- Home

- Four Timing Gimmicks That Could Disguise...

Four Timing Gimmicks That Could Disguise Fiscally Irresponsible Individual Tax Reform

A key goal of tax reform should be to generate revenue to help reduce long-term deficits. Policymakers should not undermine this goal by using budget gimmicks to exaggerate the savings from a proposed tax-reform package or, worse, as cover for tax “reforms” that expand deficits.

Like corporate tax reform,[1] individual tax reform is vulnerable to timing gimmicks. Tax reform will require policymakers to make difficult choices, particularly when it comes to paring back tax expenditures (tax deductions, exclusions, and other tax breaks) to offset the cost of the substantial rate cuts that some tax reform advocates seek.[2] Many of these tax expenditures — such as the mortgage interest deduction and charitable deduction — are widely used and popular. If given a choice, policymakers may find it attractive to rely on imaginary savings from budget maneuvers, rather than to rely entirely on limiting popular tax breaks. They have used this approach before to enact regressive, deficit-increasing tax cuts.

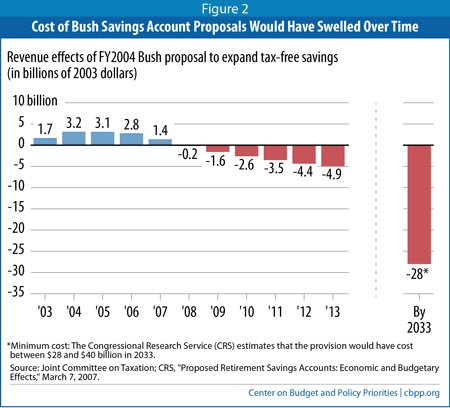

Four common timing gimmicks that could conceal fiscally irresponsible individual income tax reform are:

-

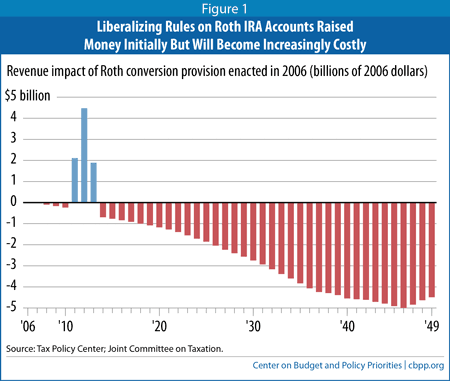

Treating as tax increases changes that raise revenues initially but lose as much or more revenues later. Expansions of tax incentives increase deficits over the long term. But within the ten-year “budget window” used to estimate the official cost of legislation, some of these expansions — particularly those related to “Roth” retirement savings accounts — can actually raise money, as taxpayers pay taxes up front in lieu of paying higher taxes later. Policymakers can then use the revenue that this gimmick produces over the first ten years to “pay for” additional deficit-widening tax cuts.

For example, in 2006 Congress liberalized the rules regarding Roth accounts. The provision in question raised $6.4 billion in the initial decade, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT). But it expanded deficits by over $12 billion in the second decade, and by another $30 billion in the decade after that, according to the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.[3] Congress used the temporary revenue gain to help “pay for” other tax cuts in the 2006 legislation, such as an extension of dividend and capital gains tax cuts.

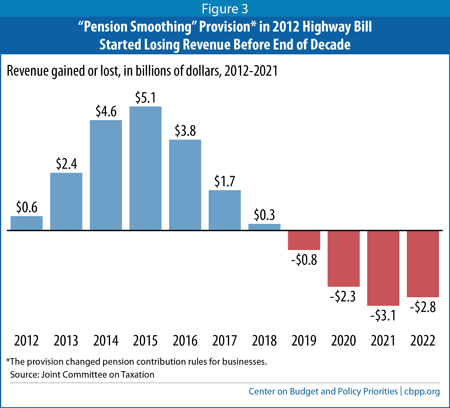

With other timing gimmicks, the long-term revenue loss can roughly match (rather than exceed) the short-term revenue gain, but such changes still can’t “pay for” anything. For example, in recent weeks, some policymakers have proposed repealing health reform’s medical device tax and offsetting the cost by expanding a provision enacted in 2012 that changes how much companies must contribute to their employees’ pension funds. The proposed change in the pension contribution rules would raise revenues initially (for reasons explained below), but those gains would be offset by roughly equal revenue losses in later years, outside the budget window. If coupled with a permanent repeal of the medical device tax, such a package would raise deficits by billions of dollars in the long run.

