- Home

- Romney Budget Proposals Would Require Ma...

Romney Budget Proposals Would Require Massive Cuts in Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Programs

This report has been superseded by a new version, dated September 24, 2012, that reflects updated data and other information. Click to view the new analysis.

Governor Mitt Romney’s proposals to cap total federal spending, boost defense spending, cut taxes, and balance the budget would require extraordinarily large cuts in other programs, both entitlements and discretionary programs, according to our revised analysis based on new information and updated projections.

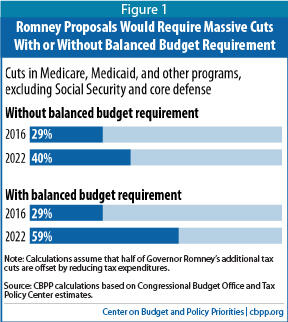

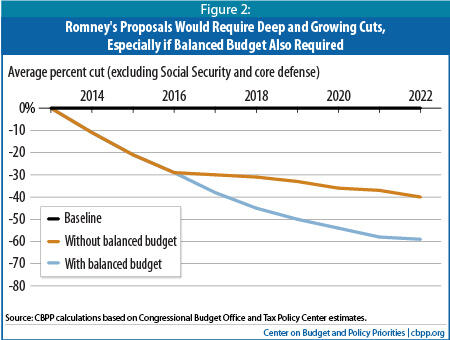

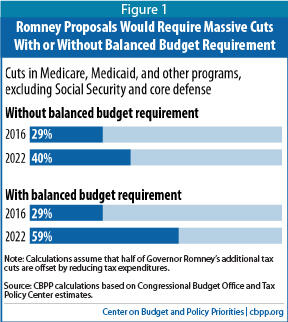

For the most part, Governor Romney has not outlined cuts in specific programs. But if policymakers exempted Social Security from the cuts, as Romney has suggested, and cut Medicare, Medicaid, and all other entitlement and discretionary programs by the same percentage — to meet Romney’s spending cap, defense spending target, and balanced budget requirement — then nondefense programs other than Social Security would have to be cut 29 percent in 2016 and 59 percent in 2022 (see Figure 1). Without the balanced budget requirement, the cuts would be smaller but still massive, reaching 40 percent in 2022.

The cuts that would be required under the Romney budget proposals in programs such as veterans’ disability compensation, Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for poor elderly and disabled individuals, SNAP (formerly food stamps), and child nutrition programs would move millions of households below the poverty line or drive them deeper into poverty. The cuts in Medicare and Medicaid would make health insurance unaffordable (or unavailable) to tens of millions of people. The cuts in nondefense discretionary programs — a spending category that covers a wide variety of public services such as elementary and secondary education, law enforcement, veterans’ health care, environmental protection, and biomedical research — would come on top of the deep cuts in this part of the budget that are already in law due to the discretionary funding caps established in last year’s Budget Control Act (BCA).

Box 1: The Romney Tax Cuts and Our Estimates

Governor Romney has said he would offset an unspecified portion of his proposed tax cuts by reducing tax exemptions, deductions, and other preferences known as “tax expenditures.” Because of Romney’s spending cap (which covers interest payments along with other spending) and his balanced budget requirement, the depth of his required budget cuts depends on the degree to which the cost of his tax cuts would be offset through reductions in tax expenditures. In this analysis, we assume that Governor Romney would offset half of his proposed tax cuts, though we also provide estimates under alternate assumptions. This is a generous assumption: estimates from the Urban Institute-Brookings Tax Policy Center indicate that the Romney tax cuts would cost about $4.9 trillion over ten years. Securing tax-expenditure savings equal to half that amount — about $2.4 trillion — would be extremely difficult, especially since Governor Romney has said he would not increase the low tax rate on capital gains and dividend income and would not cut heavily into tax expenditures for the middle class. Analysts at the Congressional Research Service recently concluded that securing savings of more than $100 or $150 billion a year from tax expenditures is likely to be difficult to achieve.

Governor Romney’s cuts would be substantially deeper than those required under the austere House-passed budget plan authored by Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-WI). Over the 2014-2022 period, Romney would require cuts in programs other than Social Security and defense of $7 trillion to $10 trillion, compared with a little over $5 trillion under the Ryan budget. By 2022, Romney’s cuts would shrink nondefense discretionary spending — which, over the past 50 years, has averaged 3.9 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) and has not fallen below 3.2 percent — to between 1.1 percent and 1.6 percent of GDP.

