- Home

- SNAP: Combating Fraud And Improving Prog...

SNAP: Combating Fraud and Improving Program Integrity Without Weakening Success

Testimony of Stacy Dean, Vice President for Food Assistance Policy,

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities,

Before the Subcommittees on Government Operations and the Interior of the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

U.S. House of Representatives

Thank you for the opportunity to testify today. I am Stacy Dean, Vice President for Food Assistance Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, an independent, non-profit, nonpartisan policy institute located here in Washington. The Center conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting low- and moderate-income families. The Center’s food assistance work focuses on improving the effectiveness of the major federal nutrition programs, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). I have worked on SNAP policy and operations for more than 20 years. Much of my work is providing technical assistance to state officials who wish to explore options and policy to improve their program operations in order to more efficiently serve eligible households. My team and I also conduct research and analysis on SNAP at the national and state levels. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities receives no government funding.

My testimony today is divided into two sections: 1) SNAP’s role in our country as a federal nutrition program; and 2) an overview of how SNAP addresses and maintains program integrity.

I. SNAP Plays a Critical Role in Our Country

Before turning to today’s hearing topic of SNAP’s program integrity, I think it is important to review some of SNAP’s most critical features. The program is a highly effective anti-hunger program. Much of the program’s success is due to its entitlement structure, its consistent national benefit structure, and its food-based benefits. The program also imposes rigorous requirements on states and clients to ensure a high degree of program integrity.

As of February this year, SNAP was helping more than 44 million low-income Americans to afford a nutritionally adequate diet by providing them with benefits via a debit card that can be used only to purchase food. On average, SNAP recipients receive about $1.39 per person per meal in food benefits. One in seven Americans is participating in SNAP — a figure that speaks both to the extensive need across our country and to SNAP’s important role in addressing it.

Policymakers created SNAP to help low-income families and individuals purchase an adequate diet. It does an admirable job of providing poor households with basic nutritional support and has largely eliminated severe hunger and malnutrition in the United States. As I will discuss later, it accomplishes these critical goals while maintaining sound program integrity.

When the program was first established, hunger and malnutrition were much more serious problems in this country than they are today. A team of Field Foundation-sponsored doctors who examined hunger and malnutrition among poor children in the South, Appalachia, and other very poor areas in 1967 (before the Food Stamp Program, as SNAP was then named, was widespread in these areas) and again in the late 1970s (after the program had been instituted nationwide) found marked reductions over this ten-year period in serious nutrition-related problems among children. The doctors gave primary credit for this reduction to the Food Stamp Program. Findings such as this led then-Senator Robert Dole to describe the Food Stamp Program as the most important advance in the nation’s social programs since the creation of Social Security.

Consistent with its original purpose, SNAP continues to provide a basic nutrition benefit to low-income families, the elderly, and people with disabilities who cannot afford an adequate diet. In some ways, particularly in its administration, today’s program is stronger than at any previous point. By taking advantage of modern technology and business practices, SNAP has become substantially more efficient, accurate, and effective. While many low-income Americans continue to struggle, this would be a very different country without SNAP.

SNAP Protects Families From Hardship and Hunger

SNAP benefits are an entitlement, which means that anyone who qualifies under the program’s rules can receive benefits. This is the program’s most powerful feature: it enables SNAP to respond quickly and effectively to support low-income families and communities during times of economic downturn and increased need. Aided by a temporary benefit increase from the 2009 Recovery Act, SNAP kept poverty and food insecurity (lack of consistent access to sufficient food) from rising during the Great Recession as much as they would have without the program.[1]

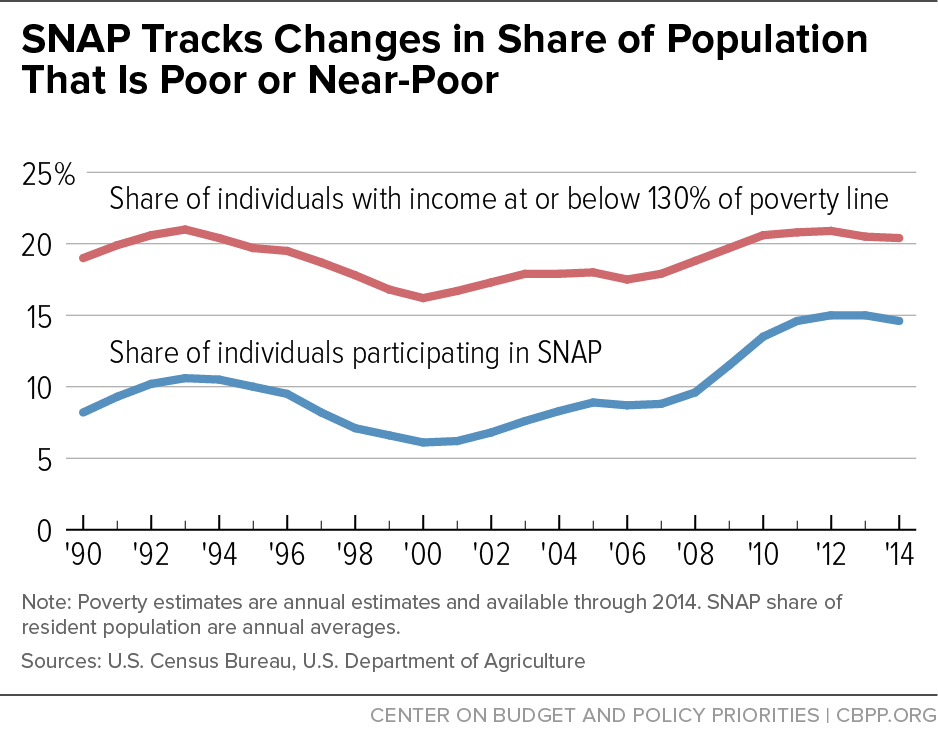

Enrollment expands when the economy weakens and contracts when the economy recovers. (See Figure 1.) As a result, SNAP responds immediately to help families and to bridge temporary periods of unemployment. It also can help individual families weather a short-term crisis, such as separation or divorce. . A U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) study of SNAP participation over the late 2000s found that slightly more than half of all new entrants to SNAP participated for less than one year and then left the program when their immediate need passed.

SNAP’s powerful response during the recession is in sharp contrast to that of the cash assistance program Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), whose block grant structure sharply limits its ability to expand during economic downturns. TANF enrollment did not rise significantly as the number of people in poverty rose during the recession. While the number of unemployed doubled in the Great Recession, TANF caseloads rose only modestly, by 13 percent from December 2007 to December 2009.

SNAP’s ability to serve as an automatic responder is also important when natural disasters strike. States can provide emergency SNAP within a matter of days to help disaster victims purchase food. In 2014 and 2015, for example, SNAP helped households in the Southeast affected by severe storms and flooding and households on the west coast affected by wildfires.

