Allowing the top two marginal tax rates to return to pre-2001 levels as scheduled next year would affect very few small businesses, a recent Treasury Department study found.[1] The study shows that only 2.5 percent of small business owners face the top two rates.

The claims that allowing the Bush tax cuts for high-income people to expire would seriously harm small businesses rest on an exceedingly broad, and misleading, definition of “small business.”[2] The definition is so broad, in fact, that under it, both President Obama and Governor Romney would count as small business owners — as would 237 of the nation’s 400 wealthiest people.[3]

Charges that any tax increases on people making over $1 million a year, such as Senator Sheldon Whitehouse’s proposal to implement the “Buffett Rule,” would inflict injury on many small businesses rest on the same misleading definition of small businesses.[4]

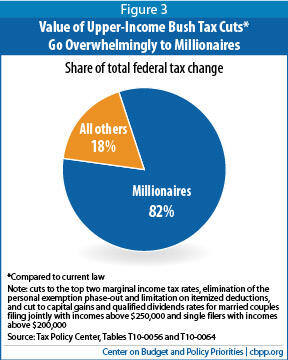

Contrary to these claims, an extension of the high-income Bush tax cuts would, in essence, constitute a massive tax cut for very wealthy individuals who overwhelmingly aren’t small business operators. Analysis by the Urban Institute-Brookings Tax Policy Center finds that extending the tax cuts for people over $250,000 of income ($200,000 for single filers) would overwhelmingly benefit the highest-income taxpayers: 82 percent of the value of the tax cut would flow to filers with more than $1 million in adjusted gross income, who would get an average tax cut of $164,000 a piece.

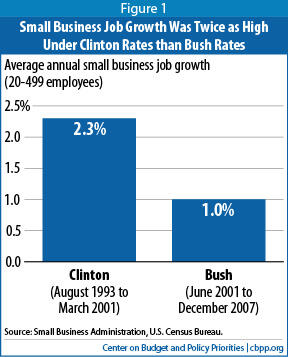

[5] The arguments against allowing the high-end tax cuts to expire on schedule echo those made against President Clinton’s proposed 1993 tax increases, which set marginal rates at the levels to which they are set to return when the Bush rate cuts expire. Critics claimed at the time that those tax increases would seriously harm economic growth and even send the economy back into recession. As it turned out, job creation and economic growth proved significantly stronger following the 1993 tax increases than following the 2001 Bush tax cuts. Further, small businesses generated jobs at twice the rate during the Clinton years than they did under the Bush tax code (see Figure 1).

The frequently cited claim that letting the high-income tax cuts expire would seriously harm small businesses because “roughly half of the income of small businesses” is taxed at the top two tax rates relies on a highly exaggerated definition of small business owner[6] . This definition includes any taxpayer who receives any income from any “pass-through” entity (that is, an entity that does not pay corporate income tax on its profits but instead passes them through to its owners, who pay tax at the individual rates). This definition is severely flawed:

- It includes many entities that are not “businesses.” Many pass-throughs are “not engaged in business activity as it is traditionally understood,” the recent Treasury analysis explains.[7] For example, taxpayers can create pass-through entities simply as a vehicle to invest in other businesses. They also can create pass-through entities simply as a way to sell their own personal services (rather than to employ any other person), in which case the taxpayer is acting more as a contract employee than as what most people would consider a business owner. Pass-through income also includes income from the incidental rental of a vacation home; under the broad definition, a several-week rental of a vacation home can cause a banker or corporate executive to be categorized as a “small business owner.”

- It includes people who have no involvement with the running of the business. Many taxpayers who receive pass-through income are simply passive investors. For example, a wealthy individual who has invested in a real estate partnership but has no involvement in decisions about what property to invest in or to sell qualifies as a small business owner under the overly broad definition.

- It includes people who receive even a tiny proportion of their income from a small share of a small business. Even if a taxpayer received just $1 of his or her multi-million-dollar income from a pass-through business he or she had invested in, the taxpayer would be considered a small business owner under the broad definition.

