- Home

- Budget Deal Is Small In Scale And Falls ...

Budget Deal Is Small in Scale and Falls Short in Some Ways, But Represents Modest Step Forward

Sharon Parrott, Richard Kogan, Joel Friedman, and Robert Greenstein

Senate Budget Committee Chair Patty Murray (D-WA) and House Budget Committee Chair Paul Ryan (R-WI) announced a small-scale budget package on Tuesday that would replace $63 billion of the sequestration cuts slated for 2014 and 2015 with alternative savings measures. The largest savings would result from continuing the sequestration cuts affecting certain entitlement programs (principally Medicare provider payments) in 2022 and 2023, instead of allowing them to expire at the end of 2021 as under current law. The package also includes higher fees for airline passengers, increased premiums for pension plans insured by the federal government, increased retirement contributions for federal civil service workers, and reduced cost-of-living increases for working-age military retirees.

The additional funding for non-defense discretionary (NDD) programs would mean that, for 2014, policymakers could discontinue a significant portion of the cuts imposed in 2013 and ease funding shortfalls in some priority areas.

The agreement falls short in some important ways, however, including the failure to extend expiring unemployment insurance benefits.

Agreement Meets Important Criteria

The agreement meets several important criteria. It would divide sequestration relief evenly between defense and non-defense discretionary programs, rejecting calls from some quarters to provide relief only or primarily for defense. It would offset the cost of providing sequestration relief without imposing cuts in key programs that would harm vulnerable children and families, seniors, and people with disabilities. It includes fees and other provisions that would increase federal revenues — although it would close no tax loopholes and would make no changes to the tax code — rather than securing all of its offsetting savings from cuts in domestic programs. And it would promote economic growth modestly by reducing sequestration cuts in the near term while the economy remains weak (although the expiration of unemployment benefits would essentially cancel out that increase in growth[1]).

It also would give appropriators an opportunity to set funding priorities as they write appropriations bills for 2014, rather than mechanically extending last year’s funding levels by funding the government through a continuing resolution.

Omissions and Downsides

The agreement’s biggest omission is, as noted, its failure to extend federal unemployment benefits for long-term unemployed workers. Lawmakers ought to remedy this in the next few days as they work on the package. Without an extension, 1.3 million workers will lose benefits just after Christmas. Unfortunately, the needs of workers who have been severely impacted by the Great Recession do not appear to be a high priority for some policymakers. House leaders have indicated that they plan to link the budget agreement to a measure to extend relief for three months for physicians from scheduled cuts in the Medicare payment rates that they receive but will not provide a similar reprieve to jobless workers.

In addition to this omission, the deal itself would replace only a modest share of the total sequestration cuts in 2014 and a much smaller share in 2015 — and provide no relief after 2015. Even under the agreement, non-defense discretionary funding would be inadequate over the next two years and beyond.

The savings in the agreement that are used for deficit reduction would barely make a dent in our longer-term fiscal challenges and would have been more usefully employed to extend emergency jobless benefits or further reduce the sequestration cuts. Both of these steps would have provided a still-needed boost to the economy.

Finally, a few of the offsets in the agreement are problematic. This includes the increase in retirement contributions for new federal workers, which could make it more difficult to recruit the high caliber federal workforce of the future that the nation needs, and the continuation of sequestration cuts in 2022 and 2023 in entitlement programs subject to sequestration.

But while the agreement has troubling omissions and limitations, it is overall a modest step in the right direction. Congress should approve it, but after making every effort to accompany it with an extension of the expiring unemployment benefits. If these benefits are not extended before the end of the year, Congress should complete this important unfinished business in early January and make the extension retroactive.

Agreement Reduces Harmful Sequestration Cuts in 2014 and 2015

The 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA) imposed austere annual caps on discretionary funding through 2021 and established the so-called “supercommittee” to develop a plan to achieve at least $1.2 trillion in additional deficit reduction. When Congress failed to enact such a plan, the annual sequestration cuts required by the BCA took effect, starting in 2013. The sequestration cuts total $109 billion each year through 2021, equally divided between defense and non-defense programs. Most of the sequestration cuts are to discretionary programs, but some entitlement programs, as well, are subject to sequestration, including payments to Medicare providers, federal unemployment benefits, and the Social Services Block Grant. About $18 billion of the $54.7 billion in non-defense sequestration cuts in 2014 would come from mandatory programs.

