The revenue raised as part of January’s American Tax Relief Act (ATRA) came primarily as a result of raising tax rates on high-income households. Yet throughout the negotiations around avoiding the fiscal cliff last year, both President Obama and Speaker Boehner called for raising revenue through limiting tax deductions, exclusions, and other tax breaks known collectively as “tax expenditures.” Indeed, Speaker Boehner suggested that all of the $800 billion of additional revenue in his initial December 3 offer could be raised by limiting tax expenditures rather than by raising tax rates. The additional revenue from reforming tax expenditures remains untapped and is available to make a significant contribution to deficit reduction as part of a balanced deficit reduction package of spending reductions and revenue increases (see Box 1 on why revenue should be part of deficit reduction).

Tax expenditures are ripe for reform: they are costly, reducing revenues by over $1 trillion annually, and they are often poorly designed for achieving their desired policy goals. In many cases, there is little difference between benefits or subsidies provided through the tax code and benefits or subsidies provided through the spending side of the budget. So efforts to reduce spending should also address spending in the tax code. Further, tax expenditures tend to provide a disproportionate share of benefits to households higher up the income scale. Thus, tax expenditure reforms are likely to be substantially more progressive than changes to entitlement programs, which tend to provide the bulk of their benefits to lower- and middle-income households.

During last year’s budget negotiations and even during the presidential campaign, there was some bipartisan interest in addressing tax expenditures through a type of across-the-board limitation. This approach has the attraction of treating a number of tax expenditures in a similar fashion and obviates the need for Congress to develop extensive reforms specific to individual provisions. A well-designed limitation could retain tax subsidies to encourage activities regarded as producing social or economic benefits, but limit those subsidies to make them more cost-effective and less regressive. Of the various limitation proposals that have emerged to date, the President’s proposal to limit the value of itemized deductions and certain other tax expenditures to 28 cents on the dollar has the soundest design. It would retain tax incentives for desired activities (such as charitable giving) rather than eliminating such incentives altogether for some taxpayers, reduce tax-code inefficiencies (under which high-income taxpayers get larger tax-incentive subsidies to undertake certain activities than lower- and middle-income households do, even when the high-income taxpayers generally would engage in the activities anyway and lower- and middle-income households are the ones more responsive to the tax incentives), and be progressive.

As policymakers enter the next stage of the budget negotiations, a key question is the extent to which new revenues should contribute to additional deficit reduction. Republican Congressional leaders have said that new revenue is off the table. President Obama has called for new deficit reduction to contain a balance of spending cuts and revenue increases.

To date, spending cuts have accounted for the bulk of the total policy savings. Specifically, Congress has enacted several pieces of legislation — most notably the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA) — that will cut discretionary funding by nearly $1.5 trillion over the 2013-2022 period.a On the revenue side, the recent American Tax Relief Act (ATRA) will generate an estimated $561 billion in additional revenue over 2013-2022.b When the related savings in interest payments are included, a total of $2.35 trillion of deficit reduction has been achieved over the 2013-2022 period. Over the new budget window of 2014-2023, these same policies produce estimated savings of $2.75 trillion.

We estimate that $1.5 trillion in additional deficit reduction over 2014-2023, reflecting policy savings of about $1.3 trillion and interest savings of $200 billion, would stabilize the debt at about 73 percent of GDP over the coming decade.c Stabilizing the debt is an important goal to ensure that the debt doesn’t grow faster than the economy and risk eventual economic problems.

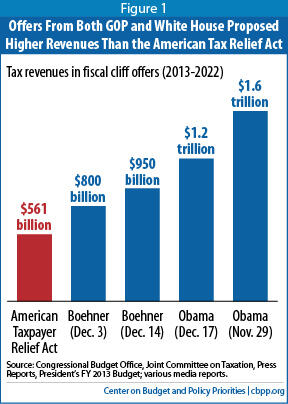

It would be difficult to achieve well over $1 trillion in additional policy savings through spending cuts alone without worsening poverty and inequality, increasing the ranks of the uninsured, or jeopardizing investments important to future economic growth such as education, infrastructure, and basic research. During the “fiscal cliff” negotiations, every public offer from both the President and congressional Republicans included revenue increases of a substantially larger amount than ATRA’s $561 billion (see Figure 1).

a Richard Kogan, Robert Greenstein, and Joel Friedman, “$1.5 Trillion in Deficit Savings Would Stabilize the Debt Over the Coming Decade,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 11, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3900.

