- Home

- Romney Budget Proposals Would Necessitat...

Romney Budget Proposals Would Necessitate Very Large Cuts in Medicaid, Education, Health Research and Other Programs

Governor Mitt Romney’s proposals to cap total federal spending at 20 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) and boost defense spending to 4 percent of GDP would require very large cuts in other programs, both entitlements and discretionary programs.

This update of an earlier analysis is based on updated economic and budget projections that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) issued this summer and additional information that the Romney campaign has provided on his budget proposals. The resulting estimates of the required budget cuts are somewhat smaller than the ones we released on May 21, but they are still very deep.

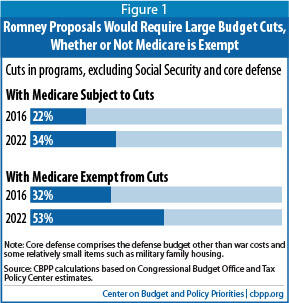

For the most part, Governor Romney has not outlined cuts in specific programs. But if policymakers repealed health reform (the Affordable Care Act, or ACA) and exempted Social Security from cuts, as Romney has suggested, and cut Medicare, Medicaid, and all other entitlement and discretionary programs by the same percentage to meet Romney’s overall spending cap and defense spending target, then they would have to cut non-defense programs other than Social Security by 22 percent in 2016 and 34 percent in 2022 (see Figure 1). If they exempted Medicare from cuts for this period, the cuts in other programs would have to be even more dramatic — 32 percent in 2016 and 53 percent in 2022.

If they applied these cuts proportionately, the cuts in programs such as veterans’ disability compensation, Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for poor elderly and disabled individuals, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps), school lunches and other child nutrition programs, and unemployment compensation would cause the incomes of large numbers of households to fall below the poverty line. Many who already are poor would become poorer.

These cuts would be noticeably deeper than those required under the austere House-passed budget plan authored by Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-WI). (Romney’s nondefense cuts are deeper because his proposal increases core defense spending — the defense budget other than war costs and some relatively small items such as military family housing — to 4 percent of GDP, while the Ryan budget does not.) Over the coming decade, Romney would require cuts in programs other than core defense of $6.1 trillion, compared with $5.0 trillion in cuts under the House-passed budget plan.

The Romney Budget Proposals

During his campaign, Governor Romney has made three proposals that would significantly affect the composition and overall level of federal spending:

- Cap total spending: “Reduce federal spending to 20 percent of GDP by the end of my first term” and “cap it at that level.”[1]

- Increase defense spending: “[Set] core defense spending — meaning funds devoted to the fundamental military components of personnel, operations and maintenance, procurement, and research and development — at a floor of 4 percent of GDP.”[2] These categories encompass 93 percent of the national defense budget function.

- Repeal the Affordable Care Act: “Work with Congress to repeal the full legislation as quickly as possible.”[3]

This paper examines the combined effect of these proposals to determine the amount of spending that would be available for programs other than core defense. Setting core defense spending at 4 percent of GDP would leave 16 percent of GDP for all other federal programs, including Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, and interest payments on the debt.

To evaluate the proposals, we also must make assumptions about a few additional elements that Governor Romney has not specified. He has stated that he will limit spending to 20 percent of GDP “by the end of my first term,” by which he apparently means 2016. We also assume that the 4 percent of GDP target for core defense spending would be effective by 2016. (See the appendix for further details about our methodology.)

Governor Romney has promised to put the federal government “on a path to a balanced budget.”[4] But, he has recently indicated that “it could take longer than two presidential terms to get the job done, as he had previously hoped.”[5] Since Romney’s balanced-budget proposal is not fully specified, we have not factored it into these estimates. Had we done so, the required budget cuts would be even deeper than those reported here — the level of tax revenue under the Romney proposals would be less than 20 percent of GDP, so balancing the budget would require cutting federal expenditures below the 20 percent level.

Governor Romney has also said that he will permanently extend certain tax cuts that are scheduled to expire, cut taxes further, and offset part or all of the additional tax cuts by reducing or eliminating unspecified tax preferences. Although recent analysis by the Tax Policy Center raises questions about whether reductions in tax preferences could fully offset the cost of the additional tax cuts,[6] the net cost of the tax cuts makes little difference to this analysis, since it doesn’t assume the budget will be balanced in the coming decade.

How Deep Would the Budget Cuts Have to Be?