SNAP’s caseloads grew in recent years primarily because of its role as an automatic stabilizer: more households qualified for SNAP because of the recession, and the number of eligible households stayed high in the years following the recession because of the slow recovery. During the recession, as the official poverty rate rose from 12.5 percent to 15.1 percent, SNAP enrollment rose to respond to this increase. Poverty stayed high through 2014 (the most recent year for which data are available), at 14.8 percent, and as a result, though SNAP participation has begun to fall, it remains high compared to pre-recession levels.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has confirmed that “the primary reason for the increase in the number of participants was the deep recession . . . and subsequent slow recovery; there were no significant legislative expansions of eligibility.”[2] Emerging research on the Great Recession finds that indeed, economic factors were the main drivers of SNAP caseload increases during this period, explaining between about half and 90 percent of the increase in SNAP caseloads between 2007 and 2011. One study, which tested different measurements of the economy and SNAP caseloads at the state and local levels, found that the economy explained 70 to 90 percent of the increase in caseloads; it also found substantial lags — of up to two years — between changes in the economy and changes in SNAP participation.[3]

Another important factor in rising caseloads during and after the recession is that a larger share of eligible households applied for help. Participation rates among eligible people grew from 69 percent in 2007 to 83 percent in 2014 (the most recent year available). Several factors likely contributed to these rising rates. The widespread and prolonged effects of the recession, particularly the record long-term unemployment, may have made it more difficult for family members and communities to help people struggling to make ends meet. Households that already were poor became poorer during the recession and may have been in greater need of help. In addition, states continued efforts begun before the recession to reach more eligible households — particularly working families and senior citizens — by simplifying SNAP policies and procedures.

While SNAP’s growth was substantial, SNAP participation and spending have begun to decline as the economic recovery has begun to reach low-income SNAP participants. In 2014 and 2015 SNAP caseloads declined in most states; as a result, the national SNAP caseload fell by 2 percent both years. Nationally, for the last two and a half years, fewer people have participated in SNAP each month than in the same month of the prior year. SNAP caseloads have fallen by more than 3 million people over the last three years: about 3.2 million fewer people participated in SNAP in February 2016 than in February 2013, and about 3.4 million fewer people than in December 2012, when participation peaked. The declines have been widespread: 43 states had fewer SNAP participants in February 2016 than in February 2013.

As a result of this caseload decline, spending on SNAP as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell by 4 percent in 2015. In 2014 it fell by 11 percent, largely due to the expiration of the Recovery Act’s SNAP benefit increase. CBO predicts that this trend will continue, and that SNAP spending as a share of GDP will fall to its 1995 levels by 2020.

SNAP Lessens the Extent and Severity of Poverty and Unemployment

SNAP targets benefits on those most in need and least able to afford an adequate diet. Its benefit formula considers a household’s income level as well as its essential expenses, such as rent, medicine, and child care. Although a family’s total income is the most important factor affecting its ability to purchase food, it is not the only factor. For example, a family spending two-thirds of its income on rent and utilities will have less money to buy food than a family that has the same income but lives in public or subsidized housing.

While the targeting of benefits adds some complexity to the program and is an area where states sometimes seek to simplify, it helps ensure that SNAP provides the most assistance to the poorest families with the greatest needs.

This makes SNAP a powerful tool in fighting poverty. A CBPP analysis using the government’s Supplemental Poverty Measure, which counts SNAP as income, and that corrects for underreporting of public benefits in survey data, found that SNAP kept 10.3 million people out of poverty in 2012, including 4.9 million children. SNAP lifted 2.1 million children above 50 percent of the poverty line in 2012, more than any other benefit program.

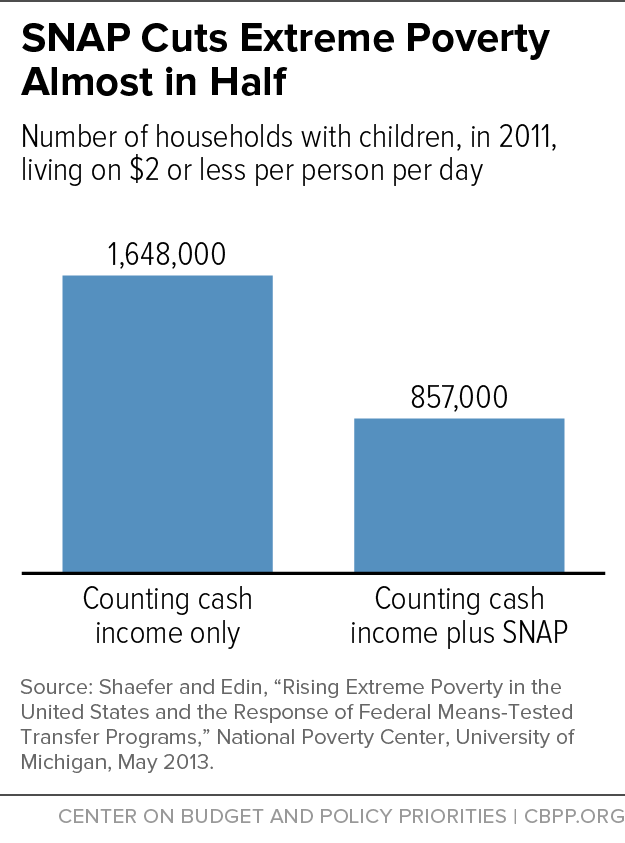

SNAP is also effective in reducing extreme poverty. A recent study by the National Poverty Center estimated the number of U.S. households living on less than $2 per person per day, a classification of poverty that the World Bank uses for developing nations. The study found that counting SNAP benefits as income cut the number of extremely poor households in 2011 by nearly half (from 1.6 million to 857,000 - see Figure 2).

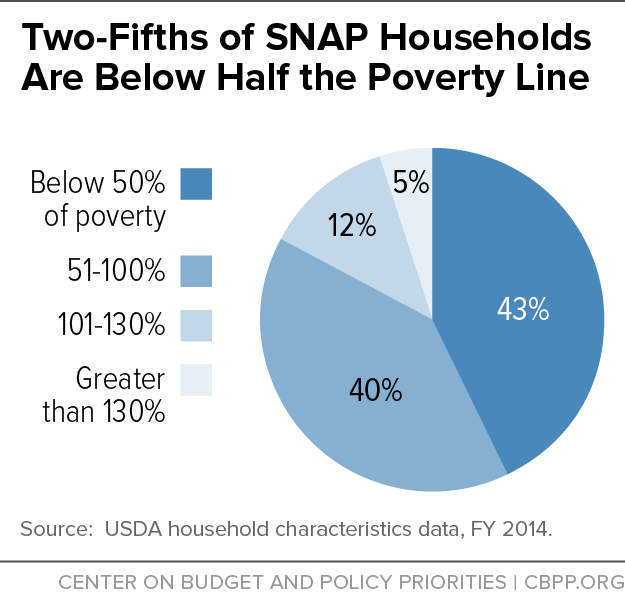

SNAP is able to achieve these results because it is so targeted at very low-income households. Roughly 93 percent of SNAP benefits goes to households with incomes below the poverty line, and 58 percent goes to households with incomes below half of the poverty line (about $10,045 for a family of three in 2016). (See Figure 3.)

By providing low-income families with more income to purchase food than their limited budgets otherwise would allow, SNAP also reduces the burden of food insecurity for families. A study that compared SNAP participant households before and after six months of participating in SNAP found that SNAP reduced food insecurity by up to ten percentage points, or 17 percent, and also reduced “very low food security,” which occurs when one or more household members have to skip meals or otherwise eat less because they lack money, by about six percentage points.

During the deep recession and still-incomplete recovery, SNAP has become increasingly valuable for the long-term unemployed as it is one of the few resources available for jobless workers who have exhausted their unemployment benefits. Long-term unemployment hit record highs in the recession and remains unusually high; in May 2016, about a quarter (25.1 percent) of the nation’s 7.4 million unemployed workers had been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. That’s much higher than it’s ever been (in data back to 1948) when overall unemployment has been so low.