b These savings are relative to the revenues that would have been collected if policymakers had extended all expiring income and estate tax cuts, net of other tax changes in ATRA. This total reflects $624 billion over the 2013-2022 period from raising taxes on upper-income households by allowing certain provisions enacted in 2001 and 2003 to expire at the end of 2012, as well as the effects of other revenue provisions in ATRA, including the temporary continuation of the so-called “tax extenders.” The continuation of the tax extenders through 2013 reduced tax revenues by $76 billion, which is the main reason that the net tax savings from ATRA are $561 billion, rather than more than $600 billion.

c Kogan, Greenstein, and Friedman, February 11, 2013.

Policymakers also should close various tax breaks that allow wealthy people to pay much lower or no taxes on certain forms of income. In many cases, these tax breaks cannot be addressed through an across-the-board tax expenditure limit, or it may make more sense to restructure (or repeal) these tax breaks directly. Examples of such tax breaks include:

- Carried interest. This tax break allows investment fund managers to pay taxes on a large part of their income — their “carried interest,” or the right to a share of the fund’s profits — at the 20 percent capital gains tax rate rather than at normal income tax rates of up to 39.6 percent, even though they did not invest their own capital and the “carried” interest represents compensation for work they have performed. As a result of this tax break, a hedge fund manager earning $10 million or more can pay a smaller share of his income in federal income taxes than a middle-income schoolteacher or police officer.

- “Like-kind” exchanges. The sale or exchange of property for money or other property generally triggers capital gains tax, but no tax is levied on the exchange of property for what the tax code loosely defines as “like-kind” property. Congress apparently intended this tax treatment as a way to exempt small-scale and informal barter transactions from taxation and the attendant reporting requirements. But this tax break is now used on a much broader scale and has become subject to abuse. As a recent New York Times article on the explosive growth of the tax break noted, “Over the years . . . the practice of exchanging one asset for another without incurring taxes spread to everyone from commercial real estate developers and art collectors to major corporations.” [1]

- Valuation discounts. Estate tax law allows wealthy households to substantially discount the value of assets that they transfer to heirs — in other words, to claim that the assets are worth much less than their face value — if certain restrictions apply to the use of those assets (for example, if the assets are placed in a business entity known as a family limited partnership and can be sold only to other family members). Such valuation discounts, by shrinking the value of the estate, lower the amount of estate tax owed on it. In what tax expert Calvin Johnson calls “now-you-see-them, now-you-don’t arrangements,” some high-income households exploit this loophole by imposing temporary restrictions on assets they are transferring and then use those restrictions to claim a significant valuation discount on the assets. When the restrictions expire, the heirs end up with the full value of the assets while avoiding estate tax that otherwise would be due.

- S corporation loophole. An S corporation is a “pass-through” company, which means that the profits of the business are exempt from corporate income tax, and instead “passed through” and taxed only as income of the shareholders. Many S corporation shareholders receive both wages from the S corporation and a share of the S corporation’s profits, but they pay payroll tax only on their wages. This gives them an incentive to underreport the share of their income that consists of wages in order to reduce their payroll tax liability. GAO and the Treasury Inspector General have studied this tax avoidance issue, which was made famous by John Edwards and Newt Gingrich, who both exploited this tax break.[2] Several proposals have been advanced to address it.

- Inside buildup of life insurance. Some types of insurance policies essentially operate as investment products, accumulating value during the policyholder’s lifetime as the insurance company invests a portion of the premiums. The investment earnings — the so-called “inside buildup” — are not taxed as they accrue or are realized within the fund, and they are never taxed if they are retained and then paid out upon the policyholder’s death, or if they are used to pay premiums for the life insurance policy (taking the place of payments that the policyholder would otherwise make with after-tax dollars). Other savings and investment vehicles, such as bank accounts and mutual funds, do not have tax preferences of this generosity and scope.