Governor Romney’s budget proposals would require cuts of $588 billion in 2016 alone and $6.1 trillion over the 2014-2022 period in programs outside of core defense. These cuts are measured relative to our projection of current budget policy, using CBO’s latest estimates, which include the BCA’s discretionary caps (but not the across-the-board spending cuts, or sequestration, currently scheduled to take effect in January 2013 due to the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction’s failure to reach an agreement). The cuts we show in this analysis come on top of those needed to adhere to the caps.

- Repealing health reform would reduce spending by nearly $900 billion over the 2014-2022 period. That would leave other cuts of $487 billion in 2016 and $5.2 trillion over the decade that Romney largely does not specify.

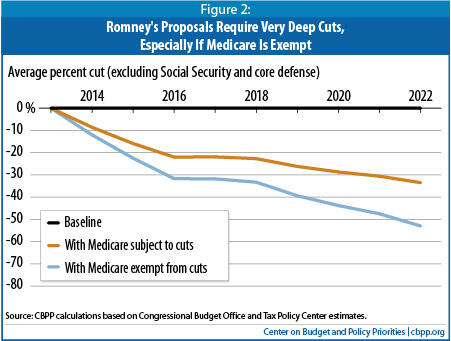

The required percentage cuts in affected programs would grow deeper with each passing year (see Figure 2). If policymakers spread the cuts needed (after health reform’s repeal) proportionately across all programs other than core defense and Social Security, they would have to cut all other programs — including Medicare and Medicaid — by 22 percent in 2016 and 34 percent in 2022.

- If policymakers spared Medicare from cuts over the coming decade and spread the required cuts proportionately across all programs other than core defense, Social Security, and Medicare, they would have to cut all other programs by 32 percent in 2016 and 53 percent in 2022 — that is, by about one-third and one-half, respectively.

- To the extent that policymakers also spared other programs from these cuts — for example, veterans’ benefits, military and civilian service retirement, the FBI, or air traffic control — the cuts in all remaining programs would have to be still deeper.

The Romney campaign says that holding spending to 20 percent of GDP “requires spending cuts of approximately $500 billion per year in 2016 assuming robust economic recovery with 4% annual growth.”[7] In comparison, we estimate that Governor Romney’s 20-percent cap would require $588 billion in cuts in 2016 (assuming 4 percent of GDP is reserved for core defense). Our cuts are measured from a current policy baseline that reflects CBO’s most up-to-date economic and budget projections, issued in August, which assume that real economic growth will average about 3 percent a year over the next four years. This difference in assumptions about economic growth likely explains much or all of the difference in these estimates.

What Might These Cuts Mean for Specific Programs?

Table 1 shows the cuts that the Romney proposals could require in selected programs, both with Medicare subject to cuts and with Medicare exempt.

- If Medicare is subject to cuts, that program would be cut by a net of $95 billion in 2016 and $1.0 trillion from 2014 through 2022. These amounts reflect the increase in Medicare costs that would come from repealing health reform, offset by the even larger cuts needed to hit the spending cap. Achieving cuts of this size solely by reducing payments to hospitals, physicians, and other health care providers could jeopardize beneficiaries’ access to care. As a result, beneficiaries would very likely face substantial increases in premiums and cost-sharing charges.

- Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) would face cumulative cuts of $1.5 trillion through 2022 if Medicare is subject to cuts and $1.9 trillion if Medicare is exempt. Repealing health reform’s coverage expansions, as Governor Romney has proposed, would reduce Medicaid spending by $618 billion over the next ten years and account for 30 to 40 percent of the reductions. Repealing health reform by itself would leave uninsured 30 million people who would have gained coverage under health reform, according to CBO.[8] Analysis by the Urban Institute suggests that the additional Medicaid cuts would likely add at least 14 million to 19 million more people to the ranks of the uninsured.[9]

- Reducing SNAP by those percentages would cause 10 to 14 million fewer low-income people to be assisted in 2016, SNAP benefits to be reduced by $1,300 to $1,800 a year for a family of four, or some combination of the two. (The reductions depend on whether Medicare is subject to cuts or is exempted.) These cuts would primarily affect poor families with children, elderly individuals, and people with disabilities.

- Compensation payments for disabled veterans (which average less than $13,000 a year) would be cut by one-fifth to one-third, as would pensions for low-income veterans (which average about $11,000 a year) and SSI benefits for poor aged and disabled individuals (which average about $6,000 a year and leave poor elderly and disabled people well below the poverty line).