- It includes many entities that are not small. S corporations are a type of pass-through entity because they do not pay corporate income tax; the shareholders instead pay taxes on the firm’s profits at their individual tax rates. But many S corporations are not small. In 2009, only 0.3 percent of S corporations had incomes exceeding $50 million, but they accounted for 35 percent of all S corporation income.[8] Two examples of large S Corporations are the media giant Tribune Co.[9] and the industrial firm AMSTEAD Co., which according to Forbes had revenues of $2.8 billion in 2007.[10]

The misleading nature of this broad definition of small business is perhaps most starkly highlighted when one looks at the IRS-published data on the highest-income people in the country. Of the top 400 people — who received $19.8 billion in S corporation and partnership net income in 2009 — 237 would be counted as small businesses. These individuals, whose incomes averaged more than $202 million in 2009, hardly represent what most Americans think of when they hear the term “small business owner.”

Under this definition, both President Obama and Governor Romney would have counted as small business owners in 2011. President Obama’s adjusted gross income of $789,674 included $441,369 in book royalties (net of commissions);[11] royalties are reported as pass-through income, so President Obama would count as a small business owner. Governor Romney’s adjusted gross income of $20 million included $110,000 in author and speaking fees reported as pass-through income, so he, too, would count as a small business owner.

The recent Treasury study tries to overcome the first three of the shortcomings listed above by defining a small business as one that has at least $5,000 in tax deductions for activities that are considered “businesslike” — such as expenses related to employees, inventories, office supplies, and rent — and has income and deductions of less than $10 million.[12] It defines a small business owner as someone who derives at least 25 percent of his or her adjusted gross income from a small business. Under this much more reasonable definition, it is evident that allowing the upper-income Bush tax cuts to expire on schedule, far from constituting a tax hike on large numbers of small businesses and their owners, would prevent a windfall for the highest-income Americans in the face of unsustainable budget deficits.

- Very few small business owners face the top two tax rates. The Treasury study shows that only 2.5 percent of small business owners, and 7.9 percent of filers with any income from small businesses that employ people, face the top two tax rates. Only 0.5 percent of small business owners, and 3.3 percent of filers with any income from small businesses that employ people, make $1 million or more per year.

- Very little of high-income taxpayers’ income comes from small businesses. Only 7.6 percent of the income going to taxpayers facing the top two marginal tax rates comes from small businesses, properly defined. Only 5.6 percent comes from small businesses that employ people. (Just 3.3 percent of the income going to millionaires comes from small businesses and goes to small business owners; 2.5 percent comes from small businesses that employ people.) Extending the Bush tax cuts for high-income people would give them a large windfall on what overwhelmingly is not small business income.

- High-income people earn a much smaller share of small business income than some have claimed. As noted, claims that half of small business income is taxed at the top two tax rates[13] (or that a millionaire surtax would affect 34 percent of small business income[14] ) treat all pass-through income as small business income, a poor measure. The Treasury data show that taxpayers who face the top two tax rates account for 29.5 percent of small business income that goes to small business owners (and 38.3 percent of income from small businesses that employ people). And in any event, as discussed below, the economic case for cutting taxes on all of the income of high-income taxpayers on account of their small business income is flawed: there is no good evidence that doing so helps small businesses to grow or to hire more employees.

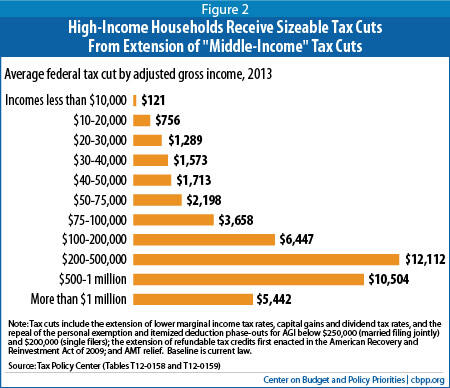

Furthermore, as Figure 2 shows, under the proposal to allow tax cuts on income above $250,000 ($200,000 for single filers) to expire, taxpayers in the top two brackets would still keep sizeable tax cuts on the first $250,000 of their income ($200,000 for single filers).

