- Home

- New CBO Estimates: 23 Million More Unins...

New CBO Estimates: 23 Million More Uninsured Under House-Passed Republican Health Bill

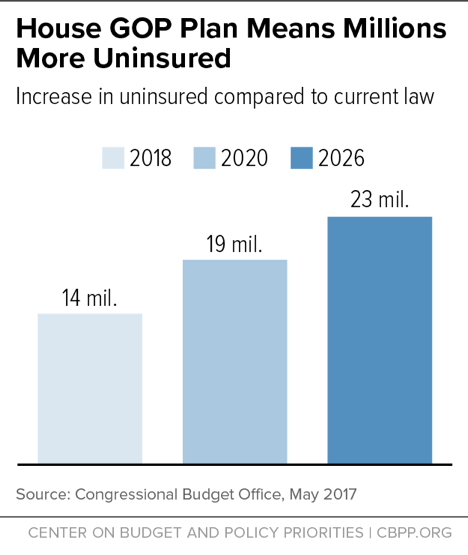

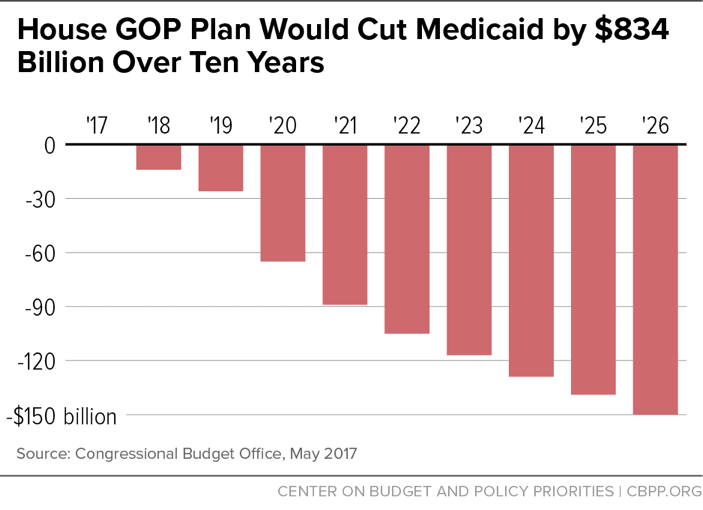

The bill would still reverse all of the historic coverage gains achieved since the ACA was enacted in 2010. Consistent with prior estimates, the House Republican health bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) would cause 23 million people to lose coverage by 2026 and drive $834 billion in federal Medicaid cuts over the next ten years, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) found today.[1] This means the bill would result in nearly the same number of people losing their health insurance coverage as under earlier versions of the bill. It also means that the bill would still reverse all of the historic coverage gains achieved since the ACA was enacted in 2010.

The bill — known as the American Health Care Act (AHCA) and which the House passed on May 4 — would effectively end the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and radically restructure Medicaid by converting virtually the entire program to a per capita cap or block grant starting in 2020. It would also repeal the ACA’s marketplace tax credits and subsidies in 2020, substituting a highly inadequate tax credit, and immediately end the ACA’s individual and employer mandates to buy and provide health coverage, respectively. The House bill would permit states to eliminate critical ACA market reforms and consumer protections including the prohibition against insurers charging higher premiums to people based on their health status or pre-existing conditions, and the requirement that insurers cover essential health benefits like prescription drugs and mental health treatment. The bill would also allow states to drop the bar against insurers charging older people more than three times what they charge younger people.[2]

Among CBO’s key findings:

- In 2018, the number of uninsured would rise by 14 million, relative to current law. That number would further rise to 19 million by 2020. By 2026, the number of uninsured would increase by 23 million — or 82 percent higher than under current law. (See Figure 1.) This means that, by 2026, the historic coverage gains expected under the ACA would be eliminated and the resulting uninsured rate among the non-elderly would be the same as the 2010 level. According to CBO, the increase in the number of uninsured would be disproportionately larger among people aged 55-64 with income less than 200 percent of the federal poverty line.

-

Federal Medicaid spending would be cut by $834 billion or 16.7 percent over the next ten years, relative to current law, due to the effective elimination of the Medicaid expansion and conversion of Medicaid to a per capita cap or block grant. By 2026, the annual cut in federal spending would rise to $150 billion, a reduction of 24 percent, relative to current law. (See Figure 2.) As a result, the number of Medicaid beneficiaries would fall by 14 million in 2026. Most of those losing Medicaid would likely end up uninsured.