There is strong support on both sides of the aisle for reforming tax expenditures. The tax reforms proposed by both the Bowles-Simpson Fiscal Commission and the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Debt Reduction Task Force (chaired by former Office of Management and Budget and Congressional Budget Office director Alice Rivlin and former Senator Pete Domenici) included extensive changes to tax expenditures. Tax expenditures are ripe for reform because:

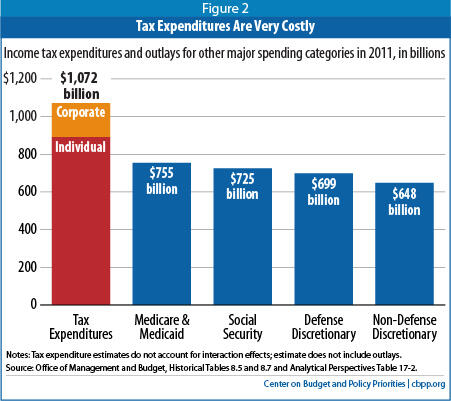

- They are costly. Tax expenditures cost nearly $1.1 trillion a year in 2011. If classified as spending, they would constitute the single largest category of federal spending — larger than Social Security, or the combined cost of Medicare and Medicaid, or defense or non-defense discretionary spending (see Figure 2).[3]

-

Many tax expenditures have a flawed “upside down” design. Roughly 70 percent of each year’s spending on individual tax expenditures results from deductions, exemptions, or exclusions. The value of these tax breaks increases as household income rises — the higher one’s tax bracket, the greater the tax benefit for each dollar that is deducted, exempted, or excluded.

As a result, these tax expenditures provide their largest subsidies to high-income people even though those are the individuals least likely to need a financial incentive to engage in the activities that tax incentives are generally designed to promote, such as buying a home, sending a child to college, or saving for retirement. Meanwhile, middle-class families receive considerably smaller tax-expenditure benefits for engaging in these activities. In this regard, these tax expenditures are “upside down,” which makes them less efficient, as well as less equitable.

Consider how the deduction for home mortgage interest affects two households’ decisions to buy a home. An investment banker making $675,000 who has a $1 million mortgage and pays $40,000 in mortgage interest each year receives a housing subsidy of about $14,000 annually from the mortgage interest deduction.[4] By contrast, a middle-class family led by a nurse making $60,000, and paying $10,000 a year in mortgage interest on a more modest home, receives a housing subsidy worth $1,500 annually. Not only does the mortgage interest deduction provide the high-income banker with a larger total subsidy (in dollar terms) than the nurse, but the subsidy also represents a greater share of the banker’s mortgage interest expenses. In fact, the proportion of the banker’s mortgage interest expense covered by the subsidy is more than twice as large as the percentage subsidy that the nurse receives.

-

Many tax expenditures do not differ fundamentally from spending. The distinction between tax breaks and spending is often artificial and without economic basis. Education is one example. On the spending side of the budget, the federal government provides Pell Grants to help low- and moderate-income students afford college. On the tax side of the budget, so-called 529 accounts help parents pay for college by providing tax subsidies that are most generous for upper-income households. Both of these policies are government subsidies to promote higher education; the tax/spending distinction is not meaningful here.

Child care provides another example of why tax expenditures generally are the equivalent of spending programs and essentially operate as entitlements. Many low- or moderate-income people receive a subsidy, provided through a spending program, to help cover their child care costs. Many people with higher incomes similarly receive a subsidy that reduces their child care costs, but they receive it in the form of a tax credit. The child-care spending programs that serve lower-income families are not open-ended entitlement programs; they serve only as many people as their capped funding allows, and only about one in six eligible low-income working families receives this assistance.[5] By contrast, the child care subsidies for higher-income families operate as an open-ended entitlement provided through the tax code, and all families eligible for the tax credit can get it. The current structure, in which child care subsidies are constrained for lower-income families but unlimited for higher-income families, makes little sense. (It would also make little sense to target the child care subsidy for low-income parents for deficit reduction while leaving the child care subsidy for higher-income parents untouched because the former is delivered through a “spending” program and the latter is delivered through the tax code.)

For reasons such as these, Harvard economist Martin Feldstein, former chair of President Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers, has urged policymakers to scale back tax expenditures, and has written that “cutting tax expenditures is really the best way to reduce government spending.”[6] Former Federal Reserve Board Chair Alan Greenspan has referred to tax expenditures as “tax entitlements” and said they should be looked at alongside spending entitlements.