-

Ignoring the fact that the revenue gains from some tax changes shrink over time. Some tax changes produce much larger savings in the initial decade than in later decades. This occurs when tax expenditures that effectively allow filers to delay paying tax are reversed; this has the effect of bringing tax payments forward but reducing revenue in later years. If policymakers use revenues that only occur within the first decade to “pay for” other provisions whose costs are permanent and grow over time, the result will be a net revenue loss over the long term.

For example, the 1986 tax-reform law financed rate cuts with base broadening, but as Georgetown University tax law professor and former JCT chief of staff John Buckley has explained, “The 1986 tax reform was financed to a very large extent by timing changes. . . . And the [law’s] rate reductions lasted a grand total of four years before they had to be reversed because the one-time tax increases from those timing changes were no longer there.”[4]

-

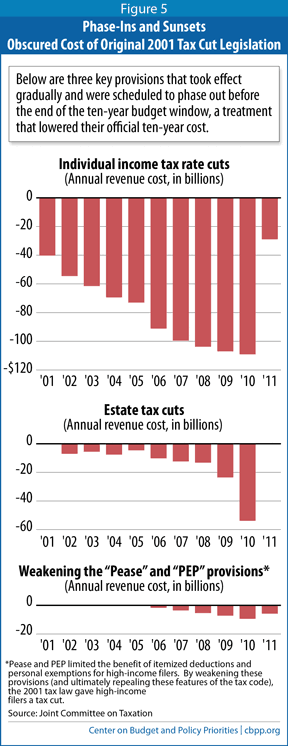

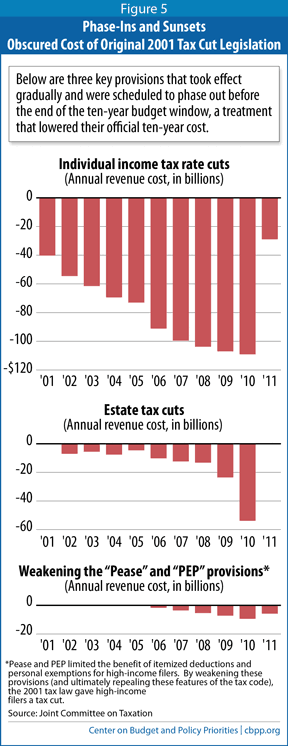

Phasing in costly provisions so their full cost doesn’t show up in the ten-year budget window. In 2001, for example, Congress enacted two income tax cuts for high-income filers — the gradual elimination of the so-called “Pease” and “PEP” provisions — but designed these tax cuts so they didn’t start taking effect until 2006 and didn’t take full effect until 2010. Indeed, their cost rose from $1.3 billion in 2006 to $9.4 billion in 2010. If a tax cut doesn’t take full effect until part-way through the initial decade, its cost over that decade will give a misleading impression of its cost in future decades.

-

“Sunsetting” costly provisions that Congress intends to extend permanently. For example, Congress designed most of the tax cuts enacted in 2001 to expire at the end of 2010, one year before the end of the ten-year budget window, in order to fit more tax cuts into the agreed-upon target for the ten-year cost of the tax cuts. Congress later extended nearly all of these tax cuts without paying for them.

Tax reform should generate revenues to help meet the nation’s long-run fiscal challenges. This means the revenue savings from tax reform should be real and lasting, not an illusion caused by timing gimmicks. To prevent the use of timing gimmicks, policymakers should hold tax reform to a fiscal standard that extends beyond the first decade.