As the foregoing data indicate, tax rate cuts for high-income people are a poorly targeted way to deliver tax cuts to small businesses. But even setting that aside, claims that small businesses need an extension of the Bush-era tax rates to thrive imply that small business owners will sharply curtail their business activities if tax rates go up. Economic theory and evidence do not support such assertions.

With the economy still suffering from inadequate demand, policymakers should focus on what small businesses (and large businesses) need most: more customers. Until they see a pickup in sales, businesses with excess capacity are unlikely to use the proceeds from any tax cuts to hire more workers or expand capacity further.

This is why CBO, even as it has noted that some businesses would profit from an extension of the current top tax rates, rejected the argument that Congress should extend these tax cuts to create jobs in a weak economy: “increasing the after-tax income of businesses typically does not create much incentive for them to hire more workers in order to produce more, because production depends principally on their ability to sell their products.”[15]

Providing more disposable income to households that are working hard to make ends meet is the best way to increase demand in a weak economy. Such households are the ones most likely to spend immediately (rather than save) a large share of whatever income they receive. As businesses see greater sales, they are more likely to hire additional workers and increase their purchases from suppliers. The spending thus ripples through the economy, further boosting demand — the “multiplier” effect.

Tax cuts for high-income individuals are much less cost-effective at boosting economic growth. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that extending the upper-income Bush tax cuts for one year would cost about $40 billion in 2013. CBO estimates show this would likely boost output by much less than $24 billion in 2013.[16] The $24 billion figure uses CBO’s calculations of the multiplier effect for the extension of all the Bush tax cuts. CBO does not provide a multiplier for the upper-income tax cuts alone, but CBO notes that because higher-income households would spend a smaller fraction of any increase in their after-tax income than the typical household would, extending the tax cuts for upper-income taxpayers would deliver less “bang-for-the-buck” — i.e., less economic activity per dollar of cost to the Treasury — than extending the tax cuts for other households.

As CBO says in its analysis of how different policies affect spending in a weak economy, allowing the rate increases for the top brackets to go into effect while extending the tax-rate cuts for other households would be “more cost-effective in boosting output and employment in the short-run” — i.e., would do more to increase growth and jobs per dollar of cost — than extending the tax cuts for everyone, including high-income households. The reason is that high-income households would spend a smaller fraction of any increase in their after-tax income than the typical household would.

Policymakers have channeled a large volume of tax breaks to small businesses and their owners, primarily on the assumption that tax policy strongly affects small business job creation. But the evidence is neither clear nor compelling that once the economy recovers, individual tax rates strongly influence high-income business owners’ decisions about whether to invest money in expanding their businesses.

As the Congressional Research Service (CRS) notes, cutting business owners’ individual tax rates creates no direct incentive for them to hire more workers because their workers’ wages are entirely tax deductible.[17] In a strong economy with little or no excess unemployment, the main constraint on job creation is the lack of available labor. There is no sound theory or evidence for the idea that individual tax cuts for business owners would increase the supply of labor. And while sound investments can increase productivity and hence wages (rather than the number of jobs), there is no sound evidence, either, that individual tax cuts for business owners cause them to invest more in their businesses.

Cutting the personal tax rates of high-income owners might improve their cash flow, but this should not have a large effect on hiring when the economy is not in recession and owners have access to cash from bank loans and other sources to fund any investments that would be profitable. (In a recession, as discussed above, such tax cuts have low bang-for-the-buck because businesses’ main problem is lack of consumer demand, not lack of cash.)

