Given the nation’s long-term fiscal pressures, increases in revenues need to make a significant contribution to deficit reduction, alongside reductions in spending for mandatory programs. Deficit-neutral tax reform would, as a result, be highly problematic.

Tax reform generally refers to a process through which policymakers would scale back the vast collection of tax deductions, credits, and other preferences, known collectively as “tax expenditures.” (For example, Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus and ranking Republican Orrin Hatch are undertaking a process in which Finance Committee members will examine and be asked to defend each tax expenditure that they want to retain in the code.[1] ) If tax reform were revenue neutral, it would use up the politically achievable savings from tax expenditures to lower rates without producing any deficit reduction, and it would effectively take revenue off the table for deficit reduction for years to come. It likely would take major mandatory programs off the table as well, because many policymakers would justifiably resist changes in those programs — which could significantly affect millions of people with relatively modest incomes — if they were not accompanied by revenue increases from reforming inefficient tax expenditures that disproportionately benefit the most affluent households.

Aggravating these risks, some prominent proponents of deficit-neutral tax reform have set, as a key tax-reform goal, a sharp cut in the top income tax rates. The House-passed budget resolution of this spring, for example, calls for setting a goal of cutting the top individual and corporate rates to 25 percent and offsetting that cost through unspecified tax-expenditure savings. The House rate-cut goals would dig a $5.7 trillion revenue hole over the next ten years, the Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center (TPC) has estimated, with the tax benefits heavily skewed to people at the top.[2] The task of finding anything close to that amount in tax expenditure savings would be politically herculean, given the popularity of such major and expensive tax expenditures as the mortgage interest deduction, the charitable deduction, and many others.

Consequently, policymakers would have strong incentive to use budget gimmicks and optimistic revenue forecasts (including the dubious tactic of “dynamic scoring”) to reach the stated goal of deficit-neutral tax reform. Thus, a purportedly revenue-neutral tax reform bill might be revenue neutral only cosmetically (or might be revenue neutral only over the first ten years and lose revenue after that due to the use of “timing-shift” gimmicks). If so, tax reform could wind up raising less revenue than current law over the long term, making long-term deficits worse.

Revenue-neutral tax reform also could lengthen the amount of time that policymakers leave the “sequestration” budget cuts in effect by making it harder to craft a balanced, long-term budget agreement to replace them. Sequestration, with its equal defense and nondefense cuts, was designed to bring bipartisan negotiators to the table in search of a broader agreement that would include both mandatory spending cuts and revenue increases. Revenue-neutral tax reform could doom that prospect as well.

Many recent tax reform proposals have several common elements: 1) calls to cut top tax rates on individuals and corporations, often to specific and historically low levels; 2) a goal of revenue neutrality; and 3) few if any specific proposals for how to achieve revenue neutrality — that is, how to offset the cost of the rate cuts. The 2012 plan of presidential candidate Mitt Romney is a well-known example. The latest budget plan of House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan, which the House adopted in its budget resolution this spring, is another.

Under such plans, policymakers could dig a big (and regressive) federal revenue hole by cutting tax rates deeply but not shrinking tax expenditures dramatically enough to fully offset the cost, prompting them to adopt various gimmicks to mask the tax cuts’ costs. Policymakers might even resort to “dynamic scoring” — the proposed process by which budget or tax technicians are supposed to assume that rate cuts generate large enough economic growth to drive up tax revenues, despite the lack of strong evidence for such results (and the difficulty of measuring any such effects).[3] Policymakers also might enact tax reform that’s revenue neutral in the first ten years but adds to deficits in the long run.[4]

