Eliminating Estate Tax on Inherited Wealth Would Increase Deficits and Inequality

End Notes

End notes:

[1] “Statement by Robert Greenstein, President, on House Budget Chairman’s Plan,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated March 18, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=5284.

[2] CBPP estimates based on Tiffany Julian, “Work-Life Earnings by Field of Degree and Occupation for People With a Bachelor’s Degree: 2011,” U.S. Census Bureau, October 2012, http://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/acsbr11-04.pdf.

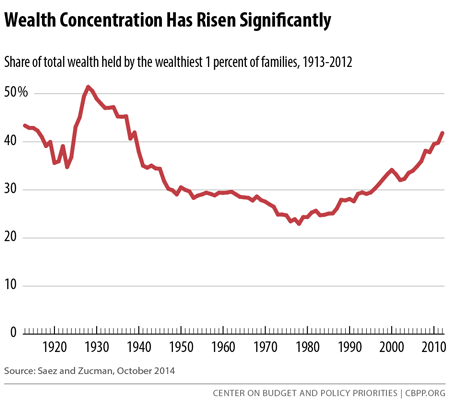

[3] Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, “Wealth Inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data,” NBER Working Paper 20625, October 2014, http://eml.berkeley.edu/~saez/saez-zucmanNBER14wealth.pdf.

[4] Lily Batchelder, “Reform Options for the Estate Tax System: Targeting Unearned Income,” testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, March 12, 2008.

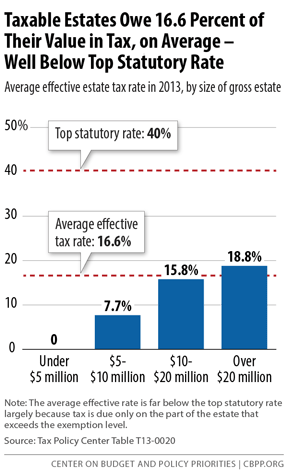

[5] Tax Policy Center Table T13-0020. The estimates have not been updated for years after 2013, but the average effective estate tax rate should be very similar for 2014 and 2015 because the statutory rate remains the same and the exemption level is indexed to inflation.

[6] Tax Policy Center Table T13-0020. TPC’s analysis defines a small-business estate as one with more than half its value in a farm or business and with the farm or business assets valued at less than $5 million.

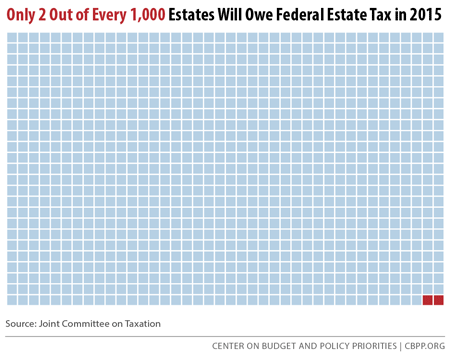

[7] Joint Committee on Taxation, JCX-68-15, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4761; CBPP calculations of added interest cost.

[8] CBPP calculations based on Joint Committee on Taxation data available at http://democrats.waysandmeans.house.gov/sites/democrats.waysandmeans.house.gov/files/documents/114-0191.pdf.

[9] See Chad Stone et al., “A Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised February 20, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3629.

[10] Emmanuel Saez, “Striking it Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States,” University of California, January 25, 2013, http://eml.berkeley.edu/~saez/saez-UStopincomes-2013.pdf.

[11] Saez and Zucman, 2014.

[12] Lily Batchelder, “Reform Options for the Estate Tax System: Targeting Unearned Income,” testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, March 12, 2008. Batchelder was a professor at New York University Law School at the time she testified; she is currently deputy director of the National Economic Council. In her testimony, she summarizes previous research, including: Thomas Piketty, “Theories of Persistent Inequality and Intergenerational Mobility,” in Handbook of Income Distribution (A. Atkinson and F. Bourguignon, eds., 1998); and Bhashkar Mazumder, “The Apple Falls Even Closer to the Tree than We Thought: New and Revised Estimates of the Intergenerational Inheritance of Earnings,” in Unequal Chances: Family Background and Economic Success (Samuel Bowles et al., eds., 2005).

[13] The President’s 2016 budget proposes to repeal this favorable treatment, also known as “step-up basis,” which would reduce the lock-in effect. In addition, the President’s budget would raise the top tax rate on capital gains to 28 percent. See Chuck Marr and Chye-Ching Huang, “President’s Capital Gains Tax Proposals Would Make Tax Code More Efficient and Fair,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 18, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=5260.

[14] Tax Policy Center Table T13-0081.

[15] Chye-Ching Huang and Chuck Marr, “Raising Today’s Low Capital Gains Tax Rates Could Promote Economic Efficiency and Fairness, While Helping Reduce Deficits,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 19, 2012, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3837.

[16] In fact, if a wealthy donor’s goal is to leave a certain amount after-tax to heirs, estate tax reduction or repeal might lead the donor to work or save less. But the research indicates that people save primarily for reasons other than to amass large estates, such as to ensure adequate income to meet all needs in old age and simply to accumulate wealth. (See Lily Batchelder and Surachai Khitatrakun, “Dead or Alive: An Investigation of the Incidence of Estate Taxes and Inheritance Taxes,” 3rd Annual Conference on Empirical Legal Studies Papers, October 28, 2008, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1134113.) Thus, repealing the estate tax would likely have only a small effect on private saving, if any.

[17] Foreign investors might increase investment in the United States, in which case more of the value of goods and services produced domestically would go towards paying foreign lenders.

[18] Jane G. Gravelle and Donald J. Marples, “Estate and Gift Taxes: Economic Issues,” Congressional Research Service, November 27, 2009.

[19] Caroline Graham, “This is not the way I'd imagined Bill Gates . . . A rare and remarkable interview with the world's second richest man,” Daily Mail, June 9, 2011, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/moslive/article-2001697/Microsofts-Bill-Gates-A-rare-remarkable-interview-worlds-second-richest-man.html.

[20] Roxanne Roberts, “Why the super-rich aren’t leaving much of their fortunes to their kids,” The Washington Post, August 10, 2014, http://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/why-the-very-rich-arent-giving-much-of-their-fortunes-to-their-kids/2014/08/10/4a9551b4-1ccc-11e4-82f9-2cd6fa8da5c4_story.html.

[21] David Joulfaian, “Inheritance and Saving,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 12569, October 2006, http://www.nber.org/papers/w12569.pdf.

[22] See Congressional Budget Office, “The Estate Tax and Charitable Giving,” July 2004; Jon Bakija and William Gale, “Effects of Estate Tax Reform on Charitable Giving,” Tax Notes, June 23, 2003; Aviva Aron-Dine, “Estate Tax Repeal — or Slashing The Estate Tax Rate — Would Substantially Reduce Charitable Giving,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 7, 2006, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=465.