SNAP also protects the economy as a whole by helping to maintain overall demand for food during slow economic periods. In fact, SNAP benefits are one of the fastest, most effective forms of economic stimulus because they get money into the economy quickly. Moody’s Analytics estimates that in a weak economy, every $1 increase in SNAP benefits generates about $1.70 in economic activity (i.e., increase in economic activity and employment per budgetary dollar spent), and is one of the most effective forms of stimulus among a broad range of policies for stimulating economic growth and creating jobs in a weak economy.

SNAP Improves Long-term Health and Self-sufficiency

While reducing hunger and food insecurity and lifting millions out of poverty in the short run, SNAP also brings important long-run benefits.

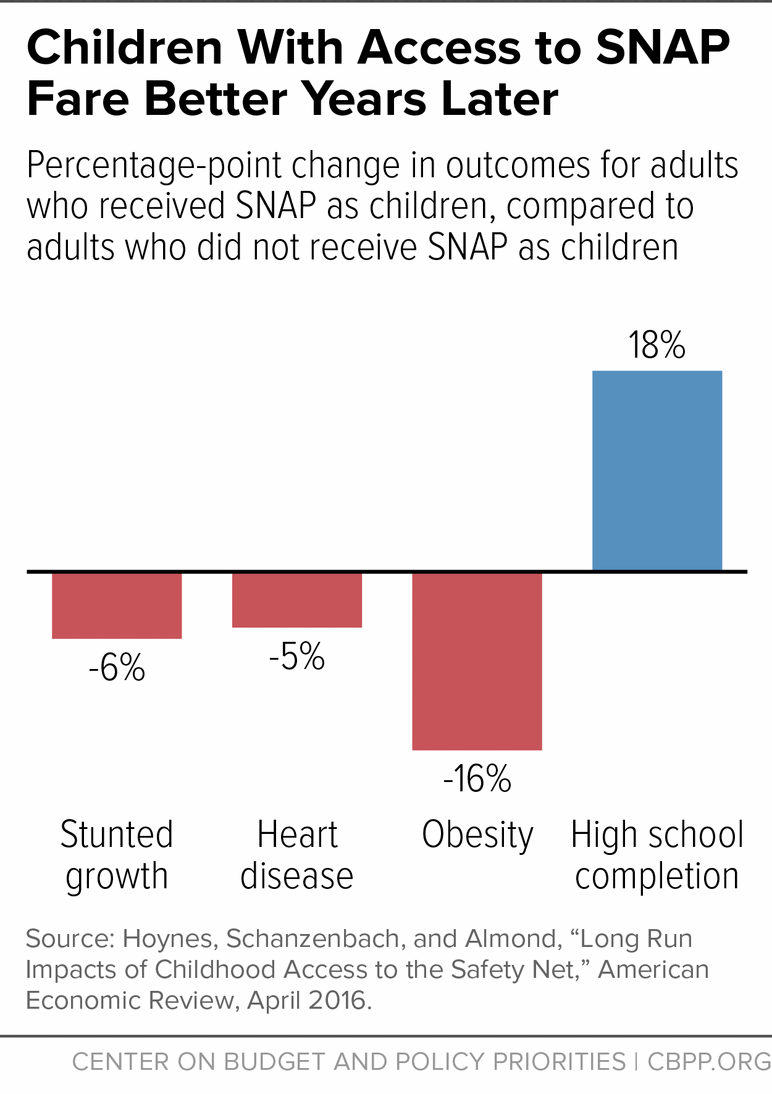

A recent study published in the American Economic Review examined what happened when the government introduced food stamps in the 1960s and early 1970s and concluded that children who had access to food stamps in early childhood and whose mothers had access during their pregnancy had better health outcomes as adults years later, compared with children born at the same time in counties that had not yet implemented the program. Along with lower rates of “metabolic syndrome” (obesity, high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes), adults who had access to food stamps as young children reported better health, and women who had access to food stamps as young children reported improved economic self-sufficiency (as measured by employment, income, poverty status, high school graduation, and program participation).[4] (See Figure 4.)

Supporting and Encouraging Work

In addition to acting as a safety net for people who are elderly, disabled, or temporarily unemployed, SNAP is designed to supplement the wages of low-income workers.

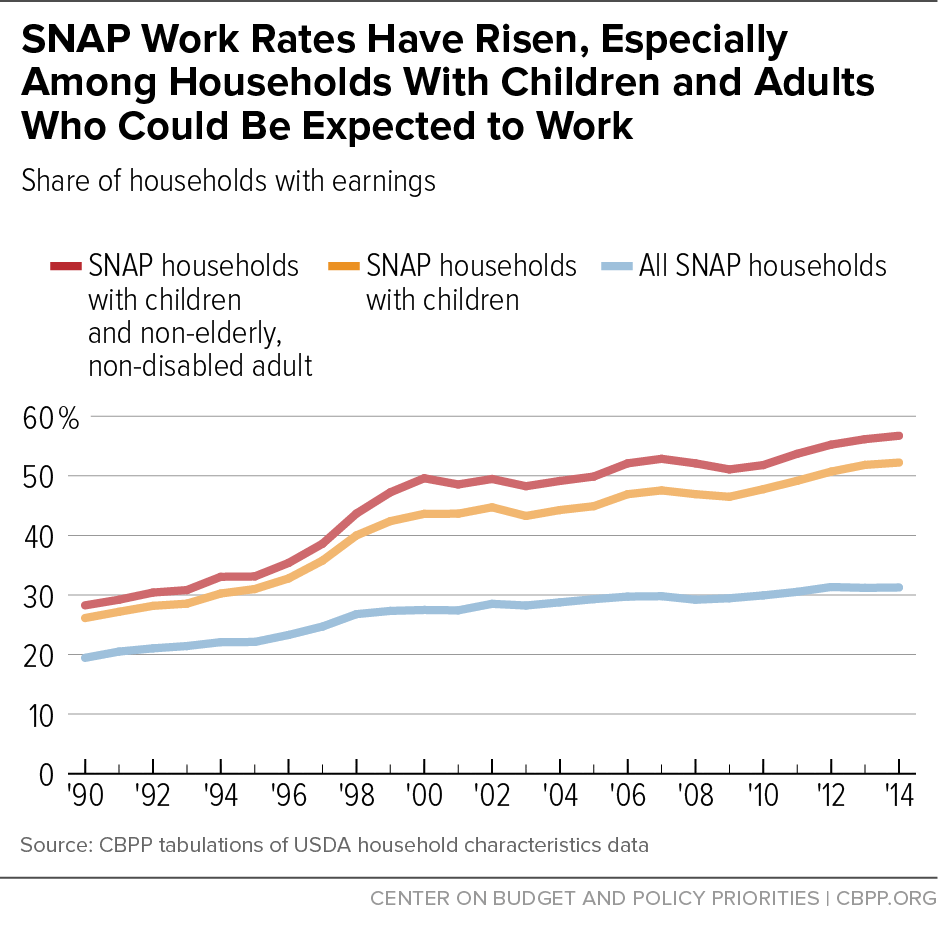

The number of SNAP households that have earnings while participating in SNAP has more than tripled — from about 2 million in 2000 to about 7 million in 2014. The share of SNAP families that are working while receiving SNAP assistance has also been rising — while only about 28 percent of SNAP families with an able-bodied adult had earnings in 1990, 57 percent of those families were working in 2014. (See Figure 5.)