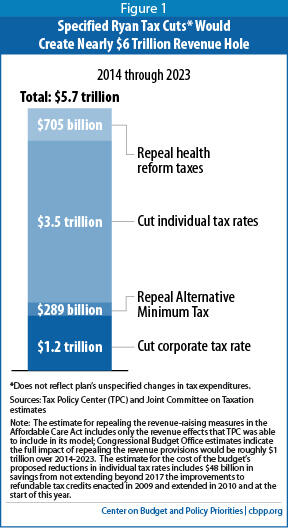

The fiscal year 2014 House budget resolution calls for cutting the top individual and corporate tax rates to as low as 25 percent, eliminating the individual Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), and repealing the revenue-raising measures in health reform. Those tax cuts would cost $5.7 trillion in lost federal revenue over the next decade, according to TPC estimates (see Figure 1). To put the $5.7 trillion figure in perspective, keep in mind that, at the outset of discussions in 2010 over a “grand bargain” to put the budget on a sustainable course, policymakers widely discussed a target of $4 trillion in deficit reduction over ten years.

[5] The cost of the House proposal is no surprise; tax rate cuts are very expensive. TPC analysis suggests that just a two percentage point rate cut would cost about $1.5 trillion over ten years,[6] a level that (as discussed in the next section of this paper) could easily exceed the level of tax-expenditure savings lawmakers can actually pass. For example, the Administration’s proposal to limit the value of various tax expenditures to 28 cents on the dollar, which has encountered stiff opposition from an array of constituencies and lawmakers, would raise about $500 billion — or about one-third of the cost of a two-percentage-point rate cut.[7]

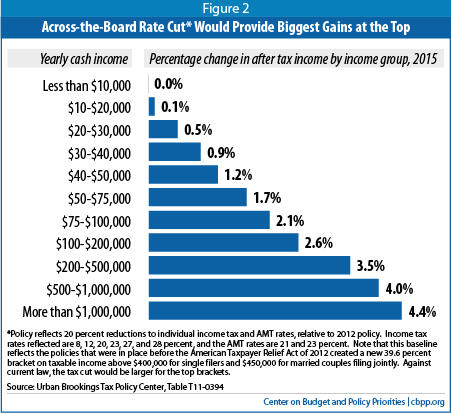

At first blush, across-the-board rate cuts may seem fair. Everybody gets the same percentage reduction in rates, so everybody should benefit equally. In fact, however, such rate cuts actually benefit the highest-income households much more.

To understand how, consider a simple tax system with two tax rates: 20 percent and 40 percent. Suppose both tax rates are cut by half, to 10 percent and 20 percent, respectively. Taxpayers would keep 90 cents — rather than 80 cents — of each dollar taxed at the bottom rate, generating a 12.5 percent increase in after-tax income. But for each dollar taxed at the top rate, high-income households would keep 80 cents, rather than 60 cents, generating a 33 percent increase in after-tax income. Although both tax rates fall by the same percentage, this would create a regressive tax cut that benefits people in the top bracket the most, not only in dollars but in the percentage increase in after-tax income (which many analysts regard as the best measure of whether a tax policy change is progressive or regressive).

Figure 2 illustrates the regressivity of a 20 percent across-the-board rate cut. Had policymakers cut rates by 20 percent from the levels in place before January’s American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA), they would have boosted after-tax incomes by 4.4 percent for people making over $1 million, compared to 1.7 percent for people making between $50,000 and $75,000. A 20 percent across-the-board rate cut would be similarly regressive today.

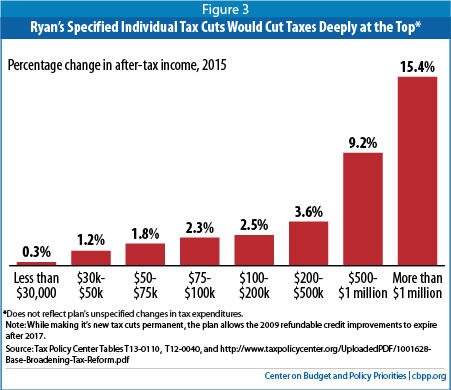

The fiscal year 2014 House budget resolution goes further; it calls for replacing the current seven tax brackets with two: 10 percent and 25 percent. That, too, would disproportionately benefit the most well-to-do. After-tax incomes would rise by an estimated 15.4 percent for people making over $1 million a year, compared to 1.4 percent for people making between $50,000 and $75,000, according to TPC analysis. (For more on potentially regressive tax changes, see Box 1.)