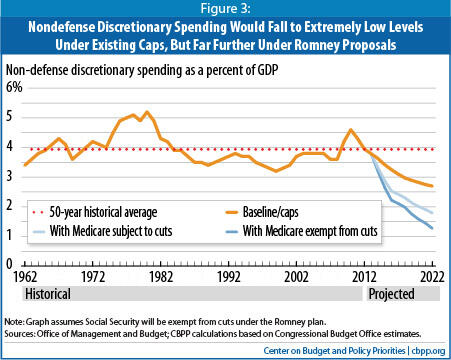

- Nondefense discretionary spending would be cut by $133 billion in 2016 — and $1.3 trillion through 2022 — if Medicare is subject to cuts. These cuts would come on top of the cuts already reflected in the budget baseline as a result of the BCA’s caps. This category of spending covers a wide variety of public services such as aid to elementary and secondary education, veterans’ health care, law enforcement, highways and mass transit, national parks, environmental protection, biomedical and scientific research, housing assistance, the weather service, and air traffic controllers.

- Nondefense discretionary spending would shrink to 1.8 percent of GDP by 2022 if Medicare is subject to cuts, and to 1.3 percent of GDP if Medicare is exempt. (See Figure 3.) In contrast, spending for this category has averaged 3.9 percent of GDP over the past 50 years and has never fallen below 3.2 percent of GDP during this period.

| Table 1 Entitlement and Discretionary Program Cuts Required by Romney Proposals In billions of dollars | ||||||

| With Medicare Subject to Cuts | With Medicare Exempt from Cuts | |||||

| In 2016 | In 2022 | 2014-2022 | In 2016 | In 2022 | 2014-2022 | |

| Percentage cut in all programs except Social Security and core defense | 22.0% | 33.5% | 31.7% | 53.0% | ||

| Total required program cuts | 588 | 1,098 | 6,124 | 588 | 1,098 | 6,124 |

| Cuts to Selected Programs (if all programs except Social Security and core defense are cut by the same percentage) | ||||||

| Medicare (net cut or increase) a/ | 95 | 230 | 1,034 | 52 increase | 130 increase | 713 increase |

| Medicaid (total cut) a/ | 133 | 264 | 1,472 | 165 | 362 | 1,904 |

| Health insurance subsidies and related spending a/ | 93 | 152 | 984 | 93 | 152 | 984 |

| SSI, SNAP, child nutrition, and refundable parts of CTC and EITC | 53 | 83 | 501 | 76 | 132 | 750 |

| Federal retirement | 37 | 70 | 386 | 54 | 111 | 579 |

| Veterans' disability compensation and other entitlement benefits for veterans | 18 | 33 | 179 | 26 | 51 | 268 |

| Total Non-defense discretionary [resulting level as a percent of GDP] | 133 [2.5%] | 224 [1.8%] | 1,326 | 191 [2.2%] | 354 [1.3%] | 1,988 |

| a.Includes effect of repealing the Affordable Care Act. If the ACA is repealed and Medicare is exempt from cuts, Medicare spending will increase above the budget baseline due to the repeal of the ACA provisions that produce Medicare savings. Notes: Program cuts are relative to a baseline that reflects the caps in the Budget Control Act (BCA). Program cuts do not include associated interest savings. Cuts beyond repeal of health reform are assumed to be distributed equally across the board except to Social Security, core defense, and (in the right-hand columns) Medicare. Core defense comprises the defense budget other than war costs and some relatively small items such as military family housing. | ||||||

A Closer Look at Health Programs

This analysis assumes that, under Governor Romney’s budget proposals, policymakers repeal health reform and impose budget cuts proportionally to achieve the needed additional spending reductions. We model two scenarios, in one of which policymakers protect Medicare from the proportional cuts. Table 2 shows how these provisions interact.

Under Governor Romney’s plan, Medicaid would be cut twice: first, by repealing health reform’s Medicaid expansion and, second, by subjecting the program to further proportional cuts. Protecting Medicare from cuts would come, in part, at Medicaid’s expense. Medicaid would be cut by a total of 44 percent in 2022 if Medicare is subject to reductions and by 61 percent if Medicare is exempted.

| Table 2 Effect of Romney Proposals on Major Health Programs In billions of dollars | |||||

| With Medicare Subject to Cuts | With Medicare Exempt from Cuts | ||||

| In 2022 | 2014-2022 | In 2022 | 2014-2022 | ||

| Medicare | |||||

| Effect of repealing ACA | + 14% | + 713 | + 14% | + 713 | |

| Additional proportional cut | - 34% | - 1,747 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total change | - 24% | - 1,034 | + 14% | + 713 | |

| Medicaid | |||||

| Effect of repealing ACA | - 16% | - 618 | - 16% | - 618 | |

| Additional proportional cut | - 34% | - 854 | - 53% | - 1,287 | |

| Total change | - 44% | - 1,472 | - 61% | - 1,904 | |

| Health Insurance Subsidies and Related Spending | |||||

| Effect of repealing ACA | -100% | - 984 | - 100% | - 984 | |

Romney Proposals Would Require Even Deeper Cuts than House-Passed Budget

Governor Romney’s budget proposals would entail spending significantly more for defense than the House-passed budget resolution and less on other programs. The House plan, authored by Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-WI), itself includes steep cuts in entitlement and discretionary programs outside of national defense.

