- Home

- State Budget Cuts In The New Fiscal Year...

State Budget Cuts in the New Fiscal Year Are Unnecessarily Harmful

Cuts Are Hitting Hard at Education, Health Care, and State Economies

The cumulative effect of four consecutive years of lagging revenues has led to budget-cutting of historic proportions. An analysis of newly enacted state budgets shows that budget cuts will hit education, health care, and other state-funded services harder in the 2012 fiscal year – which started July 1, 2011 – than in any year since the recession began.

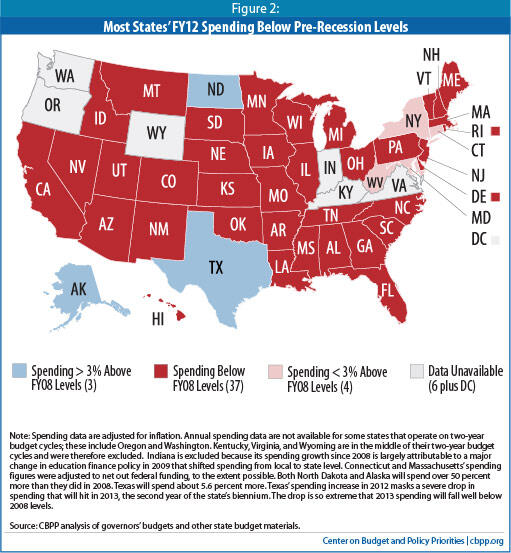

Of the 47 states with newly enacted budgets, 38 or more states are making deep, identifiable cuts in K-12 education, higher education, health care, or other key areas in their budgets for fiscal year 2012. Even as states face rising numbers of children enrolled in public schools, students enrolled in universities, and seniors eligible for services, the vast majority of states (37 of 44 states for which data are available) plan to spend less on services in 2012 than they spent in 2008 – in some cases, much less.

These cuts will slow the nation’s economic recovery and undermine efforts to create jobs over the next year.

This level of budget-cutting is unnecessary and results, in part, from state and federal actions and failures to act. To be sure, with tax collections in most states still well below pre-recession levels and lagging far behind the growing cost of maintaining services, additional cuts at some level were inevitable for 2012. But the cutbacks in services that many states are now imposing are larger than necessary. Many states enacting deep cuts have failed to utilize other important tools in their budget-balancing toolkit, such as tapping reserves or raising new revenue to replace some of the revenue lost to the recession. Some states have even added to the cutbacks by further depleting revenue through tax reductions — an ineffective strategy for improving economic growth that likely will do more harm than good.

Increased federal aid, which played an essential role in limiting the depth of cuts in services like education and health care in recent years, has almost entirely expired. Combined with states’ reluctance to utilize reserves or make tax changes, the loss of this federal aid leaves states with fewer options, one of which is deeper spending cuts. Moreover, Congressional leaders have indicated that they plan to cut back funding to the states for a variety of programs and services — a situation that would lead to further budget-balancing actions at the state level.

A total of 47 states have enacted or are on the verge of enacting budgets for the 2012 fiscal year.[1] A review of these budgets, which in most states took effect July 1, shows that:

- Nearly all states are spending less money than they spent in 2008 (after inflation), even though the cost of providing services will be higher. Most state spending goes toward education and health care, and in the 2012 budget year, there will be more children in public schools, more students enrolled in public colleges and universities, and more Medicaid enrollees in 2012 than there were in 2008. But among 44 states which have released the necessary data, 37 states will spend less in 2012, after inflation, than they did in 2008, and two — Alaska and North Dakota — expect to spend significantly more. (A third state, Texas, is also on track to spend significantly more in 2012 than in 2008, but the two-year budget Texas just enacted calls for very deep cuts in 2013 that would bring spending below 2008 levels.) Total proposed spending would be 8 percent below 2008 inflation-adjusted levels.[2]

- The majority of states — at least 38 of 47 states with new budgets — are making major cuts to core public services. [3]

- At least 23 states have enacted identifiable, deep cuts in pre-kindergarten and/or K-12 spending. Mississippi will fail for the fourth year in a row to meet statutory spending requirements enacted to ensure adequate funding in all school districts. (The three previous years of underfunding have cost over 2,000 school employees their jobs.) Washington’s budget cuts an amount equal to $1,100 per student in K-12 funds for reducing class size, extended learning time, and teachers’ professional development.

- At least 20 states have made identifiable, deep cuts in health care. Arizona has frozen enrollment in part of its Medicaid program, so that an estimated 100,000 low-income people who previously would have qualified will not be able to enter the program, and another 150,000 will face more stringent rules for retaining eligibility. Washington has frozen enrollment for a state-run health plan serving approximately 40,000 low-income residents, which is expected to reduce the number of participants to 37,000 in 2012 and to 33,000 in 2013.

- At least 25 states are making major, identifiable cuts in higher education. Florida’s cuts in funding for the state’s universities has led to tuition hikes of 15 percent for the new school year, bringing the cumulative tuition increase since 2009 to 52 percent. Arizona cut state support for public universities by nearly one-quarter; when combined with previous cuts, this reduces per-student state funding 50 percent below pre-recession levels. California’s new budget reduces funding for the state’s two university systems by more than $1 billion. For one of those two systems, the University of California system, tuition for the 2011-12 school year will be 18 percent above last year’s rates and over 80 percent higher than it was in the 2007-08 school year.

- At least 16 states have proposed layoffs or identifiable cuts in pay and/or benefits for public workers.

- Five states have balanced deep spending cuts with significant revenue-raising measures. These measures include extending expiring tax surcharges, repealing tax credits or deductions, broadening the base of some taxes, and raising rates. For example:

- Connecticut’s budget increased income tax rates for many filers, expanded the sales tax base to include more services, increased the sales tax rate, and instituted a rule that would make it harder for corporations to avoid income taxes, among other revenue measures.

- Hawaii raised over $600 million in new tax revenue over the biennium by limiting general excise tax exemptions for businesses and by eliminating the standard deduction and capping itemized deductions for higher income filers, among other actions.

- Nevada’s budget extended $620 million in tax measures that were scheduled to expire this year.

- By contrast, 12 states with shortfalls enacted large tax cuts; the loss of revenue in 2012 from these tax cuts deepened the spending cuts these states imposed to balance their budgets. In a number of cases, the primary beneficiaries of the tax cuts or expiring tax measures were large corporations and/or high-income individuals. For example:

- Michigan eliminated the state’s major business tax and replaced it with a flat 6 percent corporate income tax, at a cost of more than $1 billion in 2012 alone. To partially offset the revenue lost, the state will maintain and then phase down a temporary increase in the personal income tax, reduce the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit for low-income working families by 70 percent, and tax some pension income. The net result of these tax changes is a revenue loss of $535 million for fiscal year 2012.

