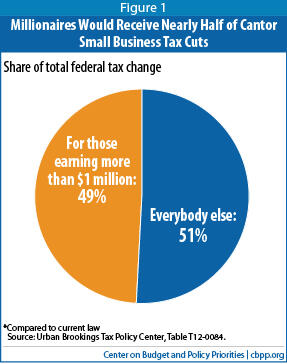

Though billed as a measure to create jobs by aiding small businesses, House Majority Leader Eric Cantor's (R-VA) proposal for a 20 percent tax deduction in 2012 for businesses with fewer than 500 employees would benefit many high-income taxpayers — including many affluent doctors, lawyers, and stockbrokers — while failing to generate the promised economic benefits.[1] The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center estimates that nearly half — 49 percent — of the $46 billion tax cut that the measure would provide would go to people with incomes over $1 million a year.[2]

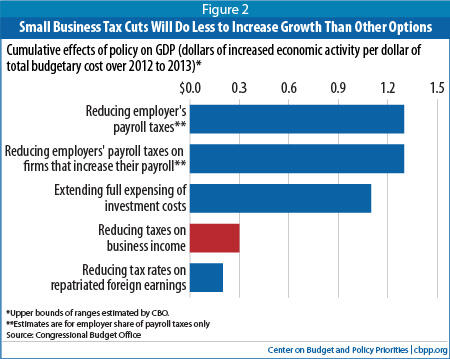

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) rated this general approach as one of the least cost-effective ways that policymakers were considering to encourage growth or create jobs in a weak economy. For one thing, the tax benefits would flow disproportionately to high-income people who would spend a relatively small share of their additional income; thus, CBO estimated that the deduction would generate just 0 to 20 cents of additional economic activity in 2012 for every dollar in budgetary cost. For another, firms would receive this tax break whether they hired new workers or not; thus, CBO estimated that in 2012 it would create one job or fewer per $1 million of budgetary cost.

The Cantor proposal is even more troubling than his earlier version of it in 2010. Whereas the earlier version did not provide tax breaks for high-paying businesses that one would not ordinarily view as "small businesses" — such as stock brokerage firms and professional sports teams — the new proposal contains no such exclusion and lets these firms, as well, enjoy lucrative tax cuts.

The Cantor proposal also ignores the emerging consensus among economists that young small firms, not small ones in general, are particularly important "job creators." As a recent study concluded, "policies targeting firms based on size without taking account of the role [of] firm age are unlikely to have the desired impact on job creation."[3]

The Cantor proposal would provide a 20 percent deduction for various types of business income for firms with fewer than 500 employees, including income flowing from partnerships, S Corporations, and C Corporations.

[4] To qualify for the deduction, the income must be "active." That is, to qualify for the tax break, a taxpayer must not merely invest in the firm but also materially participate in its operation during the year. The deduction would be limited to 50 percent of certain wages paid. The Joint Tax Committee estimates that the proposal, which would be in effect for 2012, would cost $46 billion.

[5] The Tax Policy Center analysis shows how the benefits of this tax cut would be apportioned:

- Some 49 percent of the tax cut would go to the 0.3 percent of people with incomes exceeding $1 million in 2012; they each would receive an average tax cut of more than $44,000.

- The wealthiest four percent of taxpayers — those with incomes above $200,000 — would receive 84 percent of the tax cut.

- Only 16 percent of the tax cut would go to the 96 percent of Americans making less than $200,000.

Last year, CBO analyzed 13 policy options for their impact on economic growth and job creation in 2012 and 2013 (i.e., in a weak economy) per million dollars of budgetary cost[6] — including the approach that is reflected in the Cantor proposal. It concluded that the option to "allow all types of businesses to deduct a percentage of their net income in calculating their tax liability" ranked next to last. (The only less cost-effective option was a repatriation tax holiday for foreign profits.)

CBO noted that the benefits of deducting a percentage of business income would flow disproportionately to high-income people, who would spend a relatively small share of this additional income. CBO concluded, therefore, that this option would generate just 0 to 20 cents of additional Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for each dollar of budgetary cost in 2012 and just zero to 30 cents in GDP per dollar of cost through 2013.[7]

CBO also estimated that the resulting job creation would be paltry, at zero to one job in 2012 per $1 million of budgetary cost, and zero to three jobs in 2012-2013.[8] This is not surprising, given the option's lack of any tie to job creation. A wealthy, active partner in a business would receive a big tax cut regardless of whether the business hires an additional person.

CBO highlighted much more efficient ways to boost growth and jobs in a weak economy, including an Administration proposal to cut payroll taxes for small business that hire additional workers. The Administration later proposed a different small business tax credit that also is contingent on job creation. Both proposals would deliver more "bang for the buck" than the Cantor proposal because, as CBO noted, policies such as a payroll tax cut for small businesses that hire additional people "would provide tax benefits linked to payroll growth; fewer budget dollars would be used to cut taxes for workers who would have been employed anyway, so the incentive to increase payroll per dollar of forgone revenues would be greater."[9]

Majority Leader Cantor justified his proposal by arguing that small businesses create a disproportionate number of jobs. That's a common but erroneous assumption: a well regarded and widely circulated recent analysis shows that young businesses, not small ones, create a disproportionate share of jobs. The authors concluded:[10]

- The "main finding is that once we control for firm age there is no systematic relationship between firm size and growth."

- "Our findings show that small, mature businesses have negative net job creation and economic theory suggests this is not where job growth is likely to come from."

- "Our findings highlight the important role of business startups and young businesses in U.S. job creation. Business startups contribute substantially to both gross and net job creation."

- "Our findings suggest that policies targeting firms based on size without taking account of the role [of] firm age are unlikely to have the desired impact on job creation."

Their conclusion represents an emerging consensus among economists. As the Congressional Budget Office wrote earlier this year:

Small firms employ a substantial share of all workers and are among the most dynamic employers in the economy. That very dynamism, however, leads small firms to both create and eliminate jobs at higher rates than larger firms do, in part because small firms come in to and go out of existence at much higher rates than their larger counterparts — a pattern that persisted through the most recent recession. Although small firms do generate jobs at higher rates, on net, than larger firms do, that relationship arises primarily because new firms, which typically start out small, create a comparatively large share of net new jobs. Conversely, older, more established small firms create a comparatively small share of net new jobs. Thus, even though observers sometimes cite small firms as the engine of job growth, the more accurate view is that new firms are a particularly important source of job growth. [11]

To fully understand why the Cantor proposal would not add significantly to job creation, one also needs to understand the typical characteristics of job-creating young firms.[12] Young firms, even successful ones, typically lose money in their early years. Firms can "carry forward" these losses, termed "net operating losses," into future years to offset part or all of their profits in those years. This means that while wealthy lawyers, doctors, and stockbrokers would benefit from this proposed tax deduction, typical job-creating young firms would not.