Many policymakers and pundits assume that raising federal income taxes on high-income households would have serious adverse consequences for the economy. Yet this belief, which has been subject to extensive research and analysis, does not fare well under scrutiny. As three leading tax economists recently concluded in a comprehensive review of the empirical evidence, “there is no compelling evidence to date of real responses of upper income taxpayers to changes in tax rates.”[1] The literature suggests that if the alternative to raising taxes is larger deficits, then modest tax increases on high-income households would likely be more beneficial for the economy over the long run.

The debate over the economic effects of higher taxes on people with high incomes has focused on a number of issues — how increasing taxes at the top would affect taxable income and revenue as well as the effects on work and labor supply, saving and investment, small businesses, entrepreneurship, and, ultimately, economic growth and jobs. Here is a summary of what the evidence shows.

- Taxable income and revenue. Opponents of raising the taxes that high-income households face often point to findings that high-income taxpayers respond to tax-rate increases by reporting less income to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) as evidence that high marginal tax rates impose significant costs on the economy. However, an importantstudy by tax economists Joel Slemrod and Alan Auerbach found that such reductions in reported income largely reflect timing and other tax avoidance strategies that taxpayers adopt to minimize their taxable income, not changes in real work, savings, and investment behavior. While such strategies entail some economic costs, these costs are relatively modest. Moreover, policymakers can limit high-income taxpayers’ ability to respond to increases in tax rates by engaging in tax avoidance activity — and also enhance the efficiency of the tax code — by broadening the tax base, as discussed below.

- Work and labor supply. The evidence shows that changes in tax rates that fall within the ranges that policymakers are debating have little impact on high-income individuals’ decisions regarding how much to work. As Leonard Burman, former head of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (TPC), recently testified, “Overall, evidence suggests [high-income Americans’] labor supply is insensitive to tax rates.”[2] A marginal rate increase may encourage some taxpayers to work less because the after-tax return to work declines, but some will choose to work more, to maintain a level of after-tax income similar to what they had before the tax increase. The evidence suggests that these two opposing responses largely cancel each other out.

- Saving and investment. Some claim that tax increases on high-income people — in particular, increases in capital gains and dividend tax rates — depress private saving rates and investment. But as Professor Joel Slemrod has written, “there is no evidence that links aggregate economic performance to capital gains tax rates.”[3] Similarly, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) has reported that most economists find that reducing capital gains tax rates would have only a small — and possibly negative — impact on saving and investment.[4] Although tax increases on high-income individuals might reduce their saving, if the revenue generated is devoted to deficit reduction, the resulting increase in public saving is likely to more than offset any reduction in private saving. CRS concludes, “Capital gains tax rate increases appear to increase public saving and may have little or no effect on private saving. Consequently, capital gains tax increases likely have a positive overall impact on national saving and investment.”[5]

- Small business. The evidence does not support the claim that raising top marginal income tax rates has a heavy impact on small business owners: a recent Treasury analysis finds that only 2.5 percent of small business owners fall into the top two income tax brackets and that these owners receive less than one-third of small business income. Moreover, even those small business owners who would be affected by tax increases on high-income households are unlikely to respond by reducing hiring or new investment. As Tax Policy Center co-director William Gale has noted:[6]

[T]he effective tax rate on small business income is likely to be zero or negative, regardless of small changes in the marginal tax rates. This is for three reasons. First, small businesses can expense (immediately deduct in full) the cost of investment. This alone brings the effective tax rate on new investment to zero, regardless of the statutory rate. Second, if they can finance the investment with debt, the interest payments would be tax deductible, making the effective tax rate negative. Third, they can deduct wage payments in full, so the marginal tax rate should have minimal impact on hiring.

In addition, a review of the research finds little evidence for the common assertion that small businesses are responsible for the majority of job creation in the United States or that tax breaks for small businesses generally — as distinguished from start-up ventures — are effective at stimulating jobs or growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

- Entrepreneurship. CRS finds that “An extensive empirical literature on [the relationship between income tax rate increases and business formation] is mixed, but largely suggests that higher tax rates are more likely to encourage, rather than discourage, self-employment.”[7] One reason is that taxes may reduce earnings volatility, with the government bearing some of the risk of a new venture — by allowing tax deductions for losses — and receiving some of the returns. Further, there is little evidence that the current preferential tax rates for capital gains and dividends substantially stimulate investment in new ventures.

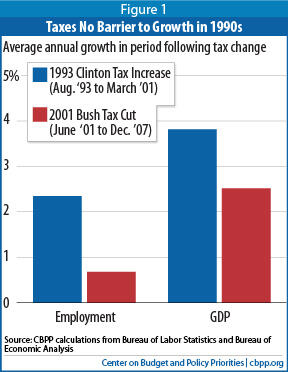

- Growth and jobs. History shows that higher taxes are compatible with economic growth and job creation: job creation and GDP growth were significantly stronger following the Clinton tax increases than following the Bush tax cuts. Further, the Congressional Budget office (CBO) concludes that letting the Bush-era tax cuts expire on schedule would strengthen long-term economic growth, on balance, if policymakers used the revenue saved to reduce deficits. In other words, any negative impact on economic growth from increasing taxes on high-income people would be more than offset by the positive effects of using the resulting revenue gain to reduce the budget deficit. Tax increases can also be used to fund, or to forestall cuts in, productive public investments in areas that support growth such as public education, basic research, and infrastructure.

