Republican legislation that was introduced in the Senate by Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and Finance Committee ranking member Orrin Hatch (R-UT) and in the House by Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI) would establish requirements for tax-reform legislation that could generate higher deficits and substantially shift tax burdens from high-income to low- and moderate-income taxpayers.[1]

The House version, on which the House will vote this week, would require congressional tax-writing committees to produce legislation next year that: 1) cuts the top individual tax rate from its current 35 percent level (and the 39.6 percent to which it’s slated to return on January 1) to 25 percent and cuts most other tax rates as well; 2) cuts the top corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 25 percent and eliminates corporate taxes on foreign profits; and 3) eliminates the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), which was established to ensure that all high-income taxpayers pay at least some minimal amount of tax. The House bill also provides a “fast track” process for House and Senate consideration of legislation that meets the bills’ requirements.

Policymakers broadly agree on the need to address long-term budget deficits, and they increasingly recognize the need for a balanced approach that includes revenue increases. The House and Senate bills represent a significant step backward in this regard. They would:

-

Fail to require any deficit reduction and, in fact, invite higher deficits. The House bill calls for tax-reform legislation that would produce only about the same level of revenue as if policymakers made all of President Bush’s tax cuts permanent,[2] while the Senate proposal calls for tax changes that would either be “revenue neutral or result in revenue losses” (emphasis added) compared to a continuation of current policy.

Given the need for additional revenue to help address mid- and long-term deficits, a requirement that tax reform be revenue neutral would be highly problematic because it would lock in a permanent tax-rate structure and scale back “tax expenditures” (deductions, credits, and other preferences) without producing any deficit reduction.

The scheduled expiration of the Bush tax cuts on December 31 (and policymakers’ upcoming decisions on whether to extend them) and the potential to curb tax expenditures provide the only two realistic opportunities now available to secure a significant revenue contribution to deficit reduction. By creating a process to establish a permanent tax-rate structure and scale back tax expenditures without reducing the deficit, the House and Senate bills not only would produce no savings now but also would effectively take revenues off the table for deficit reduction for a number of years to come.

The Senate bill’s language that allows for tax reform to generate revenue losses goes even further, effectively inviting deficit-increasing tax cuts. It would allow tax-reform legislation that loses substantial revenues and thereby increases deficits, while barring legislation that raises revenues and shrinks deficits.

- Cut individual income tax rates well below the already unaffordable Bush levels. The House version mandates a top rate of 25 percent (as well as a lower 10 percent bracket). The Senate proposal is less specific, calling for a top rate “significantly below” the current 35 percent rate and for a proportional cut in other tax rates. Both versions call for eliminating the AMT. Not only would these changes disproportionately benefit high-income households, they would be extremely costly as well. For example, the Tax Policy Center (TPC) has estimated that the proposal reflected in the House bill to create two tax brackets — 25 percent and 10 percent — and eliminate the AMT would lose $3.2 trillion in revenue over ten years.[3]

- Slash the top corporate tax rate and eliminate taxes on foreign profits. While calling for revenue-neutral corporate tax reform, the House and Senate bills would cut the top corporate tax rate to no more than 25 percent (from the current 35 percent), a change that, by itself, would cost $1.1 trillion over ten years, TPC estimates.[4] The congressional Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates that even if policymakers eliminated nearly all major corporate tax expenditures and devoted all of the revenue to paying for rate cuts, they could reduce the corporate top rate only to about 28 percent.[5] The bills also call for setting the corporate tax rate on foreign profits at zero by adopting a “territorial” tax system (as discussed below).

- Not identify specific measures to broaden the tax base. While the House bill specifies that both the top individual and corporate tax rates must fall to 25 percent and the Senate bill moves in a similar direction, both bills are vague about the tax expenditure reforms that supposedly would offset the cost of their very large rate cuts. The House bill calls only for “broadening the tax base,” the Senate bill only for “reducing the number of tax preferences.” That raises the risk that lawmakers will reduce tax rates but not follow through on curbing expenditures, thus swelling budget deficits.