The agreement that Sen. Murray and Rep. Ryan reached would shrink the sequestration cuts by $45 billion in 2014 and $18 billion in 2015. Just as sequestration cuts are equally divided between defense and non-defense programs, the sequestration relief provided under the agreement also would be divided equally between defense and non-defense programs.[2]

The sequestration relief would be directed entirely to discretionary programs. The sequestration cuts imposed on mandatory programs, such as a 2 percent across-the-board cut in payments to Medicare providers and cuts in funding to states for efforts to help troubled families with children stay together, would remain fully in place. As noted, the agreement also would extend these sequestration cuts in mandatory programs for two more years, to 2022 and 2023.

The appendix provides a detailed table that shows how the agreement would affect funding for defense and non-defense discretionary programs in 2014 and 2015, and the level of sequestration cuts (both discretionary and mandatory) that would remain. In the non-defense area, the $22.4 billion in additional funding would bring total funding for non-defense discretionary programs in 2014 to $491.8 billion — an amount just slightly above the pre-sequestration funding level for 2013 (and before adjusting for inflation). In 2015, the agreement would provide only $9.2 billion in additional NDD funding, leaving total NDD funding at $492.4 billion, or about even with the 2014 funding level — and a reduction from the 2014 level once inflation is taken into account.

Until an omnibus appropriations bill is written next month, we won’t know which programs would receive a portion of the additional funding the agreement provides. Policymakers should ensure that high-priority areas that have been significantly affected by sequestration — such as Head Start and housing assistance for low-income families — receive more resources than in 2013. Last year, sequestration forced Head Start programs to serve 57,000 fewer children and reduced the number of hours that the program operates for thousands more. In addition, without additional funding, the housing voucher program will serve between 125,000 and 185,000 fewer low-income families by the end of 2014 than it served in December 2012. More adequate funding in such areas would make a large difference in the lives of many families struggling to make ends meet.

While the additional funding would be a step in the right direction, it would leave the majority of non-defense sequestration cuts in place over the two-year period, as well as all of the sequestration cuts for fiscal years 2016-2021. As discussed below, under the agreement, NDD funding in 2014 and 2015 would still be well below 2010 funding levels, even before adjusting for inflation (and farther below the 2010 level when inflation is taken into account).

On the defense side, the agreement would mean that defense funding in 2014 would be just slightly above the 2013 level after sequestration (without adjusting for inflation), rather than falling $20 billion below this level. Defense received more funding in 2013 than the BCA originally envisioned under sequestration through several one-time provisions. Because these one-time provisions don’t continue in 2014, defense is slated to be cut by $20 billion under full sequestration, relative to the 2013 level. The agreement would prevent those defense cuts.

Agreement Meets Important Criteria

The agreement meets four important criteria:

- Sequestration relief would be split evenly between defense and non-defense programs. The agreement upholds the “equity principle” from the Budget Control Act, which divided the sequestration cuts equally between defense and non-defense programs. The agreement rejects the calls from some for relief to go largely or entirely to defense programs.

- The agreement would protect vulnerable children and families, seniors, and people with disabilities from harmful cuts in basic entitlement programs. As a result, the package should not increase poverty, hardship, or inequality and likely would increase funding over the shrunken 2013 levels for discretionary programs such as Head Start that serve low-income families.

- The agreement would not eliminate any tax loopholes (or otherwise change the tax code), but it would include increases in user fees and other provisions that increase federal revenues. By including revenue-raising provisions, the agreement rejects the position taken by some that sequestration cuts must be replaced entirely by cuts in cuts in other domestic programs (primarily entitlement programs). The fee provisions in the agreement, along with the changes to military pensions, would generate enough savings to ensure that the additional funding for defense isn’t paid for by cuts in non-defense programs.

- The agreement would modestly help the economy. The agreement would reduce the sequestration cuts in 2014 and 2015, while the economy continues to recover from the Great Recession and remains well below full employment. The savings used to replace these cuts and reduce the deficit would be distributed over the next decade. This structure gets the basic economics right — shrinking the spending cuts while the economy is weaker and timing most of the offsets for when the economy is stronger. But because the package is modest, the economic impacts would be modest as well. Economist Joel Prakken, the senior managing director of Macroeconomic Advisors, commented earlier this week that a sequestration replacement package of about this size “would be a modest boost to GDP growth (relative to sequester). Maybe 1/4 percentage point.”

