Over a million unemployed Americans who have been looking for work for at least six months will receive no further federal jobless benefits after Christmas week if Congress does not renew the Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) program, which expires at the end of the year. Many more who lost their jobs more recently or will lose them in coming months will get no additional help in 2014 beyond their regular state-funded jobless benefits.

EUC, like the federal emergency unemployment insurance (UI) programs enacted in every major recession since 1958, is a temporary program that provides additional weeks of UI to qualifying jobless workers during periods when jobs are hard to find. Emergency federal UI not only helps relieve hardship among those jobseekers and their families; it is also widely recognized as one of the most cost-effective ways to increase demand and spur job creation in a weak economy. Both of those tasks — relieving hardship and boosting the economy — remain necessary today.

Opponents of extending EUC claim that the program is too big and has lasted too long.[1] To be sure, it has lasted a lot longer, helped a lot more unemployed workers, and paid out substantially more in benefits than the programs enacted in past recessions. But this is because the blow to the economy and especially the labor market from the Great Recession was so much worse. In fact, without the consumer spending that UI generated, the recession would have been even deeper and the recovery even slower, according to mainstream economic analysis.[2]

Although the economy has been expanding for over four years, unemployment remains much too high, especially among those who have been looking for a job for six months or more:

- The unemployment rate, currently 7.3 percent, remains over two percentage points higher than when the recession started in December 2007.

- The labor force participation rate (the percentage of the population aged 16 and over either working or actively looking for work) has continued to decline even as the unemployment rate has come down, reaching levels last seen in 1978 when many fewer women were in the paid labor force.

- As a result of high unemployment and a falling labor force participation rate, the percentage of the population aged 16 and over with a job fell sharply in the recession and is barely higher today than it was when the recession hit bottom.

- Long-term unemployment remains much worse than in previous recessions. The percentage of the labor force unemployed for 27 weeks or more hit record highs in the recession and is still twice as high as it was when the last three federal emergency UI programs expired. Some 4.1 million of the nation’s 11.3 million unemployed workers have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. That’s longer than the maximum number of weeks of regular state-funded UI in all but two states.

In addition, the premature turn towards budget austerity since 2010 has been a drag on economic growth and job creation. Extending EUC would help offset that drag as well as reduce hardship among jobless workers and their families. In contrast, letting EUC expire would increase hardship and cost the economy jobs.

The federal-state UI system assists workers who have lost their jobs through no fault of their own by temporarily replacing part of their lost wages.[3] In most states, the maximum duration of these regular state benefits is 26 weeks, though a handful of states have shortened it recently.[4] UI benefits have averaged about $300 per week in recent years.[5]

In normal economic times, most people find a job in less than six months. But in a recession, when jobs become scarce, the number of people experiencing longer spells of unemployment grows. Income losses from unemployment drain purchasing power from the economy, making an economic downturn worse and the recovery from it weaker.

To combat the increased hardship and economic drag from rising unemployment and longer unemployment spells, policymakers in every recession starting in 1958 have created a temporary federal UI program to provide additional weeks of benefits to jobless workers who exhaust their regular, state-funded UI benefits before they can find a job. Policymakers enacted the current program, Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC), in June 2008, relatively early in the

Great Recession. They raised the number of weeks of federal emergency benefits as the Great Recession worsened in late 2008 and 2009, and they extended the program several times as the economy has struggled to restore the labor market to normal health.