- North Carolina enacted a set of tax breaks for businesses that will cost $132 million in fiscal year 2012 and more than $300 million when in full effect.

- In Wisconsin, lawmakers enacted over $90 million in new tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy. Together with other tax cuts enacted earlier this year, the total revenue loss to the state is about $200 million over the next two year budget cycle, requiring further budget cuts. Lawmakers filled $56 million of the budget shortfall by scaling back the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit for 152,000 low-income working families.

- In addition to the 12 states enacting new tax cuts, a number of states – including some of those mentioned above and other states, such as California and Maryland – are allowing temporary tax increases to expire, thereby giving individuals and corporations reductions in their tax liability at a time when families and communities are facing large budget cuts.

- Seven states with budget shortfalls had large reserves available that they could tap to reduce the need for deep spending cuts – but only two did so. In Nebraska, lawmakers used reserve funds in fiscal year 2012 and fiscal year 2013 to reduce the size of the spending cuts they imposed. By protecting the state’s education system and human services from even deeper cuts, this prudent use of reserves is supporting the economic recovery in the near-term, and helping to protect the state’s future economic potential. Iowa also used some reserves. The remaining five states with large reserves and budget shortfalls, however, enacted all-cuts budgets that – somewhat mystifyingly – left their reserves untouched.

Among other effects, the budget cuts are slowing the pace of economic recovery. Cutting state services not only harms vulnerable residents but also slows the economy’s recovery from recession by reducing overall economic activity. When states cut spending, they lay off employees, cancel contracts with vendors, reduce payments to businesses and nonprofits that provide services, and cut benefit payments to individuals. All of these steps remove demand from the economy.

State and local governments already have eliminated 577,000 jobs since August 2008, federal data show, and state budget cuts have cost an unknown but probably very large number of additional jobs in the private sector. These job losses shrink the purchasing power of workers’ families, which in turn affects local businesses and slows recovery. While it is not possible to calculate directly the additional loss of jobs resulting from these newly enacted budget cuts, it appears very likely that the public sector will continue to cut jobs and also to cut funding for some private-sector jobs, negating some of the job growth that otherwise would occur in the economy as a whole.

Moreover, many of the services being cut are important to states’ long-term economic strength. Research shows that in order to prosper, businesses require a well-educated, healthy workforce. Many of the state budget cuts described here will weaken that workforce in the future by diminishing the quality of elementary and high schools, making college less affordable, and reducing residents’ access to health care. In the long term, the savings from today’s cuts may cost states much more in diminished economic growth.

Why States Faced Shortfalls in 2012

States faced record shortfalls in fiscal year 2012 because the recession has continued to hamper state tax collections, the cost of providing services is rising, and emergency federal aid has largely been depleted.

- Revenues remain depressed. The severe recession caused state revenues to decline sharply, and revenues remain depressed going into the 2012 fiscal year, making it difficult for states to maintain public services. Of the 44 states that have released the necessary data, 36 project that they will have less state revenue in 2012 (after adjusting for inflation) than they did in fiscal year 2008, when the recession began. These states on average balanced their budgets based on fiscal year 2012 revenue projections that were 7 percent lower than before the recession, after adjusting for inflation. [4] While state revenues are starting to improve across the country, the rate of growth is generally slow.

- Costs are rising. The cost of meeting people’s needs has increased since the recession began, due both to demographic changes and to the recession. In the upcoming 2011-12 school year, the U.S. Department of Education projects that there will be about 260,000 more K-12 students and another 1.5 million more public college and university students than in 2007-08, for example.[5] Some 5.6 million more people are projected to be eligible for subsidized health insurance through Medicaid in 2012 than were enrolled in 2008, as employers have cancelled their coverage and people have lost jobs and wages.[6]

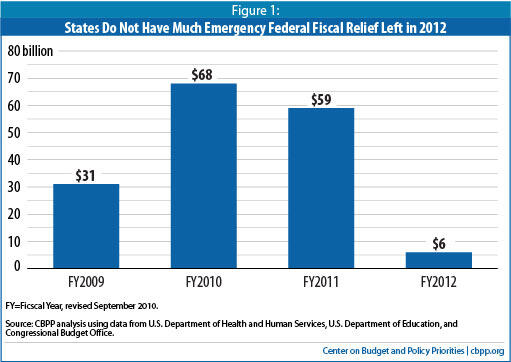

- Emergency federal aid has now ended. States used emergency fiscal relief from the federal government to cover about one-third of their budget shortfalls through the just-completed 2011 fiscal year. Only about $6 billion in fiscal relief remains for fiscal year 2012, a year in which shortfalls total at least $103 billion (see Figure 1). That is, the remaining fiscal relief covers less than 6 percent of state budget shortfalls for the fiscal year that just began.

Not only is emergency federal aid ending, but federal policymakers are considering budget cuts that would significantly reduce the amount of ongoing federal funding to states. About one-third of the category of the federal budget known as “non-security discretionary” spending flows through state governments in the form of funding for education, health care, human services, law enforcement, infrastructure, and other areas. On several occasions this year, Congress has considered very large, immediate cuts in this category of spending. For instance, the House of Representatives proposed cutting it by $66 billion or 14 percent for the current federal fiscal year, which ends in September 2011. [7] Were the federal government to enact a cut of a comparable magnitude for the upcoming fiscal year – as is entirely possible, given the insistence of many members of Congress on deep and immediate cuts – it would reduce federal support for services provided through state and local governments, forcing states to make still-deeper cuts in their budgets.Image

If Congress and the Administration cut non-security spending significantly, the detailed decisions will be made in 10 different appropriations bills later this year. In principle, the appropriations process could spare aid to states while taking all the required cuts from purely federal areas of spending, such as the National Institutes for Health and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. A more likely scenario, however, is that cuts will be deeper to aid to states than to federally administered programs.

States Are Closing Shortfalls with Service Cuts, New Taxes, or Reserves

To meet their balanced budget requirements, states must close their budget shortfalls, as they have in the last three years and in previous recessions. The question for states is how to accomplish this while doing the least damage to the economy, vulnerable residents, and necessary public services. States’ main choices are to draw on reserves, raise taxes, cut spending, or use a combination of these approaches.