There is also an equity issue here. “Spending” entitlements provide most of their benefits to middle- and lower-income households, while tax-expenditure benefits — or “tax entitlements” — go heavily to high-income households. If policymakers exempt tax expenditures from deficit reduction, that is likely to place the onus of further deficit reduction entirely on spending programs and to result in regressive outcomes that further widen inequality and increase poverty.[7]

Using savings from tax expenditure reform just to cut tax rates, without shrinking deficits, would be similarly ill-advised.[8] The current political environment remains inhospitable to a new tax such as a carbon or a value-added tax, essentially leaving policymakers with two opportunities to secure substantial revenue to help address deficits in a balanced way: raising tax rates and curbing tax expenditures. The fiscal cliff deal secured about $600 billion by allowing tax reductions for high-income households to expire; further tax-rate increases now are unlikely. This leaves only tax expenditures. If achievable savings from reducing tax expenditures are dedicated largely or entirely to cutting tax rates instead of to reducing the deficit, then that will use up the last remaining politically plausible source for a meaningful revenue contribution to deficit reduction. Revenue-raising to reduce the deficit could then be off the table for many years.

Many assume that tax reform that uses savings from broadening the base to lower tax rates will yield substantial economic benefits, which will in turn generate new revenues. The literature in the field indicates, however, that the economic benefits of revenue-neutral tax reform are likely to be much more modest. Economic studies lead to the conclusion that reducing the deficit and restoring long-term fiscal stability would be likely to yield significantly greater benefits for economic growth over the long term than would broadening the tax base and using the proceeds to lower tax rates.[9] The first call on savings from narrowing tax expenditures should be to apply them to deficit reduction, alongside further spending reductions.

Leaders of both parties have proposed across-the-board limits to tax expenditures. President Obama’s budgets include a detailed proposal for one such limit; during the presidential campaign, Governor Romney floated a different type of limit (both proposals are discussed below). In addition, policymakers from both parties discussed tax-expenditure limits during the “fiscal cliff” negotiations.

House Speaker John Boehner initially suggested raising $800 billion in revenues, entirely from reductions in tax expenditures, as an alternative to raising tax rates for high-income people. While he did not make a specific proposal, congressional Republican staff pointed to a Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) paper that outlined three basic options:[10]

1. Limiting itemized deductions to $25,000 for high earners. Governor Romney suggested such a “dollar cap approach” during the presidential campaign. In November 2012, Senator Bob Corker (R-TN) proposed capping itemized deductions at $50,000 for all taxpayers.[11] The specific option outlined by CRFB would limit itemized deductions to $25,000 for taxpayers making above $250,000 for married couples filing jointly ($200,000 for singles); as incomes rose above $500,000 for couples ($400,000 for singles), the maximum deduction allowed would phase down and ultimately disappear.

The fiscal cliff deal reinstated a limit on itemized deductions for high-income taxpayers known as the “Pease” provision, which policymakers created as part of the 1990 bipartisan deficit-reduction package but the Bush tax cuts phased out between 2001 and 2010. Pease reduces the total amount of a taxpayer’s allowable itemized deductions by 3 percent of the amount by which the taxpayer’s adjusted gross income (AGI) exceeds certain thresholds — $300,000 for married couples filing jointly and $250,000 for single filers.

Pease does not, however, obviate the need for tax-expenditure reform. It leaves in place a vast array of costly and inefficient tax expenditures that policymakers should reform both to help reduce budget deficits and to clean up and improve the efficiency of the tax code.

In particular, Pease does not correct the “upside-down” design of deductions and exemptions, which give their largest subsidies to high-income people, even though those often are the people who least need a financial incentive to take the action that the tax incentive is designed to promote, such as buying a home, sending a child to college, or saving for retirement. In addition, Pease doesn’t touch the numerous tax expenditures that come in the form of exclusions, exemptions, or preferential rates.

Policymakers can complement Pease with well-designed tax-expenditure reforms or limitations. The tax code remains full of tax breaks that are ripe for reforms that could generate revenues for deficit reduction while improving the efficiency and equity of the tax code.*

* See Chye-Ching Huang and Chuck Marr, “Raising Today’s Low Capital Gains Tax Rates Could Promote Economic Efficiency and Fairness, While Helping Reduce Deficits,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 19, 2012, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3837.

2. Capping the after-tax value of certain tax expenditures for high earners. This option, designed by Martin Feldstein, National Bureau of Economic Research researcher Daniel Feenberg, and CRFB head Maya MacGuineas, would cap at 2 percent of a household’s adjusted gross income the combined value of a number of tax expenditures, including itemized deductions and certain tax exclusions (including the exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance) and the Child Tax Credit.

