SNAP Plays a Critical Role in Helping Children

End Notes

[1] Unpublished CBPP analysis of March 2011 Current Population Survey. For a discussion of the method used, see Arloc Sherman, “Poverty and Financial Distress Would Have Been Substantially Worse in 2010 Without Government Action, New Census Data Show,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 7, 2011, http://https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/11-7-11pov.pdf

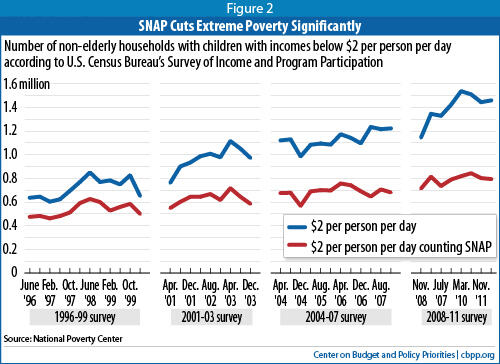

[2] H. Luke Schaefer and Kathryn Edin, “Extreme Poverty in the United States, 1996-2011.” National Poverty Center Policy Prief #28, February 2012, http://npc.umich.edu/publications/policy_briefs/brief28/policybrief28.pdf

[3] Joshua Leftin, Esa Eslami, and Mark Strayer, “Trends in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation Rates: Fiscal Year 2002 to Fiscal Year 2009,” United States Department of Agriculture Office of Research and Analysis, August 2011, http://www.fns.usda.gov/ORA/menu/Published/SNAP/FILES/Participation/Trends2002-09.pdf

[4] Alisha Coleman-Jensen, Mark Nord, Margaret Andrews, and Steven Carlson, “Household Food Security in the United States in 2010,” Economic Research Service, Report No. (ERR-125) 37 pp, September 2011, http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err125.aspx

[5] This figure uses the official poverty measure, which does not count SNAP as income.

[6] Ruth Rose-Jacobs, et al., “Household Food Insecurity: Associations With At-Risk Infant and Toddler Development.” Pediatrics, Volume 121, Number 1, January 2008, http://www.childrenshealthwatch.org/upload/resource/peds_hh_fi_infantstoddlers_1_08.pdf

[7] John T. Cook and Deborah A. Frank, “Food Security, Poverty, and Human Development in the United States,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Volume 1136, Reducing the Impact of Poverty on Health and Human Development: Scientific Approaches pp. 193–209, June 2008.

[8]J. Cook and K. Jeng, “Child Food Insecurity: The Economic Impact on our Nation,” July 2009, http://www.childrenshealthwatch.org/upload/resource/FA_Report_july2009_full.pdf

[9] “The SNAP Vaccine: Boosting Children’s Health,” Children’s HealthWatch Report, February 2012, http://www.childrenshealthwatch.org/upload/resource/snapvaccine_report_feb12.jpg.pdf; E. March, et al., “Boost to SNAP Benefits Protected Young Children’s Health,” Children’s HealthWatch, October 2011, http://www.childrenshealthwatch.org/upload/resource/snapincrease_brief_oct11.pdf

[10] “Child food insecurity” is the most severe form of food insecurity. Children are often protected from food insecurity as adults in food insecure households reduce their own food intake in order to provide adequate nutrition for children; in households with food insecurity among children, however, the children are subject to reductions and changes in food intake.