- States are enacting major spending cuts. In the three years since the recession began, states already have imposed cuts in all major areas of state services, including health care, services to the elderly and disabled, and K-12 and higher education.[8]

At least 38 of the 47 states that enacted 2012 budgets plan major cuts in services in the 2012 fiscal year, on top of cuts already implemented in all those states in fiscal years 2009, 2010 and/or 2011. In more than four-fifths of the 44 states for which the necessary data are available, states will spend less next year than before the recession hit, after adjusting for inflation (see Figure 2.) On average, those 37 states will spend 8 percent less than their states spent before the recession, adjusted for inflation. (These cuts are detailed starting on p. 10 below.) - A few states left large “rainy day” funds untouched. States entered the recession with the highest reserves on record, including rainy day funds and other general fund balances. Over the last three years, most states have drained their rainy day funds in order to limit the recession’s damage. However, a handful of states held onto substantial reserve funds they have drawn on to avoid some cuts to public services. Specifically, seven states that faced shortfalls for fiscal year 2012 entered their budget deliberations this past spring with rainy day funds equaling more than5 percent of fiscal year 2011 spending (see Table 1).

Only two of those seven states — Nebraska and Iowa — used some of their rainy day funds to help close the state’s shortfall for the new fiscal year. Nebraska has gradually drawn down these funds over the past few years; the newly enacted budget draws down $105 million over the two-year budget period. This would leave $299 million in the fund at the end of fiscal year 2013. Iowa also drew down some of its reserves ($39 million) for fiscal year 2012, leaving about $400 million untouched.

In contrast, Texas faced a shortfall of $18 billion for the coming two-year budget period, yet legislators and the governor declined to utilize any of the state’s $6 billion in reserves. Instead, the state imposed very deep cuts to preschools, K-12 schools, universities, health care, and other services, some of which are described below. Texas also used a gimmick – deliberately underfunding its Medicaid program – to close its budget. When the state legislature meets again in 2013, it likely will face a sizeable shortfall in funding for Medicaid, and will need either to find new revenues (perhaps by drawing on the state’s sizeable reserves at that time) or to impose additional deep spending cuts.Image

| Table 1: Seven States with Shortfalls Had Large “Rainy Day” Funds Available | ||

| State | 2012 Shortfall as Percent of FY11 Budget | 2011 Rainy Day Funds as a Percent of FY11 Budget |

| Iowa | 2.4% | 8.3% |

| Louisiana | 19.4% | 8.3% |

| Nebraska | 4.8% | 9.3% |

| New Mexico | 8.3% | 5.2% |

| South Carolina | 11.5% | 5.2% |

| South Dakota | 11.0% | 9.3% |

| Texas | 20.5% | 6.3% |

| Source: CBPP for shortfalls, NASBO for rainy day funds. Excludes Alaska, Delaware, North Dakota, West Virginia, and Wyoming which also had substantial reserves but did not project shortfalls for 2012. | ||

- A few states have raised new revenues. Since the recession began, more than 30 states have enacted revenue measures — in some cases significant ones — to replace some of the revenue lost due to the recession. (All of those have also cut services, often sharply.) For next year, of the 47 states that have enacted budgets, five states include major new revenue measures as well as spending cuts.[9] Their revenue proposals include:

- Connecticut’s enacted budget raises $2.6 billion in new tax revenue over the biennium by increasing the number of income tax brackets and other income tax changes, expanding the sales tax to cover more services and increasing the sales tax rate, and imposing a higher surcharge on corporations, among other increases.

- Hawaii raised over $600 million in new tax revenue over the biennium by limiting general excise tax exemptions for businesses and by eliminating the standard deduction and capping itemized deductions for higher income filers, among other actions.

- Maryland’s budget raised $85 million from an increase in the alcohol tax, and $64 million in increased motor vehicle fees.

- Nevada’s budget extended $620 million in tax measures that were scheduled to expire this year, including keeping the sales tax rate at 6.85 percent until July 2013. Previously the sales tax rate had been scheduled to drop to 6.5 percent this year. The budget also extended a payroll tax on businesses until 2013 and kept a business license fee, scheduled to drop to $100 this year, at $200 until July 2013.

- Prior to enacting the budget, Illinois lawmakers raised the state’s personal income tax to 5 percent from 3 percent and corporate income tax to 7 percent from 4.8 percent in order to help address the state’s budget shortfalls in 2011 and 2012. These measures are estimated to raise about $7 billion a year.

All of these governors are also cutting services, some deeply. But by raising new revenue, their proposals reduce the spending cuts needed to close the shortfalls. This balanced approach limits the harmful impact of budget shortfalls on the economy.

- Some states have enacted tax cuts, forcing even deeper cuts to services. For the first time since the recession caused state revenues to plummet, lawmakers in some states have enacted large tax cuts – mostly cuts to taxes paid by corporations and other businesses – in a misguided attempt to spur economic activity. Twelve states that faced FY12 budget shortfalls have enacted major tax cuts that would reduce revenues in the coming fiscal year.[10] (As described later in this paper, each of these states also enacted major spending cuts.) Some of these states, as well as several others such as California, Maryland, and New York also allowed major tax measures to expire or phase out, losing significant revenue and causing further cuts in spending.

- Arizona enacted a tax package that reduces the corporate income tax rate to 4.9 percent from 6.98 percent and reduces commercial property taxes by 10 percent. The package was signed into law on February 17 and will cost the state $38 million in fiscal year 2012, or 4 percent of the state’s 2012 budget shortfall. By fiscal year 2018, the cost of the tax cuts will balloon to $538 million, half of which will result from the corporate tax rate cut.

- Florida’s budget increases the amount of business income exempt from the corporate income tax to $25,000 from $5,000, resulting in the exemption of 15,000 businesses from the tax, at a cost to the state of $12 million in fiscal year 2012 and $29 million each year thereafter. The budget also imposes a cap on property tax collection by the state’s five water management districts, costing local districts $210 million.

- Georgia’s budget enacts nearly $100 million in tax cuts, including $46 million to allow top income earners unlimited itemized deductions on their income taxes.

- Maine’s budget eliminates in 2012 the state’s alternative minimum income tax on individuals, lowers in 2013 the state’s top income tax rate on income above about $50,000 to 7.95 percent from 8.5 percent, and doubles from $1 million to $2 million the income exempted from the state’s estate tax. To partially offset the costs of these tax cuts, the budget reduces by 20 percent targeted property tax assistance for middle and low-income homeowners and renters. These cuts will cost the state $130 million in the coming two-year budget cycle and $400 million in the following two-year cycle.