These findings from the research literature stand in contrast to assertions of extensive economic damage from increases in tax rates on high-income households, which are repeated so often that many policymakers, journalists, and ordinary citizens may simply assume they are solid and well-established. They are not.

These issues are of considerable importance, because sustainable deficit reduction is not likely to be possible without significant revenue increases. Unsupported claims that modest rate increases for high-income people would significantly impair growth ought not stand in the way of balanced deficit-reduction strategies that ask such individuals to share in the burden and pay somewhat more in taxes.

Raising revenues by broadening the tax base can in fact improve the efficiency of the tax code. And, because a cleaner tax code offers fewer opportunities to evade taxes, base broadening can reduce the economic cost of any rates increases also needed to achieve fiscal sustainability.

Studies show that when marginal tax rates increase, high-income taxpayers reduce the amount of taxable income they report and do so to a greater extent than low- and moderate-income taxpayers. Some argue that this fact shows that raising taxes on high-income taxpayers, particularly by increasing statutory tax rates, reduces economic activity and limits significantly the revenue that is generated.[9] However, there is little evidence that tax-rate changes prompt high-income taxpayers to significantly change their work hours, saving and investment behavior, or any other “real” economic activity (see later sections for more detail).[10] And the best estimates are that raising taxes above the current low rates would generate significant revenue.

Auerbach and Slemrod[11] find that the decline in reported taxable income following tax-rate increases largely reflects two factors:

- Timing shifts.Taxpayers change the timing of when they derive income; they accelerate income to avoid tax increases or defer it to take advantage of anticipated future tax cuts.[12] For example, there is evidence that taxpayers rushed to cash in their capital gains at the end of 1986 before capital gains tax rates increased.[13]

- Other types of avoidance and evasion. Taxpayers (especially those with high incomes) use accounting and financial techniques to avoid tax. For example, taxpayers may:

- Structure their spending to take advantage of tax deductions (there is evidence, for example, that taxpayers shifted their debt from personal loans to deductible mortgage debt after the 1986 tax reform eliminated the tax deductibility of the former);

- Arrange to receive their income in tax-preferred entities (for example, the share of businesses structured as S corporations, whose profits are “passed through” to owners for tax purposes, rather than C corporations, whose profits are subject to the corporate income tax, has risen significantly in recent decades[14] );

- Arrange to receive their income in tax-preferred forms(such as capital gains or carried interest, rather than ordinary income); or

- Defer income to postpone tax liability (such as through pensions and other forms of deferred compensation).

Slemrod and Auerbach conclude that timing and other avoidance behaviors are the behaviors most responsive to tax changes, while changes in real productive activities are actually the least responsive. These timing and avoidance behaviors also likely explain why studies find that high-income taxpayers tend to reduce their taxable income more than low-income taxpayers in response to tax increases.[15] High-income taxpayers can engage in these behaviors more easily than other taxpayers, since they tend to generate their income from multiple sources and can afford to hire lawyers and accountants to structure their income so that they owe as little tax as possible.

The fact that much of the measured response of high-income taxpayers to tax increases is due to tax avoidance and timing shifts is important for two reasons. First, it means that much of the modest reduction in high-income taxpayers’ reported taxable incomes in the face of tax increases is occurring on tax returns but not in the real world. There is, to be sure, some change in behavior and resulting economic waste associated with tax avoidance: resources spent on avoiding taxes could otherwise be put to more productive uses. But this is not the same as saying that most or all of the reduction in reported taxable income is because of reductions in work, saving or investment. [16]

Secondly, tax reforms can limit taxpayers’ ability to engage in tax avoidance — such as through measures that broaden the tax base by limiting the use of deductions and tax shelters.[17] This also suggests that while many tax reform proposals would broaden the tax base and dedicate some or all of the resulting revenues to reducing tax rates, base-broadening measures can complement increases in marginal tax rates by substantially reducing the tax-avoidance cost of such increases.[18]

In any event, the best evidence suggests policymakers should not worry that raising taxes on high-income taxpayers will reduce revenues. High-income taxpayers’ response to tax increases is sufficiently modest — and current tax rates are sufficiently low — that there is considerable room for policymakers to collect more revenue by raising federal income tax rates.

In a recent study, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) economist and Nobel Laureate Peter Diamond and economist Emmanuel Saez of the University of California at Berkeley calculated that income tax revenues would not be maximized until the top rate reached 48 percent under the current tax base, or 76 percent if policymakers expanded the tax base to reduce opportunities for tax avoidance.[19] These calculations are based on an upper-bound estimate of how responsive high-income taxpayers are to the top tax rate.[20] Some opponents of tax increases at the top of the income distribution have argued, based on older estimates, that high-income taxpayers are much more responsive. But as the box on page 6 explains, these older estimates are not reliable.[21]

When estimating the revenue gained by raising taxes on high-income groups, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and the Treasury Department take into account the best evidence about how high-income taxpayers reduce their taxable income in response to tax increases.[22] JCT and Treasury find that after taking these responses into account, modest increases in the top marginal tax rates would raise significant revenue.[23] For example:

- Treasury estimates that allowing the cuts in income taxesfor high-income households (those with adjusted gross incomes above $250,000 for married filers and $200,000 for single filers) and estate taxes that were enacted in 2001 and 2003 to expire at the end of 2012 would save a $968 billion over the next ten years.[24]

- Similarly, JCT estimates that imposing surcharges of 2 percent on joint returns with adjusted gross incomes between $350,000 and $500,000, 3 percent on joint returns between $500,000 and $1 million, and 5.4 percent on joint returns above $1 million, starting in 2011, would have raised more than $60 billion a year when fully in effect.[25]

- These figures are exclusive of the additional savings that would result from lower interest payments on the debt or any other macroeconomic responses if policymakers used the revenues for deficit reduction.