The SNAP benefit formula contains an important work incentive. For every additional dollar a SNAP recipient earns, her benefits decline by only 24 to 36 cents — much less than in most other programs. Families that receive SNAP thus have a strong incentive to work longer hours or to search for better-paying employment. States further support work through the SNAP Employment and Training program, which funds training and work activities for unemployed adults who receive SNAP.

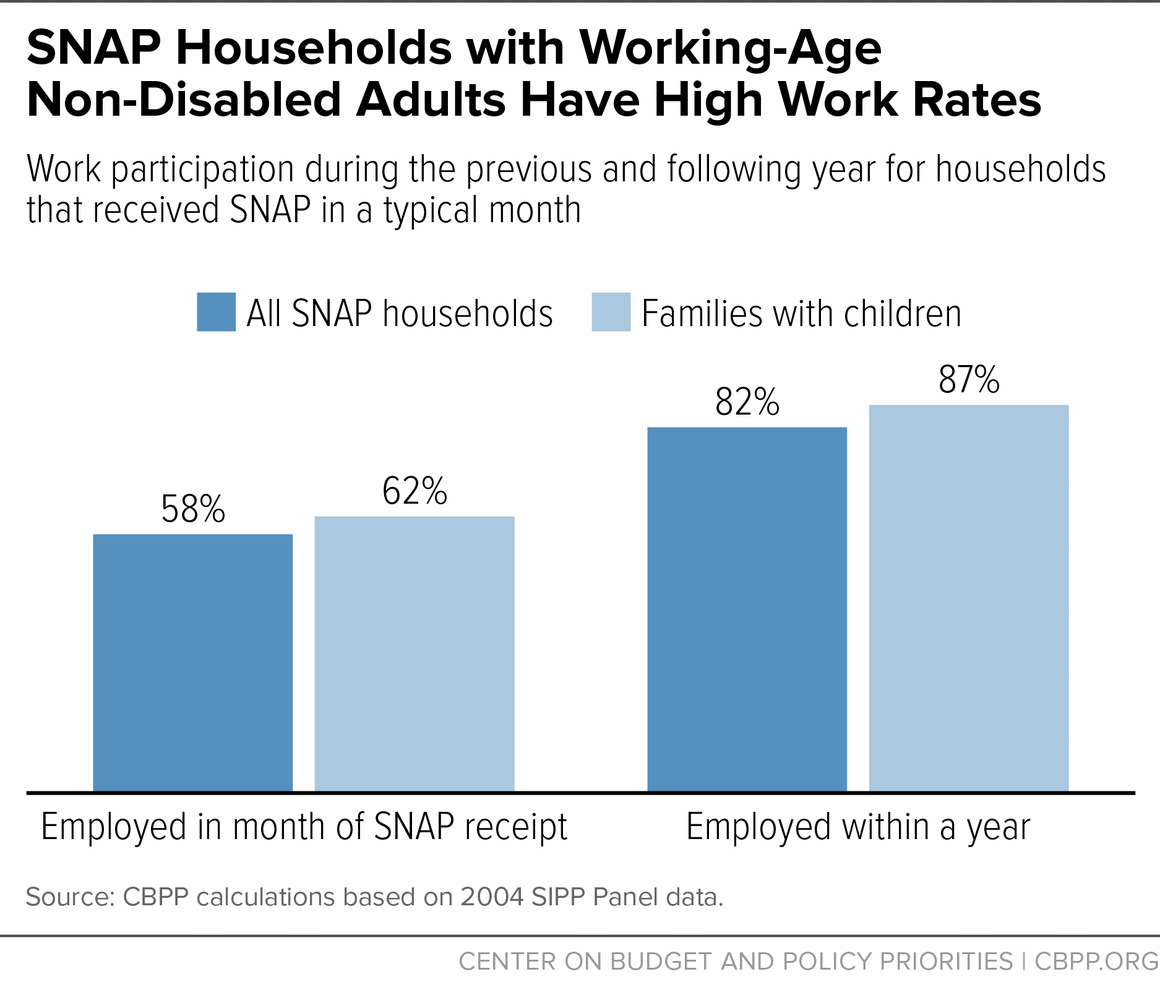

Most SNAP recipients who can work do so. Among SNAP households with at least one working-age, non-disabled adult, more than half work while receiving SNAP — and more than 80 percent work in the year prior to or the year after receiving SNAP. The rates are even higher for families with children. (See Figure 6.) (About two-thirds of SNAP recipients are not expected to work, primarily because they are children, elderly, or disabled.)

II. SNAP Prioritizes Program Integrity

While SNAP’s primary purpose is to help struggling households afford a basic diet, the program cannot achieve its goal without maintaining strong program integrity. USDA and states take their roles as stewards of public funds seriously and emphasize program integrity throughout program operations. Moreover, the authorizing committees have mandated in SNAP some of the most rigorous program integrity standards and systems of any federal program. They provide oversight of the program’s accuracy and fraud detection and prevention systems. These strong systems ensure a high degree of integrity and accuracy in the program.

SNAP’s eligibility assessment and standards for review are robust. States determine SNAP eligibility and benefits based on an assessment of a household’s current income, certain deductible expenses, and household characteristics. When a household applies for SNAP it must report its income and other relevant information; a state eligibility worker interviews a household member and verifies the accuracy of the information using third-party data matches, paper documentation from the household, and/or by contacting a knowledgeable party, such as an employer or landlord. Households must reapply for benefits periodically, usually every six or 12 months, and between reapplications must report income changes that would affect their eligibility. This is generally a more robust assessment of financial need that other programs employ.

SNAP has numerous measures to ensure the accurate assessment of household eligibility during the eligibility process, through ongoing checks and reassessment of eligibility. The same is true with respect to the proper use of benefits, an area of fraud prevention and detection where USDA also plays a significant role. These measures are designed to detect and prevent the occurrence of honest mistakes, careless errors, systemic mistakes, and the less frequent problem of intentional fraud.

They include extensive requirements that households applying for or seeking to continue receiving SNAP prove their eligibility, sophisticated computer matches to detect unreported earnings, a Quality Control (QC) system that is the most rigorous of any public benefit program, and administrative and criminal enforcement mechanisms. My experience with SNAP program integrity issues is primarily in the area of program policy and state operations: the eligibility process, ongoing eligibility checks via third-party data matching, coordinating SNAP with other programs, and quality control. I will review several of the key program integrity measures in the program.

Strong Eligibility and Payment Accuracy Backed Up by Quality Control System

SNAP has long had one of the most rigorous payment error measurement systems of any public benefit program. When, under the leadership of this Committee, Congress enacted the Improper Payments Act in the early 2000s to establish a framework for federal agencies to reduce improper payments, SNAP was among the few programs to already meet the Act’s high standards. Each year states take a representative sample of SNAP cases (totaling about 50,000 cases nationally) and thoroughly review the accuracy of their eligibility and benefit decisions. Federal officials re-review a subsample of the cases to ensure accuracy in the error rates. States are subject to fiscal penalties if their error rates are persistently higher than the national average.