- Michigan eliminated the state’s current major business tax and replaced it with a flat 6 percent corporate income tax, exempting all but subchapter C corporations from paying a business income tax, at a cost of more than $1 billion in 2012 alone. To offset the revenue lost from reduced business taxes, the state will maintain and then phase down a temporary increase in the personal income tax, reduce the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit for low-income working families by 70 percent, and tax some pension income. The change also eliminates most business tax credits. The net result of these changes will be a revenue loss of $535 million for fiscal year 2012.

- Missouri eliminated its corporate franchise tax, which will cost the state $25 million in 2012 and $87million or about one-quarter of corporate tax receipts, when fully phased in.

- New Jersey’s budget includes a variety of tax cuts to begin in 2012. Among the tax cuts are a 25 percent reduction in the corporate minimum tax paid by the state’s subchapter S corporations; an increase in the amount of research a corporation can write off; consolidation and carry forward of certain business-related losses; and a modification of the corporate business tax formula used to determine the portion of a corporation’s income that is taxable in New Jersey. The cost of these tax cuts increases to $271 million in three years from an initial loss of $107 million in the first year.

- North Carolina let expire a temporary 1-cent sales tax increase, an income tax surcharge on higher income families and individuals, and an income tax surcharge on corporations, at a cost of $1.3 billion. The budget also enacts a two-year provision allowing business owners to exempt the first $50,000 in “pass-through” income from state income tax, so long as the business owner is actively engaged in running the business. For individual business owners with at least $50,000 in eligible business income, the value of the exemption would range from $3,000 to $3,875. The exemption will apply to the 2012 and 2013 calendar years and cost $132 million in the 2012 fiscal year and more than $300 million when in full effect.

- Ohio is eliminating its estate tax in 2013. The tax affected the wealthiest 7 percent of estates, and brought in approximately $286 million last year, 80 percent of which went straight to local governments to fund basic services like police, fire protection, and snow removal.

- In Wisconsin, lawmakers enacted over $90 million in new tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy. For example, corporations will be allowed to claim as a tax deduction a greater share of the losses they have incurred in past years and will tax less of their capital gains income. Together with other tax cuts enacted earlier this year, the total revenue loss to the state is about $200 million over the next two year budget cycle, requiring further budget cuts. Lawmakers filled $56 million of the budget shortfall by scaling back the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit for 152,000 low-income working families, at an average cost of $518 for families with 3 or more children and $154 for families with 2 children, annually.

Because states must balance their budgets, these tax cuts must be offset by increases in other taxes or additional service cuts. At best, the economy will lose as much as it gains. In practice, cutting corporate taxes likely will reduce in-state economic activity. That’s because some of the corporations’ tax savings would likely go to their out-of-state shareholders in the form of higher dividends — good for the shareholders but of no value to the state that cut the taxes. Moreover, if spending cuts reduce the quality of the state’s human capital and physical infrastructure—its schools, universities, transportation systems, and courts, for example —businesses will be less likely to invest in the state in the future.

Spending Cuts Will Weaken Schools, Reduce Access to Medical Care, and Cost Jobs

Since states spend more of their budgets on education and health care than anything else, lawmakers imposing large spending cuts are hard-pressed to avoid cutting back on these essential public services. Many states also will lay off state employees or cut their pay and benefits. These actions, coming on top of deep cuts that states have already made over the last three years, place a drag on the nation’s economic recovery.

Elementary and Secondary Education

At least 23 states have made identifiable cuts in support for public schools. In many cases, these cuts undermine school finance systems that are intended to reduce disparities between high-wealth and low-wealth school districts, so the largest impacts may be felt in communities that are least able to compensate for the loss of funds from their own resources.

- Arizona is cutting $183 million from K-12 education spending in the coming year and continues another $377 million in cuts that were implemented over the previous three years, bringing the total cut relative to pre-recession levels to $560 million, or $530 per pupil.

- Colorado is cutting state spending on K-12 education by $347 per pupil compared to last school year.

- Florida is cutting spending on K-12 education by $542 per pupil compared with last year. The state also has cut $13 million from the state’s school readiness program that gives low-income families access to high quality early care for their children. The cut means over 15,000 children currently participating in the program will no longer be served. Florida also reduced by 7 percent the per-student allocation to providers participating in the state’s universal prekindergarten program for 4-year-olds, which will mean that classrooms have more children per teacher.

- Georgia cut state and lottery funds for pre-kindergarten by 15 percent, which will mean shortening the pre-K school year from 180 to 160 days for 86,000 four-year-olds, increasing class sizes from 20 to 22 students per teacher, and reducing teacher salaries by 10 percent.

- Iowa reduced state funding for its statewide pre-kindergarten program for four-year-olds by 9 percent from last year. Schools serving these children will now receive fewer dollars per child and may have to make up for lost funds with reduced enrollment or higher property taxes. The state is also cutting back support for a community-based early childhood program that provides resources to parents with children from birth to age 5, including a cut of nearly 30 percent to preschool tuition assistance.

- Illinois is cutting general state aid for public schools by $152 million, on top of a loss of $415 million in expired federal recovery dollars — a total decrease of 11 percent. The budget takes $17 million from the state fund that supports early childhood education efforts, which may result in an estimated 4,000 fewer children receiving preschool services and 1,000 fewer at-risk infants and toddlers receiving developmental services. The budget also eliminates state funding for advanced placement courses in school districts with large concentrations of low-income students, mentoring programs for teachers and principals, and an initiative providing targeted, research-based instruction to students with learning difficulties.

- Kansas cut the basic funding formula for K-12 schools by $232 per-pupil, bringing this funding nearly 6 percent below fiscal year 2011 budgeted levels.

- For the third year in a row, Louisiana will fail to fund K-12 education at the minimum amount required to ensure adequate funding for at-risk and special needs students, as determined by the state’s education finance formula. Per student spending will be $215 below the level set out by the finance formula for FY12.

- Michigan is cutting K-12 education spending by $470 per student.

- Mississippi, for the fourth year in a row, will fail to meet the state’s statutory obligation to support K-12 schools, underfunding school districts by 10.5 percent or $236 million. The statutory school funding formula is designed to ensure adequate funding for lower-income and underperforming schools. According to the Mississippi Department of Education, the state’s failure to meet that requirement over the past three years has resulted in 2,060 school employee layoffs (704 teachers, 792 teacher assistants, 163 administrators, counselors, and librarians, and 401 bus drivers, custodians, and clerical personnel).[11]

- Missouri is freezing funding for K-12 education at last year’s levels. This means that for the second year in a row, the state has failed to meet the statutory funding formula established to ensure equitable distribution of state dollars to school districts.