-

Not protect low- and moderate-income Americans. The Senate bill requires only that tax reform “retain a progressive tax code,” meaning that the tax reform legislation itself could be regressive so long as doesn’t entirely eliminate the tax code’s overall progressivity. (Moreover, the proposal does not define “progressivity;” some lawmakers have adopted dubious definitions to claim, for example, that the Bush tax cuts are progressive.) The House bill lacks even this minimal requirement.

The proposals thus provide no protection from policy changes that would shift tax burdens down the income scale by giving large net tax cuts to high-income individuals and net tax increases to low- and moderate-income families. That’s because the tax rate cuts that the bills call for would be very regressive and give their biggest tax cuts by far to people at the top, while curbs on tax expenditures could cause significant tax increases for low- and middle-income families. That’s especially true if, as many Republicans favor, policymakers protect the primary tax expenditure that benefits people at the top — the low top rate on capital gains and dividend income — while substantially cutting tax expenditures on which ordinary families rely.

The bills’ absence of a firm deficit-reduction requirement, combined with their requirements for costly and regressive tax rate cuts, illustrate the danger that the tax reform process could become a trap, producing legislation that boosts deficits, reduces tax code progressivity, and widens after-tax income inequality.[6]

The bills’ instructions for tax reform pose serious problems for both fiscal responsibility and tax fairness.

The House bill’s instructions are the more detailed of the two. The tax-rate structure that it would require — with a 25 percent top rate — would cost $2.5 trillion over ten years, according to TPC.[7] Its requirement to end the AMT would cost another $670 billion, compared to a continuation of current policy (that is, on top of the cost of assuming all of the Bush tax cuts are made permanent and AMT relief is continued).[8] Cutting the corporate rate to 25 percent would cost another $1.1 trillion. [9] All of these costs would come on top of the cost of making the Bush tax cuts permanent, which amounts to $3.8 trillion over ten years, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).[10]

The Republican bills lack clear direction on which tax expenditures policymakers should scale back or eliminate to pay for their costly rate cuts. As noted, the House bill includes only a vague call for “broadening the tax base,” while the Senate bill’s only instruction in this area is for policymakers to “reduc[e] the number of tax preferences.”

Many tax expenditures are popular, used by a wide cross-section of taxpayers, and politically difficult to scale back significantly. Moreover, the tax rate cuts that both bills would require would shrink the revenue gains from certain tax-expenditure reforms. The value of many of the largest tax expenditures (like those for mortgage interest and employer-provided health insurance) is directly tied to the tax rate: the lower the tax rate, the lower the value of these deductions and exclusions. So, if policymakers cut tax rates, then reductions in deductions and exclusions would generate substantially less revenue. (See the box on page 5.)

TPC recently demonstrated the difficulty of cutting tax expenditures enough to pay for large tax rate reductions.[11] TPC began by assuming an across-the-board 20 percent cut in individual tax rates below the Bush rates and an end to the AMT. TPC then selected a group of the largest tax expenditures (as well as many smaller ones) — including those for mortgage interest, employer-provided health insurance, charitable giving, and state and local taxes — and asked how deeply policymakers would have to cut these large, popular tax expenditures to pay for the 20 percent rate cut and AMT elimination. The answer was a stunning 72 percent. Politically speaking, cuts of this size are extremely unrealistic.

The Republican bills’ instructions regarding corporate taxation are problematic as well. The bills call for revenue-neutral corporate tax reform and a top corporate tax rate of 25 percent. But JCT estimates show the virtual impossibility of cutting corporate tax breaks enough to pay for such a large rate cut.[12] JCT has estimated that even if policymakers eliminated nearly all major corporate tax expenditures — including accelerated depreciation, the research and experimentation credit, the deduction for domestic manufacturing, and all energy tax subsidies — that would pay for reducing the top rate only to 28 percent.

