- Home

- Chairman Ryan Gets 62 Percent Of His Hug...

Chairman Ryan Gets 62 Percent of His Huge Budget Cuts from Programs for Lower-Income Americans

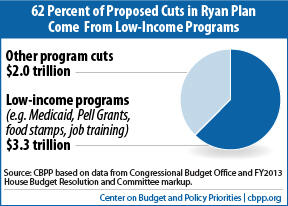

House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan’s budget plan would get at least 62 percent of its $5.3 trillion in nondefense budget cuts over ten years (relative to a continuation of current policies) from programs that serve people of limited means. This stands a core principle of President Obama’s fiscal commission on its head and violates basic principles of fairness.

Not much has changed on this front from Chairman Ryan’s fiscal year 2012 budget plan released a year ago. Then, too, Chairman Ryan proposed massive spending cuts, the bulk of which were in programs that serve low- and moderate-income Americans. (Compared with last year’s plan, the cuts in low-income programs are larger in dollar terms but slightly smaller as a shareof the total cuts; see box.)

The plan of Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson, who co-chaired President Obama’s National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, established, as a basic principle, that deficit reduction should not increase poverty or widen inequality. The Ryan plan charts a different course, turning its biggest cannons on low- and moderate-income people.

Chairman Ryan’s budget proposes $5.3 trillion in nondefense budget cuts (and about $200 billion in defense increases). The $5.3 trillion in cuts includes $1.2 trillion in cuts to nondefense discretionary programs; this $1.2 trillion in cuts is beyond the cuts needed to comply with the strict funding caps that the Budget Control Act established. Several hundred billion dollars of these additional cuts would very likely come from low-income programs.

Comparing This Year’s Ryan Budget to Last Year’s

In last year’s Ryan budget, the cuts over ten years (fiscal years 2012-2021) totaled $4.5 trillion, of which at least $2.9 trillion — about 65 percent — would come from low-income programs. In Chairman Ryan’s new budget, the cuts (exclusive of the proposed defense spending increases) total $5.3 trillion over ten years (fiscal years 2013-2022), of which at least $3.3 trillion — 62 percent — would come from low-income programs.

In other words, the size of the low-income cuts is a bit larger, while their percentage of the total cuts is a bit smaller because the cuts as a whole are bigger.

This comparison, however, understates the degree to which both the total budget cuts and the low-income cuts have grown from last year’s Ryan budget to this year’s. The cuts in this year’s budget are measured relative to a baseline that already reflects large cuts in discretionary programs as a result of the enactment of discretionary funding caps in last August’s Budget Control Act. Chairman Ryan’s $5.3 trillion in new cuts would be on top of those reductions.

Total cuts in low-income programs (including cuts in both discretionary and entitlement programs) appear likely to account for at least $3.3 trillion — or 62 percent — of Chairman Ryan’s total budget cuts, and probably significantly more than that; as explained below, our assumptions regarding the size of the low-income cuts are conservative. The $3.3 trillion includes the following four categories of cuts:

- $2.4 trillion in reductions from Medicaid and other health care for people with low or moderate incomes. The plan shows Medicaid cuts of $810 billion, plus savings of $1.6 trillion from repealing the health reform law’s Medicaid expansion and its subsidies to help low- and moderate-income people purchase health insurance.

- $134 billion in cuts to SNAP, formerly known as the Food Stamp Program. If Chairman Ryan’s proposed SNAP savings were achieved entirely through eligibility cuts, between 8 and 10 million people would be knocked off the program.[1]

- At least $463 billion in cuts in mandatory programs serving low-income Americans (other than Medicaid and SNAP). Chairman Ryan’s budget documents indicate that he is proposing $1.2 trillion in cuts in mandatory programs other than Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and other health programs, but the documents do not specify how much specific programs would be cut (with the exception of SNAP[2]). For this analysis, we make the conservative assumption that savings from low-income mandatory programs (other than Medicaid and SNAP) would be proportionate to their share of spending in this category. Thus, we derive the $463 billion figure from the fact that 45 percent of mandatory spending other than for Social Security, health care, and SNAP goes for programs for low- and moderate-income individuals and families.