- Nebraska altered its K-12 school aid funding formula to freeze state aid to schools in the coming year and allow very small increases thereafter, resulting in a cut of $410 million over two years.

- New Mexico cut K-12 spending by $42 million (1.7 percent). The governor is requiring school districts to spare “classroom spending” from the cuts, which means greater proportional cuts to other areas of K-12 education like school libraries and guidance counseling. The operating budget of the state education department is being cut by more than 25 percent.

- New York cut education aid by $1.3 billion, or 6.1 percent. This cut will delay implementation of a court order to provide additional education funding to under-resourced school districts for the third year in a row. Beyond cutting the level of education aid in FY12, the budget limits the rate at which education spending can grow in future years to the rate of growth in state personal income.

- North Carolina cut nearly half of a billion dollars from K-12 education in each year of the biennium compared to the amount necessary to provide the same level of K-12 education services in 2012 as in 2011. Both the state-funded prekindergarten program for at risk 4-year-olds and the state’s early childhood development network that works to improve the quality of early learning and child outcomes were cut by 20 percent. The budget also reduces by 80 percent funds for textbooks; reduces by 5 percent funds for support positions, like guidance counselors and social workers; reduces by 15 percent funds for non-instructional staff; and cuts by 16 percent salaries and benefits for superintendents, associate and assistant superintendents, finance officers, athletic trainers, and transportation directors, among others.

- Ohio is cutting state K-12 education funding 7.5 percent this year, a cut of $400 per student and equivalent to nearly 14,000 teachers’ salaries.

- Oklahoma is cutting funding for school districts by 4.5 percent, and makes additional cuts to the Department of Education’s budget. The Department of Education has voted to eliminate adult education programs, math labs in middle school, and stipends for certified teachers, among other things.

- Pennsylvania cut K-12 education aid by $422 million, or 7.3 percent, bringing funding down nearly to FY2009 levels. The budget also cuts $429 million dollars in additional funding that the state provides to school districts to implement effective educational practices (such as high quality pre-kindergarten programs) and maintain tutoring programs, among other purposes. Overall state funding for school districts was cut by $851 million or 13.5 percent, a cut of $485 per student.

- South Dakota cut K-12 education by 6.4 percent, next year, an amount equal to $416 per student, and 8.8 percent in 2013.

- Texas eliminated state funding for pre-K programs that serve around 100,000 mostly at-risk children, or more than 40 percent of the state’s pre-kindergarten students. The budget also reduces state K-12 funding to 9.4 percent below the minimum amount required by the state law. Texas already has below-average K-12 education funding compared to other states, and this cut would depress that low level even further at a time when the state’s school enrollment is growing. This would likely force school districts to lay off large numbers of teachers, increase class sizes, eliminate sports programs and other extracurricular activities, and take other measures that undermine the quality of education.

- Utah cut K-12 education by 5 percent, or $303, per pupil from the prior year’s levels.

- Washington is taking over $1 billion from state K-12 education funds designed to reduce class size, extend learning time, and provide professional development for teachers — a cut equal to $1,100 per student.

- Wisconsin reduced state aid designed to equalize funding across school districts by $740 million over the coming two-year budget cycle, a cut of 8 percent. The budget also reduces K-12 funds for services for at-risk children, school nursing, and alternative education.

Higher Education

At least 25 states have made large, identifiable cuts in funding for state colleges and universities, with direct impacts on students.

- Arizona cut funding for public universities by nearly one-quarter, or $200 million. This would add to deep previous cuts: from 2008 through 2011, state support for universities fell by $230 million, resulting in the elimination of more than 2,100 positions (an 11 percent reduction in the workforce). Universities have raised tuition significantly, closed eight extended campuses, and merged, consolidated, or disestablished 182 colleges, schools, programs, and departments. Combined with those previous cuts, the FY12 reduction brings per-student state funding down to 50 percent below pre-recession levels.[12]

Arizona also cut community college funding for operating expenses by about $73 million. The cut amounts to 6.2 percent of total community college operating revenues and half of all state support for community colleges. - California is increasing fees at community colleges starting this fall by 38 percent; for the average student, this means an annual fee increase of $300. The state also is reducing funding for the University of California (UC) and the California State University (CSU) systems by $1.3 billion ($650 million each). Since FY2008 California has cut funding for the UC system by 27 percent and has cut funding for the CSU system by almost 28 percent. In response to cuts in funding, the CSU will increase annual tuition by 29 percent, or $1,242 for full time undergraduate students (relative to the tuition rate that was in place at the beginning of last school year). UC will increase annual tuition by 18 percent, or over $1,800 for resident undergraduate students. UC tuition has grown by more than 80 percent since the 2007-08 academic year.

- Colorado cut state university spending by 11.5 percent over the prior year, which is expected to be offset with tuition increases of 9 percent, on average. The budget also cuts a means-tested stipend program for undergraduate students by 21 percent from what was budgeted for the current year.

- Florida cut state higher education spending and raised state university tuition for undergraduates by 8 percent. State universities are increasing tuition by another 7 percent to offset cuts in funding. This comes on the heels of tuition hikes equaling over 30 percent since the 2009-10 school year. The state has also cut a university merit-based scholarship program by 20 percent.

- Georgia cut funding for a popular merit-based college scholarship program serving hundreds of thousands of students by about one-fifth, university funding by 10 percent, and funding for technical colleges by 4 percent.

- Iowa is cutting state funding for public universities by $20 million, or around 4 percent. This brings state support below fiscal year 2007 levels.

- Louisiana enacted a 10 percent tuition increase for the state university system, or an average increase of around $600 more per year per student, in order to make up for the loss of federal and state dollars. Technical colleges will raise tuition by an average of $700 for full-time students.

- Massachusetts cut funding for higher education by $64 million, or 6.3 percent. Since FY2009, after adjusting for inflation, the state has cut funding by $185 million, or 16.3 percent.

- Michigan cut by 15 percent state support for public universities, and will increase the cut to about 20 percent for universities that raise tuition by more than 7 percent. Universities are already announcing tuition increases just under that limit, amounting to $600 - $900 tuition increases for in-state undergraduate students. The state also cut funding for community colleges by 4 percent.