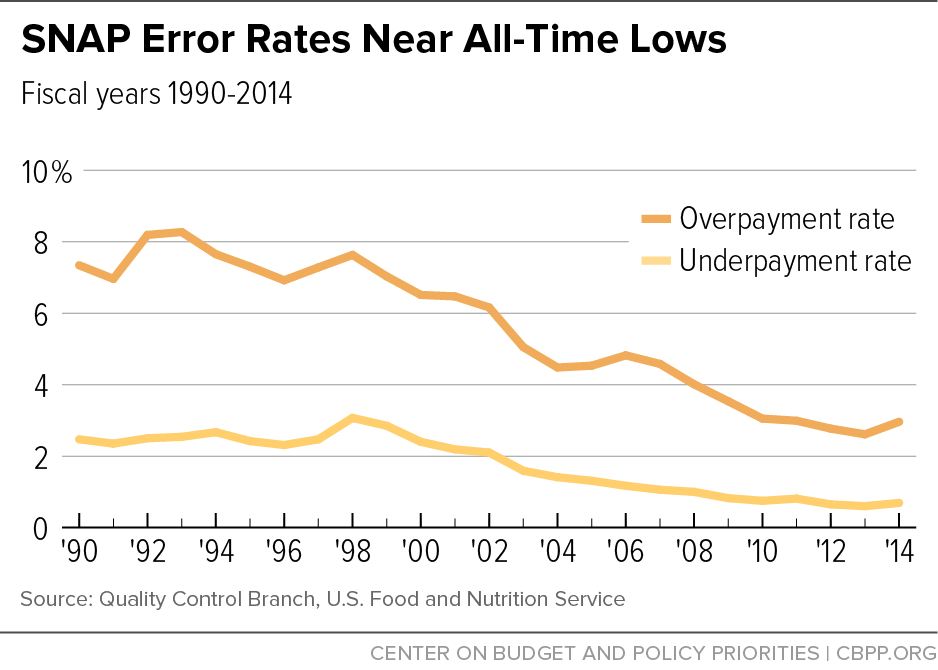

The percentage of SNAP benefit dollars issued to ineligible households or to eligible households in excessive amounts fell for seven consecutive years and stayed low in 2014 at 2.96 percent, USDA data show. The underpayment error rate also stayed low at 0.69 percent. The combined payment error rate — that is, the sum of the overpayment and underpayment error rates — was 3.66 percent, low by historical standards.[5] Less than 1 percent of SNAP benefits go to households that are ineligible. (See Figure 7.)

If one subtracts underpayments (which reduce federal costs) from overpayments, the net loss to the government in FY2014 from errors was 2.27 percent of benefits.

In comparison, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) estimates an average tax noncompliance rate of 18.3 percent for tax years 2008 through 2010 (the most recently studied years). This represents a $458 billion loss to the federal government in one year. Underreporting of business income alone cost the federal government an average of $125 billion per year between 2008 and 2010, and nonfarm sole proprietors underreport their income by 63 percent.[6]

The overwhelming majority of SNAP errors that do occur result from mistakes by recipients, eligibility workers, data entry clerks, or computer programmers, not dishonesty or fraud by recipients. In addition, states have reported that almost 60 percent of the dollar value of overpayments and almost 90 percent of the dollar value of underpayments were their fault, rather than recipients.’ Much of the rest of overpayments resulted from innocent errors by households facing a program with complex rules.

It should be noted that an overpayment is counted in a state’s error rate whether or not the overpaid benefits are collected back from households. In fiscal year 2014, states collected about $340 million in overissued benefits.[7]

Finally, it cannot be overstated how much emphasis on achieving and maintaining low payment error rates pervades SNAP’s operational culture. USDA and the states, which administer SNAP under federal guidelines, monitor SNAP error rates throughout the year and share best practices. A significant number of federal and state personnel are assigned to program integrity.[8] The error rate is the major performance measure for accountability at state and local SNAP offices and even for individual SNAP state eligibility workers and policy officials.

The impact of operational or policy decisions on state error rates is almost always a consideration as to whether a state adopts a change. In the past, fear of high error rates has sometimes driven states to adopt policies that deterred access. This was most pronounced in the late 1990s when the share of households with earnings on SNAP began to rise (as a result of the strong economy and policies enacted in welfare reform). Low-income earners often experience sharp fluctuations in their monthly income, making household income difficult to predict accurately for SNAP benefit calculations. Some states instituted administrative practices designed to reduce errors that had the unintended effect of making it harder for many working-poor parents to participate, largely by requiring them to take too much time off from work for repeated visits to SNAP offices at frequent intervals, such as every 90 days, to reapply for benefits.

This prompted many analysts and state policy officials from across the political spectrum to call for reforms to policy and quality control that would improve access to SNAP for low-income working families, and led both the Clinton and the Bush administrations to act to address this problem. There was bipartisan consensus that having a policy under which a family needed to be on welfare to receive food stamps, and faced significant difficulty receiving food stamp assistance if it left welfare for work at low wages, would reduce incentives to work and was contrary to welfare reform goals. Congress enacted significant, although relatively modest, changes in 2002 and 2008 to modify program rules that would lessen barriers to SNAP participation among the working poor without compromising program integrity.

High Improper Benefit Denials Raise Concerns

Through the SNAP QC system, USDA and states also monitor “case and procedural error rates” (CAPERs), which measure whether the state properly denied, suspended, or terminated SNAP benefits to certain households and properly notified those households of its decision.[9] USDA and states implemented new procedures for these error rates in 2012, which now hold states more accountable for the timeliness, accuracy, and clarity of the notices states send to households regarding their decisions. This improvement is important so that eligible households who are denied have the specific information necessary to clarify their circumstances or provide missing documentation.

For example, prior to these changes, one state’s notice informed denied households that the household was denied eligibility because “You did not do what you needed to do to meet all of the program rules, according to the code of regulations.” [10] Reading such a notice, a household would have no way of knowing why it was determined ineligible for the program. This undermines the purpose of the notice, which is to provide sufficient information regarding the reasons why a household was denied so that an eligible household can appeal an incorrect decision or provide new information to reverse the decision (i.e., due process). Today, such a notice would be an improperly denied case because it does not adequately inform the household of the reason its application was denied (such as that it did not provide a particular pay stub or missed a scheduled interview).

Nationally, in 2014 over one-quarter of states’ actions to deny or terminate SNAP benefits were found to be improper. Eight states’ CAPERs approached or exceeded 50 percent.[11] The CAPER is not directly comparable to the overpayment and underpayment error rates. It is based on a separate state sample of denials, suspensions, and terminations, and the review of the state’s decision is not as rigorous as for the payment errors. USDA does not assess or report whether the household was ineligible for a reason other than the reason given by the state or the amount of benefits that improperly denied households should have received. Also, states are not penalized for persistently high CAPERs (though they can receive a performance bonus for low or improving CAPERs, as discussed below). We anticipate that, as states reconsider and redesign their denial procedures, adjust to the new measurement regime, and improve their notices, the CAPER rate will improve.

SNAP Provides for a Strong Anti-Fraud System

Fraud, while relatively rare, is taken seriously in the program. Within the SNAP context, fraud is defined to mean occurrences where:

- SNAP benefits are exchanged for cash. This is called trafficking and it is against the law. Trafficking involves two parties — typically a household and a SNAP retailer.

- A household intentionally lies to the state to qualify for benefits or to get more benefits than they are supposed to receive.

- A retailer has been disqualified from the program for past abuse and lies on the application to get into the program again.