The Romney Budget Proposals

During his campaign, Governor Romney has made four proposals that would significantly affect the overall level of federal spending, taxes, and the deficit:

- Cap total spending: “Reduce federal spending to 20 percent of GDP by the end of my first term” and “cap it at that level.”[1]

- Increase defense spending: “Set a core defense spending floor of 4 percent of GDP.”[2] “Core defense spending,” as Governor Romney defines it, encompasses 93 percent of the national defense budget function.

- Cut taxes: Continue current tax policy by permanently extending the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts and other tax cuts that are scheduled to expire, further reduce income tax rates by another 20 percent (the top tax rate thus would be 28 percent), eliminate the estate tax, eliminate the taxation of investment tax for people other than those with high incomes, reduce the corporate income tax, and repeal the taxes enacted in the 2010 health reform legislation.[3]

- Balance the budget: “I am planning on getting a balanced budget.”[4]

This paper examines the combined effect of these four proposals, since they interact, to determine the amount of spending that would be available for programs other than core defense.

- If one considers only the first three proposals, total federal spending would equal 20 percent of GDP. Setting core defense spending at 4 percent of GDP would leave 16 percent of GDP for all other federal programs, including Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, as well as for interest on the debt.

- If the budget also had to be balanced, as the fourth proposal states, less than 20 percent of GDP would be available for the entire federal budget. Total spending could not exceed total revenue, and the amount of tax revenue under the Romney proposals would be well below 20 percent of GDP — about 16.8 percent of GDP, if half of Romney’s additional tax cuts are offset by reductions in tax expenditures. Reserving 4 percent of GDP for core defense would leave 12.8 percent of GDP for everything else.

- Governor Romney has said that he would offset the cost of some portion of the tax cuts that go beyond current policy by closing unspecified tax preferences, such as exemptions, deductions, and credits. For reasons detailed below, the main estimates in this paper assume that he would reduce tax preferences enough to offset half of the additional tax cuts. We also provide alternative estimates assuming that he offsets all or none of the additional tax cuts through reductions in tax preferences (see Box 2). The smaller the share of the tax cuts that he offsets, the harder it is to balance the budget, and the deeper Romney’s program cuts must be.

To evaluate the proposals, we also must make assumptions about a few additional elements that Governor Romney has not specified. He has stated that he would limit spending to 20 percent of GDP “by the end of my first term,” by which he apparently means 2016. We also assume that the 4 percent of GDP target for core defense spending would be effective by 2016 and the proposed tax cuts by 2014.

Governor Romney has not pledged to balance the budget by any particular date. Because of this uncertainty, we provide estimates both without and with the balanced-budget proposal. The latter estimates assume that the budget would be balanced by 2022, the end of the current ten-year budget window. Achieving balance earlier would require even steeper cuts in the years immediately after 2016. (See Appendix I for further details about our methodology.)

How Deep Are the Required Budget Cuts?

Table 1 summarizes the program cuts that Governor Romney’s budget proposals would require. The cuts are measured relative to our projection of current budget policy, using the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO’s) latest estimates, which include adherence to the discretionary caps in the Budget Control Act. Thus, the cuts we show in this analysis are in addition to those needed to adhere to those caps.

| Table 1 Program Cuts Required by Romney Proposals, Excluding Social Security and Core Defense | |||

| 2016 | 2022 | 2014-2022 | |

| Without Balanced-Budget Requirement | 29% | 40% | $7.0 trillion |

| With Balanced-Budget Requirement | 29% | 59% | $9.6 trillion |

| Note: Calculations assume that half of Governor Romney’s additional tax cuts are offset by reducing tax expenditures. Source: CBPP calculations based on Congressional Budget Office and Tax Policy Center estimates. | |||

Limiting total spending to 20 percent of GDP, increasing core defense spending to 4 percent of GDP, and enacting Governor Romney’s tax cuts — but not alsobalancing the budget — would still require large cuts in Medicare, Medicaid, and other federal programs.

- The spending cuts would total $688 billion in 2016 alone and $7.0 trillion over the 2014-2022 period.

- If policymakers spread the spending cuts proportionately across all programs other than core defense and Social Security, they would have to cut every other program — including Medicare and Medicaid — by 29 percent in 2016 and 40 percent in 2022.

Implementing the above proposals and also balancing the budget would require even deeper cuts in both entitlement and discretionary programs (outside core defense).

- The dollar cuts would be substantial, totaling $9.6 trillion over the 2014-2022 period.

- The cuts would get deeper with each passing year. (See Figure 2.) If policymakers reduced all programs except defense and Social Security equally, the cuts would grow from 29 percent in 2016 to 59 percent in 2022.