- Minnesota is cutting state funding for higher education 12 percent below 2011 levels. This includes a $194 million cut to the University of Minnesota system and a $170 million cut to the Minnesota State Colleges and Universities system.

- Missouri cut state support for higher education by 7 percent. The cuts continue a trend of declining state support for Missouri’s universities and community colleges; over the last decade, state support for universities has fallen by 28 percent per student and support for community colleges has fallen by 12 percent.

- Nevada reduced state funding for the higher education system by 15 percent, which will result in an increase in undergraduate tuition of 13 percent in FY12 and an increase in graduate school tuition of 5 percent in FY12 and again in FY13.

- New Hampshire cut support for the university system almost in half in a single year, from $100 million to $52 million. University officials have announced that they will raise tuition 8.7 - 9.7 percent, eliminate around 200 positions, reduce employee benefits, dip into reserves, and take other measures as a result. Community colleges also face a 37 percent cut and will raise tuition 6.5 percent for the coming year, which will cost full time students up to $360 per year.

- New Mexico reduced by 8 percent state funding for public universities, which will result in a 5.5 percent tuition increase ($304 per student).

- New York cut state funding for the State University of New York (SUNY) by 7.6 percent, and reduces state funding for the City University of New York (CUNY) by 4.4 percent. To help them absorb the funding cuts, the legislature passed a bill that allows SUNY and CUNY to raise tuition by about 30 percent over the next five years. These tuition increases would affect 220,000 students in the SUNY system and 137,000 in the CUNY system and come on top of increases already imposed since the recession began. At SUNY, for example, substantial reductions in state support resulted in a 14 percent tuition increase in 2009.

- North Carolina cut nearly half of a billion dollars from higher education in each year of the biennium compared to the amount necessary to provide the same level of higher education services in 2012 as in 2011. The cuts mean that full-time resident community college students could see their tuition increase to $2,128 in FY12 and $2,208 in FY13 from the current $1,808 per year. Funds for community college basic education courses were cut by 12 percent.

North Carolina is also forcing the university system to find more than $330 million in savings in each year of the biennium. The state also is reducing by 59 percent (or $26 million each year) the state subsidy to university hospitals to offset the costs of uncompensated care, which the hospital system estimates at $300 million this year. - Oklahoma is cutting state funding for higher education by nearly 6.7 percent. Partially as a result, tuition and fees were increased by an average of 5.9 percent, or about $225 per student. The budget also cuts a career and technical education training program by about 6.5 percent.

- Ohio cut higher education funding 10 percent for FY12, amounting to $590 per student. Students at public universities face a 7 percent tuition increase as well as an undetermined (and uncapped) amount of fee increases.

- Pennsylvania cut funding for the state’s system of higher education by $91 million, or 18 percent. The budget also cuts funding for the state’s four “state related” universities (Penn State, the University of Pittsburgh, Temple, and Lincoln University) by roughly 20 percent. As a result, the University of Pittsburgh will increase in-state tuition by 8.5 percent and Temple University will increase in-state tuition by almost ten percent. Other state universities will see tuition increases of 7.5 percent.

- South Dakota cut higher education (and most other agencies) by 10 percent. The Board of Regents voted to raise tuition by 6.9 percent, or $490 per student, on average. The tuition increase covers only part of the loss of state funding, and each university has to determine how it will make up for the remaining loss of funds.

- Tennessee cut funds for the University of Tennessee system by 25 percent compared to 2011. Tuition within the system will rise 6 to 10 percent.

- Texas reduced general revenue spending on higher education by 9 percent over two years. This includes a cut of 5 percent to college and university formula spending, a cut of 10 percent in formula spending for health institutions, such as nursing schools, and a cut of 25 percent to funds for university research centers, graduate programs, and other non-operations spending. Enrollment growth is not funded for any higher education institution. The budget also cuts by 10 percent financial aid awards under the Texas grant program, which combines state and institutional money to cover tuition and fees for public school students with financial need and good academic records. The cut will likely result in smaller awards.

- Utah is cutting its higher education budget by about 1 percent below last year’s level, bringing the total decline in state spending to 2 percent since 2009. These funding cuts come despite rapidly rising enrollment. For example, enrollment in Utah’s system of higher education in the spring 2011 semester was 4 percent above enrollment the previous year. The failure of state funding to keep up with enrollment growth will result in an average tuition increase of 7.5 percent.

- Washington is cutting state funding for colleges and universities by more than $500 million and raising tuition in the upcoming school year by anywhere from 11 percent to 16 percent compared with last year.

- Wisconsin is cutting $250 million from the state university system, with nearly $100 million of that cut coming from funds for UW-Madison. The budget freezes financial aid at current levels despite expected tuition increases of 5.5 percent system-wide and a recently approved tuition increase of 8.3 percent for UW-Madison, creating an even larger funding gap that students and their families will have to fill. The budget also cuts state support for technical colleges by about $70 million over the biennium, or 25 percent, and places a two-year freeze on local property tax levies that allow communities to raise funds for technical colleges.

Health Care

At least 20 states have made deep, identifiable cuts in health care that will reduce access to care for low-income children, seniors, families and people with disabilities.

- Alabama ’s funding for Medicaid will be $57 million short of the amount needed to maintain existing services. As a result, the state’s Medicaid agency is considering reducing access to prescription drugs, kidney dialysis, and transplants, among other services.

- Arizona plans to eliminate Medicaid coverage for 100,000 adults who otherwise would qualify by freezing new enrollment, and it creates new eligibility rules for the remaining 150,000 childless participants in the program that include new co-payments and a requirement that they re-qualify for coverage every six months (rather than annually); the budget also eliminates coverage for about 30,000 poor parents, imposes a 5 percent cut in Medicaid provider rates that would take effect in April 2011, and gives the Governor the discretion to impose new or increase copayments and fees, and to limit access to the program.

Arizona’s budget also continues a freeze on KidsCare (SCHIP) that began in January 2010. Since that time, about 60,000 children who would be eligible for the program have applied but not received coverage. - California is cutting state funding for Medi-Cal (the state’s Medicaid program) by over $1.6 billion. The state will impose co-pays on Medicaid recipients ranging from $3 for generic prescriptions to $100 per day for hospital stays, cut provider payments by 10 percent, and limit doctor’s visits for MediCal patients to 7 per year unless they are deemed medically necessary by a physician, among other measures. The state will also scale back its Healthy Families (CHIP) program by almost doubling premiums for families with incomes between 151 and 250 percent of poverty (a change affecting an estimated 565,000 children), and increasing co-payments, among other cuts.