3. Limiting the value of certain tax expenditures to 28 percent. President Obama proposed in his 2013 budget to limit — to 28 cents on the dollar — the value of itemized deductions, most above-the-line deductions, and the exclusions for employer-sponsored insurance, interest on municipal bonds, and foreign-earned income. The proposal would affect only high-income taxpayers in tax brackets higher than 28 percent, as well as those who would be in these tax brackets if not for deductions and exclusions subject to the limitation. Citizens for Tax Justice estimates that just 3.6 percent of taxpayers would face a tax increase under the proposal.[12]

The 28 percent limitation reduces, but does not eliminate, the “upside down” nature of the major individual tax expenditures. High-income taxpayers, for example, would receive a tax subsidy on mortgage interest worth 28 cents on the dollar, compared to 10, 15, or 25 cents on the dollar for a middle-income filer. The gap, however, would be smaller than under current law. (Policymakers could go further along the lines of the Bowles-Simpson and Rivlin-Domenici panels and the Bush Administration’s tax reform commission, all of which proposed, for example, subsidizing mortgage interest at the same rate for all taxpayers by converting the mortgage interest deduction into a tax credit at a flat percentage of mortgage interest costs — such as 12 percent or 15 percent — for all tax filers.)

Relative to these other two approaches to fashioning a tax-expenditure limitation, the most important design feature of the President’s proposal is that it retains incentives at the margin for deductible expenditures. That is, wealthy taxpayers would still receive a deduction worth 28 cents on the dollar for all deductible expenditures. In contrast, the other two options would eliminate all incentives once a taxpayer reached the dollar limit of the cap (under the first option) or hit the 2 percent of AGI cap (under the second option); taxpayers would receive no deduction for otherwise deductible expenses once the dollar limit or AGI cap was reached.

This difference in design between the President’s proposed limitation and the other two types of limitations is particularly important for charitable giving. Under the President’s proposal, a wealthy taxpayer would retain a substantial incentive to give to charity, as $1 in charitable donations would effectively cost the taxpayer 72 cents. Recent estimates by the nonpartisan Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (TPC) indicate that total charitable contributions would decline only modestly — by an amount equal to between 1.6 and 3.0 percent of total charitable giving.[13] By contrast, under the other two approaches, many wealthy taxpayers would effectively receive no tax incentive to donate, with a $1 in a charitable giving costing them a full $1.[14]

The ability to deduct charitable donations lowers the “price” of giving, making it more attractive. When taxpayers in the 39.6 percent top income bracket deduct a $100 gift to charity from their adjusted gross income, that deduction reduces their taxable income by $100 and their tax bill by $39.60. In effect, the $100 donation costs them only a little over $60. Economists agree that the most important question about how a tax provision such as an across-the-board tax expenditure limit affects total charitable giving is how it changes the subsidy for an additional dollar of donations.

A hard cap on itemized deductions — at a specific dollar amount or a specific percentage of AGI — would eliminate the tax incentive for many high-income filers to make additional donations. Once filers had enough deductions to reach the cap, they would receive no deduction — and therefore no tax subsidy — for further charitable giving. Their marginal tax incentive to give more would be cut from 39.6 cents in the dollar to zero.

Moreover, a hard-cap approach would eliminateincentives for all charitable giving — not just additional donations — among the many high-income taxpayers who would hit the cap before making any charitable donations. If these taxpayers’ deductions for other items such as mortgage interest and state and local taxes consumed the full amount allowed under the cap — as would often occur — they would receive no tax benefit from making charitable donations. In general, taxpayers who lived in states with relatively high taxes (or who had relatively large mortgages) would have a smaller incentive for charitable giving, because they would be more likely to hit the hard cap before any charitable contributions were taken into account.

By contrast, a 28 percent limit on itemized deductions and various other tax expenditures would leave in place a tax subsidy for unlimited amounts of charitable giving by high-income filers. Regardless of how much a household claimed in charitable donations or other deductions, it would receive a tax subsidy of 28 cents on the dollar for additional amounts of charitable giving. For this reason, the Tax Policy Center estimates suggest that such a limit would have a modest impact on total charitable giving, reducing it by between 1.6 to 3 percent.a

a See footnote 13 in text.

While an across-the-board limitation can address many tax expenditures, some are embedded in the tax code in a way that would make it difficult or impossible to touch them through such a limitation. These types of tax breaks should be addressed directly, with carefully designed policies.