-

Altogether, states with about half of the nation’s population will take up waivers allowed under the House bill to eliminate or weaken ACA protections for people with pre-existing conditions in the individual market by dropping the ban on higher premiums based on health status and/or no longer requiring insurers to cover essential health benefits.

States encompassing about one-sixth of the population would allow insurers to widely charge higher premiums based on health status. As a result, people with pre-existing conditions or health status would face “extremely high premiums” according to CBO, and would find it increasingly difficult to purchase health insurance. CBO concludes that the “nongroup markets in those states would become unstable for people with higher-than-average expected health care costs. That instability would cause some people who would have been insured in the nongroup market under current law to be uninsured.”

These states are also projected to eliminate or substantially roll back the essential health benefit requirements through waivers. People living in such states would experience “substantial increases in out-of-pocket spending on health care or would choose to forgo the services” entirely. Such excluded services would include: maternity care, mental health and substance use disorder treatment, rehabilitative and habilitative services, and pediatric dental care. CBO notes that out-of-pocket costs associated with maternity care and mental health and substance abuse services could increase “by thousands of dollars” and that annual and lifetime limits on benefits would also no longer apply.

Other states encompassing another one-third of the population are expected to more moderately weaken either the ban on higher premiums based on health status or on essential benefits.

Those with the greatest health care needs would see their out-of-pocket payments rise the most in states that eliminated or substantially altered both the essential health benefits requirement and the prohibition against charging premiums based on health status.

- Takeup of waivers is the key reason why CBO finds a very modest reduction in the increase in the number of uninsured than under prior versions of the House bill. More healthy people would enroll in individual market coverage as they would be charged lower premiums based on their health status and because they could enroll in skimpier plans with large gaps in benefits as they don’t expect to need much in the way of health care. That would more than offset the losses in coverage among those with pre-existing conditions and greater health needs who face premiums they cannot afford. But that also means that compared to the House bill’s earlier versions, coverage losses would be more concentrated among people with pre-existing conditions and serious health needs — the very people who need health insurance the most.

-

Marketplace enrollees receiving subsidies would face significantly higher premiums and other out-of-pocket costs. CBO has previously noted that the value of the tax credit the House bill provides to purchase health coverage in the individual market would equal only 60 percent of the value of the ACA’s tax credit, falling to 50 percent by 2026. Today’s estimate confirms that older low-income individuals would be particularly hard hit. CBO finds that a typical 64-year-old with income at 175 percent of the federal poverty line would pay, on average, as much as $16,100 more in premiums in 2026 than under current law in a state that doesn’t take up the market reform waivers (and $13,600 more in states that do take up the waivers to make more moderate changes to the market reforms).

In addition, the House bill would eliminate the ACA’s cost-sharing subsidies, which help lower deductibles and copayments for low-income marketplace enrollees, and would not replace them. At the same time, under the House bill, insurers would be permitted to lower the “actuarial value” or the relative generosity of health plans in the individual market, further driving up deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs. And as noted above, states could allow insurers to entirely drop coverage of various benefits or sharply limit their scope. Finally, CBO’s estimates focus on the average impact nationwide and do not take into account how residents of high-cost states[3] or rural areas[4] would experience even larger unaffordable increases in their premiums and other out-of-pocket costs.

- Premiums in the individual market would rise by 20 percent in 2018 and 5 percent in 2019, relative to current law, due to the immediate repeal of the individual mandate as fewer healthy, lower-cost people enroll. In addition, total individual market enrollment would shrink by 8 million in these years. Because of the change in age rating, premiums for older people would sharply increase starting in 2020 and would be more than 20 percent higher by 2026. In combination with the large reduction in subsidies, as noted above, CBO finds that older people with low-incomes would constitute a disproportionately large increase in the uninsured.

End Notes

[1] Congressional Budget Office, “H.R. 1628: American Health Care Act,” May 24, 2017, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/hr1628aspassed.pdf

[2] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “House Health Bill Can’t Be Fixed,” revised May 10, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/the-house-passed-health-bill-cant-be-fixed and Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “House Health Bill Ends Medicaid as We Know It,” May 9, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/house-health-care-bill-ends-medicaid-as-we-know-it.

[3] Aviva Aron-Dine and Tara Straw, “House GOP Health Bill Still Cuts Tax Credits, Raises Costs by Thousands of Dollars for Millions of People,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 22, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/house-gop-health-bill-still-cuts-tax-credits-raises-costs-by-thousands-of-dollars.

[4] Jesse Cross-Call et al., “House-Passed Bill Would Devastate Care in Rural America,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 16, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/house-passed-bill-would-devastate-health-care-in-rural-america.