In a 1995 paper,a Harvard economist Martin Feldstein wrote that cuts in marginal tax rates in 1986 led to a “dramatic increase in taxable income,” particularly for high-income taxpayers. Feldstein relied on this finding in a Wall Street Journal op-ed arguing that a deficit-reduction package should cut marginal income tax rates rather than raise them.b But more recent literature has pointed out significant flaws in Feldstein’s 1995 paper and others like it:

- As former CBO and Office of Management and Budget director Peter Orszag has noted, Feldstein’s study overlooked the fact that high-income taxpayers’ incomes were rising substantially for other reasons in the period when the 1986 law was passed.c More broadly, the Feldstein study did not control for important ways in which high-income taxpayers differ from other taxpayers, which led it to overstate the amount by which high-income taxpayers’ taxable incomes rose in response to the 1986 marginal rate cuts. Tax scholar Reuven Avi-Yonah has summarized the more recent literature as showing that:d

In fact, the rich are different in at least three ways. First, their incomes have recently been trending upward at a rate that is faster than others’ incomes, which, in a time of tax cuts for the rich, can appear as tax responsiveness. Second, the rich are more sensitive to demand conditions than others, and therefore their incomes tend to surge in good times that also happen to coincide with tax cuts [as was the case with the 1986 Tax Reform Act, which was enacted in a period of strong economic growth]. Finally, the compensation of the rich can easily be moved to a different taxable year, and consequently observed changes in taxable income may reflect timing rather than long-lasting behavioral responses to tax changes.

Former Chairman of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers Austan Goolsbee estimates that the combination of these factors cuts [the estimates of how much high-income taxpayers respond to tax changes] by over 75 percent. Similarly, [economists Roger] Gordon and [Joel] Slemrod suggest that natural experiments around the 1986 Act can be misleading because they reflect shifting of income from corporations (whose rates went up) to individuals (whose rates went down).

- Studies such as Feldstein’s tend to track changes in taxable income over short periodsf and thus cannot ascertain whether a short-term increase in reported income is due to an increase in actual income or to a change in when income is derived and in how much of it is reported.

In addition, the 1986 tax reform law not only cut marginal rates but also broadened the tax base significantly, so the subsequent increase in reported taxable income also reflects the fact that the new tax rules required more complete reporting of income. CRS suggests that insufficiently adjusting for this base broadening may be one reason why a number of studies have shown that changes in taxable income were much greater after the 1986 tax reform than after other tax changes.e

a “The Effect of Marginal Tax Rates on Taxable Income: A Panel Study of the 1986 Tax Reform Act,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 103, No. 3 (Jun., 1995), p. 551.

b “The Tax Reform Evidence From 1986,” Wall Street Journal,October 24, 2011 http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204002304576629481571778262.html.

c Peter R. Orszag, “Marginal Tax Rate Reductions and the Economy: What Would Be the Long-Term Effects of the Bush Tax Cut?,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 16, 2001, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=1701.

d Reuven S. Avi-Yonah “Why Tax the Rich? Efficiency, Equity, and Progressive Taxation,” Yale Law Journal,February 26, 2002, http://www.yalelawjournal.org/pdf/111-6/Avi-YonahFINAL.pdf.

e Austan Goolsbee, “It’s Not About the Money: Why Natural Experiments Don’t Work on the Rich,” in ed. Joel B. Slemrod (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), at p.144.

fIbid, at p.145. See also Jane G. Gravelle, “Revenue Feedback from the 2001-2003 Tax Cuts”, Congressional Research Service, September 27, 2006, Appendix, for a discussion of other problems in similar studies.

Opponents of raising effective marginal income tax rates on high-income taxpayers claim that higher rates would discourage them from working, thereby reducing labor supply and harming the economy.[26] But for high-income taxpayers in particular, as Leonard Burman recently observed, “evidence suggests their labor supply is insensitive to tax rates.”[27]

The empirical evidence on how U.S. taxpayers have responded to tax increases indicates that, at most, high-income taxpayers respond to large cuts in tax rates with negligible increases in work hours.[28] Johns Hopkins economist Robert Moffitt and Purdue and Pennsylvania State University economist Mark Wilhelm report that work hours among working-age men remained essentially unchanged in response to the marginal tax rate changes made by the 1986 tax law.[29] Moffitt and Wilhelm’s finding is consistent with earlier empirical studies: University of Michigan Professor Reuven Avi-Yonah has written that the literature as a whole suggests “high-income men are unlikely to decrease hours worked as tax rates go up.”[30] Other groups, such as married women and older workers have been shown to be very responsive to tax rate changes, but the evidence generally doesn’t show similar responses for those at the top of the income distribution.[31]

The fact that changes in income tax rates have little impact on high-income taxpayers probably reflects a rough balance between the two separate and opposing impacts of an increase in tax rates on taxpayers’ decisions about how many hours to work:

- By reducing the after-tax return per hour worked, a rate increase encourages taxpayers to reduce their work hours because it makes working an additional hour less attractive compared to leisure (this is known as the “substitution effect”).

- But, by reducing taxpayers’ total income for any given number of hours worked, a rate increase may encourage them to increase their work hours, since they need to work more to receive the same amount of after-tax income (this is known as the “income effect”).