Moreover, because many of the offsets produce savings on a permanent basis — such as the changes in civilian and military pensions and the increased fees for airline passengers — the agreement would lower deficits in the medium and longer term, while the additional program funding it provides would be in place only in 2014 and 2015. Since our fiscal challenges are in the medium and long term while our immediate challenge is boosting the economy and job creation, this would be better-timed deficit reduction.

In addition, the agreement would provide appropriators with an opportunity to set funding priorities rather than relying on continuing resolutions to fund the government. When Congress does not reach an agreement on overall funding levels until well into the fiscal year, it often reverts to a continuing resolution (CR), which simply sets funding levels at prior-year levels (with few adjustments), rather than writing appropriations bills that more carefully establish funding levels for individual program areas.

The agreement tries to address this problem. For 2014, the agreement would give appropriators a short window to try to negotiate funding levels for program areas for the rest of the fiscal year, so that Congress can consider an omnibus appropriations bill in January. For fiscal year 2015, if Congress approves the agreement, it will have agreed upon the overall amount of funding available for appropriations bills, which should allow it to proceed under the regular process under which the appropriations subcommittees weigh funding priorities and pass individual appropriations bills.

Important Ways the Agreement Falls Short

The agreement represents a step forward but falls short in several important ways:

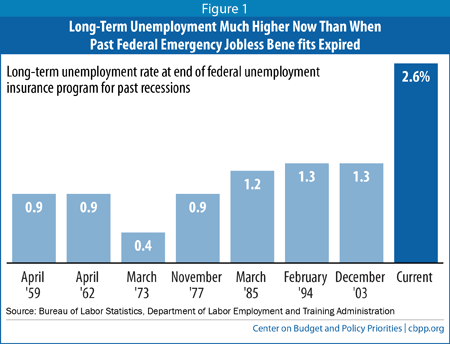

- It does not include an extension of federal Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC). If Congress does not extend EUC, 1.3 million long-term unemployed workers will lose unemployment benefits at the end of December, with another 3.5 million workers losing benefits over the course of 2014 when their state unemployment benefits run out and no federal benefits are available.[4] The overall employment picture has improved since the depths of the Great Recession, and the unemployment rate has declined to 7 percent, but much of the improvement in that measure is due to workers withdrawing from the labor force or choosing not to enter or re-enter it. This can be seen in some grim statistics: the percentage of people aged 16 and over who have jobs, which plunged when the economy turned down, has recovered little from the depths of the recession. And the long-term unemployment rate — the percentage of workers in the labor force who have been unemployed for 27 weeks or more — remains very high by historic standards. It roughly equals the highest rate ever reached in any previous recession since the end of World War II and is at least double where the long-term unemployment rate stood when all previous federal emergency unemployment insurance programs were allowed to expire. (See Figure 1.)Image

Prematurely ending EUC is harmful not only for families who lose assistance but for the economy as well. Congressional Budget Office estimates imply that if EUC is allowed to expire rather than extended, there will be up to 300,000 fewer jobs by the end of 2014 and gross domestic product (GDP) will be up to 0.3 percent lower.[5] Failing to extend jobless benefits will put a drag on the economy about as large as the Macroeconomic Advisors’ estimate of the boost provided by easing the sequestration cuts.

If Congress fails to pass an EUC extension before it goes home for the holidays, many jobless workers and their families will have a hard time paying rent starting in January. Should that happen, Congress should come back in January and promptly enact an extension retroactive to January 1.

- While NDD funding in 2014 and 2015 would be higher under the agreement, it would remain inadequate. Under the agreement, NDD funding would remain well below the already austere funding caps set in the Budget Control Act (before sequestration) and far below 2010 funding levels.

- NDD funding in 2014 would be 14.9 percent below 2010 funding levels adjusted for inflation, and 7.5 percent below the 2010 level without adjusting for inflation.

- Funding in 2015 would be even more constrained. Under the agreement, NDD funding would remain nearly flat in nominal terms between 2014 and 2015. In 2015, NDD funding would fall almost 17 percent below 2010 levels, adjusting for inflation.