States and USDA each play a role in pursuing these different kinds of fraud, dedicating significant resources and staff to pursing allegations of fraud and rooting it out when found. My testimony will briefly cover two of these issues: household fraud and trafficking.

Household Fraud

As with payment accuracy, SNAP’s rigorous application process and eligibility review serves as the first line of fraud prevention. The program’s design is based on a robust review of current household income and circumstances, setting a serious tone and make it difficult for an individual to casually lie in order to get benefits. The application process requires an interview with a caseworker and demands that, in addition to mandated verification (and often third-party data checks), any questionable information provided by the applicant be verified. For example, if an individual claims that its rent is $1,000 a month but it has no income, there is a question about how the household is affording its rent. If a caseworker were to accept such a statement without probing, the case could be in error — because the client was either confused about what counts as income (i.e., not counting support from a friend or family member) or did not tell the whole truth about its situation. The caseworker should follow up on this information at the interview and require additional verification from the individual before he or she is approved. States can set their own filters on what provokes further follow-up based on individual circumstances.

Caseworkers feel appropriate pressure to ensure benefits are issued accurately. There is the formal QC review process, and many states do quality and accuracy reviews of staff work at the line manager level. Managers will review a certain number of cases from each worker each month — generally focusing on less experienced workers. This provides another spot check for quality and fraud detection as well as keeping managers informed of which areas of the program rules and processes might need additional training.

In addition to requiring applicants to provide verification, state agencies run database checks to match the information provided by applicants. For example if an application lists Social Security as a source of income, the eligibility worker reviewing the case would check with the Social Security Administration to verify the amount of the monthly payment. In many instances the database checks provide real-time data, meaning that a caseworker can reconcile information discrepancies on the application while talking with the applicant. An area for program improvement would be for Congress to consider providing all states with this capacity.

Once a household is determined eligible for the program, it has to remain eligible to continue to participate. It must report changes that would make it income-ineligible. And many states run third-party matches throughout a household’s eligibility cycle to continue to check that external information confirms the household’s circumstances. For example, Congress has mandated that states check with prison records and state vital statistics to ensure that no member of a SNAP household continues to receive benefits during incarceration or after death.

When a caseworker suspects that a client is not telling the truth and is seeking to deceive the program, the case is referred to the state’s fraud unit. Member of the public and other state agencies may similarly report any suspected fraud. Most states prominently display fraud hotlines on their main webpages or take other steps to make it easy for the public to report fraud. [12]

States must have fraud investigative units or staff so that allegations of fraud by the public or other agencies or referrals from eligibility caseworkers can be assessed. When referrals are made to the fraud unit, fraud investigators review whether the case is worthy of pursuit. If so, they investigate to determine whether the individual committed fraud. Many investigations do not result in a fraud finding. Out of the over 640,000 fraud investigations in fiscal year 2014, 54 percent of the cases were determined to not be fraud.[13] When the fraud investigators gather enough evidence to make a case that fraud has occurred, there is typically a hearing where the facts are reviewed and clients have an opportunity to dispute the allegations. This process is in place so that those who have committed fraud are disqualified from the program, while innocent participants who made unknowing mistakes are not.

If found guilty of fraud, a person loses SNAP eligibility. In addition, states pursue the improperly issued benefits for repayment via SNAP’s claims process. States are eligible to retain a share of mis-issued benefits that they collect as an incentive for them to pursue the claims.

| Fraud Violation | Penalty |

|---|---|

| First fraud/intentional program violation | 12-month disqualification period |

| Second fraud/intentional program violation | 24-month disqualification period |

| Third fraud/intentional program violation | Permanent disqualification from SNAP |

| False statement with respect to identity or place or residence in order to receive multiple SNAP benefit simultaneously | 10-year disqualification period |

In fiscal year 2014, 45,000 individuals were disqualified from SNAP for fraud, up slightly from 43,000 in fiscal year 2013.[14]

Trafficking

- Another area of program integrity in which SNAP has a strong systems and has made considerable improvements is trafficking, or the sale of SNAP benefits for cash, which violates federal law. USDA has cut trafficking by three-quarters over the past 15 years. About 1 percent of SNAP benefits now are trafficked.[15]

- A key tool in reducing trafficking has been the replacement of food stamp coupons with electronic debit cards like the ATM cards that most Americans carry in their wallets, which recipients can use in the supermarket checkout line only to purchase food.

- Sophisticated computer programs monitor SNAP transactions for patterns that may suggest abuse; federal and state law enforcement agencies are then alerted and investigate. Retailers or SNAP recipients who defraud SNAP by trading their benefit cards for money or misrepresenting their circumstances could face criminal penalties.

- Over the years, USDA has sanctioned thousands of retail stores for not following federal requirements. In fiscal year 2015, USDA permanently disqualified over 1,900 SNAP retailers for program violations and imposed sanctions, through fines or temporary disqualifications, on another 800 stores.[16]

USDA also partners with state SNAP agencies to combat trafficking. In 2014, USDA provided over $5 million to states to use technology to identify possible fraudulent activity and to increase the number of trafficking investigations. The 2014 Farm Bill provided $7.5 million for states to create or improve technology systems designed to prevent, detect, and prosecute trafficking. USDA recently awarded such grants to five states.[17]