- Under the House plan, core defense spending would total about $5.7 trillion over the ten-year period 2013-2022.[10] The Romney plan would increase core defense spending to $7.8 trillion. The House plan would increase core defense funding modestly relative to the existing BCA caps, but core defense would nevertheless decline as a share of the economy to 2.6 percent of GDP by 2022. In contrast, Governor Romney would increase core defense to 4.0 percent of GDP.

- The House plan would cut entitlement and discretionary programs (outside of core defense and net interest) by $5.0 trillion over ten years.[11] The Romney proposal would cut this spending by $6.1 trillion. Thus, Governor Romney’s ten-year cuts would be about 20 percent deeper than those in the House budget plan.

Appendix

Methods and Assumptions

Approach. The analysis in this paper starts from CBO’s August 2012 current-law baseline budget projections and adjusts those figures to reflect current budget policy, as explained below.[12] We calculate spending levels by assuming that policymakers limit the size of the total budget to 20 percent of GDP by 2016 while reserving 4 percent of GDP for core defense; this leaves 16 percent of GDP for all other spending. The needed cuts represent the difference between the baseline level of spending for programs outside core defense and interest and this 16-percent cap.

Baseline assumptions. We adjust CBO’s August baseline, which is based on scheduled requirements under current law, to reflect the continuation of all expiring tax cuts (both middle-class and upper-income), including relief from the alternative minimum tax through indexing, estate tax relief under current parameters, and the normal “tax extenders.” This produces what analysts call a “current policy baseline;” most budget plans now being discussed, and most discussions of how to put a budget plan together, now use a current policy baseline.

Our estimates do not assume continuation of the temporary payroll-tax reduction. The estimates assume extension of the refundable portions of tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC), which affects baseline spending since tax refunds that exceed income tax liability are recorded as spending in the federal budget.

These current-policy assumptions increase deficits relative to current law and therefore increase debt and interest on the debt. Interest payments are included within Governor Romney’s 16 percent-of-GDP cap.

In addition, we assume that the number of troops engaged in Afghanistan is reduced to 45,000 by 2015, in accordance with CBO’s scenario estimating the budgetary effects of phasing down U.S. operations there. We also assume that relief from the scheduled steep reduction in physician reimbursement rates under Medicare’s sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula is continued by freezing current payment rates. These all are standard assumptions that most budget analysts make in producing a “current policy” baseline, and CBO provides estimates for each of these alternative policies, including the associated changes in interest costs.[13] CBO itself makes all these adjustments when producing its “alternative fiscal scenario,” other than the assumption of a troop drawdown.

CBO’s August baseline assumes adherence to the discretionary caps put in place by the Budget Control Act of 2011, which imposes separate caps on defense and nondefense discretionary funding for all years from 2013 through 2021. Our figures therefore start with the resulting, separate defense and nondefense discretionary funding levels. We do not assume that the sequestration scheduled to occur over the 2013-2021 period will occur; we remove the effects of the sequestration from the CBO baseline using CBO’s estimate of its effects, and we use CBO’s interest rate assumptions to calculate the resulting change in interest costs.

Calculation of spending cuts. In the final step, we calculate the size of the program cuts that are required, taking into account the resulting interest savings, to meet the 16-percent-of-GDP target. We assume that core defense spending will increase in equal steps between 2014 and 2016 until it reaches 4 percent of GDP. Governor Romney has defined “core” defense as covering four types of defense accounts: military personnel; operations and maintenance; procurement; and research, development, testing, and evaluation. Because these defense accounts constitute 93 percent of total non-war funding in the national defense function, our baseline for core defense spending is estimated at 93 percent of the outlays for national defense contained in the CBO baseline that shows the funding levels for these programs under the BCA caps before sequestration.