- Although Governor Romney has not proposed specific Medicare policies, it would be virtually impossible to achieve his budgetary objectives while sparing Medicare from substantial cuts. If Medicare as well as Social Security were protected, all other programs — including Medicaid, veterans’ benefits, education, environmental protection, transportation, and SSI — would have to be cut by an average of 40 percent in 2016 and 57 percent in 2022, just to limit federal spending to 20 percent of GDP. If the budget also had to be balanced, all government programs other than defense, Social Security, and Medicare would have to be nearly eliminated: six out of every seven dollars going for them would disappear.

What Share of Governor Romney’s Tax Cuts Might He Offset by Closing Tax Expenditures?

When Governor Romney issued his plan for additional tax cuts on February 22, his campaign stated that an unspecified portion of those tax cuts would be offset by reducing tax preferences, such as exemptions, deductions, and credits — also known as tax expenditures. In a subsequent speech, Romney said:

These [proposed tax cuts] will not add to the deficit. Stronger economic growth, spending cuts, and base broadening will offset the reductions. Middle-income Americans will continue to enjoy tax benefits that favor important priorities, including home ownership, charitable giving, health care, and savings. But there will be some changes in the current deductions and exemptions for higher-income Americans. Those who receive the greatest benefit from rate cuts will see the most significant limits.[5]

Governor Romney has not stated, however, which tax preferences he would reduce or how he would reduce them.

The Tax Policy Center estimates that the Romney tax plan would lose about $480 billion in tax revenue in calendar year 2015, beyond the revenues losses inherent in maintaining current policy (such as continuing all of the 2001 and 2003 Bush tax cuts). Over the 2014-2022 period, that implies a total reduction in revenues of about $4.9 trillion, relative to current tax policy.

Offsetting much of that revenue loss by reducing tax expenditures is likely to prove extremely challenging for several reasons:

- Governor Romney has taken one of the largest tax expenditures — the preferential tax rates on capital gains and dividends — off the table by insisting that they not be raised.

- Most of the total cost of tax expenditures stems from popular tax breaks related to employer-sponsored health insurance, home mortgage interest, retirement savings, state and local taxes, and charitable contributions.

- Governor Romney’s statements indicate that the changes in tax expenditures would apply primarily to “higher-income Americans.” He has not specified what constitutes “higher income,” but once the preferential rates for capital gains and dividends are taken off the table, only a little more than one-third of the remaining tax expenditures accrue to tax filers with incomes above $200,000.[6]

For these reasons, the assumption that Governor Romney could offset even half of his extra revenues losses — or about $240 billion a year — by ending or reducing tax preferences is highly optimistic. More likely, the offset would be far smaller. Analysts at the Congressional Research Service have concluded that “it may prove difficult to gain more than $100 billion to $150 billion in additional tax revenues through base broadening.”[7] The tax-expenditure limitation proposed by well-known economist and former Reagan advisor Martin Feldstein, which conservative Republican legislators like Senator Pat Toomey (R-PA) often cite, would raise just $48 billion in 2015 if it were applied only to taxpayers with incomes above $250,000.[8] Box 2 provides alternative estimates of the spending cuts that would be required if tax preferences were reduced enough to offset all or none of the cost of the additional tax cuts.

Our Calculations Are Consistent with Governor Romney’s

Our calculations are consistent with Governor Romney’s statement in November 2011 that:

As president, I pledge to reduce spending to 20 percent of GDP by the end of my first term. I will cap it at that level. And further, I will put us on a path to a balanced budget and a constitutional amendment that requires the government to spend only what it earns. To reach the 20 percent goal, we’ll need to find almost $500 billion in savings a year in 2016.[9]

Our initial estimate (in January 2012) of the required savings to meet the 20-percent-of-GDP goal in 2016 was only slightly higher than Romney’s own estimate: $537 billion. Our estimate was based on CBO’s budget projections of August 2011, which assumed that more than $1 trillion in budget savings would be achieved by the deficit-reduction “supercommittee” or through the automatic cuts (“sequestration”) that the Budget Control Act called for if the supercommittee failed.

We now estimate that Governor Romney’s 20-percent cap would require $688 billion in cuts in 2016, once 4 percent of GDP is reserved for core defense. Our updated estimate reflects the latest CBO projections, which show a higher level of spending (as a percent of GDP) under current law than the earlier projections did. Our updated estimate also follows the practice adopted in recent months by CBO and other analysts of not including savings from sequestration in the current-policy baseline, from which we measure the needed cuts. Excluding the sequestration savings from the baseline increases the amount of cuts needed to reach Romney’s targets.[10] These two changes together explain the bulk of the difference between our initial and updated estimate of the 2016 cuts. (See Appendix II for details.)

Box 2: What if Governor Romney Offset All — or None — of His Tax Cuts?