The interaction of these offsetting effects determines the net impact on work hours of an increase in marginal tax rates, and the empirical evidence suggests that the impact for high-income taxpayers is quite weak. Or, as Avi-Yonah has pointed out, perhaps the reason for the weak observed response is that neither of these effects matters that much; high-income taxpayers may want to do the work they do irrespective of their specific tax rates or the precise amount of their after-tax income.[32]

In fact, CBO estimates that the top 40 percent of income earners would change their work hours by less than one-fifth as much, in response to a change in tax rates, as would the bottom 10 percent of income earners.[33] That is, while studies show that higher income taxpayers reduce their reported taxable income more in response to tax increases than low- and moderate-income taxpayers, the opposite is thought to be true when it comes to actual hours worked: the evidence suggests that high-earners’ labor supply is less responsive to tax increases, compared to low- and moderate-income taxpayers’.

In sum, the evidence suggests that increasing marginal tax rates for high-income taxpayers does not significantly reduce their labor supply and that the labor supply decisions of high-income taxpayers are, if anything, less sensitive to changes in tax rates than those of low- and moderate-income taxpayers.

There are a number of reasons why Congress should consider modestly raising taxes at the top of the income distribution as part of a balanced deficit-reduction plan.

- Higher-income individuals can afford to share in the sacrifices needed to reduce long-term deficits. An analysis of IRS data by Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez shows that the top 1 percent of households received nearly 20 percent (19.8) of the nation's total adjusted gross income in 2010 (the most recent year available), far more than the entire bottom half of the population had.

- High-income taxpayers have benefited disproportionately from the 2001-2003 tax cuts. In 2011, according to the Tax Policy Center, households earning more than $1 million are receiving an average of $128,832 in tax cuts (equal to a 6.2 percent increase in their average after-tax income), while households earning between $30,000 and $40,000 are receiving an average tax cut of $719 (a 2.4 percent increase in after-tax income).a

- Policymakers can raise significant revenues at the top of the income distribution. When billionaire investor Warren Buffet called on policymakers to “get serious about shared sacrifice” by raising taxes on the nation’s wealthiest individuals, some critics claimed this wouldn’t make a serious dent in our budget problems. But simply allowing the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts for taxpayers with incomes over $250,000 ($200,000 for single filers) to expire would contribute $968 billion to deficit reduction over the next ten years (excluding the savings on interest payments on the debt). Various other methods of increasing effective tax rates at the top of the income distribution also would bring in significant revenue. (Of course, substantial changes also will be needed in the spending side of the budget and elsewhere in the tax code.)

Finally, failure to include, as part of deficit reduction, measures that ask high-income individuals to contribute more in taxes would require low- and middle-income households to bear an overly large share of the deficit reduction burden through steep spending cuts. If shared sacrifice in reaching fiscal sustainability is to be achieved, the only way to include high income households in a significant way is through tax increases. Given the need to reduce deficits, and the need for revenues to make a contribution, it would be odd to suggest that those with the highest incomes should be exempt.

a Tax Policy Center Table T10-0132, “Extend 2001-03 Tax Cuts and AMT Patch; Baseline: Current Law; Distribution by Cash Income Level, 2011”. Estate tax is kept the same as under current law.

Saving and Investment

There is little support for claims that raising income taxes or capital gains taxes on high-income people depresses either national saving or investment. It is important to consider not only how a tax increase will affect private saving rates and the total stock of private savings,[34] but also how the revenues generated are used: if used for deficit reduction, such a tax increase may increase national saving and investment.

Capital gains tax rates primarily affect high-income people since they earn most of the capital gains income. (See box on page 10.) Increases in capital gains rates can decrease the returns to saving, but there is no evidence that this causes private saving rates or national saving and investment to fall.

If a taxpayer has a fixed savings goal, such as a fixed amount to help pay for a child’s college education, increasing marginal tax rates might lead the taxpayer to save more in order to offset the tax increase (the “income effect”).[35] That incentive to save at a higher rate leans against the incentive to save less as a result of the lower after-tax return (the “substitution effect”).

As is the case with labor supply, the empirical evidence is that for capital gains tax changes of the magnitude experienced over recent decades, these two effects roughly balance out. In the words of the Congressional Research Service (CRS), “most empirical evidence does not support a large savings response”[36] to changes in capital gains rates. The CRS also points out that “saving rates have fallen over the past 30 years while the capital gains tax rate has fallen from 28% in 1987 to 15% today (0% for taxpayers in the 10% and 15% tax brackets) . . . [which] suggests that changing capital gains tax rates have had little effect on private saving.”[37] CRS concludes that, on the whole:

Many economists note that capital gains tax reductions appear to have little or even a negative effect on saving and investment. . . . Consequently, capital gains tax rate reductions are unlikely to have much effect on the long-term level of output or the path to the long-run level of output (i.e., economic growth).

The theory and evidence thus matches Warren Buffet’s observation:[38]

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, tax rates for the rich were far higher, and my percentage [tax] rate was in the middle of the pack. According to a theory I sometimes hear, I should have thrown a fit and refused to invest because of the elevated tax rates on capital gains and dividends. I didn’t refuse, nor did others. I have worked with investors for 60 years and I have yet to see anyone — not even when capital gains rates were 39.9 percent in 1976-77 — shy away from a sensible investment because of the tax rate on the potential gain. People invest to make money, and potential taxes have never scared them off.