We assume that Social Security will not be cut within the ten-year budget window, since Governor Romney said in a debate on January 17, “First of all, for the people who are already retired or 55 years of age or older, nothing changes.”[14]

We assume that outlay savings in all other spending programs start in 2014 and grow in equal steps between then and 2016 as necessary to hit the cap on non-core defense spending of 16 percent of GDP in that year. After 2016, core defense remains at 4 percent of GDP and the cuts in other programs except Social Security grow only as needed to maintain the 16-percent-of-GDP target. We calculate the interest payments consistent with the overall spending and revenue totals.

The dollar cuts of $6.1 trillion over ten years that we report in this analysis apply to the rest of the budget — that is, to all entitlement and discretionary programs excluding Social Security, core defense, and net interest. However, to calculate the unspecified cuts, we first assume that health reform is repealed. Doing so increases Medicare spending but reduces spending for Medicaid and for subsidies to individuals buying insurance through the health insurance exchanges being established under the act, as well as risk-adjustment payments for insurance plans operating through the exchanges and other miscellaneous costs. Overall, repeal of health reform reduces total federal spending by almost $900 billion through 2022 (repeal slightly increases deficits during this period but reduces federal spending), and therefore shrinks the size of the required but unspecified cuts to $5.2 trillion. It is this $5.2 trillion that we apply across the board to all programs other than Social Security and core defense in our analysis and that leads to the percentage cuts we display in the report.

In our alternative scenario, the $5.2 trillion in required, unspecified cuts is applied to all programs other than core defense, Social Security, and Medicare. Of necessity, the percentage and dollar cuts to the remaining programs are deeper than if Medicare is also subject to reductions.

End Notes

[1] Mitt Romney, Remarks on fiscal policy at the Americans for Prosperity “Defending the American Dream Summit,” November 4, 2011, http://thepage.time.com/2011/11/04/transcript-mitt-romney-delivers-remarks-on-fiscal-policy.

[2] Romney for President, National Defense: An American Century, http://www.mittromney.com/issues/national-defense. Accessed September 14, 2012.

[3] Romney for President, Health Care: Repeal and Replace Obamacare, http://www.mittromney.com/issues/health-care. Accessed September 14, 2012.

[4] Mitt Romney, Remarks on fiscal policy at the Americans for Prosperity “Defending the American Dream Summit,” November 4, 2011, http://thepage.time.com/2011/11/04/transcript-mitt-romney-delivers-remarks-on-fiscal-policy/.

[5] Kasie Hunt, “Romney amends budget goals, assails Obama’s record,” Associated Press, June 13, 2012, http://bigstory.ap.org/article/romney-amends-budget-goals-assails-obamas-record.

[6] Hang Nguyen, James Nunns, Eric Toder, and Robertson Williams, “How Hard is it to Cut Tax Preferences to Pay for Lower Tax Rates?” Tax Policy Center, July 10, 2012, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/url.cfm?ID=412608.

[7] Romney for President, Spending: Smaller, Simpler, Smarter Government, http://www.mittromney.com/issues/spending. Accessed September 14, 2012.

[8] Congressional Budget Office, Letter to the Honorable John Boehner, July 24, 2012, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/43471-hr6079.pdf.

[9] John Holahan and others, House Republican Budget Plan: State-by-State Impact of Changes in Medicaid Financing, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, May 2011, http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/8185.pdf. The authors estimate that under Medicaid proposals like those in the House-passed budget, which would reduce federal Medicaid spending by $810 billion over the next ten years, 14 to 27 million people would lose Medicaid coverage.

[10] The House plan does not separate core defense, as Governor Romney defines that term, from other defense activities. But it does specify amounts for the total national defense function. See Committee on the Budget, U.S. House of Representatives, Report to Accompany H. Con. Res. 112, March 23, 2012. Core defense, as Governor Romney defines it, includes military personnel; operations and maintenance; procurement; and research, development, testing and evaluation. The budget accounts covering these parts of the defense budget constitute 93 percent of non-war defense funding. Based on this information, we estimate the amount that the Ryan budget would spend on core defense, excluding war costs.

[11] Based on Committee on the Budget, U.S. House of Representatives, Report to Accompany H. Con. Res. 112. The figures cited represent total outlays for all budget functions other than national defense and net interest, plus an estimate for defense needs outside of “core defense,” as explained in the previous footnote.

[12] Congressional Budget Office, An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2012 to 2022, August 2012, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/08-22-2012-Update_to_Outlook.pdf.

[13] Ibid., Table 1-5.

[14] Transcript, Fox News Channel and Wall Street Journal Debate in South Carolina, January 17, 2012, http://foxnewsinsider.com/2012/01/17/transcript-fox-news-channel-wall-street-journal-debate-in-south-carolina/.