Cutting Tax Rates Shrinks Revenue Gains from Tax Expenditure Reforms

The value of many of the largest tax expenditures is tied to the tax rates, so tax rate cuts like those envisioned in the House and Senate Republican bills would reduce the value of those tax expenditures — and hence the revenue generated from shrinking or eliminating them. Consider this example:

- Mr. Jones has a large amount of income taxed in the top (35 percent) tax bracket and pays $30,000 in mortgage interest annually. His tax subsidy from the mortgage interest deduction thus is $10,500 ($30,000 times 35 percent).

- Suppose Congress caps the mortgage interest deduction at 20 percent of a taxpayer’s annual mortgage interest payments. That reduces Mr. Jones’ tax subsidy from $10,500 to $6,000 ($30,000 times 20 percent), thereby raising federal revenue by $4,500.

- Suppose instead that Congress first cut Mr. Jones’s tax rate to 28 percent. His mortgage interest deduction would be worth $8,400 ($30,000 times 28 percent) rather than $10,500.

- If Congress then capped the mortgage interest deduction at 20 percent, it would lower his subsidy to $6,000, so the revenue gain from capping the deduction would be $2,400 ($8,400 minus $6,000).

- In this example, a 20 percent reduction in the tax rate (from 35 percent to 28 percent) reduces, by nearly half, the savings from imposing the cap on the mortgage interest deduction.

Furthermore, many of the tax breaks that JCT identified have strong support among lawmakers, making their elimination quite unlikely. What’s more, even the scenario JCT outlined would not be revenue neutral over the longer term. JCT cut the rate to 28 percent in a deficit-neutral manner only by relying on offsets that raise large amounts of revenue over the next decade but much less in later decades, as JCT itself notes. By 2021 — the last year of the ten-year period that JCT examined —cutting the corporate rate to 28 percent and eliminating major corporate tax expenditures would cost $11 billion and revenue losses would continue to grow after that, adding to long-term deficits.

To be sure, policymakers could raise additional revenues from firms to help pay for the proposed corporate rate cut in ways other than by eliminating virtually all major corporate tax expenditures. For instance, limiting the interest deduction on the debt financing of investments or taxing large pass-through entities in the same way as corporations present two such possibilities. Such changes, however, would likely be as difficult politically as cutting “traditional” corporate tax breaks such as the research and experimentation tax credit.

Therefore, even with optimistic assumptions that are not politically realistic, policymakers would be hard-pressed to cut the corporate tax rate below 28 percent without increasing the deficit. Nevertheless, the House and Senate bills require a corporate rate of no more than 25 percent.

The one corporate tax expenditure to which the Republican proposals specifically allude is corporations’ current ability to defer taxes on their foreign profits until they are “repatriated.” (In contrast, corporations must pay taxes on their domestic profits as they earn them.) This tax expenditure is a big reason why the tax code is now tilted toward foreign over domestic profits. The House and Senate bills call for a “territorial” tax regime, a little-understood concept that many multinational corporations are now promoting, under which the government would tax only the domestic share of a multinational company’s income.

A territorial regime would exemptforeign profits from U.S. corporate taxes altogether, thereby reducing the share of corporate profits that is taxable and further encouraging U.S. firms to shift jobs and investment overseas. The Congressional Research Service’s Jane Gravelle has explained:

[moving to a territorial system] would make foreign investment more attractive. That would cause investment to flow abroad, and that would reduce the capital which workers in the United States have, so it should reduce wages. A capital flow reduces wages in the United States [and] increases the wages abroad.[13]

Tax-rate cuts like those envisioned by the House and Senate bills would almost certainly be regressive.

The House bill requires that tax-reform legislation establish two individual income tax rates — one at no more than 25 percent and the other at 10 percent — and repeal the AMT. This appears to mirror the tax-rate reductions reflected in the budget plan the House approved in March (sometimes referred to as the “Ryan budget”); the House budget plan similarly called for two tax brackets of 25 percent and 10 percent, as well as AMT repeal (along with corporate tax reform and repeal of the tax provisions of the Affordable Care Act).