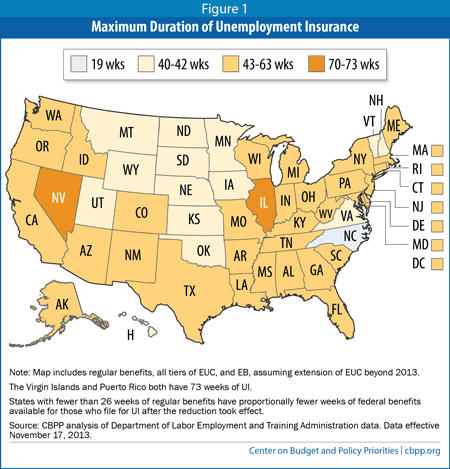

At one point, the maximum number of weeks of UI available in states with very high unemployment rates was 99 weeks (counting the 26 weeks of regular state benefits). That maximum number is now 73 weeks, and the number is lower than that in in all but two states; the number of weeks of benefits depends on a state’s unemployment rate and is lower than it has been over the past few years, partly as a result of legislation enacted in February 2012 that scaled the program back (see Figure 1).[6] EUC is scheduled to expire at the end of the year. Payments will stop for current EUC recipients the week after Christmas, and no new claims for EUC benefits will be accepted.

The National Employment Law Project (NELP) estimates that over 2 million people will lose out on jobless benefits by the end of March 2014 if EUC is not reauthorized.[7] First, the estimated 1.3 million workers currently receiving payments will be cut off immediately at the end of December. Then, over the course of January, February, and March, an estimated 850,000 more people will run out of regular state UI benefits and will receive no further help.

Labor Market Remains Much Weaker Than in Other Recent Recoveries

The unemployment rate rose sharply in late 2008 and early 2009, and although it has come down from its high of 10.0 percent in October 2009, the current rate of 7.3 percent in October 2013 is still well above pre-recession levels.[8] Policymakers have never allowed an emergency federal UI program to expire with the labor market as weak as it is today. While unemployment is now in the 7.0 to 7.5 percent range, many analysts, including Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, have emphasized that the unemployment rate overstates improvements in the labor market since the Great Recession.[9]

Table 1

Unemployment, Long-Term Unemployment (27 Weeks or Longer), and Temporary Federal Unemployment Insurance Programs in Recent Recessions |

| | 1981-82 Recession | 1990-91 Recession | 2001 Recession | 2007-2009 Recession |

| Recession months | July 1981 to

Nov. 1982 | July 1990 to

March 1991 | March to

Nov. 2001 | Dec. 2007 to

June 2009 |

Months of temporary

federal unemployment

program (for new

claimants) | Sep, 1982 to

March 1985 | Nov. 1991 to

Feb. 1994 | March 2002

to Dec. 2003 | July 2008

to present |

Unemployment rate at

start of recession | 7.2 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 5.0 |

Unemployment rate at

end of program for new

claimants, if current

program expires at end

of 2013 | 7.2 | 6.6 | 5.7 | About 7.2 |

Long-term

unemployment rate at

start of recession | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

Peak long-term

unemployment rate | 2.6 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 4.3 |

Long-term

unemployment rate at

end of program, if

current program expires

at end of 2013 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | About 2.6 |

| Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration, National Bureau of Economic Research |

- The unemployment rate remains more than two percentage points higher than the 5.0 percent unemployment rate at the start of the recession in December 2007. (See Table1.) The highest unemployment rate at which federal UI has previously been allowed to expire was 7.2 percent in March 1985, when the program enacted in the 1981-82 recession enrolled its last claimants. But in that recovery, unlike the current one, 7.2 percent represented a return to the unemployment rate at the start of the recession. Moreover, the unemployment rate has farther to fall now to restore high levels of employment than it did then.[10]

-

The labor force participation rate (the percentage of the population aged 16 and over either working or actively looking for work) has continued to decline even as the unemployment rate has come down. Put another way, the decline in the unemployment rate has not been accompanied by the re-entry of people into the labor force that typically occurs in a robust economic recovery. Part of this reflects demographics, as more and more baby boomers retire. But a similar though somewhat smaller decline is evident in labor force participation among the prime working-age population, aged 25-54.