This analysis assumes that policymakers would offset half of the revenue losses caused by Governor Romney’s proposed tax cuts (beyond the revenues losses inherent in maintaining current tax policy) by reducing tax expenditures. In reality, the plausible tax offsets are substantially smaller, especially if the reductions in tax expenditures were limited to high-income taxpayers and the most expensive of the tax breaks that high-income taxpayers enjoy — the preferential rates on capital gains and dividends — were retained, as Governor Romney favors.

But what if none of the revenue losses were offset by reducing tax expenditures? Or what if all of them were offset (although Governor Romney does not claim that closing loopholes would offset all his tax cuts)? The table below compares these “all or nothing” alternatives with our assumption of a 50-percent offset.

As it shows, the share of the tax cuts that is offset has a much bigger impact on the size of the required cuts if the budget also has to be balanced, because every dollar of tax cuts would have to be offset by spending cuts. In contrast, if the budget does not have to be balanced, the net size of the tax cuts matters much less, since the 20-percent spending cap, not the level of revenues, would determine the allowable level of spending. The net size of the tax cuts would matter only because the additional interest payments stemming from the revenue losses would have to be offset to fit within the spending cap.

| Size of Program Cuts Under Romney Budget Proposals, Depending on Share of Romney’s Tax Cuts That Is Offset | |||||||

| Cuts Without Balanced Budget Requirement | Cuts With Balanced Budget Requirement | ||||||

| Share of additional tax cuts offset | Share of additional tax cuts offset | ||||||

| All | Half | None | All | Half | None | ||

| Dollar Cuts | |||||||

| 2016 | $675 bil. | $688 bil. | $701 bil. | $675 bil. | $688 bil. | $701 bil. | |

| 2014-2022 | $6.6 tr. | $7.0 tr. | $7.3 tr. | $8.1 tr. | $9.6 tr. | $11.1 tr. | |

| Percentage Cuts | |||||||

| 2016 | 29% | 29% | 30% | 29% | 29% | 30% | |

| 2022 | 37% | 40% | 43% | 47% | 59% | 72% | |

| Note: Additional program cuts to balance the budget by 2022, beyond those needed to cap spending at 20 percent of GDP by 2016, are assumed to be phased in starting in 2017. Therefore, the required cuts in 2016 are the same whether or not the budget is balanced. Source: CBPP calculations based on Congressional Budget Office and Tax Policy Center estimates. | |||||||

Romney Proposals Would Require Even Deeper Cuts than Ryan Budget

Governor Romney’s budget proposals would entail spending significantly more for defense than the House-passed Ryan budget and far less on other programs, especially if the budget is to be balanced by 2022. The Ryan plan itself includes very steep cuts in entitlement and discretionary programs outside the national defense function.

- Under the Ryan plan, core defense spending (the defense budget other than war costs and some relatively small items such as military family housing),[11] would total about $5.7 trillion over the ten-year period 2013-2022. The Romney plan would increase core defense spending to $7.9 trillion. The Ryan plan increases core defense funding modestly relative to the existing BCA caps, but core defense would nevertheless decline to 2.6 percent of GDP by 2022. In contrast, Governor Romney would increase core defense to 4 percent of GDP.

- The Ryan plan would cut entitlement and discretionary programs (outside of core defense and net interest) by $5.2 trillion over ten years.[12] The Romney proposal would cut this spending by between $7.0 trillion and $9.6 trillion, depending upon whether the budget is balanced. Thus, Governor Romney’s ten-year cuts would range from one-third deeper than those in the Ryan budget to almost twice as deep as the Ryan cuts.

What Might These Cuts Mean for Specific Programs?

Table 2 shows the cuts that the Romney proposals would require in selected programs, both with and without a balanced-budget requirement. Even if Governor Romney did not meet his balanced-budget goal, the cuts would be severe.

If policymakers offset half of Romney’s extra tax cuts by reducing tax preferences, reserved 4 percent of GDP for core defense, spared Social Security from cuts over the coming decade, reduced all other entitlement and discretionary programs sufficiently to limit total spending to 20 percent of GDP, and applied the cuts proportionately, those programs would face an across-the-board cut of 29 percent in 2016.

- Medicare would be cut by $185 billion in 2016 and $2.0 trillion from 2014 through 2022. Achieving cuts of this size solely by reducing payments to hospitals, physicians, and other health care providers would threaten beneficiaries’ access to care. Thus, beneficiaries would almost certainly face large increases in premiums and cost-sharing charges.

- Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) would face cumulative cuts of $1.4 trillion through 2022. Repealing the coverage expansions of the 2010 health reform legislation, as Governor Romney has proposed, would achieve more than the necessary savings from Medicaid and other health insurance assistance. But it would leave 33 million people uninsured who would have gained coverage under health reform.[13] (For more about the budgetary implications of repealing the Affordable Care Act, see Box 3.)