SNAP Administration Is Efficient

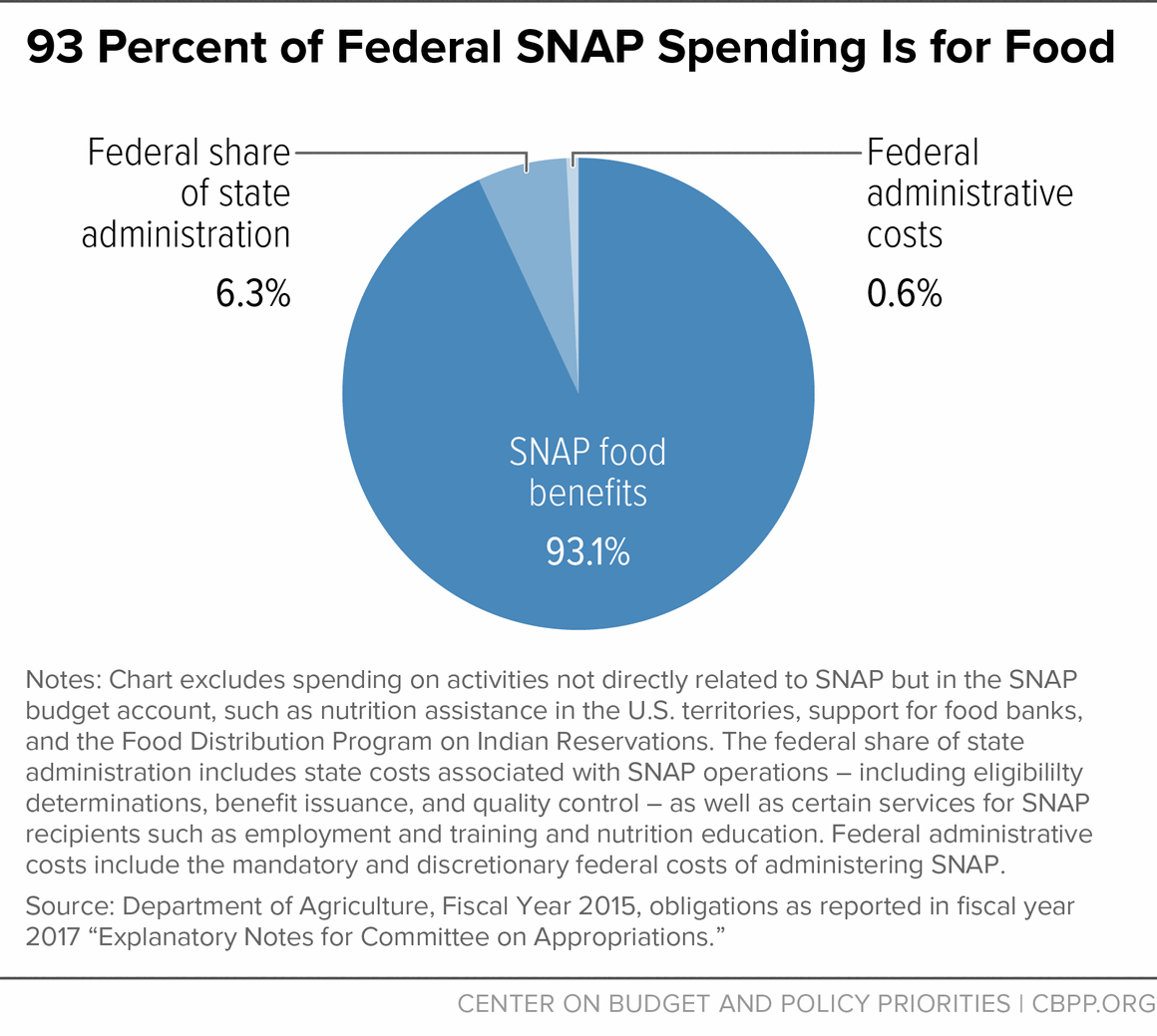

Finally, it is worth noting that SNAP is able to accomplish these results with low administrative overhead. About 93 percent of federal SNAP spending goes to providing benefits to households for purchasing food. (See Figure 8.) Of the remaining 7 percent, about 6 percent was used for state administrative costs, including eligibility determinations, employment and training and nutrition education for SNAP households, and anti-fraud activities. Less than 1 percent went to federal administrative costs. In addition to SNAP, the SNAP budget funds $2.4 billion in other food assistance programs, including a block grant for food assistance in Puerto Rico and American Samoa, commodity purchases for the Emergency Food Assistance Program (which helps food pantries and soup kitchens across the country), and commodities for the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations.

What Else Can Be Done to Enhance Program Integrity?

We support the ongoing effort to work to maintain and improve SNAP’s program integrity. As new technology becomes available and as awareness of how problems arise improves, there will continue to be opportunities to improve SNAP accuracy and prevent fraud. And, with respect to fraud, while a relatively small problem, it’s an ever-changing concern. Criminals are adaptable, and the government’s response to them must also remain nimble and responsive to current patterns of fraud.

Often, our biggest obstacle to helping states implement new measures that would increase the accuracy of benefit issuance is cost. Modernized eligibility systems, access to useful third-party data and the appropriate level of staff to process cases with a high degree of accuracy can be costly for states. While the federal government shares in the costs of administering the program, state budgets are the limiting factor to ensuring the best systems and technology are deployed throughout the program. Many states downsized their program operations during the recent recession and have not yet rebuilt the capacity necessary to take full advantage of new options and technology.

As the Committee considers new ideas to improve program integrity in SNAP or any other major benefits program, we encourage you to assess whether new ideas are worthy of consideration against several criteria.

- What is the scope and scale of the problem under discussion? Some of the most egregious examples of fraud are highly isolated incidences of criminal activity. To be sure, they are completely unacceptable, but they may be so infrequent that they should not drive the program’s fundamental approach to addressing more common, everyday program integrity issues. In the case of error, scope and scale also matter. States may fail to act on data showing that some individuals are no longer eligible for the program. It’s useful to assess the problem and the possible solutions, based on whether the problem involves, for example, 40 or 4,000 individuals. Neither is acceptable, but each situation would likely warrant a different level of response. Often auditors or reviewers give the same headline to each type of problem, which can distort the response.

- What are the projected costs and benefits associated with the proposed solution? It’s always sensible to review project costs and savings related to proposed activities. We find, however, that when a proposal is promoted as an anti-fraud activity, some are reluctant to weigh the pros and cons out of fear of being perceived as soft on fraud. A good example in recent years would be the debate around the value of data matching. A few states have dramatically increased their matching with third-party data sets to check the information households provide on their applications. As a general rule, this is a solid practice so long as the data sets offer relevant current information and the state has the resources to sift and sort through data matching results. But, if a state matches a household’s income and circumstances from today (when it is in need of SNAP) with income data from six months ago (when the household didn’t need SNAP), the two will not align. That does not mean that the client provided incorrect or fraudulent information on its application. More low-cost matching that just asks clients to resolve or workers to sort through bad matches appears to be a waste of time and resources that can cost much more than it saves and can divert state agency staff from more cost-effective program integrity interventions. Smart, well-timed matching, i.e., matching with higher-quality data provided via real-time access to those data while workers are talking to clients, can be extremely effective even though it might cost more in the short run.

- Will the proposal have any negative consequences, for example, would it reduce access to the program by eligible people? Earlier in my testimony, I outlined an example from the late 1990s where the program’s rules and focus on payment accuracy resulted in making it harder for eligible working-poor families to participate. Balance always has to be sought between reasonable controls and access to vital help for very vulnerable households.

- Who is promoting the change? Often private vendors selling program integrity solutions are some of the biggest critics of the program. Their self- interest in promoting problems in the program (or a perception of a program in crisis) must be considered.

We offer the following suggestions as areas that Congress might want to consider to enhance SNAP’s program integrity.

- A federal investment to allow states to upgrade their state information technology systems to ensure that caseworkers can access other government databases, i.e., Social Security, Department of Motor Vehicles, or other programs, in real time at their desks while working on adjudicating eligibility or talking to clients. All states have access to the required information, but for some it can be often on a delayed basis. This means that an eligibility caseworker might make a query and get the match back days later. That undermines their ability to work efficiently and to engage clients directly when there is a discrepancy. Federal matching funds are available to states to build this capacity, but not all have taken advantage of it. Perhaps USDA could consider procuring this tool for states.

- USDA could provide more assistance to states in assessing when errors arise because SNAP rules are out of synch with those for other major federal benefits programs, particularly Medicaid. In over 40 states, SNAP and Medicaid are co-administered. Their statutory rules, while similar, differ in some respects. Clients, caseworkers, and even state systems can confuse the requirements of one program for another. Historically, the Department of Health and Human Services and USDA have not done enough to identify these issues on their own or to engage with states on the problems and potential solutions. Many of the small vexing errors that arise as a result of these disconnects have solutions within the federal rules or within the flexibility afforded states. The federal agencies have recently started to understand their role in creating confusion across the various health and human services programs and have started to engage states on options to harmonize federal rules. They can do more.

- A joint federal-state effort to share effective methods of identifying cases that contain fraud or that are guilty of trafficking after a more in-depth investigation. This is true for both individuals and retailers. Similarly, Congress may wish to review whether USDA needs more resources or authority to remove such stores from the program more quickly.

- USDA is undertaking a review of the quality control review process based on recommendations by the Office of Inspector General. That effort may result in recommendations that require new authority or resources to enhance the quality of the system.