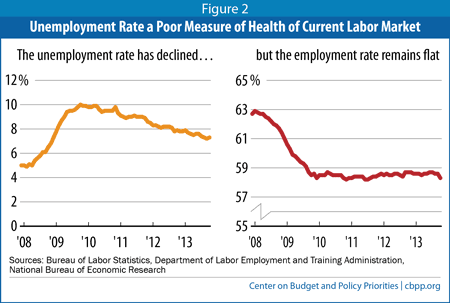

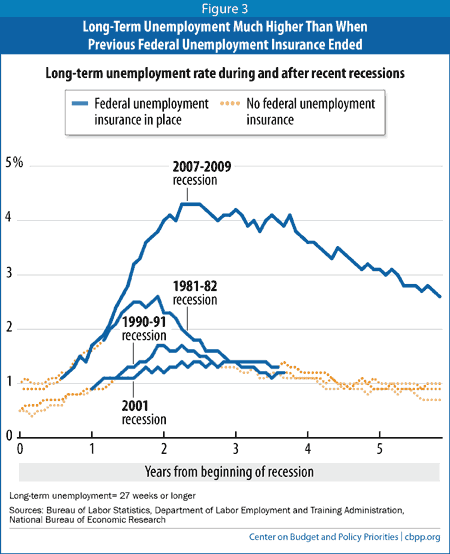

The sharp increase in unemployment early in the Great Recession drove down the employment-population ratio (also known as the employment rate) — the percentage of the population aged 16 and over with a job. The ongoing decline in labor force participation has kept the employment rate from rebounding as the unemployment rate has come down. As Figure 2 shows, the employment rate fell sharply when the recession hit, but has barely improved since the recession hit bottom.[11] - Most significantly, long-term unemployment has been much worse than in previous recessions. The long-term unemployment rate — the percentage of people in the labor force who have been unemployed for 27 weeks or more — hit record highs as a result of the Great Recession. While it has come down some in recent years, it now roughly equals the highest rate reached in any previous recession since the end of World War II (2.6 percent in June 1983). And, as Figure 3 shows, the current rate is dramatically higher than it was when all previous federal emergency UI programs expired.

Opponents of continuing emergency UI benefits often assert that UI discourages people from looking for work and that ending these benefits would speed a return to full employment. Though research from earlier periods showed that additional weeks of unemployment insurance have an impact in lengthening unemployment spells, most careful recent research indicates that these concerns are seriously overblown, especially in the current jobs slump.

Additional weeks of UI benefits have three distinct effects on the duration of unemployment spells. First, unemployment insurance allows a financially strapped unemployed worker to search more efficiently for an appropriate job rather than having to accept the first job offered, whether or not it is a good match for his or her skills. Second, since unemployed workers must look for work in order to qualify for UI benefits, additional weeks of UI benefits keep unemployed workers attached to the labor force and looking for jobs for longer than they might otherwise. Finally, UI creates minor disincentives to look hard for a job by providing ongoing financial support, albeit at only half or less of the worker’s former salary.

One study released in early 2010 offers a “back of the envelope calculation,” based on the relevant research, that the weeks of benefits added through EUC could account for “between 0.7 and 1.8 percentage points of the 5.5-percentage-point rise in the unemployment rate [from its pre-recession low].” But it also noted that “the true effect of extended UI benefits on unemployment duration is likely to be at the lower end of these estimates.”[12]

Indeed, a careful study of recent evidence by Jesse Rothstein, former chief economist at the Labor Department, found that federal extensions of UI in the Great Recession likely had an even smaller effect than this. Rothstein found that the unemployment rate in December 2010 would have been about 0.2 percentage points lower without the extension of unemployment compensation.[13] Rothstein also found that at least half of this 0.2 percentage-point increase could reflect greater labor force attachment; in other words, the availability of extended UI benefits kept some jobless workers actively searching for work who otherwise would have stopped searching and dropped out of the labor force. Most other studies of the disincentive effect of UI in the current downturn have also found relatively small effects.