Box 3: How Repeal of the Affordable Care Act Affects Our Estimates

A February article in The Atlantic reports, “One Romney adviser maintained the CBPP calculations overstated the breadth of the spending cuts his plan would require because it did not take into account the specific reductions he has proposed, such as the repeal of the health care law.”a In reality, our analysis does take account of his proposal to repeal health reform.

The initial version of this CBPP analysis noted that Governor Romney has proposed repealing the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and that doing so could provide most or all of the cuts that would be required from Medicaid and other health insurance assistance. This remains true. In that case, the cuts needed in other spending programs would be unaffected; our calculations of those cuts would continue to apply.

Alternatively, one could assume that repealing the ACA reduced the size of the required cuts in programs other than Medicaid and health insurance assistance, In that case, other nondefense programs would be cut less — but not by much. For example, as noted earlier, under the scenario in which the budget does not need to be balanced, all programs other than core defense and Social Security — including Medicaid — would have to be cut an average of 29 percent in 2016 and 40 percent in 2022. The average reduction in programs other than Medicaid would drop only modestly, to 24 percent in 2016 and 34 percent in 2022, if the ACA were repealed and Medicaid were cut both by these amounts and by repealing this ACA. Under this scenario, the overall cuts in Medicaid would total 46 percent in 2016 and 56percent in 2022.

a Ronald Brownstein, “Mitt Romney’s Flip-Flop on the Social Safety Net,” The Atlantic, February 3, 2012, http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2012/02/mitt-romneys-flip-flop-on-the-social-safety-net/252557/

- Cuts in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the Food Stamp Program) would throw 13 million low-income people off the benefit rolls, cut benefits deeply — by over $1,800 a year for a family of four — or some combination of the two. These cuts would primarily affect poor families with children, seniors, and people with disabilities.

- Compensation payments for disabled veterans (which average less than $13,000 a year) would be cut by more than one-fourth, as would pensions for low-income veterans (which average about $11,000 a year) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits for poor aged and disabled individuals (which average about $6,000 a year and leave poor elderly and disabled people well below the poverty line).

- Non-defense discretionary spending would be cut by $176 billion in 2016 — and $1.7 trillion through 2022 — in addition to the deep cuts already reflected in the budget baseline as a result of the caps in the BCA and the appropriations bills passed during 2011. This category of spending covers a wide variety of public services such as aid to elementary and secondary education, veterans’ health care, law enforcement, national parks, environmental protection, and biomedical and scientific research.

- As a share of the economy, non-defense discretionary spending would shrink to 2.3 percent of GDP by 2016 and 1.6 percent of GDP by 2022; it would fall to even lower levels if the budget also had to be balanced (see Figure 3). In contrast, spending for this category has averaged 3.9 percent of GDP over the past 50 years and has never fallen below 3.2 percent of GDP during this period.

If anything, these examples may understate the potential effects of Governor Romney’s budget proposals. By 2022, if the budget had to be balanced while taxes were cut, the proposals would require cutting entitlement and discretionary programs other than Social Security and core defense by more than half. And if policymakers offset none (rather than half) of Romney’s tax cuts by reducing tax preferences, they would have to cut these programs by more than 70 percent.

| Table 2 Entitlement and Discretionary Program Cuts Required by Romney Proposals In billions of dollars | ||||||

| Without Balanced-Budget Requirement | With Balanced-Budget Requirement | |||||

| In 2016 | In 2022 | 2014-2022 | In 2016 | In 2022 | 2014-2022 | |

| Percentage cut in all programs except Social Security and core defense | 29.2% | 39.7% | 29.2% | 59.4% | ||

| Total required program cuts | 688 | 1,205 | 6,962 | 688 | 1,805 | 9,633 |

| Cuts to Selected Programs (if all programs except Social Security and core defense are cut by the same percentage) | ||||||

| Medicare | 185 | 369 | 1,978 | 185 | 553 | 2,759 |

| Medicaid and CHIP | 126 | 249 | 1,360 | 126 | 373 | 1,898 |

| SSI, SNAP, child nutrition, and refundable parts of CTC and EITC | 72 | 102 | 654 | 72 | 153 | 896 |

| Federal retirement | 50 | 83 | 491 | 50 | 125 | 679 |

| Veterans’ disability compensation and other entitlement benefits for veterans | 24 | 38 | 225 | 24 | 57 | 309 |

| Total Non-defense discretionary | 176 | 265 | 1,679 | 176 | 396 | 2,308 |

| [resulting level as a percent of GDP] | [2.3%] | [1.6%] | [2.3%] | [1.1%] | ||

| Notes: Calculations assume that half of additional tax cuts are offset by reducing tax expenditures. Program cuts are relative to a baseline that reflects the caps in the Budget Control Act (BCA). Program cuts do not include associated interest savings. Cuts are assumed to be distributed equally across the board except to Social Security and core defense. Source: CBPP calculations based on Congressional Budget Office and Tax Policy Center estimates. | ||||||