Possible Timing Gimmicks

Congress’ official tax scorekeeper, the Joint Committee on Taxation, typically evaluates the revenue effects of tax proposals over ten years. Policymakers can try to take advantage of this budget window by hiding the true costs of tax measures outside the first ten years, so that a tax bill that meets its revenue target (and congressional budget rules) in the first ten years may fail to do so in later decades. Such maneuvers include:

Treating as Tax Increases Changes that Raise Revenues Initially But Lose Revenues Later

One of the more egregious timing gimmicks is to treat a permanent tax cut that raises revenue in the initial years as though it were a tax increase, using the temporary revenue to “pay for” other permanent tax cuts. Tax breaks for retirement saving particularly lend themselves to this approach.

The tax code offers two basic types of retirement incentives:

- “Front-loaded”: Taxpayers do not pay income tax on their contributions to some tax-preferred retirement accounts, such as 401(k)s and 403(b)s and conventional IRAs. Withdrawals from these accounts in retirement then are fully taxable.

- “Back-loaded”: Contributions to Roth individual retirement accounts (IRAs) and Roth 401(k)s are taxed upfront. Withdrawals in retirement (including the earnings on those contributions) are then tax free.

Taxpayers choose the type of retirement vehicle that benefits them most over time.

Policymakers have exploited this timing difference to treat certain tax cuts as tax increases. By making it easier to contribute to Roth-type accounts or making the tax breaks for these accounts even more generous, policymakers can encourage taxpayers to use these Roth accounts, including converting existing 401(k)-type accounts into Roth accounts. These changes temporarily boost tax revenues, as filers choose to pay more tax upfront in order to enjoy tax cuts in later years (which correspondingly reduce tax revenues in later decades). Policymakers then can use the revenue bumps inside the budget window to “pay for” other tax cuts, as though the retirement changes were actually a tax increase, even though they will add to long-run deficits.

A tax package enacted in 2006, for example, significantly liberalized taxpayers’ ability to contribute to Roth IRAs.[5] JCT estimated that this provision would raise $6.4 billion in the initial decade as filers paid upfront taxes in order to convert their conventional IRA accounts to Roth IRA accounts. This temporary revenue increase helped lower the official ten-year cost of the package (which, among other things, extended low tax rates on capital gains and dividend income) and thereby avoid triggering a Senate budget rule that would have required 60 votes to override. But estimates from the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (TPC) indicate the provision would expand deficits by over

Even in “net present value terms” — that is, under a standard that fiscal policy analysts use that assumes a dollar of tax revenue received today is worth more than a dollar received a number of years from now — the provision would add to deficits over 40 years, TPC estimates showed. The Congressional Research Service reported that the provision “from a budgetary standpoint simply speeds up tax payments, causing revenue gains today and a loss, with interest, in the future.”[7]

Another example of the use of such timing gimmicks occurred when the American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA, the bill embodying this year’s cliff deal) was enacted in early 2013. ATRA reduced sequestration by $24 billion for 2013 and “offset” half of the cost by making it easier for individuals to shift large sums from 401(k)s, 403(b)s, and the like into a Roth account. Taxpayers would have to pay tax up front on the amounts they shifted, but all subsequent earnings in the Roth accounts — and all withdrawals in later years — would be tax free.

The provision will raise about $12 billion in the early years as people making the shift paid taxes on the amounts they moved to the Roth accounts. But this temporary gain ignores the long-run deficit increase that would result. As the Wall Street Journal put it, “In effect, the move provides more up-front revenue to the Treasury, but potentially at the cost of revenue over the long term — as taxes paid when individuals make withdrawals from their 401(k) plans would likely be far greater.”[8] As Joe Rosenberg of TPC said, the provision is a “way to game revenue in the [budget] window.”[9]

Various other tax changes are almost wholly timing shifts: they increase revenues up front, but all of that increase represents reduced tax collections in later years. Even when such timing shifts are roughly revenue-neutral over a long period (rather than resulting in net revenue losses over time), they cannot “pay for” anything, because they produce no net budgetary savings. Nevertheless, because such timing shifts look like a tax increase within the budget window, policymakers can be tempted to use them to “offset” the cost of other tax cuts or spending increases, which is a recipe for making long-run deficits worse.