TPC found[14] that the tax-rate reductions and other changes in the House budget would[15] provide an average tax cut of $265,000 in 2015 to people who make over $1 million a year, while providing an average tax cut of just $510 to people making between $40,000 and $50,000. TPC also reported that these tax cuts would reduce after-tax income by 12.5 percent for people with incomes over $1 million, but 1.3 percent for those with incomes in the $40,000-to-$50,000 range.

As a result, the reductions in tax rates and related tax changes would be highly regressive. The House budget plan also called for offsetting reductions in tax expenditures but failed to specify a single tax expenditure to close or narrow. As various analyses have explained, though, it would be nearly impossible to design and secure congressional approval for tax-expenditure changes so radical and massive that they could offset more than a portion of the losses in revenue and the increase in regressivity that would result from these deep tax-rate cuts.

Table 1

Average Tax Change and Percent Change in After-Tax Income in 2015 Under the Tax-Rate Reductions and Other Specific Tax Provisions of the House Budget Resolution |

| Income | Average Tax Change | Percentage Change in

After-Tax Income |

| Less than $10,000 | $112 | -2.0% |

| $10-$20K | $193 | -1.2% |

| $20-30K | $58 | -0.2% |

| $30-$40K | -$209 | 0.6% |

| $40-$50K | -$510 | 1.3% |

| $50-$75K | -$975 | 1.8% |

| $75-$100K | -$1,692 | 2.3% |

| $100-$200K | -$2,818 | 2.5% |

| $200K-$500K | -$11,089 | 4.8% |

| $500K-$1M | -$47,040 | 8.8% |

| More than $1M | -$264,970 | 12.5% |

Note: Compared to current policy; does not include plan’s reductions in unspecified tax expenditures.

Source: Urban Brookings Tax Policy Center -- Table #T12-0126 |

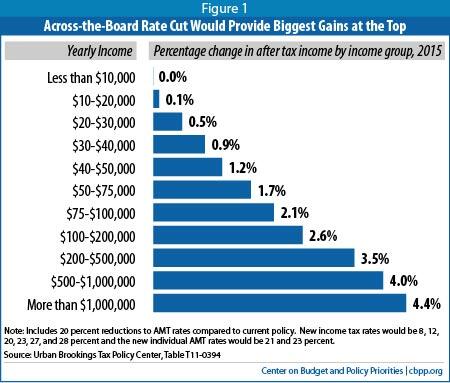

The instructions for tax reform in the bill that Senators McConnell and Hatch introduced would also almost certainly lead to regressive policies. The Senate bill calls for all income-tax rates to be cut proportionally, and for the rates to be set significantly below the Bush rates. Across-the-board reductions in income-tax rates are inherently regressive. A TPC analysis found, for example, that if all tax rates were cut by 20 percent, after-tax incomes would increase by more than two and a half times as much in percentage terms for people making over $1 million a year as for those making $50,000 to $75,000.[16] (See Figure 1; these figures do not include repeal of the AMT, which the Senate bill also calls for and which would also be regressive.)

On the corporate side, both the House and Senate bills call for a top tax rate of no more than 25 percent — a substantial cut from the current 35 percent. They state that corporate tax reform should be revenue neutral but offer no details on how to offset the cost of their very large rate cuts; as explained above, curbing corporate tax expenditures enough to offset the cost of cutting the rate to 25 percent would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, for policymakers to accomplish.

Cutting the top corporate rate to 25 percent thus would likely result in fewer overall corporate tax revenues. While economists disagree about who really pays the corporate tax — how much is borne by owners of capital and how much by labor — the estimates by non-partisan organizations such as the Congressional Budget Office and TPC all show the corporate income tax to be progressive.[17] Shrinking the corporate tax burden would therefore likely have regressive effects.

Like some other recent tax proposals to “lower the rates and broaden the base,” the Senate and House Republican bills place their top priority not on deficit reduction but on costly and regressive tax-rate cuts. These proposals would likely lead to larger budget deficits, a less progressive tax code, and greater inequality in after-tax incomes.