CRS also reports that reducing capital gains tax rates could have some negative effects on private saving and investment. One reason is that the capital gains tax can “act as insurance for risky investments by reducing losses as well as gains — it decreases the variability of returns.” This is because, while taxes are levied on capital gains, taxpayers can claim tax deductions for capital losses.[39] CRS notes that “the capital gains tax, therefore, may have little effect on risk-taking and may even encourage it.”[40]

Not only is there no evidence that raising capital gains taxes reduces private saving, but because the revenues generated may be used to reduce deficits, the overall impact of a capital gains tax increase may be to increase national saving and investment. As the CRS notes, “Capital gains tax rate increases appear to increase public saving and may have little or no effect on private saving.

Consequently, capital gains tax increases likely have a positive overall impact on national saving and investment.”[41]

Furthermore, a large differential between the tax rates on capital gains and the tax rates on other types of income fuels tax avoidance. It diverts capital to relatively unproductive investments that taxpayers would not invest in but for the tax benefit. It also encourages elaborate schemes to convert ordinary income into capital gains to achieve the tax benefit. Thus, to the extent that raising capital gains tax rates reduces the differential and discourages such tax sheltering behavior, doing so may increase economic efficiency. That is former Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center Director Leonard Burman’s point in his comment on the 2003 capital gains tax cut,

“shelter investments are invariably lousy, unproductive ventures that would never exist but for tax benefits. And money poured down these sinkholes isn’t available for more productive activities. What’s more, the creative energy devoted to cooking up tax shelters could otherwise be channeled into something productive… Bottom line: low rates for capital gains are as likely to depress the economy as to stimulate it.”[42]

Looking for a link between capital gains tax rates and growth more directly, Joel Slemrod found, “there is no evidence that links aggregate economic performance to capital gains tax rates.”[43] In addition, the Tax Policy Center has reported that capital gains taxes have little apparent effect on stock market growth and that, “Arguments that the maximum [capital gains] tax rate affects economic growth are even more tenuous”; it finds no statistically significant correlation between capital gains rates and real GDP growth during the last 50 years.[44]

While this paper focuses primarily on the issue of raising effective income tax rates at the top of the income distribution, policymakers should also consider increases in the capital gains and dividend rates. These preferential rates are much lower than normal marginal income tax rates, and their benefits go overwhelmingly to high-income individuals.

The Joint Committee on Taxation classifies the preferential rates on capital gains and long-term dividends as a tax expenditure and estimates that together they will cost $457 billion in forgone revenues over 2011-2015, compared to taxing capital gains and dividends at the normal individual marginal tax rates.a

The benefits of the preferential rates on capital gains and dividends are highly regressive. TPC estimates that in 2007, more than 83 percent of the benefits from these preferential rates went to the top 1 percent of households, which received an average of $46,000 annually (5.1 percent of their after-tax income) from this tax break. Less than 2 percent of the benefits went to the bottom 80 percent of households.b

Some argue that reducing or eliminating the tax preference for capital gains would harm growth. As this paper explains, the evidence does not support claims that capital gains tax rates significantly affect saving rates, stock market growth, investment, or economic growth.

a This “static” estimate does not account for likely behavioral changes (e.g., in timing of realizations) that would result from taxing capital gains as ordinary income. Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2010-2014,” December 15, 2010, and assumes current law http://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=3718.

b “Tax Capital Gains as Ordinary Income, Distribution of Federal Tax Change,” Tax Policy Center distribution tables T08-0052 http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/displayatab.cfm?Docid=1763&DocTypeID=2 and T08-0051 http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/displayatab.cfm?Docid=1762&DocTypeID=1.

A tax increase on a high-income taxpayer reduces how much disposable income they have to save and consume. And, because an income tax reduces returns to saving, it may also affect the private saving rate. Like a capital gains tax increase, an income tax increase will have both income and substitution effects: it will encourage taxpayers to save at a higher rate to offset the tax increase, but also encourage them to save at a lower rate (i.e., consume more of their income immediately) by reducing the after-tax return to saving. The aggregate effect of such a tax increase on private savings rates and wealth (the private savings stock) depends on the interaction of these various effects.

There is little empirical data on how a tax increase focused solely on high-income taxpayers affects their saving, and in particular, on the long-run effects of such a tax increase in an economy that is operating at capacity. (For a discussion of how tax increases and cuts might affect growth in an economy that is in recession, see the box on p 12.)

However, what matters for economic growth and the future standard of living is the impact of increasing marginal income tax rates on national saving (the sum of public and private saving). If the revenues generated are used to reduce deficits, which represent public “dissaving,” then the increase in public saving will more than offset the decrease in private saving, and overall national saving — and the pool of capital available for investment — will rise.

Harvard economist Robert Barro has argued that such an increase in national saving would not materialize because, when households see that government saving is increasing (or government dissaving is falling), they will reduce their own saving in expectation of lower taxes in the future. [45] But the overwhelming empirical evidence is that any such reduction in private saving would, at most, only partially offset the increase in government saving.[46]

The fact that deficit-financed tax cuts reduce national saving and thus act as a drag on future economic growth is the key reason why CBO projects that, over the longer term, extending the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts without paying for them would likely reduce economic growth and national income.[47]

The claim that raising marginal tax rates at the top of the income distribution would severely harm small businesses has little empirical basis. Few small business owners pay taxes at the top rates. According to a recent Treasury analysis, only 2.5 percent of small business owners who are taxed at the individual rather than corporate rates are in the top two income-tax brackets.[48]

Further, claims that about half of “pass-through” business income (i.e., income that firms pass through to their owners, who pay income taxes on these profits) is taxed at the top two tax rates[49] are also misleading. These claims rely on an extremely broad definition of “business” that treats any filer with any business income as a business owner. Under that definition, professors who occasionally get paid for giving a speech or doing some consulting on the side, lawyers and accountants whose firms are organized as partnerships, and corporate executives who get paid to sit on other firms’ boards of directors are treated as small business owners. A recent Treasury

When the economy is operating at less than full capacity — that is, when actual GDP falls short of potential GDP — policies that boost aggregate demand for goods and services can help to close that output gap and reduce the economic costs and human hardship of an economic slump.