In particular, policymakers should examine tax breaks that enable various people with high incomes to avoid substantial amounts of tax on that income (and do so without creating incentives for desirable activities such as homeownership or charitable giving). Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers wrote recently that policymakers “should be able to come together around the idea that it should not be possible to accumulate and transfer large fortunes while avoiding taxation almost entirely. Yet this is all too possible today.”[15] For many of these tax breaks, it would make sense to restructure or eliminate them independently, rather than to try to include them in an overall tax expenditure limit. Doing so could help to finance a replacement for the scheduled 2013 sequestration, or contribute to a larger effort to stabilize the debt as a share of the economy. Some examples of these tax breaks are described below.

Managers of private equity funds typically receive, as compensation for their work, a management fee plus 20 percent of the fund’s profits above a threshold level. This right to 20 percent of the profits is known as “carried interest.” Currently, the managers’ carried interest is taxed as capital gains, meaning that it faces a top tax rate of only 20 percent regardless of how affluent a fund manager is and what tax bracket he or she falls in.

The carried interest that fund managers receive is compensation for the work they perform in managing a fund’s investments, not a return on capital of their own that they have invested.[16] Fund managers tend to contribute a modest amount of capital to the funds they manage, but any gains they receive on those investments are taxed at the capital gains rate and would continue to be taxed that way under proposals to eliminate the tax preference for carried interest.

The current preferential tax treatment means that a hedge-fund manager earning $10 million a year can pay a smaller share of his income in federal income taxes than a middle-income schoolteacher or a police officer. Most tax policy analysts believe that the tax code should treat compensation that is paid as carried interest the same as it treats the income that other Americans receive for the work that they perform.

As one tax attorney has written, “The Section 1031 ‘like-kind’ exchange is a powerful tax-deferral technique that has, for the most part, escaped rigorous Congressional scrutiny.”[17] A recent front-page New York Times story[18] detailed the explosive growth of this tax break:

It began more than 90 years ago as a small tax break intended to help family farmers who wanted to swap horses and land. Farmers who sold property, livestock or equipment were allowed to avoid paying capital gains taxes, as long as they used the proceeds to replace or upgrade their assets.

Over the years, however, as the rules were loosened, the practice of exchanging one asset for another without incurring taxes spread to everyone from commercial real estate developers and art collectors to major corporations. It provides subsidies for rental truck fleets and investment property, vacation homes, oil wells and thoroughbred racehorses, and diverts billions of dollars in potential tax revenue from the Treasury each year.

This is how it works. The sale or exchange of appreciated property for money or other property generally triggers capital gains tax. But Section 1031 of the Internal Revenue Code provides that the disposition of property held for use in a trade or business or for investment purposes does not trigger the capital gains tax if it is exchanged for “like-kind” business or investment property. Any gain realized on a like-kind exchange is deferred from taxation until the owner sells the replacement property, and the tax can be deferred once again at that point by using the replacement property in yet another “like-kind” exchange. Moreover, if the owner passes the property to an heir instead of selling it, capital gains tax is not just deferred but permanently eliminated, since capital gains become exempt from taxation once the individual who owns the asset dies.

The problem here is that, as the Congressional Research Service has noted, Section 1031’s definition of “like kind” is “loose.” For example, it regards all real property (land and improvements) as “like kind,” despite large differences in the quality, location, condition, and development of different types of real estate. For example, a property developer could swap out an undeveloped piece of land in a risky new development on the outskirts of a town for a downtown office building occupied by a long-term Blue-Chip tenant. Swapping such different investments is no different than swapping shares of one stock for shares of another, which does appropriately trigger capital gains tax on the profit made on the stock that was sold.

While Congress apparently intended Section 1031 as a way to exempt small-scale and informal barter transactions from taxation and the attendant reporting requirements,[19] like-kind exchanges typically are no longer small-scale, informal barter. Instead, a taxpayer who wishes to dispose of an asset on which there is unrealized capital gain and to avoid tax on that gain will typically approach a broker. The broker will identify a potential purchaser for the asset. The purchaser will transfer cash to the broker, who will use the funds to identify and purchase a property on the purchaser’s behalf that the taxpayer regards as a suitable replacement. The purchaser and the taxpayer then exchange the assets, with the broker “keep[ing] the available cash out of the hands of the taxpayer so that he will not receive and be taxed on the cash.”[20] There is a nationwide cottage industry of commercial intermediaries who specialize in brokering these complex transactions.[21]

The like-kind exchange provision is a strong candidate for reforms to rein in its excesses or repeal it.[22]