Appendix I:

Methods and Assumptions

Approach. The analysis in this paper starts from CBO’s March 2012 baseline budget projections and adjusts those figures to reflect current budget policy, as explained below.[14] It then reduces the revenue numbers in the baseline to account for Governor Romney’s tax proposals, assuming that half of the proposed tax cuts (relative to current policy) are offset by unspecified revenue increases, achieved by limiting tax preferences.

We calculate spending levels under two alternatives: (a) that policymakers limit the size of the total budget to 20 percent of GDP by 2016 while reserving 4 percent of GDP for core defense, and (b) that they also balance the budget through further program cuts by 2022.

Baseline assumptions. We adjust CBO’s March baseline, which is based on scheduled requirements under current law, to reflect the continuation of all expiring tax cuts (both middle-class and upper-income), including relief from the alternative minimum tax through indexing, estate tax relief under current parameters, and the normal “tax extenders.” Our estimates do not assume continuation of the temporary payroll-tax reduction. In addition, we assume that the number of troops engaged in Afghanistan is reduced to 45,000 by 2015. We assume that relief from the scheduled steep reduction in physician reimbursement rates under Medicare’s sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula is continued by freezing current rates. These all are standard assumptions that most budget analysts make in producing a “current policy” baseline, and CBO provides estimates for each of these alternative policies, including the associated changes in debt-service costs.[15]

CBO’s March baseline assumes adherence to the discretionary caps put in place by the Budget Control Act of 2011, which imposes separate caps on defense and nondefense discretionary funding for all years from 2013 through 2021. Our figures therefore start with the resulting, separate defense and nondefense discretionary funding levels. As Appendix II explains, we do not assume that the sequestration scheduled to occur over the 2013-2021 period will occur. We remove the effects of the sequestration from the CBO baseline using CBO’s estimate of its effects, and we use CBO’s interest rate assumptions to calculate the resulting change in debt-service costs.

Proposed tax cuts. The Tax Policy Center estimates that the Romney tax proposals would reduce total tax liability by about $480 billion in calendar year 2015 relative to current policy.[16] That amount equals almost 2.7 percent of GDP (CBO’s estimate of GDP for 2015 is $17.9 trillion). We assume that Governor Romney’s tax proposals will take effect in calendar year 2014, that they will reduce tax liabilities by almost 2.7 percent of GDP in each year, and that there will be a quarter-year lag between the reduction in tax liabilities and the reduction in revenues. Under these assumptions, the Romney tax cuts would reduce revenues by almost $4.9 trillion through 2022 relative to current policy.

However, the Romney campaign has said that these additional tax cuts — those beyond current policy — would be offset through spending cuts, faster economic growth than CBO projects, and reductions in unspecified tax preferences such as exemptions, deductions, and credits. For reasons explained in the text, we assume that half of the revenue losses are offset by reductions in tax preferences, so that the net revenue loss is about $2.4 trillion through 2022.

Calculation of spending cuts. In the final step, we calculate the size of the program cuts that are required, taking into account the resulting debt-service savings, to meet the targets in the two scenarios. We assume that core defense spending will increase in equal steps between 2014 and 2016 until it reaches 4 percent of GDP. Governor Romney has defined “core” defense as covering four types of defense accounts: military personnel; operations and maintenance; procurement; and research, development, testing, and evaluation. Because these defense accounts constitute 93 percent of total non-war funding in the national defense function, our baseline for core defense spending is estimated at 93 percent of the outlays for national defense contained in the CBO baseline that shows the funding levels for these programs under the BCA caps before sequestration.

We assume that Social Security will not be cut within the ten-year budget window, since Governor Romney said in a debate on January 17, “First of all, for the people who are already retired or 55 years of age or older, nothing changes.”[17]

We assume that outlay savings in all other spending programs start in 2014 and grow in equal steps between then and 2016 as necessary to hit the cap on total federal spending of 20 percent of GDP in that year. After 2016, core defense remains at 4 percent of GDP and the cuts in other programs except Social Security grow only as needed to maintain the 20-percent target. We calculate the interest payments consistent with the overall spending and revenue totals. The dollar and percentage cuts we report in this analysis apply to the rest of the budget — that is, to all entitlement and discretionary programs excluding Social Security, core defense, and net interest.