Policymakers could, of course, try to retain the tax code’s progressivity by cutting different tax rates by different percentages, although that wouldn’t solve the cost problem.

As this paper explains, across-the-board cuts in tax rates are regressive. If policymakers want to include such rate cuts in a tax reform plan while maintaining the progressivity of the tax code, they will have to design their reforms in tax expenditures and cuts to tax rates very carefully.

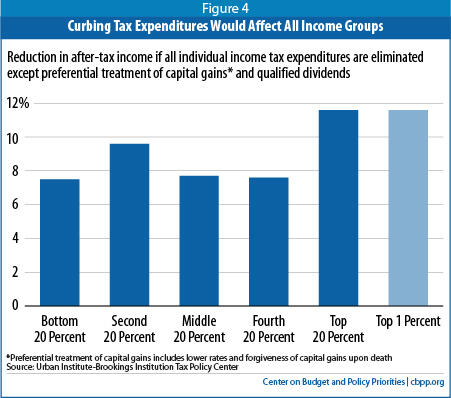

Maintaining progressivity would be especially hard if policymakers followed the lead of lawmakers like House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan and declined to scale back the tax expenditures from which high-income taxpayers benefit the most — the preferential tax rates for capital gains and dividends and step-up in basis at death. The benefits of the other major tax expenditures are actually somewhat progressive, as Figure 4 shows.a

Crafting and enacting a plan to cut the remaining tax expenditures enough to finance across-the-board rate cuts without hitting low- and moderate-income taxpayers harder than people at the top would likely prove unachievable.b

a Congressional Budget Office, “The Distribution of Major Tax Expenditures in the Individual Income Tax System,” May 29, 2013, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/43768, and Chuck Marr, “Chairman Ryan’s Misleading Chart,” Off the Charts Blog, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 27, 2012, http://www.offthechartsblog.org/chairman-ryans-misleading-chart/.

b Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, and Nathaniel Frentz, “The Ryan Budget’s Tax Cuts: Nearly $6 Trillion in Cost and No Plausible Way to Pay for It,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 17, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3926, and Samuel Brown, William G. Gale, and Adam Looney, “On the Distributional Effects of Base-Broadening Income Tax Reform,” Tax Policy Center, August 1, 2012, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/url.cfm?ID=1001628.

Tax expenditures cost the government more than $1 trillion per year in lost revenue, and reforming and scaling them back can make the tax code more efficient. The code’s vast array of deductions, credits, and other preferences reduces economic efficiency by favoring some forms of investment or economic activity over others. They often also give the largest subsidies to high-income families, even though such taxpayers generally least need a financial incentive to do whatever the tax break seeks to promote, such as saving for college or retirement. That makes such tax incentives inefficient and wasteful.[8]

But curtailing tax expenditures, especially by enough to offset the costs of rate cuts, is much harder politically than many proponents suggest. The more than $1 trillion per year in lost revenue has “created unrealistic expectations about the potential revenue that could be raised through tax expenditure reform,” notes Professor John Buckley, former chief of staff for the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT).[9] A Congressional Research Service (CRS) report issued last year similarly concluded:[10]

[T]here are impediments to base broadening by eliminating or reducing tax expenditures, because they are viewed as serving an important purpose, are important for distributional reasons, are technically difficult to change, or are broadly used by the public and quite popular. Given the barriers to eliminating or reducing most tax expenditures, it may prove difficult to gain more than $100 billion to $150 billion in additional tax revenues [in 2014] through base broadening.

Base broadening in this range, CRS notes, “would not allow for significant reductions in tax rates.” Such revenues would offset the cost of only “about a one or two percentage point reduction,” CRS explained. The author of CRS’ report, Jane Gravelle, reinforced this point and highlighted the challenges for tax reform in recent congressional testimony: [11]

First, it is difficult to identify base broadening provisions that realistically might be considered to allow significant rate reductions. Secondly, it is even more difficult to identify provisions that would allow significant reductions of the top rate, while maintaining the current distribution of tax burdens.