- Colorado reduced funds for various medical, dental, and long-term care services for poor adults and children. Among other things, the cuts will result in limits on physical and occupational therapy visits and on routine dental visits, and lower provider rates, which now have been reduced by more than 6 percent since the start of the recession.

- Florida reduced Medicaid payment rates by 12 percent for most hospitals, by 6.5 percent for nursing homes, and by 4 percent for centers that provide medical care to people with developmental disabilities.

- Idaho is making $35 million in cuts to Medicaid. Due to the reduction, over 42,000 people will lose access to preventative dental care, 6,500 adults (those without chronic conditions) will lose all optometry, vision, and podiatry benefits, and nearly 3,000 adults with a serious mental illness will face a reduction in the number of hours of rehabilitation services they may receive.

- Maine eliminated Medicaid eligibility for legal immigrants who have been in the country for fewer than five years, with the exception of children and pregnant women. Under this change, roughly 1,300 to 1,400 adult immigrants will lose access to coverage.

- Maryland is cutting Medicaid payments to hospitals by $250 million, which will be made up for by a 2.5 percent assessment on hospitals. Hospitals are allowed to pass 85 percent of that cost onto insurance companies and patients through a 2.5 percent increase in fees.

- Massachusetts is cutting funding for MassHealth (the state’s Medicaid program) by $750 million below the amount needed to maintain the program in its current form. The state expects to achieve these savings in substantial part through reduced payments to providers.

- Nebraska is cutting by 2.5 percent the rates at which it reimburses providers for care under both the Medicaid program (for non-primary care) and the state’s health care program for children.

- New Hampshire cut the state’s uncompensated care fund – which helps support many small rural hospitals that are often their regions’ only source of health care and a major regional employer – by more than 75 percent. Hospitals will charge higher rates to patients with private insurance to make up for this cut.

- New Jersey is making steep cuts to Medicaid eligibility that will require federal approval. Under the new plan, income eligibility for a family of three would drop to $5,300 from around $25,000. If approved, an estimated 23,000 parents who otherwise would have been eligible will lose health coverage. The budget also increases Medicaid co-payments for adult day care provided outside of the home.

- New York is cutting total Medicaid spending from all sources by $337 million, or 1 percent, relative to 2011 levels.

- North Carolina is cutting Medicaid provider rates at least 2 percent and requiring additional cuts compared to the amount necessary to provide the same level of health services in 2012 as in 2011.

- Rhode Island is shifting health care costs to families. An estimated 10,000 families and an additional 6,000 children will have their monthly premiums go up by $30 to $36.

- South Carolina is cutting Medicaid provider rates by 2 percent to 7 percent, and increasing the cost of each doctor’s office visit, home health visit, clinic visit, and optometrist visit by $1.

- South Dakota cut Medicaid funding by 6.6 percent. This includes an average provider rate cut of 7 percent, which may cause some doctors to stop taking new patients or to drop existing patients.

- Texas is cutting Medicaid hospital provider rates by 8 percent, making it more difficult for Texas doctors to accept Medicaid patients because of the state’s already-low reimbursement levels relative to private insurance and Medicare. The state also plans to reduce spending by over $800 million over the next two years by reducing the health services for which low-income adults (other than seniors) are eligible under Medicaid. Even once those cuts are implemented, the amount budgeted for Medicaid is not expected to fund the program over the entire two-year budget period, which will mean legislators will have to reconvene to fill that gap later on.

- Washington has frozen enrollment for the state's Basic Health Plan serving approximately 40,000 low-income residents, which is expected to reduce the number of participants to 37,000 in 2012 and to 33,000 in 2013. The budget also reduces by an average of 10 percent in-home personal care hours for 45,000 seniors and persons with disabilities needing in-home care.

- Wisconsin granted the state Department of Human Services the authority to make about $200 million in unspecified cuts to Medicaid services. The state plans to request a federal waiver to change eligibility rules, increase copayments and cost-share rules, and reduce benefits. If the waiver is not granted, the state will lower the income eligibility ceiling to 133 percent of the poverty level from 200 percent for parents and childless adults, which would eliminate coverage for about 70,000 people.

Other Services

- Arizona is cutting back the state’s lifetime eligibility limit for cash and other assistance to the poor to two years from its current limit of three years, immediately ending benefits for 3,500 low-income families. It also eliminates state funding that subsidizes child care for low-income families, denying 13,000 children assistance.

- California is cutting CalWORKs (TANF) grants. For instance, the maximum monthly CalWORKs grant for a family of three in high-cost counties will drop from $694 to $638, an 8 percent cut. The state also reduced the lifetime limit on the number of months that a needy adult can receive CalWORKs cash assistance from 60 to 48 months. The budget also cut funding for services that counties provide to help parents transition from welfare to work, such as job training, job search assistance, and subsidized child care, by $369 million.

California also cut Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP) grants for individuals to the minimum allowed by federal law. These grants provide cash assistance to low-income elderly and disabled residents to help them meet their basic needs. This cut drops the maximum SSI/SSP grant for individuals to $830, down 8.5 percent from the $907 maximum grant provided in January 2009. - Georgia is eliminating state funds for a subsidized employment program. The state also won’t replace expired Recovery Act dollars that helped to fund child care subsidies, which is expected to result in 9,600 fewer children receiving assistance.

- Illinois is making a number of cuts in human services programs. It is cutting funding for state-operated developmental disability and mental health centers by 14 percent below 2011 levels and is cutting preventative mental health services, including early intervention and treatment services for children, by 20 percent below 2011 levels. The state also is cutting funding for TANF income assistance by one-third and eliminating cash support to 9,000 adults who cannot work and are ineligible for other cash benefits. Funding for a program that provides emergency and transitional housing to more than 40,000 people each year is being cut in half. Funding for an after-school program that serves more than 20,000 at-risk youth, was reduced 42 percent.

- Louisiana is reducing by more than 30 percent state support for child and family services, including disaster preparedness, services for neglected and abused children and victims of domestic violence, and child care assistance. If the cut were applied to child care alone, it would mean that the number of low-income children whose parents receive child care subsidies would decrease by 10,000. The state budget also cuts funding for youth services by 12 percent, which will mean elimination of alternative schooling for 900 at-risk youth and a reduction in the length of treatment programs for troubled teens to 30-45 days from six to nine months.

- Maine is denying temporary cash assistance and food stamps to poor families and individuals who have been in the country fewer than five years.