For example, a provision enacted in 2012 to help “finance” highway infrastructure spending allowed employers to “smooth out” their contributions to their employees’ pension funds by contributing less in the short and medium term and more in the longer term. These contributions are tax-deductible, so shrinking them raises employers’ income tax payments — and thus overall federal tax revenues — for the first few years. But in later years, employers will contribute more and take higher tax deductions, so they will pay less income tax than under the previous rules.

Some policymakers are now proposing to expand the 2012 “pension smoothing” provision in order to help offset the cost of repealing the medical device tax enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act. Doing so would produce a similar pattern of short-term revenue gains, but as with the 2012 provision, those gains would be offset by lower revenues outside the budget window. If coupled with permanent repeal of the medical device tax, such a package would raise deficits by billions of dollars each year over the long run.[13]

Ignoring the Decline Over Time in Savings from Some Tax Changes

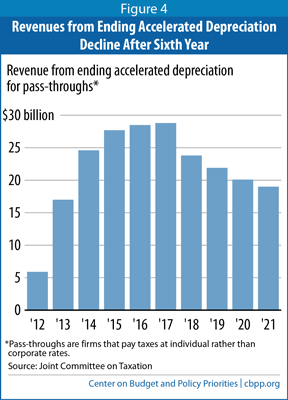

Repealing or limiting certain types of tax expenditures will raise revenues by larger amounts in the first decade than in any subsequent decade. This occurs when tax expenditures that effectively allow filers to delay paying tax are reversed, bringing tax payments forward to earlier years but reducing them in later years. (Such changes often continue to deliver revenue increases in the out years, but not at the same level as in the first ten years.)

For example, the largest single tax break for businesses is accelerated depreciation, which allows firms to deduct over time the cost of investments (such as new equipment) more quickly than those assets actually lose value.[14] JCT estimates that the annual revenue savings from ending accelerated depreciation for “pass-throughs” — businesses that choose not to incorporate and pay corporate income tax on their profits but instead pass the profits through to their owners, who pay taxes at individual income tax rates — would peak within the ten-year budget window but then fall by about a third by the end of the window (see Figure 4). Analysis by Treasury officials shows that the savings would continue to decline in the long run.[15]

Phasing in Costly Provisions to Obscure Their Long-Term Cost

Policymakers can gradually phase in costly provisions of a tax-reform package, such as rate cuts, so that their permanent cost doesn’t become clear until after the ten-year budget window. Even provisions that phase in completely within the first ten years can mislead the media and public because their cost will be much larger in later decades, once the provisions are fully effective, than in the initial decade.

To keep down the ten-year cost of the 2001 Bush tax cuts, for example, policymakers phased some of them in gradually over the budget window. Two such provisions included the gradual repeal of “Pease” and “PEP,” which limited the deductions and exemptions that high-income filers can claim; policymakers first enacted Pease and PEP as part of 1990 bipartisan deficit-reduction legislation.[16] The 2001 tax-cut bill phased out Pease and PEP starting in 2006 — more than halfway through the budget window — culminating in full repeal in 2010. This provision cost nothing for five years, then $1.3 billion in fiscal year 2006 and grew to $9.4 billion in fiscal year 2010, according to JCT (see Figure 5).

The Bush tax cuts also phased in regressive cuts to the estate tax over 2002-2010, ending in full repeal in 2010. JCT estimated that the annual cost of the estate tax cuts jumped from less than $1 billion in 2001 to $54 billion by 2010 (see Figure 5).

Still another example involved the provision of the Bush tax cuts that increased the Child Tax Credit from $500 per child to $1,000. The credit didn’t reach $1,000 until 2010.

Image

“Sunsetting” Costly Provisions That Congress Plans to Extend Permanently

“Sunsetting” Costly Provisions That Congress Plans to Extend Permanently

Policymakers can lower the official cost of rate cuts or new tax expenditures by putting artificial sunsets (expiration dates) on them, even if they fully intend to extend the tax cuts indefinitely without paying for them.

Most of the tax cuts enacted in 2001 were set to expire at the end of 2010, one year before the end of the ten-year budget window. That early sunset artificially reduced the ten-year cost of the tax cuts, allowing the legislation to comply with a budget resolution that capped the cost of the tax cuts over the initial decade. (See Figure 5.) The sunset provision also allowed the tax cuts to get around a congressional rule designed to prevent certain budget legislation from increasing deficits outside the budget window.

Thus, the 2001 tax-cut package used both sunsets and phase-ins. In the words of then-House Ways and Means Chairman Bill Thomas, these sunsets, phase-ins, and other gimmicks in the law allowed Congress to put “a pound and a half of sugar into a one-pound bag.”[17]

Proponents of the tax cuts always intended to make them permanent before the sunsets took effect. As Dan Bartlett, President Bush’s communications director, said, “We knew that, politically, once you get it into law, it becomes almost impossible to remove it. . . . The fact that we were able to lay the trap does feel pretty good, to tell you the truth.”[18] Ultimately, policymakers didn’t allow the sunsets to take effect. They extended all of the Bush tax cuts in 2010 without paying for them, and the “fiscal cliff” deal at the beginning of 2013 made 82 percent of them permanent — again without paying for them — at the beginning of 2013.[19]

Ensuring That Tax Reform Is Fiscally Responsible in the Long Run

The nation’s fiscal problems are long term in nature, driven by the imbalance between revenues and expenditures (especially as expenditures are pushed up by the aging of the population and increases in health care costs throughout the U.S. health care system). Accordingly, policymakers should hold tax reform to a fiscal standard that extends beyond the first decade. Otherwise, previous experience shows it is all too easy for them to use timing gimmicks to enact tax changes that worsen long-term deficits. (Similarly, if policymakers use gimmicks to inflate the revenue contribution to a deficit-reduction package that also cuts entitlement spending, the deal will not be balanced in the long run.)

There is recent precedent for taking these longer-term considerations into account. Congressional Democrats and the White House revised the health reform bill at the end of the legislative process in early 2010 precisely to ensure that it would reduce the deficit in the second ten years as well as the first ten, under Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates. In addition, the Senate’s “Gang of 8” designed the immigration bill that the Senate passed in June 2013 so that CBO would find that the bill would reduce deficits in the second decade as well as the first.

In the same vein, the President’s proposed framework for business tax reform would avoid timing gimmicks by not using temporary revenue increases from repealing or limiting business tax expenditures to “pay for” permanent corporate rate cuts. Instead, the Administration’s framework proposes to use temporary revenues only to fund one-time investments (in jobs and infrastructure). Rate cuts would be constrained so that their cost equals the savings from permanent revenue increases.

Policymakers should note, however, that even analyses of tax reform costs in the second decade have some limitations. The full out-year revenue loss from some timing shifts, such as some changes in the tax treatment of retirement savings may not fully show up until subsequent decades when more of the taxpayers taking advantage of these provisions retire.

As noted above, some tax expenditure reforms are worth doing regardless of whether they raise less money after the first decade. But policymakers should take this front-loaded revenue pattern into account and not use it to produce tax reform that hits its revenue targets only in the short term and not over the long run, as well.

Timing Gimmicks Can Also Disguise Tax Changes’ Regressive Impact

Timing gimmicks can be used to hide tax reform’s long-run impact not only on revenues and deficits, as this paper explains, but also on the progressivity of the tax system.

For example, if a tax reform package included cuts in top tax rates or other regressive tax cuts that took full effect only after ten years, it would be more progressive inside the budget window than in later years. In addition, some changes to business tax expenditures can raise more revenue inside the budget window than in later decades. Because these tax expenditures primarily benefit high-income filers, such changes will appear more progressive inside the budget window than outside it.

Another example concerns Roth-type retirement savings accounts. Over the long term, expanding the tax breaks for these accounts is a regressive tax cut because it disproportionately benefits affluent filers, who can afford to set aside more funds in the accounts. But inside the budget window, such a change can appear to be a progressive tax increase, because high-income filers would pay more tax in the short term as they move assets from other retirement savings vehicles into Roth-type accounts. Distributional analyses (that is, analyses of how a given policy change would affect people in different income groups) could choose to ignore such high-income “tax increases” because they are temporary. But ignoring these changes and leaving them out of distributional analyses would effectively treat such tax changes as being distributionally neutral, when they would likely be regressive in the long run.

Analyses of the distributional effects of tax reform in the first decade can therefore give a distorted picture of how the proposed changes would affect after-tax income inequality over a longer period. Just as policymakers should hold tax reform to a fiscal standard that looks beyond the first decade, they also should hold tax reform to a distributional standard that looks beyond the budget window.

Tax Expenditure Reform: An Essential Ingredient of Needed Deficit Reduction

Proposed Offset for Medical Device Tax Can’t Offset Anything — It’s a Timing Gimmick

End Notes

[1] Chye-Ching Huang, Chuck Marr, and Nathaniel Frentz, “Timing Gimmicks Pose Threat to Fiscally Responsible Tax Reform,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 24, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3994.

[2] Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, and Joel Friedman, “Tax Expenditure Reform: An Essential Ingredient of Needed Deficit Reduction,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 27, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3912.

[3] Leonard E. Burman, “Roth Conversions as Revenue Raisers: Smoke and Mirrors,” Tax Policy Center, May 11, 2006, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/url.cfm?ID=1000990.

[4] Tax Analysts Roundtable Discussion on Taxes and Small Business, Washington, D.C. Friday, January 20, 2012.

[5] It eliminated the provision barring filers with incomes over $100,000 from converting their front-loaded tax-deductible IRA plans into Roth IRAs. It also effectively eliminated income limits on contributions to Roth IRAs for people under age 70½.

[6] Leonard E. Burman, “Roth Conversions as Revenue Raisers: Smoke and Mirrors,” Tax Policy Center, May 11, 2006, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/url.cfm?ID=1000990.

[7] Jane G. Gravelle, “Budgetary Effects of Alternative Individual Retirement Account (IRA) Policies,” Congressional Research Service memorandum, February 27, 2006.

[8] Janet Hook, Carol E. Lee, and Cory Boles, “U.S. Budget Compromise Deal Reached,” January 1, 2013, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323820104578213242594177744.html.

[9] Suzy Khimm, “The worst budget gimmick in the fiscal cliff deal,” Wonkblog, January 2, 2013, http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/01/02/the-worst-budget-gimmick-in-the-fiscal-cliff-deal/.

[10] Joint Committee on Taxation score of the President’s FY2004 budget

[11] Jane G. Gravelle and Maxim Shevdov, “Proposed Retirement Savings Accounts: Economic and Budgetary Effects,” Congressional Research Service, Updated March 7, 2007. Estimates are in 2003 dollars.

[12]Leonard E. Burman, William G. Gale, Peter Orszag, “Key Thoughts on RSAs and LSAs,” Tax Policy Center, February 4, 2004, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/url.cfm?ID=1000600.

[13] Chye-Ching Huang, “Proposed Offset for Medical Device Tax Can’t Offset Anything — It’s a Timing Gimmick,” Off The Charts, October 3, 2013, http://www.offthechartsblog.org/proposed-offset-for-medical-device-tax-cant-offset-anything-its-a-timing-gimmick/.

[14] Chye-Ching Huang, Chuck Marr, and Nathaniel Frentz, “Timing Gimmicks Pose Threat to Fiscally Responsible Tax Reform,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 24, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3994.

[15] James B. Mackie III and John Kitchen, “Slowing Depreciation in Corporate Tax Reform,” Tax Notes Special Report, April 29, 2013.

[16] The “Pease” provision (after former Representative Don Pease) limits the value of itemized deductions for taxpayers with high incomes. “PEP” is a phase-out of the personal exemptions at high income levels.

[17] “News Conference With Representative Bill Thomas, Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee,” Federal News Service Transcript, March 15, 2001.

[18] Howard Kurtz, “The GOP's Fiscal Time Bomb,” The Daily Beast, December 2, 2010, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2010/12/02/tax-cut-extension-the-gops-fiscal-time-bomb.html.

[19] Chye-Ching Huang, “Budget Deal Makes Permanent 82 Percent of President Bush’s Tax Cuts,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 3, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3880.

More from the Authors