This likely substantially understates the cuts that the plan would make in low-income programs. The Ryan documents show that $758 billion in cuts would come from mandatory programs just in the income security portion of the budget (function 600), and the bulk of the mandatory spending in that category goes for low-income programs. The documents also show $166 billion in mandatory cuts in the education, training, employment, and social services portion of the budget (function 500), which, based on the discussion in the Ryan budget documents, would likely come mainly from the mandatory portion of the Pell Grant program for low-income students. - At least $291 billion in cuts in low-income discretionary programs. Bear in mind that these cuts are on top of the cuts already enacted as a result of the discretionary caps created by the Budget Control Act. The Ryan budget documents released on March 20 show the plan contains $1.2 trillion in cuts in nondefense discretionary programs beyond the cuts needed to comply with the caps, but do not provide details about the cuts to specific programs. (The documents do identify some major low-income programs, including the discretionary part of Pell Grants and job training programs, as prime targets for cuts.) Here, too, we make the conservative assumption that low-income programs in this category would bear only a proportionate share of the cuts. Thus, we derive the $291 billion figure from the fact that about a quarter of nondefense discretionary spending goes for programs for low- and moderate-income individuals and families.

As noted, our estimates of the size of the cuts in low-income programs — which assume these programs will merely bear a proportionate share of the budget cuts required in each of the relevant budget categories — are conservative. When faced with the choice of which specific programs to cut, policymakers are not likely to cut much from a number of the non-low-income programs in these budget categories that are popular, such as veterans’ disability compensation, veterans’ health, the FBI, and cancer research. That means that other programs — including low-income programs — would have to be cut by more than their proportionate share.

Appendix

In this analysis, we examine entitlement and discretionary programs other than for defense and war — i.e., nondefense funding. (This approach also excludes net interest payments.) The Ryan budget increases defense spending above the caps that the Budget Control Act has established by about $200 billion over the next ten years, reducing its $5.3 trillion total in gross nondefense spending cuts to a net $5.1 trillion in overall program cuts.

We compare Chairman Ryan’s budget proposal to a current policy baseline. We adjust CBO’s March 2012 baseline, which assumes that all provisions of current law take effect as scheduled, to reflect the continuation of current spending policies:

- We assume that sequestration, triggered by the failure of the Joint Select Committee to propose a comprehensive deficit reduction plan, does not take effect. While sequestration from 2013-2021 is current law, it is not scheduled to take effect until January 2013 and we do not consider it to be current policy. We remove the effects of the sequestration from the CBO baseline using CBO’s estimate of its effects.

- We assume extension of almost all expiring tax cuts. These tax cuts include certain refundable tax credits, whose refundable portions are officially treated as spending rather than as lost revenues. (We do not assume extension of the temporary payroll-tax reduction.)

- We assume extension of relief from the scheduled steep reduction in physician reimbursement rates under Medicare’s sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula, through a freeze on current rates.

These all are standard assumptions that most budget analysts make in producing a current policy baseline, and CBO provides estimates for each of these alternatives to current law. These assumptions are identical to the non-defense spending assumptions used by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget in its current policy baseline and by CBO in its “Alternative Fiscal Scenario.”

End Notes

[1] Dottie Rosenbaum, Ryan Budget Would Slash SNAP Funding by $134 Billion Over Ten Years: Low-Income Households in All States Would Feel Sharp Effects, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 21, 2012, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3717.

[2] The exact SNAP cuts were revealed during the House Budget Committee markup of the House budget resolution; Chairman Ryan’s staff also suggested cuts in farm programs and federal employee retirement but provided no dollar figures. See James Horney, “The Massive Hidden Safety-Net Cuts in Chairman Ryan’s Budget,” Off the Charts blog, March 21, 2012, http://www.offthechartsblog.org/the-massive-hidden-safety-net-cuts-in-chairman-ryans-budget/.