Harvard economist Lawrence Katz, a leading expert on U.S. labor markets, has also observed that traditional estimates of the relationship between UI and the length of unemployment spells ignore other effects, such as “the macroeconomic stimulus impacts of increased consumption expenditures by the unemployed … as well as the gains from keeping more of the long-term unemployed attached to the labor market rather than moving onto disability programs.”[14]

Proponents of ending EUC nevertheless continue to argue that the disincentives to look for work are large, and they are now touting a study they say identifies EUC as the “cause” of the painfully slow labor market recovery.[15] The study, by University of Oslo economist Marcus Hagedorn and three colleagues, contains statistical estimates of the relationship between UI and unemployment that the authors say “imply” that the expansions in UI could have been responsible for most of the rise in unemployment in the Great Recession.[16] But the Hagedorn study does not directly test the proposition that EUC caused the rise in unemployment or rule out other plausible explanations.

Moreover, contrary to the view of conservative critics of EUC, the Hagedorn study does not claim that EUC discourages unemployed workers from looking for jobs — it accepts the findings of studies like those cited above that this effect is very small. The study focuses instead on employers’ decisions to create jobs. Its premise is that employers expect that the additional weeks of UI provided by EUC will raise their hiring costs and cut into their profits, so they make fewer job offers. In this model, UI raises hiring costs because only higher wages will “lure” unemployed workers off UI.

While the Hagedorn study’s findings are interesting, they rest on a model of the job market that many economists would regard as ill-suited to deal with major unemployment shocks like the Great Recession. The more plausible mainstream explanation for why unemployment is so high is that businesses still don’t have enough sales to justify hiring enough workers to restore normal levels of employment.

In summary, arguments that emergency UI benefits are an important contributor to today’s high unemployment have cause and effect backwards. We have a temporary federal program because unemployment is so high and jobs are so hard to find. When there are three unemployed workers for every job opening, it is hard to see how sharply curtailing the duration of UI benefits would promote job creation. Rather, EUC benefits help create that additional demand and contribute to job creation.

The problem for most businesses in an economic slump is not that they don’t have enough capacity to meet existing demand but that they don’t have enough demand for their goods and services to fully utilize their existing capacity. Thus, policies that put customers in the stores with money to spend will likely be more successful at closing the output gap and creating jobs than giving businesses tax breaks.

As the Congressional Budget Office has explained, unemployment insurance “adds to overall demand and raises employment over what it otherwise would have been during periods of economic weakness.”[17] UI benefits are targeted on workers who are involuntarily unemployed and whose income has fallen, a group that tends to be concentrated in the areas and industries most affected by a slowdown. Supporting spending by unemployed workers in hard-pressed communities helps prevent the spread of layoffs and job losses in those communities. The assistance provided by EUC will be especially important for low-income unemployed workers in light of the recent reductions in SNAP (food stamp) benefits and proposed further cuts.[18]

This is why CBO consistently ranks assistance for unemployed workers, along with SNAP benefits and refundable tax credits for low-income households, as one of the most effective policies for generating economic growth and creating jobs. Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Analytics, estimates that each dollar of UI benefits generates $1.55 in new economic activity in the first year.[19]

Failure to extend the federal unemployment programs would mean less spending by unemployed workers and their families, which would hurt sales at local businesses and undermine job creation in an already weak recovery. Effective temporary stimulus measures like emergency UI benefits can give the economic recovery a much needed boost and reduce the risk of sliding back into recession.

The Economic Policy Institute (EPI) recently estimated that it would cost about $25.2 billion to continue EUC through 2014. Using “bang-for-the-buck” estimates similar to those of CBO and Zandi, EPI estimates that failing to extend the program would cost the economy $37.8 billion of spending and 310,000 jobs.[20]

Continuing EUC would also help offset the drag on economic growth and job creation created by sequestration and earlier budget cuts. Zandi finds that, “The economic drag from fiscal austerity is greater than at any time since just after World War II.” The economic forecasting firm Macroeconomic Advisers estimates that the spending contraction since 2010 has raised the unemployment rate by 0.8 percentage point — the equivalent of 1.2 million lost jobs.[21]

Policymakers can reduce that drag by replacing sequestration with back-loaded deficit-reduction measures that don’t begin to take effect until the economy is stronger.[22] They can provide a further needed boost by renewing EUC for another year.