Indeed, President Obama’s proposal to cap the value of the largest individual tax expenditures (including such popular deductions such as those for mortgage interest and charitable giving and the exclusion for employer-provided health insurance) at 28 percent would raise $493 billion over ten years.[12] Policymakers would need to cut tax expenditures by over ten times as much as the Obama proposal to pay for the House rate-cut proposals. Yet, the Obama proposal continues to face strong opposition on Capitol Hill.[13]

Compounding the revenue problem is an often overlooked fact: the more that income tax rates fall, the less revenue that policymakers can raise by scaling back tax expenditures. Most tax expenditures reduce the amount of a taxpayer’s income that’s subject to income tax rates, so their cost depends on the taxpayer’s marginal tax rate. For example, each additional $1 deduction reduces revenues by 15 cents if a taxpayer is in the 15 percent tax bracket but by almost 40 cents if the taxpayer is in the 39.6 percent bracket. When tax rates fall, the cost of these tax expenditures falls with them — and, as a result, policies to scale them back raise less revenue. TPC analysis suggests that cutting rates by 20 percent and eliminating the AMT would reduce revenues available from base broadening by roughly 20 percent.[14]

Let’s suppose policymakers craft a tax reform bill that’s truly deficit neutral — such as by scaling back their desired rate cuts and making sufficient changes in tax expenditures to offset the cost. That would create a serious problem of its own by paralyzing efforts to reach a long-term deficit reduction agreement, possibly for a number of years.

If policymakers enact deficit-neutral tax reform, they will have made the politically possible changes in tax expenditures while locking in lower tax rates. Because policymakers would have nowhere else to go on the tax expenditure front, revenue would likely be effectively off the table for the further deficit reduction that — despite the fiscal improvement in recent years — is still needed to put the nation on a sustainable long-term path.[15]

The fiscal ramifications would extend beyond revenue. Politically speaking, any large long-term budget agreement will likely include both reductions in mandatory spending (for example, in Medicare) and additional revenue. Those who oppose mandatory spending cuts would almost certainly relent only if the proponents of such cuts agree to team them with tax increases. So, deficit-neutral tax reform would likely take such spending cuts off the table as well, leaving policymakers nowhere to turn for more mid-term and long-term deficit reduction.

Proponents of broadening the tax base and lowering tax rates often tout the potential for such measures to boost economic growth. Policymakers can and should seek to reform tax expenditures in ways that make the tax code more efficient. The economic gains, however, would likely prove modest.

Some studies have found significant efficiency gains from fundamental tax reform, but “[m]ost economists asserting the economic benefits of tax reform are modeling their vision of an ideal tax system,” notes John Buckley, former Joint Tax Committee chief of staff and former chief tax counsel for the House Ways and Means Committee. “Most often, it is a vision that would have little political viability and unrealistically low rates because of the omission of items like transition relief.”a

Brookings Institution tax economist William Gale writes that “there are particular reasons to be skeptical that revenue-neutral tax cuts will have much effect on growth. While lower tax rates provide a stronger incentive for employment and saving, base-broadening measures would increase the portion of Americans’ income that is subject to tax, and this would create incentives that would work in the other direction. At the end of the day, the net effects on labor supply and saving behavior would likely be small.”b

As a case in point, the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA86) — the last major effort to broaden the tax base and reduce rates — appears to have produced little impact on economic growth. Summarizing the results of a conference sponsored by the University of Michigan, Henry Aaron, another Brookings tax expert, wrote, “Most of the papers presented at this conference reinforce the casual observation that TRA86 has had little effect on the broad measures of real economic activity in which most economists are interested.”c