In the scenario in which the budget must be balanced, we maintain core defense at 4 percent of GDP after 2016 but ramp down total spending outside of defense in equal steps each year to reach a balanced budget by 2022. This, too, produces overall spending and revenue totals from which we can calculate the resulting level of interest payments; we then display the cuts that apply to the rest of the budget.

Appendix II:

How Our New Estimates Differ from Our Initial Estimates

An earlier version of this analysis, released on January 23, estimated that increasing defense to 4 percent of GDP and capping overall spending at 20 percent of GDP would require cutting all other programs by $537 billion in 2016, which is similar to the $500 billion that the Romney campaign calculated last fall. We now calculate that $688 billion in cuts would be needed in 2016. Our estimates of the cuts required over the multi-year budget window have also increased.

Our estimates have changed for six reasons, as listed in Table A-1. The biggest change affecting the multi-year totals is simply that we now measure the required cuts through 2022, not 2021. This change in the “budget window” is responsible for the majority of the increase in our estimate of the depth of the budget cuts needed over the multi-year period. The six reasons are as follows:

| Table A-1 Changes in Estimates of Program Cuts Needed Under Romney Proposals | |||

| 2016 | 2014-2022 | ||

| Without Balanced Budget | With Balanced Budget | ||

| January 23 Estimate | $537 bil. | $4.8 tr. | $7.6 tr. |

| Changes: | |||

| Use new CBO baseline | 54 | 0.2 | -0.1 |

| Remove sequestration | 53 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Use “core” defense | 41 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Increase tax cuts | 3 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| Include cuts in 2022 | 0 | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| Delay balance to 2022 | 0 | 0 | -0.6 |

| Current Estimate | $688 bil. | $7.0 tr. | $9.6 tr. |

| Source: CBPP calculations based on Congressional Budget Office and Tax Policy Center estimates. | |||

First, we employ CBO’s revised budget and economic projections of March 13. In the new projections, both spending and revenues are higher, as a percent of GDP, than previously. The higher spending makes it harder to hit Governor Romney’s proposed cap on spending at 20 percent of GDP, so the cuts through 2021 need to be $0.2 trillion larger. But higher revenues make it slightly less difficult to balance the budget.

Second, following other analysts, we have changed our concept of the current-policy baseline. Initially, our baseline reflected the spending reductions from the sequestration scheduled to occur in 2013 through 2021, as a result of the failure of the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction to agree on $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction measures. We now exclude that potential sequestration from our starting point; as a result, deeper cuts are required to meet the target. Sequestration was a fallback mechanism designed to spur the Joint Select Committee and the Congress to act; it was not intended to represent current budgetary policy. CBO does not include sequestration in its “alternative fiscal scenario.”[18] The Concord Coalition and the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget similarly exclude the sequestration savings from their own current-policy baselines.[19] Following this practice, we have removed the potential sequestration from the baseline, adding another $0.4 trillion over ten years to the required program cuts.[20]

Third, we have modified our assumptions about defense spending to reflect new information about Governor Romney’s proposal. Initially we assumed that Governor Romney intended his 4 percent target for core defense to apply to the overall national defense budget function, excluding war costs. But material issued by his campaign explicitly defines core defense as comprising only four types of defense accounts: military personnel; operations and maintenance; procurement; and research, development, testing, and evaluation. This encompasses, most, but not all, of defense spending. As a consequence, the rest of the budget — including non-core defense — is bigger than we had assumed, so deeper cuts are needed to limit it to 16 percent of GDP. Likewise, with higher spending outside core defense than we had assumed, deficits are bigger, so deeper cuts are required to balance the budget. This change in the definition of core defense increases the needed cuts by $0.3 trillion over ten years.

Fourth, after we issued our initial analysis, Governor Romney proposed additional tax cuts beyond continuing current tax policies. If we assume that half of his additional tax cuts will be offset by reducing unspecified tax preferences, the net loss of revenues (and consequent increase in deficits and interest payments) requires $0.1 trillion more in spending cuts to adhere to the 20 percent spending cap and $0.4 trillion more in spending cuts if the budget has to be balanced. (Table 1 shows that the needed budget cuts are much greater if we do not assume policymakers will offset half of Romney’s tax cuts by reducing tax preferences.)

Fifth, we have extended the analysis one year, to 2022, consistent with the new ten-year budget window reflected in CBO’s report. Because the cuts required to adhere to the spending cap or balance the budget get more severe with each passing year, including figures for 2022 significantly increases the required ten-year totals – by $1.2 trillion to adhere to the cap and by $1.8 trillion to balance the budget.