The most effective policies to boost aggregate demand, per dollar of budget cost, in a weak economy are those that deliver extra resources to those who are most likely to spend immediately (rather than save) a large share of whatever they receive. The business or person receiving any money spent may also spend some portion of what they receive, further boosting demand, and so on (the “multiplier” effect).

High-income taxpayers tend to save a much greater proportion of the last dollar of income they receive than low- and moderate-income households do.a This is why CBO estimates that tax cuts for lower-income people generate much more near-term output per dollar of budget cost — i.e., have a greater multiplier effect — than tax cuts directed at high-income people.b

Such multiplier effects — by which either spending increases or tax cuts boost aggregate demand and actual GDP — are absent when the economy is producing at capacity. Under those circumstances, increases in government spending or tax cuts that would boost aggregate demand would tend to translate into higher prices rather than increased GDP, because the economy would not have the capacity to meet the increase in demand. Monetary policymakers would increase interest rates to head off inflation, and interest-sensitive spending like housing, business investment, and net exports would fall by enough to accommodate the increased government purchases and private consumption.

Thus, in the long run, it makes more sense to consider how a tax cut directed at high-income people might alter labor supply, saving rates, entrepreneurship, and other types of economic activity that could increase growth by lifting potential GDP. As this paper shows however, there is little evidence that such tax cuts do in fact significantly alter those types of economic activity or increase potential GDP. And, to the extent that such tax cuts increase long-run deficits, they will tend to slow economic growth.

a Dynan, Skinner, and Zeldes find evidence that over a lifetime, people with higher lifetime incomes have higher average savings rates. Karen E. Dynan, Jonathan Skinner, and Stephen P. Zeldes, “Do the rich save more?,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2000-52, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.), 2000.

b Spending increases, once the money is actually dispersed, in general tend to have higher multipliers than tax cuts, because for every dollar of budgetary cost, at least one dollar of a spending increase flows directly into new spending (and increased aggregate demand), whereas some portion of every dollar spent on a tax cut may be saved. For a more complete discussion, see Chad Stone, testimony before the Senate Budget Committee, September 15, 2011, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3582.

Department analysis instead defines a small business as one with at least $5,000 of deductions on activities that are considered “businesslike” and with income and deductions of less than $10 million; it defines a small business owner as an individual who derives at least 25 percent of his or her adjusted gross income from a small business. Under these more reasonable parameters, the percentage of small business income earned by filers who face the top two tax rates falls to 26 percent.

In addition, as noted above, Tax Policy Center co-director William Gale has written that “the effective tax rate on small business income is likely to be zero or negative, regardless of small changes in the marginal tax rates,” because of the valuable array of tax subsidies that small businesses receive.[50] As CRS explains, the subsidies with the broadest reach include “the taxation of small firms as pass-through entities, the graduated rate structure for the corporate income tax, the expensing allowance for equipment …, the exemption of some small corporations from the corporate alternative minimum tax, cash basis accounting, and the exclusion from taxation of capital gains on the sale or disposition of certain small business stock.”[51]

Given these facts, the imagined impact on small businesses is a weak justification for extending the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts for the highest earners, which would increase the deficit by more than $1 trillion (including additional interest payments) over the next ten years, or for shielding very high-income individuals from making a significant contribution to deficit reduction.

Policymakers have channeled a large volume of tax breaks to small businesses, primarily on the assumptions that small businesses are the primary creators of jobs and that tax policy strongly affects small business job creation. Yet both assumptions are shaky. The claim that small businesses are the primary creator of jobs is based on research conducted in the 1980s; as CRS notes, “more recent research has revealed some methodological deficiencies in these original studies and suggests that small businesses contribute only slightly more jobs than other firms relative to their employment share. Moreover, this differential is not due to hiring by existing small firms, but rather to startups, which tend to be small.”[52]

Similarly, a 2010 study by Haltiwanger, Jarmin, and Miranda finds no systematic relationship between firm size and job growth after controlling for firms’ age.[53] This indicates that it is particularly important to distinguish between young startup businesses, which the study finds “contribute substantially to both gross and net job creation” (as well as to gross job destruction when they fail, as many startups do), and other small businesses, which on average generate no more net job growth than do larger businesses.[54]

The evidence that tax rates strongly affect small business growth and job creation is also thin. Only one study exists that directly addresses the question of whether cutting the marginal tax rates of small business owners leads to increased hiring in existing firms. That study, by Douglas Holtz-Eakin and others, finds a statistically significant increase in small business hiring following the deep cuts in tax rates from the 1986 tax reform.[55] But CRS notes that the study may overstate the extent to which high-income entrepreneurs respond to tax changes, in part because it does not adequately control for the ways that high-income taxpayers’ behavior is likely to differ from that of other taxpayers. (See the box discussing a 1995 Feldstein study, page 6.) CRS also cautions that “given only one study, it is premature to conclude that raising taxes of the owner would decrease hiring in existing firms.”[56]