- And if no future agreement is reached to reduce the sequestration cuts in 2016, NDD funding that year would again be nearly frozen at the 2015 level and be 18 percent below the 2010 level in inflation-adjusted terms.

- The provision to reduce the take-home pay of new federal civil service employees by increasing the retirement contributions withheld from their paychecks could make it harder to recruit high-quality federal workers. This cut would come on top of a several-year freeze in federal pay levels, which, along with recent furloughs and the difficulties that federal workers faced during the shutdown in October, is likely to contribute to a perception that the federal government may not be a good place to work. This could make it more difficult to recruit talented young people into federal service. As a matter of parity, the agreement takes the same amount of savings from military retirement as from federal civilian retirement contributions. The military pension system is an extremely generous one — considerably more so than that for the government’s civilian workers.

- The two-year extension of the mandatory sequestration cuts is problematic. While most of the focus on sequestration has been on the cuts to discretionary programs, sequestration also affects some entitlement and other mandatory programs. The largest cut comes from a 2 percent cut in Medicare provider payments; other affected programs include the Social Services Block Grant and a program designed to help troubled families with children stay together. According to the Congressional Budget Office, extending these cuts would take $28 billion from these programs over the 2022-2023 period; this is a key reason that the agreement would achieve $23 billion in net deficit reduction.

Some Criticisms of Agreement Are Unfounded

Some of the criticisms that have been leveled against the agreement are not valid.

- Contrary to some claims, the deal does not rely on mere promises of future budget savings that will not materialize. The offsets included in the agreement would be enacted as part of the same legislation that reduces the sequestration cuts, and these offsets would then go into effect as prescribed by law. To prevent these cuts from taking effect, policymakers would have to enact subsequent legislation to undo them, which would require approval by the House, the Senate, and the President. This would prove very difficult, especially since proponents of legislation to undo these savings would face intense political pressure to find equivalent alternative savings.

- The fact that the agreement is small-scale does not make it bad policy. Sen. Murray and Rep. Ryan have made clear their goal was a practical, short-term agreement that would undo some of the problematic sequestration cuts, and that is what they have crafted. We do not have a short-term deficit crisis that needs immediate attention — many economists think the deficit has fallen too rapidly in recent years, creating a drag on an economy that still isn’t producing enough jobs more than four years after the end of the Great Recession. Policymakers ultimately will need to take action beyond the scope of this agreement to address our longer-term fiscal challenges, but such action isn’t needed immediately, and the sequestration cuts are causing harm right now.

Conclusion

The agreement is modest, but the additional funding would mean that important programs could be funded more adequately in 2014 and 2015 than would otherwise be the case. A side benefit is that Congress is showing it can work across party lines to address some problems (even if only in a modest, partial way).

The most disappointing part of the agreement is what it doesn’t include: the extension of Emergency Unemployment Compensation. Before members of Congress go home to celebrate the holidays, they should extend these important benefits so unemployed workers can pay rent and put food on the table as they, too, usher in the new year. If Congress fails to perform this basic task, it is critical that when it returns to Washington in January, lawmakers take up this unfinished business and do the right thing for these workers and the economy.

Appendix: The Deal by the Numbers

The table below shows how sequestration affects defense and non-defense discretionary and mandatory programs under current law and how the agreement would change sequestration and funding levels.

Failure to Extend Emergency Unemployment Benefits Will Hurt Jobless Workers in Every State

End Notes

[1] Chad Stone, “Failure to Continue Jobless Benefits Would Undo Budget Deal’s Economic Boost,” Off the Charts, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 11, 2013, http://www.offthechartsblog.org/failure-to-continue-jobless-benefits-would-undo-budget-deals-economic-boost/.

[2] The agreement reduces the sequestration cuts required by the BCA by equal amounts. Some of the offsets in the package may effectively reduce the amount of funding restored to non-defense discretionary programs, but only modestly.

[3] Ezra Klein and Evan Soltas, “Wonkbook: The ‘Grand Bargain’ Is Over,” Wonkblog, Washington Post, December 9, 2013, http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/12/09/wonkbook-the-grand-bargain-is-over/.

[4] Chad Stone, “Failure to Extend Emergency Unemployment Benefits Will Hurt Jobless Workers in Every State,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 11, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=4060.

[5] Congressional Budget Office, “How Extending Certain Unemployment Benefits Would Affect Output and Employment in 2014,” December 2013.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise