A key goal of tax reform should be to generate new revenue as part of a balanced deficit-reduction package that replaces sequestration and reduces long-term deficits.[2] Revenue savings can come from paring back costly and inefficient tax deductions, exclusions, and other tax breaks, known collectively as “tax expenditures.” And given that the nation faces long-term fiscal challenges, policymakers should design tax reform to ensure that the savings achieved during the first decade continue in the following decade.

That’s the standard Congress imposed in crafting health reform legislation in early 2010 and that the Senate recently used for immigration reform: the fiscal target for the first ten years must also be met for the second ten years.

Tax reform should be held to the same standard. Policymakers must resist using timing shifts that accelerate revenue from subsequent decades into the first ten years, as well as one-time revenue raising measures, to help meet their fiscal target for the initial decade — especially if such tax changes are coupled with rate reductions and other policies that have permanent costs. Such a combination would erode savings over time and could result in swelling long-run deficits.

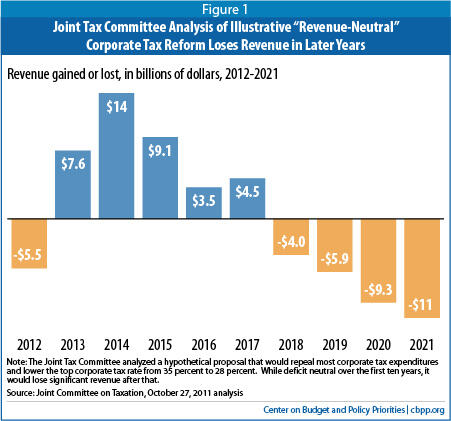

The temptation to use timing gimmicks is particularly serious in corporate tax reform, because many corporate tax subsidies are structured in such a way that scaling them back would generate much larger savings in the first ten years than over the long run.[3] As a result, a tax reform package that paired such cuts in corporate tax subsidies with permanent corporate rate cuts, which grow more costly over time, might shrink deficits initially but expand them significantly thereafter. For example, an analysis that the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) issued in 2011 found that a potential corporate tax-reform package that was revenue neutral over the ten-year budget window would produce annual revenue losses that would start before the end of the decade and grow over time.[4] (See Figure 1.) Timing gimmicks pose a danger in individual tax reform as well (see box).

The 1986 tax-reform law, which many tax-reform proponents cite as a model because it cut tax expenditures to pay for lower rates, offers a warning for current reform efforts. As Georgetown University tax law professor and former JCT chief of staff John Buckley notes: “The 1986 tax reform was financed to a very large extent by timing changes. . . . And the [law’s] rate reductions lasted a grand total of four years before they had to be reversed because the one-time tax increases from those timing changes were no longer there.”

[5]Policymakers should therefore insist on holding tax reform to a fiscal standard that extends beyond just the first decade.

Such a fiscal standard is not new. Congressional Democrats revised the health reform bill at the end of the legislative process in early 2010 to trim subsidies to purchase health coverage in the exchanges and to tighten the excise tax on high-cost health insurance plans, in order to ensure that the legislation would reduce the deficit in the second ten years as well as the first ten, under Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates. Likewise, the Senate “Gang of 8” designed the immigration bill that the Senate recently passed so that CBO would find that the bill would reduce deficits in the second decade as well as the first.

While most large corporate tax expenditures are structured in such a way that eliminating or scaling them back raises significantly less revenue after the first decade, this is not the case for most individual income tax expenditures. Nevertheless, some individual tax reforms could be used as timing gimmicks to hit tax reform’s revenue goals in the first decade but not after that.a A provision of January’s American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA) dealing with employer-sponsored retirement accounts is a clear example.

Amounts deposited in employer-sponsored retirement accounts like 401(k)s and 403(b)s are exempt from income tax when the deposits are made, but withdrawals in retirement are taxable. Some employers also offer “Roth” accounts, in which contributions are taxed up front but withdrawals in retirement are tax free. Prior to ATRA, taxpayers could shift money from accounts like a 401(k) into a Roth account only in very limited circumstances.

ATRA loosened the rules, allowing individuals to shift large sums (even their entire balances) from 401(k) and 403(b) accounts to a Roth account at any time. They would have to pay tax on the amounts shifted, but all subsequent earnings in the Roth accounts — and all withdrawals in later years — would be tax free. This maneuver raises revenue in the early years because people making the shift would pay income tax on the amounts that they moved to the Roth accounts — but loses revenue, and in larger amounts, outside the ten-year budget window. Only people who conclude they would pay less total tax over time will take advantage of this option, so the long-run effect will be a significant revenue loss.

This is not the first time that policymakers have adopted such a timing gimmick to disguise an individual income tax cut as a tax increase. Similar changes were made in 2006.b A future tax reform package could use changes in retirement savings rules and other provisions as timing gimmicks.

a See Chye-Ching Huang and Nathaniel Frentz, “Four Timing Gimmicks That Could Disguise Fiscally Irresponsible Individual Tax Reform,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 30, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=4041.

b Joel Friedman and Bob Greenstein, “Joint Tax Committee Estimate Shows That Tax Gimmick Being Designed To Evade Senate Budget Rules Would Increase Long-Term Deficits,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Revised April 26, 2006, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=220.

To illustrate the risk that timing gimmicks pose to fiscally responsible tax reform, this paper briefly discusses three prominent corporate tax reform options: ending accelerated depreciation, ending “last-in, first-out” accounting (LIFO), and adopting a territorial tax system. Proposals in these areas could raise significant revenue initially, but the savings would fade outside the ten-year budget window (and a territorial system could cause large and growing revenue losses).

By itself, the fact that the savings from a given set of tax changes may diminish over time doesn’t mean the changes aren’t worth doing. The key issue is what policymakers do with the savings — whether they offset tax changes that lose revenue and grow in cost over time, creating a mismatch that can lead to higher deficits over the long run. When considering a given package of reforms, policymakers must take account of both its short- and long-term budgetary impacts.

Eliminating nearly all major corporate tax expenditures would save $964 billion over 2012 to 2021, according to a 2011 JCT analysis. JCT stated that policymakers could use the savings to lower the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 28 percent without adding to deficits in the first decade. However, JCT also found that this package would add significantly to deficits in later decades.

As Figure 1 (based on the JCT analysis) shows, the new revenues generated by eliminating corporate tax expenditures more than offset the cost of lower corporate tax rates for the first few years.[6] But, starting in the seventh year, the package would cause a net revenue loss that would grow each year — and would continue over the long run.

The JCT analysis explains that many of the corporate tax breaks eliminated to fund the rate cut would raise more revenue in the first ten years than in any later decade. These tax expenditures allow corporations to delay paying tax; eliminating them boosts revenues initially, as corporations pay taxes earlier, but savings decline after that initial burst of tax revenues. John Buckley has explained, “Today, there is only one large corporate tax preference that is not a timing change and that’s the deduction for the manufacturing sector.”

The largest business tax subsidy, accelerated depreciation, allows businesses to deduct over time the cost of investments such as new equipment more quickly than those assets actually lose value. JCT’s analysis estimated that ending accelerated depreciation (so that businesses’ deductions would more closely reflect the rate at which assets deteriorate) would save $507 billion over the first ten years, or 53 percent of the total base-broadening savings in the JCT analysis. A number of prominent tax-reform plans — including the illustrative plan from Fiscal Commission co-chairs Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson, the plan from former Office of Management and Budget and CBO director Alice Rivlin and former Senator Pete Domenici of the Bipartisan Policy Center, and the plan from Senators Ron Wyden and Dan Coats — rely on ending or scaling back accelerated depreciation to generate revenues for corporate rate cuts or deficit reduction.[7]

The JCT estimates show, however, that revenue savings from ending accelerated depreciation would fall even within the first ten years, from a peak of $67 billion in the seventh year to $45 billion by the tenth year. A recent study by Treasury analysts James B. Mackie III and John Kitchen confirms that the savings would continue to shrink after the first decade.

[8] They found that ending accelerated depreciation saves much less revenue in the

second decade than in the first, and less in the third decade than in the second. After the fourth decade, they conclude that ending accelerated depreciation could pay for a corporate rate cut that’s only about 60 percent as large as the rate cut it could pay for over the first decade. This implies that if ending accelerated depreciation could fund (on a revenue-neutral basis) a corporate tax rate cut of about 3.7 percentage points in the first ten years, as JCT estimated, it could fund a cut of roughly only about 2.2 percentage-points over the long run.

[9] If policymakers ignored the long-run impacts, a corporate rate cut that policymakers could pay for in the first ten years by ending accelerated depreciation would raise deficits in the long run. Similarly, any deficit reduction achieved by ending accelerated depreciation would be significantly smaller in the long run than in the first ten years.

To calculate their taxable profits, businesses subtract from the income that they earn by selling goods what it cost them to produce or purchase these goods. “Last-in, first-out” accounting (LIFO) allows businesses generally to assign a higher cost to their goods for these purposes than other accounting methods do. This means that businesses using LIFO accounting can generally report lower taxable profits and therefore pay less in taxes.[10]

If policymakers repealed LIFO, these businesses would have to switch to the “first-in, first-out” (FIFO) accounting method. This would cause a large, one-time increase in their taxable income by forcing them to assign a new, lower cost to their existing inventories (that is, to the goods they have in stock but have not yet sold). To keep this one-time tax increase from causing some businesses cash-flow problems, proposals to repeal LIFO typically allow firms to spread the increase over a number of years.[11]

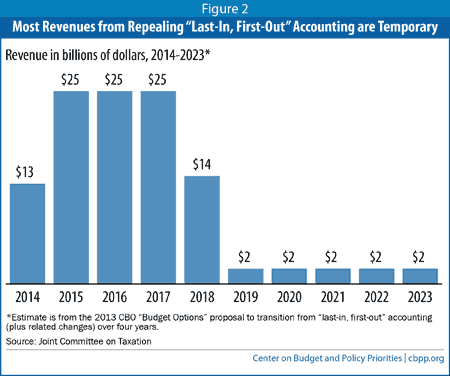

A Congressional Budget Office proposal to repeal LIFO would raise $112 billion over 2014 to 2023.[12] But, it also showed that the tax increase resulting from companies’ revaluation of their existing inventories is temporary. The change in valuing new stock in their inventories would produce only modest savings beyond the first five years, as Figure 2 shows.

The 2011 JCT analysis did not consider any changes to the international tax system, but policymakers could also use such changes as a timing gimmick.

The second-largest business tax expenditure, known as deferral, allows multinational corporations to delay paying U.S. taxes on their foreign profits until they choose to bring those profits back to the United States. This tax break cost $48.3 billion in 2013, according to JCT.[13] U.S.-based multinationals hold about $2 trillion[14] of foreign profits offshore, thereby deferring U.S. tax on these earnings.

Multinational corporations are calling for the United States to adopt a territorial tax system, which would give foreign profits even more favorable U.S. tax treatment by largely exempting them from U.S. taxation. The revenue loss from this change would grow over time because a territorial system would encourage multinationals to shift more profits and operations offshore.[15]

However, policymakers could temporarily mask this revenue loss: proposals to move to a territorial system often include a one-time tax on the $2 trillion of foreign profits that companies are now holding offshore (though companies may be allowed to pay that tax over a number of years).[16] This temporary revenue bump means that a territorial tax system might cost much less over the first ten years than over a longer period and might even raise revenue over the initial decade, despite losing significant revenues over the long term.

Even if policymakers were to enact an economically sound international tax reform that saved revenues over the long run — such as by adopting a minimum tax on foreign profits at an adequate tax rate, or ending or limiting deferral[17] — the transition to such a system could include a one-time tax on profits currently held offshore that could make tax reform look more fiscally sound than it actually is in the long run.

By using timing shifts or one-time tax savings, policymakers could assemble a tax reform package that meets the revenue targets for reform over the ten-year budget window but falls well short of those targets in subsequent decades. That would put greater pressure on future deficits. (It also would cause any revenue contribution to deficit reduction to dissipate in the long run, even as the contribution from entitlement cuts likely continued to grow.)

It is critical that policymakers hold tax reform to the same standard as major health and immigration reform proposals, so that the fiscal target that the proposal must achieve over the first ten years is also achieved during the subsequent decade.