Opponents of raising the top marginal income tax rates on capital gains and dividends argue that doing so would discourage entrepreneurship and new small business ventures.[57] Yet CRS reported that “the empirical evidence suggests that tax rates have small, uncertain, and possibly unexpected effects on the formation of small business.” Summarizing the economic literature, CRS concludes that “higher tax rates are more likely to encourage, rather than discourage, self-employment.”[58]

One potential reason for this unexpected finding is that taxes may encourage risk-taking and entrepreneurship by reducing business losses as well as gains and thus acting like a form of “insurance for risky investment.”[59] CRS has explained that “earnings tend to vary more among the self-employed, and higher tax rates reduce the variance of earnings.” That is, federal taxes may in effect cause the government to function as a partner in the business venture “bearing some of the risk and receiving some of the return.”[60]

It has also been argued that raising tax rates on capital gains would discourage high-income taxpayers fromcreating and investing in new firms. A CRS study finds little support for this claim either:[61]

- Much of the formal venture capital to new firms comes from venture capital institutions, many of which are already exempt from the capital gains tax and thus would be unaffected by an increase in the capital gains rate. Many such institutions, for example are nonprofits that apply their capital gains to tax-exempt purposes or foreign institutions not subject to U.S. income tax.

- Some gains in the value of new stock that certain small corporations issue are exempt from the capital gains tax. Thus, raising capital gains taxes could actually encourage investment in new firms by widening the tax advantage that such investments have over investments in existing ventures.

- While some argue that a capital gains tax increase would impede new ventures from using stock options to attract skilled executives, the types of stock options that firms commonly offer executives are not subject to capital gains tax.

As this analysis has shown, the empirical literature provides little evidence that high-income taxpayers significantly change their economic behavior in response to changes in effective marginal income tax rates in the ranges being discussed. This lack of evidence undercuts claims that relatively modest marginal income tax rate increases will have a large, negative impact on the economy. A simple look at the historical record reinforces that conclusion.

The tax rates in effect during the Clinton administration coincided with strong economic growth. As Figure 1 shows, job creation and economic growth were significantly stronger in the recovery following the marginal income tax increases enacted in 1993 than they were following the 2001 Bush tax cuts. Further, small businesses generated jobs at twice the rate during the Clinton years than they did under the Bush tax code.

This does not prove that the Clinton Administration tax rates caused employment and GDP growth or that such growth would not have been stronger without those tax rates in place. That would require controlling for the many factors that affect job and economic growth. There is good reason to think, however, that higher tax rates can indeed contribute to growth if policymakers use the resulting revenues in ways that support growth. The Clinton Administration tax rates and revenues allowed budget deficits to be lowered, increasing national saving and reducing the long-term costs of borrowing, and this may have enabled the private sector to increase investment in ways that improved growth.

Furthermore, CBO has concluded that if Congress extends the Bush tax cuts indefinitely without paying for them, the large increases in deficits that would result would likely create a net

drag on national saving and economic growth.

[64] William Gale and Peter Orszag similarly concluded that the Bush tax cuts are “likely to reduce, not increase, national income in the long term” because of their effect in swelling the deficit.

[65] As Leonard Burman has testified:

[66] The Congressional Budget Office, Joint Committee on Taxation, and the Treasury all conducted studies in the early 2000s. They concluded that tax rate cuts could boost the economy in the short-run, but not by nearly enough to offset the direct revenue loss. The long-run effect depended on how the deficits were closed...In all cases, the effects were small.”

Policymakers also can use a portion of revenues for other growth-enhancing purposes, such as investing in education to improve the productivity of the workforce and in infrastructure to support business and trade activity. The point is, as Professor Joel Slemrod has written,[67]

Clearly, taxes affect behavior; they affect some behaviors more than others. What has not been established is that the level of taxes has a clear and important impact on economic growth. And one reason is that this is not a well-posed question. How government activity affects prosperity depends not only on the level of taxes, but also on what the money is used for.

The nation faces a daunting fiscal challenge, as well as historically large income inequality and increased spending needs stemming from the graying of the population and advances in medicine that improve health but add to cost.[68] These challenges mean that revenues, as well as spending cuts, need to make a significant contribution to deficit reduction.

Policymakers can raise revenues in several ways. Reducing inefficient “tax expenditures” — targeted tax preferences that are akin to spending programs but are delivered through the tax code — can raise needed revenue and also make the tax code more economically efficient. Tax expenditures cost more than $1 trillion a year, more than Medicare and Medicaid combined.[69] The Bowles-Simpson report, the Rivlin-Domenici task force, and the Senate Gang of Six all identified tax expenditure reform as a significant source of deficit reduction.

Any serious attempt at broadening the tax base by reforming tax expenditures would affect high-income taxpayers. About 70 percent of individual tax expenditures are provided through tax deductions, exemptions, or exclusions, the value of which rises with income. As a result, the most affluent households often receive the largest tax subsidies even though they generally are the people leastlikely to need a tax incentive to undertake the activity the incentive is designed to promote, such as saving for retirement, buying a home, or sending a child to college. This structure reduces both the efficiency and the fairness of many of these tax incentives. Some tax expenditures also decrease the efficiency of the tax code by encouraging taxpayers to engage in various tax avoidance strategies in order to take advantage of the tax breaks.