Cutting tax rates of high-income owners might lead some of them to increase their work hours in the business (in cases where they actually do work in the business) by raising their after-tax gains from work. On the other hand, such tax cuts might lead other owners to work less, because it would take less work effort at the lower tax rates to maintain their after-tax standard of living. Studies show that overall, cutting the tax rates of high-income taxpayers (within the ranges that policymakers are debating) has a negligible net effect on the amount that they work (with the effects just described essentially cancelling each other out).[18]

Only one study directly addresses the question of whether cutting the marginal tax rates of existing small business owners leads them to hire more workers. That study, by Douglas Holtz-Eakin and others, contends that an increase in small business hiring followed the deep cuts in tax rates from the 1986 tax reform. But CRS has noted that the study may overstate the extent to which high-income entrepreneurs respond to tax changes, in part because it fails to control adequately for the ways in which high-income taxpayers’ behavior is likely to differ from that of other taxpayers. CRS cautions that “given only one study, it is premature to conclude that raising taxes of the owner would decrease hiring in existing firms.”[19]

The experience of recent decades also contradicts predictions made when the 1993 budget reconciliation legislation (which instituted larger tax rate increases on high-income taxpayers than those now under discussion) was being considered that those rate increases would seriously harm small businesses and economic growth. Instead, the economy flourished in the 1990s. As Figure 1 shows, small business job growth was twice as strong in the 1990s when the top individual income tax rate was 39.6 percent as in the 2001-2007 economic recovery when the top rate was 35 percent.

William Gale, co-director of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, has noted that “the effective tax rate on small business income is likely to be zero or negative, regardless of small changes in the marginal tax rates,” because of the very valuable array of tax subsidies that small businesses receive (emphasis added).[20] As CRS notes, the subsidies with the broadest reach include, in addition to the taxation of small firms as passthrough entities, “the expensing allowance for equipment …, the exemption of some small corporations from the corporate alternative minimum tax, cash basis accounting, and the exclusion from taxation of capital gains on the sale or disposition of certain small business stock.”[21]

There is an emerging consensus among economists that young small firms — not small firms in general — are particularly important “job creators.” A 2010 study finds no systematic relationship between firm size and job growth, after controlling for firms’ age.[22] It thus is important to distinguish between startup businesses, which the study finds “contribute substantially to both gross and net job creation” (as well as to gross job destruction when they fail, as many startups do), and other small businesses, which on average generate no more net job growth than do larger businesses.[23]

Similarly, as CRS notes, recent research “suggests that small businesses contribute only slightly more jobs than other firms relative to their employment share. Moreover, this differential is not due to hiring by existing small firms, but rather to startups, which tend to be small.”[24]

And startups will not benefit much from lower marginal tax rates or additional tax breaks (unless they can be received as a refund in cash) unless the firms are immediately profitable, because firms that are not profitable do not pay taxes.

Furthermore, as CRS has noted, while taxes may reduce the after-tax return to investment of business owners, they also may encourage risk-taking and entrepreneurship by reducing business lossesas well as gains and thus acting like a form of “insurance for risky investment.”[25] CRS has explained that “earnings tend to vary more among the self-employed, and higher tax rates reduce the variance of earnings.” That is, federal taxes may in effect cause the government to function as a partner in the business venture, “bearing some of the risk and receiving some of the return.”[26]

Extending the tax cuts on incomes in excess of $250,000 would add nearly $1 trillion to deficits over 2013 to 2022, but benefit only about the highest-income 2 percent of households.[27] The biggest benefits would flow to the very highest-income people: as Figures 3 shows, more than 80 percent of the value of the upper-income tax cuts would go to people who make more than $1 million a year.

As discussed above, very few of the high-income taxpayers who benefit from the upper-income tax cuts are in fact “small businesses” in the way the term is commonly understood. Moreover, there is no good evidence that cutting the taxes of small business owners is an effective way to boost hiring or growth in either the short run or the long run.

Policymakers ought not let myths and lobbyists’ slogans regarding high-income taxpayers and small businesses drive them toward a costly policy that would add heavily to deficits while delivering little economic benefit.