Finally, our first analysis assumed that Governor Romney intended to balance the budget by 2018. We have now delayed that date to 2022, because Romney remains unspecific about the date, and choosing the latest date within the budget window avoids overstating the potential size of the required program cuts. This delay reduces the ten-year cost of balancing the budget by $0.6 trillion.

End Notes

[1] Mitt Romney, Remarks on fiscal policy at the Americans for Prosperity “Defending the American Dream Summit,” November 4, 2011, http://thepage.time.com/2011/11/04/transcript-mitt-romney-delivers-remarks-on-fiscal-policy.

[2] Romney for President, Fact Sheet: Mitt Romney’s Strategy to Ensure an American Century, October 7, 2011, http://www.mittromney.com/issues/national-defense.

[3] Tax Policy Center, The Romney Tax Plan, March 1, 2012, http://taxpolicycenter.org/taxtopics/upload/Romney-Tax-Plan_March-1-2.pdf.

[4] Mitt Romney, I WILL Balance the Budget and Get the Economy Back on Track, February 26, 2012. http://www.mittromney.com/news/press/2012/02/mitt-romney-i-will-balance-budget-and-get-economy-back-track.

[5] Mitt Romney, Remarks in Detroit, Michigan, February 24, 2012, http://www.mittromney.com/blogs/mitts-view/2012/02/mitt-romney-delivers-remarks-detroit-michigan.

[6] CBPP calculations based on estimates from the Tax Policy Center, Table T12-0082, March 26, 2012, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/Content/PDF/T12-0082.pdf.

[7] Jane G. Gravelle and Thomas L. Hungerford, The Challenge of Individual Income Tax Reform: An Economic Analysis of Tax Base Broadening, Congressional Research Service, Report R42435, March 22, 2012.

[8] Robert Greenstein, Chye-Ching Huang, and Chuck Marr, Can Governor Romney’s Tax Plan Meet Its Stated Revenue, Deficit, and Distributional Goals at the Same Time? Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 2, 2012, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/3-2-12tax.pdf.

[9] Romney, Remarks on fiscal policy.

[10] Continuing to assume sequestration in the baseline would reduce the cuts needed to adhere to the 20-percent-of-GDP cap in 2016 and later years or to balance the budget. Excluding sequestration from the baseline, we estimate that program cuts of 29 percent would be needed in 2016 to meet Governor Romney’s promises; if sequestration were included in the baseline, the cuts needed beyond sequestration would be 27 percent.

[11] The Ryan budget does not separate core defense, as Governor Romney defines that term, from other defense activities. But it does specify amounts for the total national defense function. See Committee on the Budget, U.S. House of Representatives, Report to Accompany H. Con. Res. 112, March 23, 2012. Core defense, as Romney defines it, includes military personnel; operations and maintenance; procurement; and research, development, testing and evaluation. The budget accounts covering these parts of the defense budget constitute 93 percent of non-war defense funding. Based on this information, we estimate the amount that the Ryan budget would spend on core defense, excluding war costs.

[12] Based on Committee on the Budget, U.S. House of Representatives, Report to Accompany H. Con. Res. 112. The figures cited represent total outlays for all budget functions other than national defense and net interest, plus an estimate for non-core defense needs, as explained in the previous footnote.

[13] Congressional Budget Office, Updated Estimates for the Insurance Coverage Provisions of the Affordable Care Act, March 2012, http://cbo.gov/publication/43076.

[14] Congressional Budget Office, Updated Budget Projections: Fiscal Years 2012 to 2022, March 2012, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/March2012Baseline.pdf.

[15] CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook, January 31, 2012, Table 1-6, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/01-31-2012_Outlook.pdf.

[16] Tax Policy Center, The Romney Tax Plan, p. 2.

[17] Transcript, Fox News Channel and Wall Street Journal Debate in South Carolina, January 17, 2012, http://foxnewsinsider.com/2012/01/17/transcript-fox-news-channel-wall-street-journal-debate-in-south-carolina/.

[18] Congressional Budget Office, Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2012 to 2022, page 21, http://www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=12699.

[19] Concord Coalition, The Concord Coalition Plausible Baseline, http://www.concordcoalition.org/concord-coalition-plausible-baseline; Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, Analysis of CBO’s Budget and Economic Projections and CRFB’s Realistic Baseline, January 31, 2012, page 7, http://crfb.org/sites/default/files/crfb_analysis_cbo_projections.pdf.

[20] CBO estimates that the outlay savings from the scheduled sequestration would be $1.0 trillion over the 2013-2021 period. Some $0.4 trillion of that total would come from nondefense programs; the rest would come from defense and interest.