Because base broadening can increase the efficiency of the tax code, it generally is sound tax policy to aim for as broad a base and low a rate as possible to raise a given amount of revenue. But this does not mean that marginal rate increases for high-income taxpayers should be off the table as a source of revenues — much less that the revenues gained from base broadening should be used to pay for cuts in marginal rates, as in some recent proposals. (See Appendix for a brief technical discussion.) Rather, base broadening should be considered alongside tax rate increases as a revenue-raising option, for the following reasons:

- The nation’s revenue needs are significant, and many tax expenditures either meet important needs or are politically difficult to change in ways that would yield substantial revenues. Two of the most costly tax expenditures, for example, are politically popular: the mortgage interest deduction and the exclusion from adjusted gross income of employer-sponsored health insurance. A sign of the political difficulty of cutting tax expenditures deeply is the recent proposals to “broaden the base and lower the rates” from Senator Pat Toomey, former governor Mitt Romney, and House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan, which specify tax rate cuts but do not identify a single tax expenditure they would cut.

- As discussed above, studies have found that the incomes of high-income taxpayers decline only modestly in response to taxes and that much of that response reflects timing shifts and other tax avoidance. Tax avoidance carries some economic cost, but likely not as much as if high-income taxpayers responded to taxes by working and saving less. Moreover, whatever base broadening policymakers can achieve would reduce the economic cost of raising income tax rates by reducing opportunities for tax avoidance.

- The economic cost of unsustainable government debt is much higher than the cost of modestly raising tax rates. As noted above, CBO has concluded that allowing the Bush tax cuts to expire would support economic growth by raising national savings.[70] Tax increases also can be used to fund, or to forestall cuts in, productive public investments in areas that support growth, such as education, infrastructure, and basic scientific research.

- If rate increases are off the table, low- and moderate-income taxpayers are likely to bear an even greater share of the burden of deficit reduction than they would otherwise, through even deeper budget cuts in programs targeted on them or through cuts in tax expenditures from which they benefit.

A good start to raising needed revenues would be to allow the income, capital gains and dividends, and estate-tax rate cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 for high-income households to expire as scheduled in 2013. The Obama Administration has proposed allowing these tax cuts to expire for taxpayers with incomes over $250,000 (over $200,000 for single filers), saving more than $1 trillion over the next ten years, including debt service savings.

The research in the field does not provide strong evidence that modestly raising tax rates at the top of the income scale would have significant growth-reducing effects on labor supply, taxable income, savings and investment, or entrepreneurship. Moreover, as Professor Joel Slemrod has emphasized, the economic impact of tax increases depends in part on how the revenue raised is used.[71] In the current fiscal and political environment, policymakers would likely use revenue raised by increasing marginal tax rates for high-income taxpayers to reduce deficits, which likely would have positive overall effects on long-term economic growth.

Broadening the tax base by reducing targeted tax preferences that tend to disproportionately benefit high-income taxpayers can improve the efficiency of the tax code. And, because a cleaner tax code offers fewer opportunities to evade taxes, base broadening also can reduce economic waste associated with increases in tax rates. For this reason, base-broadening measures can complement modest rate increases in a way that allows policymakers to raise revenues without impeding economic growth.

Including such revenue-raising measures in a larger deficit-reduction effort would also facilitate enactment of a large package that also includes sizeable expenditure reductions. It would represent a more balanced approach to deficit reduction than the alternative of shielding higher-income Americans from tax increases and thereby requiring low- and middle-income Americans to shoulder most of the load. Fairness, as well as growth, matters for tax policy.

The rule of thumb that policymakers should aim for as broad a tax base and low a rate as possible to raise a given amount of revenue reflects the fact that the economic costs associated with higher tax rates (“deadweight losses”) are approximately proportional to the square of the tax rate. However, as tax economist Professor John Creedy emphasizes, policymakers must also consider evidence about the absolute size of the economic cost of the rate increases under consideration (which may be modest), as well as other concerns, such as fairness.[72]

To try to measure the economic cost of raising taxes, some recent studies have used “elasticity of taxable income” (ETI), which measures in ratio form the percentage change in taxable income resulting from a 1 percent change in the share of an individual’s income that he or she retains after taxes (this share is known as the “net of tax rate”). An increase in the tax rate reduces the net of tax rate and leads to behavioral responses that reduce taxable income (either through reduced efforts to earn income or tax avoidance behavior). The higher the taxable income elasticity, the greater the response of taxable income to a tax increase, and the higher the economic cost of raising taxes.

Some of the early empirical studies of the ETI produced very high estimates, above 1.0 in some cases. The box on page 6 explains that these early estimates employed flawed methods that likely overstated significantly the true responsiveness of taxpayers to taxes. A 2002 study by Gruber and Saez attempted to address many of these methodological shortcomings, such as by attempting to control for the fact that high-income taxpayers’ incomes may grow at faster rates than other taxpayers’ incomes; it found an ETI for high-income taxpayers of 0.57.[73] Moreover, a recent study by Diamond and Saez considers that figure an “upper bound estimate of the distortion of top U.S. tax rates,”[74] and as Peter Orszag has explained, the figure may substantially overstate the responsiveness of taxable income to tax rate increases.[75] Further, to the extent that the ETI captures avoidance responses, it may overstate the economic costs of raising tax rates: while avoidance has an economic cost of its own, it may be more modest than if the entire ETI were explained by “real” changes to work, savings, and other economic behavior.[76]