Not All Proposals Promoted in the Name of Program Integrity Are Effective

SNAP benefits are issued to eligible household on debit cards, commonly referred to as electronic benefit transfer (EBT) cards. Federal law provides states with the option to require a photo of one or more adult household members on the EBT. Proponents of the option claim it reduces the selling or stealing of cards because retail clerks would catch individuals using a stolen card at the checkout line. However, a recent report from the Urban Institute found that “photo EBT cards are not a cost-effective approach to combat trafficking.”[18] The Urban Institute report found that the option is costly and unnecessary. There is no evidence that requiring photos would be responsive to the issue of stolen cards; EBT cards use a Personal Identification Number (PIN), just like an ATM card, making it difficult for someone to steal the card and use it without permission. Moreover:

- Trafficking is at a record low in the program and often involves an unscrupulous retailer who is unlikely to be deterred by a photo on the EBT card.

- States have other options to improve program integrity, including procedures for replacing cards that are reported lost or stolen and EBT transaction monitoring.

- A photo EBT requirement can be costly to administer. Photo equipment must be readily accessible for all participants and EBT vendor contracts must be revised. Several states considering this policy abandoned it after comparing the costs and benefits.

The two states that have most recently implemented the option, Maine and Massachusetts, have experienced significant implementation problems that provoked intensive scrutiny from USDA. The problems in these states led USDA to propose regulations governing the option. Comments submitted by SNAP participants in Massachusetts and Maine, as well as community organizations and retailers, detail numerous examples of people confused about the policy and deterred from participating. Their concerns can be summarized as:

- Photo EBT can prevent some SNAP participants from using their benefits. While the "head of the household" is the state agency’s key contact, all household members are entitled to purchase food with SNAP benefits. In both states that have photo EBT, household members such as children, spouses, or seniors have been wrongly denied use of their cards at the grocery store checkout line because they were not the individual pictured on the card. One SNAP participant reported “a traumatic experience trying to use my family’s EBT card when shopping for food.”[19]

- Individuals with disabilities can face serious challenges with photo EBT requirements. Many SNAP participants who are unable to get to the store due to a physical condition or who require help in managing their finances due to a mental impairment often rely upon others, known as “authorized representatives,” to buy food for them. Photo EBT requirements make it harder for friends, family members, and volunteers to assist individuals with severe needs. Moreover, individuals with disabilities may not be able to go to the office, themselves, to provide a photo.

- Photo EBT proposals do not require photos of all members, leaving retailers with no way of knowing who is authorized to use the card. Retailers are not required to know all eligible users of a card and they do not have means, aside from the PIN, to ensure an individual is an authorized user of the card. This renders the photo irrelevant (albeit costly). But, some retailers or retailer staff may believe that because the photo is there that they must demand additional identification from SNAP shoppers. Such an experience can create a negative experience for customers, souring their view of a particular retailer.

- Retailers may not understand state photo EBT rules as the retailers are authorized by USDA, not the state. Retailers have not been subject to state-imposed SNAP requirements and may not know what their responsibilities are regarding photo EBT. SNAP households shop across state lines, and retailers were confused about whether one state’s limits must be imposed by retailers operating in another state.

The evidence suggests that this option does not meet any of the assessment outlined earlier in my testimony. States considering a photo EBT requirement can learn from Missouri’s earlier experience with trying a photo EBT requirement. After reviewing the state’s requirement to place a photo on EBT cards, the state auditor found the photographs useless for fraud or identification and the state wisely discontinued the policy.

Conclusion

SNAP is a highly effective anti-hunger program. Much of the program’s success is due to its entitlement structure, a consistent national benefit structure, and its food-based benefits. The program also imposes rigorous requirements on states and clients to ensure a high degree of program integrity. We look forward on working with Congress to ensure the program’s ongoing success.

End Notes

[1] For example, Bitler and Hoynes find that post-transfer poverty rate would have risen by at least one percentage point in 2010 without SNAP income, and that SNAP reduced the cyclicality of poverty during the Great Recessionary period. Nord and Prell find that food insecurity did not rise for low-income participants likely to receive SNAP as expected from late 2008 to late 2009, while it did rise for those with slightly higher incomes. Marianne Bitler and Hilary Hoynes, “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same? The Safety Net and Poverty in the Great Recession,” Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 34, Issue S1, 2016. Mark Nord and Mark Prell, “Food Security Improved Following the 2009 ARRA Increase in SNAP Benefits,” ERR-116, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, April 2011.

[2] Congressional Budget Office, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” April 2012, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/04-19-SNAP.pdf.

[3] Bitler and Hoynes, op. cit.; Peter Ganong and Jeffrey B. Liebman, “The Decline, Rebound, and Further Rise in SNAP Enrollment: Disentangling Business Cycle Fluctuations and Policy Changes,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 19363, August 2013, http://www.nber.org/papers/w19363.pdf?new_window=1; James P. Ziliak, “Why Are So Many Americans on Food Stamps?” in J. Bartfeld et al., editors, SNAP Matters: How Food Stamps Affect Health and Well Being, Stanford University Press, 2015; and Jacob Alex Klerman and Caroline Danielson, “Can the Economy Explain the Explosion in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program? An Assessment of the Local-level Approach,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 2016.

[4] Hilary W. Hoynes, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Douglas Almond, “Long Run Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net,” American Economic Review, 106(4): 903–93, April 2016.

[5] See the fiscal year 2014 error rates: http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/quality-control.

[6] For both SNAP and taxes the figures represent gross estimates (i.e., before SNAP households repay overpayments, taxpayers make voluntary late payments, or consideration of IRS enforcement activities.) The net costs are somewhat lower. See: Internal Revenue Service, “Tax Gap for Tax Year 2008-2010, Overview,” April 28, 2016, https://www.irs.gov/PUP/newsroom/tax%20gap%20estimates%20for%202008%20through%202010.pdf.

[7] SNAP State Activity Report, Fiscal Year 2014, p. 36. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/snap/2014-SNAP-Retailer-Management-Annual-Report.pdf

[8] SNAP benefits are federally funded. States and the federal government share SNAP’s administrative costs, including certifying eligibility, issuing benefits, and ensuring program integrity.

[9] The CAPER, which replaced what was known as the “negative error rate,” is separate from the underpayment error rate, which covers cases where states provided some benefits but not as much as the household should have received under SNAP rules.

[10] FNS Guide to Improving Notices of Adverse Action, http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/snap/FNS-Notice-Improvement-Guidance.pdf.

[11] The eight states are Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Guam, New Jersey, New Mexico, Nevada, and North Carolina.

[12] USDA also has a fraud hotline that the public can use to report suspected fraud to the agency.

[13] SNAP State Activity Report Fiscal Year 2014.

[14] SNAP State Activity Report Fiscal Year 2014, p. 2.

[15] U.S. Department of Agriculture, “The Extent of Trafficking in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: 2009–2011,” August 2013, http://www.fns.usda.gov/extent-trafficking-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-2009-2011-august-2013.

[16] USDA, “SNAP Retailer Management Annual Report, 2014, http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/snap/2014-SNAP-Retailer-Management-Annual-Report.pdf

[17] http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/fy2015-snap-recipient-integrity-information-technology-grant-summaries

[18] Gregory Mills, “Assessing the Merits of Photo EBT Cards in SNAP,” Urban Institute, March 2015, http://www.urban.org/publications/200159.html.

[19] Comment submitted by Vicky K. on Photo Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) Card Implementation Requirements, RIN 0584-AE45.

More from the Authors