The estate tax has been weakened considerably in recent years. Under ATRA, wealthy couples can pass on $10.5 million to their heirs tax free in 2013. This generous exemption level, combined with tax breaks for various types of estates, means that the estates of 99.86 percent of people who die will be exempt from the tax entirely in 2013, according to the Urban Institute-Brookings Tax Policy Center.[23] The Tax Policy Center also estimates that the tax imposed on the few large estates that will owe any tax will be relatively modest on average. For the 0.14 percent of estates that TPC estimates will owe tax in 2013, the average effective tax rate will be only 16.6 percent. (In other words, the tax will, on average, equal 16.6 percent of the value of these very large estates.)

Given these generous parameters, it is important that policymakers close glaring loopholes that estate planners exploit to shrink wealthy households’ estate tax liability even further. A particularly popular tactic is to temporarily depress the stated value of a family’s assets when they are transferred to heirs, thereby lowering the amount of estate tax owed. For example, a wealthy couple can place its assets in a family limited partnership, under which the couple transfers those assets to its children but temporarily restricts what the children can do with the assets — and then uses those restrictions to discount the assets (i.e., to claim they are worth less). When the restrictions expire, the heirs end up with the full value of the assets while avoiding substantial estate tax. As tax expert Calvin Johnson has put it:

These are now-you-see-them, now-you-don’t arrangements; that is, the successors will eventually be free from the restrictions . . . and will end up with the full wealth (and power) inherent in the property without the discount. With the discounts, estate planners can get a camel through the eye of a needle and end up with a full camel on the other side.[24]

The Treasury Department has advanced a proposal that targets this loophole and would raise $18 billion over ten years.[25]

Former lawmakers John Edwards and Newt Gingrich received media scrutiny for their apparently aggressive avoidance of payroll taxes.[26] The issue concerns S corporations, which — in lieu of paying corporate income tax — “pass through” their profits (and losses) to shareholders, who pay taxes on those profits at individual income-tax rates. Many S corporation shareholders receive both wages from the S corporation and a share of the S corporation’s profits, but they pay payroll tax only on their wages. This gives them an incentive to underreport the share of their income that consists of wages in order to reduce their payroll tax liability. The health reform law’s increase in the Medicare payroll tax, combined with its exemption of S corporation business income, has increased the attraction of this tax avoidance strategy.

While individuals who are both employees and shareholders of S corporations are supposed to report “reasonable” compensation to themselves, many do not, as various investigations have documented:

- The Government Accountability Office has calculated that in 2003 and 2004, S corporations underreported about $23.6 billion in wage compensation to shareholders, “which could result in billions in annual employment [i.e., payroll] tax underpayments.”[27]

- The Treasury Department’s Inspector General for Tax Administration has concluded that “The S corporation form of ownership has become a multibillion dollar employment tax shelter for single-owner businesses.”[28]

- Separately, analyzing 84 suspect S corporation tax returns, the Inspector General found that shareholders reported average wages of $5,300 and average profit distributions (which are exempt from payroll taxes) of $349,323.[29]

This is unfair to other taxpayers who properly pay their payroll taxes. It also modestly increases the shortfall in the Medicare hospital insurance trust fund. This loophole should be closed. The Joint Committee on Taxation has estimated that earlier proposals to do so would raise roughly $9 billion over ten years.[30]

Many life insurance products offer tax advantages, disproportionately used by wealthy individuals, that have little to do with the underlying insurance aspect of the product. A marketing document from New York Life explains:[31]

The primary purpose of life insurance for individuals and families is to provide a death benefit to help replace lost income and protect loved ones from the financial losses that could result from the insured’s death. However, life insurance — and we are referring here primarily to cash value life insurance — also offers a number of other benefits in the form of tax advantages, many of which are unique to life insurance.

Cash value life insurance is a type of insurance policy that not only pays out upon the policyholder’s death but also accumulates value during the policyholder’s lifetime, because the insurance company invests a portion of the policyholder’s premium payments. In addition to being insurance products, these kinds of policies are investment vehicles. And they enjoy very generous tax advantages: the investment earnings — the so-called “inside buildup” — are not taxed as they accrue or are realized inside the insurance policy. Instead, these investment gains enjoy special tax deferral until the policy is cashed out. Furthermore, the investment gains are never taxed if the proceeds are retained and then paid out upon the policyholder’s death, or if the gains are used to pay the premiums on the life insurance policy (and therefore take the place of premium payments the policyholder would otherwise have to make with after-tax dollars).

