and drown it in the bathtub." The CBO report suggests that, other than for Social Security, health, and defense, Chairman Ryan has much the same vision.

For Medicare, the CBO report reveals that the Ryan plan would raise the age at which people become eligible from 65 to 67, even as it repeals the health reform law's coverage provisions. This means 65- and 66-year-olds would have neither Medicare nor access to health insurance exchanges in which they could buy coverage at an affordable price and receive subsidies to help them purchase coverage if their incomes are low. This change, which is not mentioned in the 73-page booklet on his plan that Chairman Ryan released,[4] would put many more 65- and 66-year-olds who don't have employer coverage and can't afford insurance into the individual insurance market — where the premiums charged to people in this age group tend to be very high — leaving them uninsured. People of limited means, such as those who are trying to get by on incomes as low as $12,000 a year in today's dollars, would be affected most harshly because they wouldn't be able to afford private coverage.

The CBO report also reveals that the vouchers, or "defined contribution amounts," that Ryan would provide to seniors to buy coverage from private insurance companies in lieu of current Medicare coverage would be adjusted each year only by the general inflation rate. For more than 30 years, health care costs per beneficiary in the United States have been rising about two percentage points per year faster than GDP growth per capita. The Rivlin-Ryan plan of last fall would have provided vouchers that rise with GDP per capita plus one percentage point. But because they would be adjusted only for overall inflation, the vouchers under Ryan's new plan would rise about two percentage points per year less than the Rivlin-Ryan vouchers and about three percentage points per year less than the rate at which health care costs have been growing. Over time, the impact on beneficiaries would be huge, as CBO documents.

Moreover, CBO estimates that the total health care costs attributable to Medicare beneficiaries would be considerably

higher under the private insurance plans they would purchase under the Ryan plan than under a continuation of traditional Medicare, because private plans have higher administrative expenses and higher payment rates for providers. Since the Ryan proposal would

reduce the federal government's contribution for beneficiaries' health care costs even as it caused total costs to

increase, beneficiaries' out-of-pocket spending would rise dramatically.

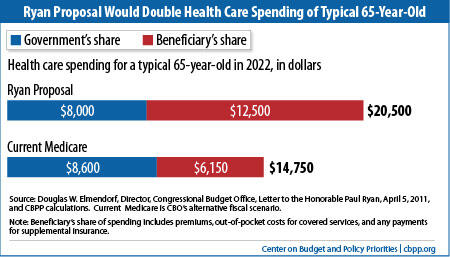

In 2022, the first year the voucher would apply, CBO estimates that total health care expenditures for a typical 65-year-old would be almost 40 percent higher with private coverage under the Ryan plan than they would be with a continuation of traditional Medicare. (See graph.) CBO also finds that this beneficiary's annual out-of-pocket costs would more than double — from $6,150 to $12,500. In later years, as the value of the voucher eroded, the increase in out-of-pocket costs would be even greater.

CBO wrote that "Paying more for health care would be particularly challenging for elderly people with less savings and lower income." [5] And Alice Rivlin said that she does not support Ryan's new proposal. Rivlin observed that it would result in a massive cost-shift over time to beneficiaries and that the growth rate Ryan set for his vouchers is "much, much too low" and "I don't think that's defensible."[6]

For Medicaid, the CBO report similarly reveals that the Medicaid block grant amounts would grow each year only with inflation and U.S. population growth, which is roughly four percentage points less than current projected annual growth in Medicaid (and also well below the annual adjustment level in the Ryan-Rivlin plan).[7] CBO finds that federal funding for Medicaid would fall 35 percent by 2022 — and 49 percent by 2030 — below the levels the federal government now is projected to provide for the program. (This does not count the loss under the Ryan plan of the additional resources that the federal government would spend for Medicaid to cover more of the uninsured under the health reform law.)

The CBO report makes clear that unless states made up the difference, the measures they would have to take as a result of this large loss of funding would include cuts in eligibility (leading to more uninsured low-income people), cuts in covered services (leading to more underinsured low-income people), and/or cuts in already-low payment rates to health care providers (causing doctors, hospitals, and nursing homes to withdraw from Medicaid and thereby reduce beneficiaries' access to care).