Moreover, the economy will likely grow faster over the long term if policymakers use the revenues they raise from tax reform primarily for deficit reduction rather than tax rate cuts. That’s why the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) concluded in 2012 that letting President Bush’s tax cuts expire and dedicating the revenues to deficit reduction would ultimately raise U.S. residents’ income more than otherwise, and that the boost to national saving would outweigh any loss of economic efficiency due to the higher taxes.d A tax reform package that achieved modest efficiency gains from base broadening but contributed little if anything to deficit reduction would likely do less for long-term economic growth than limiting tax expenditures and applying the savings in whole or substantial part to deficit reduction.

a John L. Buckley, “Written Testimony Of John L. Buckley, Visiting Professor Georgetown University Law Center Committee On Ways And Means,” September 21, 2011, http://waysandmeans.house.gov/uploadedfiles/buckley_testimony921.pdf. For example, previous JCT studies of base-broadening, rate-lowering tax reform have omitted transition relief; see Thomas A Barthold, Letter to Senate Committee on Finance Chairman Max Baucus and Ranking Member Orrin G. Hatch, October 12, 2012, http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/files/2012/10/BN_101212_192832.pdf. Similarly, an illustrative tax reform example from CBO does not explicitly account for transition relief; see Congressional Budget Office, “Choices for Deficit Reduction,” November 8, 2012, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/43692, p. 25.

b Samuel Brown, William G. Gale, and Adam Looney, “On the Distributional Effects of Base-Broadening Income Tax Reform,” Tax Policy Center, August 1, 2012, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/url.cfm?ID=1001628.

c Henry J. Aaron, “Lessons for Tax Reform,” in Joel Slemrod (ed.), Do Taxes Matter? (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990), p. 322.

d Douglas W. Elmendorf, Director, Congressional Budget Office, “The Economic Outlook and Fiscal Policy Choices,” Testimony before the Senate Committee on the Budget, September 28, 2010, http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/118xx/doc11874/09-28-EconomicOutlook_Testimony.pdf.

The President and Congress created sequestration in the 2011 Budget Committee Act. If the congressional “supercommittee” failed to craft a plan to reduce deficits by $1.5 trillion over the next decade (as it did), then sequestration would generate $1.2 trillion in budget savings through nine years of automatic annual budget cuts, with an equal mix from defense and non-defense programs.

Policymakers assumed that, facing such a blunt process and such mindless cuts to both defense and non-defense programs, the President and Congress would come together on a long-term plan that would replace sequestration with a better designed, more balanced approach to deficit reduction.

Defying those expectations, sequestration took effect this spring and will almost certainly remain in effect for the rest of the current fiscal year. Moving forward, the political path to ending it remains the same — replacing it with a broad, balanced plan of both more revenues and savings in mandatory programs that help address the long-term budget challenge.

Deficit-neutral tax reform that claims the politically achievable savings from scaling back tax expenditures and locks in lower tax rates makes that more balanced deal much harder for policymakers to craft. The harder it is from them to craft it, the longer that sequestration will likely remain in effect.

The primary goal of tax policy should be to raise additional revenue, in a progressive fashion, as part of a balanced approach to long-term fiscal health. The primary goal should not be to cut tax rates further.

Tax expenditures should be a prime target for revenue raising. For one thing, they suffer from a key design flaw — their value rises as household income rises, so they provide the biggest benefits to the people who least need a tax incentive to buy a home, save for retirement, send a child to college, or the like. For another, they make the tax code less efficient by favoring some activities over others. Thus, policymakers can secure tax-expenditure savings while, at the same time, boosting the efficiency of the tax code. Yet most large tax expenditures are popular and deeply embedded in the tax code. Policymakers must be realistic about the amount of savings they can generate — and they should not apply them solely to cutting tax rates and, thus, creating new obstacles to deficit reduction.[16]

Policymakers should follow a first-things-first sequencing. They should pursue tax-expenditure reform as part of a balanced long-term deficit plan that also includes spending reductions. And policymakers should apply a share of the proceeds to lower rates only if they have first met the revenue targets of such a balanced deficit plan.