This is a more favorable tax treatment than accorded other savings and investment vehicles, such as interest from bank accounts or mutual funds, where earnings are taxed as they accrue or are realized within the fund. This tax treatment also is more favorable than 401(k)s and IRAs receive, because the money in those accounts generally must start to be paid out — and to be taxed as ordinary income — when the accountholder reaches age 70½.[32] In contrast, cashing out a life insurance policy and facing tax on the proceeds is optional.

Moreover, because of the generosity of the tax advantages that they enjoy, 401(k) plans and IRAs face contribution and/or income limits. But there are no such limits on cash value life insurance — wealthy individuals can purchase large policies in which a very large inside-buildup accumulates and still receive the full benefits of this very generous tax treatment.

Further enhancing these tax preferences, the value of these life insurance policies and the amounts that are paid out when the policyholder dies are not considered part of the policyholder’s estate and, with appropriate planning, escape the estate tax — another reason that these policies are popular among extremely wealthy individuals.

The benefits of this tax subsidy indeed go primarily to households at the high end of the income and wealth spectrums. The 10 percent of Americans with the highest incomes owned 54 percent of the value of all cash value life insurance policies in 2010. The lowest-income 50 percent of Americans owned just 5 percent.[33]

This special tax treatment and the concentration of the tax benefits suggest this subsidy is ripe for reform. Recently, some conservative analysts have appropriately suggested that reforming or eliminating this tax break be considered as part of tax reform. [34]

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has outlined an option to treat investment income from life insurance as taxable income. As CBO explains, “life insurance companies would inform policyholders annually of the investment income their accounts have realized, just as mutual funds do now.”[35] According to CBO, this option would raise about $260 billion over ten years. The CBO estimate, however, appears to reflect savings from taxing the inside build up of existing policies, starting right away. Policymakers most likely would phase in the new tax over time or exempt existing policies altogether so that the tax applies only to newly purchased policies, so in practice the revenue savings would be considerably more modest.

Some might object that requiring taxpayers to pay tax on inside buildup income might cause them cash flow problems, as they wouldn’t have direct access to the inside buildup to pay the tax. As the Congressional Research Service notes, however, instead of requiring the taxpayer to pay tax on the inside buildup directly, the insurance company — which has access to the buildup — could pay it on the taxpayer’s behalf.[36] Currently insurance companies are able to withdraw funds from policies to pay premiums and other fees, and policyholders could allow them to make similar withdrawals to make payments for taxes.

The above examples cover just a few of the tax breaks that policymakers should scrutinize and narrow or close. Other examples of tax breaks that policymakers should look at include:

-

Insurance companies’ use of a common tax-avoidance technique in which they use affiliated reinsurers based in Bermuda or other tax havens to shift U.S. profits offshore. The President’s proposal to restrict this activity would save about $13 billion over ten years, according to JCT.

There are, in fact, many features of the tax code that allow multinational corporations to avoid U.S. tax by recording profits earned in the United States as having been earned offshore. President Obama’s fiscal year 2013 budget contains a number of proposals to reform international taxation, which would raise more than $168 billion over ten years[37] and reduce incentives for corporations to shift profits and investments overseas.

- A tax loophole that allows some wealthy private-equity managers to accumulate millions in tax-preferred retirement accounts despite yearly contribution limits[38] by claiming that equity interests transferred into such accounts have only a nominal value. Tax experts have commented that this is how Governor Romney appears to have accumulated an IRA worth about $100 million, as disclosed on his tax returns during his candidacy for President.[39]

- The current tax treatment of derivatives (a type of financial instrument), which allows wealthy taxpayers and derivative traders to avoid or delay taxes on their investment income. House Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI) has recently released proposals that would limit the use of such avoidance techniques.

- The generous tax treatment of corporate-owned life insurance. Businesses can generate substantial tax savings with arrangements that involve taking out insurance policies on their employees or owners. An Administration proposal would raise $7 billion over ten years by restricting some of the most aggressive uses of corporate owned life insurance for tax-avoidance.[40]

Policymakers should combine a well-designed tax-expenditure limitation, such as the President’s 28-percent cap proposal, with reforms of certain tax expenditures that wouldn’t be subject to such a limitation. In so doing, they could raise revenue as part of a balanced deficit reduction package while improving the efficiency and equity of the tax code.