- Massachusetts is cutting funding for child care subsidies by $13.8 million or 3 percent. After adjusting for inflation, child care subsidies have been cut $65 million or 12.9 percent since 2009.

- Michigan is cutting by one-quarter monthly cash assistance to poor people with disabilities. The budget also eliminates 124,000 poor children from a program that helps with the purchase of school clothes and eliminates funding that helps poor families with funeral expenses.

- Nebraska is eliminating food assistance, health care, cash assistance, and aid to the elderly and disabled for anyone who has not been in the country for five years. The state also is canceling all non-education aid to cities and counties— a cut of $44 million over the biennium.

- New Jersey is cutting in half state funding for a program that provides medication to 7,700 moderate-income people with AIDS. In addition, the state will no longer provide funds to a non-profit providing afterschool programming to children across the state. The cut will immediately result in the loss of affordable afterschool programs for over 5,000 children and job loss for 500 afterschool educators.

- New Hampshire appropriated barely half the funds requested by the governor for substance abuse services. This will eliminate prevention services for about 12,000 people, most of them youth, and reduce services for another 800. Cuts to prevention and treatment are likely to increase strain on law enforcement and emergency room services.

- North Carolina is eliminating state funds that support county-level social service departments providing services like energy assistance, adult day care and disability services, child welfare, and child care assistance.

- Ohio is cutting funding for early care and education services provided to 100,000 children each month by 9 percent, in part by reducing the maximum income needed to be eligible for the program to 125 percent of the federal poverty line from 150 percent (in other words, to $22,000 from $26,000 for a family of three). Ohio also will cut aid to local governments by 13 percent in 2012 and another 40 percent in 2013, compared with 2011 levels. The state will reduce by $500 million over two years payments promised to localities as compensation for phasing out a property tax that provided local revenue.

- Oklahoma is increasing copayments for low-income parents receiving child care assistance by up to $60 per month, depending on family size and income, affecting 13,000 families. In addition, the maximum annual income for families to receive child care assistance has been lowered by $6,000, thereby reducing the number of families who can qualify.

- Oregon is no longer allowing poor parents receiving cash assistance through TANF to enter a program through which they can fulfill their work requirements through pursuit of a degree at a two- or four-year college.

- Pennsylvania is cutting funding for subsidized childcare by 10 percent, which will increase costs for families and reduce payments to child care providers.

- Rhode Island cut in half its spending on the state’s general assistance program, which provides $200 per month in cash assistance to nonelderly poor adults who are unable to work because of an illness, injury, or other medical condition that will last longer than 30 days. Because of the cut in funds, recipients will only receive the payment once every four months instead of once every month.

- Texas is cutting programs helping to prevent child abuse and neglect by nearly half.

- Washington eliminated a cash assistance program for most of the 28,000 poor individuals with disabilities currently receiving that assistance. The budget also cuts in half funding for state food assistance to 14,000 low-income, legal immigrants ineligible for federal food stamps, which will significantly reduce the benefits these people will receive.

- Wisconsin authorizes the state to reduce eligibility for state child care assistance, increases co-pays, begin waiting lists and decrease reimbursement rates. Those changes could supersede state statutes, without rulemaking or any legislative oversight. The budget also eliminates a state-funded program providing food assistance to legal immigrants in the country less than five years.

Job and Pay Cuts for Public Employees

At least 16 states have enacted layoffs or specific cuts in pay and/or benefits for state workers. These cuts are in addition to workforce cuts already implemented in 44 states since the recession began. Since August 2008, state and local governments have eliminated more than 577,000 jobs.

- Alabama increased public employee pension contributions by 50 percent (from 5 percent of salaries to 7.25 percent in 2012 and 7.5 percent in 2013). The state will also reduce its contribution to employee and teacher’s health insurance plans by 5 percent.

- Florida terminated employment for 1,300 public employees and eliminates another 3,100 positions. Public employees not currently making pension contributions will be required to contribute 3 percent of their salaries; in addition, the retirement age or years of service requirements will go up 3 to 5 years and the pension vesting period will increase by two years for new employees.

- In Kansas, state employees will pay a 2.5 percent surcharge on state employee health premiums in addition to what they already pay for the 2012 plan year.

- Louisiana eliminated 3,450 positions, which will result in an estimated 1,600 people being laid off. In addition, for the second year in a row Louisiana is suspending merit-based salary increases for state employees.

- Maine raised the retirement eligibility age for most new hires and employees with less than five years of service to 65 from 62, and freezes the cost of living adjustment for pension benefits for three years. After that point, the adjustment will only be applied to the first $20,000 in benefits.

- In Maryland, public employees will contribute 7 percent of their salaries to pensions, up from 5 percent, and will face an increase in the combined “age plus years of service” requirement for full retirement benefits. Cost of living adjustments will be limited to 1 percent in years when pension fund investments yield under 7.75 percent. If the investments yield at least that amount, COLAs can reach up to 2.5 percent. In addition, in the following fiscal year, employees’ share of health insurance premiums also will rise to 25 percent from 20 percent.

- Nebraska offered no pay raises for state employees in FY2012. For some state employees this will be the second year in a row with no pay raise.

- In Nevada, public employees will have their pay reduced by 2.5 percent and be subject to six unpaid furlough days or another 2.3 percent salary decrease. In addition, K-12 teachers and administrators are subject to a 2.5 percent salary decrease (to be negotiated with local school districts) plus a 5 percent salary contribution to the pension system, above current contributions.

- Budget cuts in New Hampshire have already resulted in 130 public sector layoffs, with many more likely to occur. An earlier version of the budget that cut $280 million less from spending anticipated 255 layoffs.

- New Jersey is shifting costs to public employees by increasing the amount public employees contribute to their retirement, eliminating automatic cost-of-living increases for retirees, raising retirement ages and increasing health insurance contributions.

- New Mexico extended a temporary pension contribution requirement of 1.5 percent of salaries for public employees earning over $20,000, and increases the contribution by 1.75 percentage points to 3.25 percent.

- New York assumed $450 million in “workforce” savings, which could mean as many as 9,800 layoffs if an agreement is not reached with public employees. Recently the state reached tentative agreements with its two largest employee unions. If ratified by the unions’ memberships, the agreements would freeze union members’ salaries for three years and require union members to pay a greater share of their health insurance costs and take five unpaid furlough days this year.

- The cuts in state support for public education in Texas could force school districts to lay off as many as 49,000 teachers and other education workers.

- In Vermont, public employee salary contributions to the retirement plan are increasing to 6.4 percent from 5.1 percent. State workers’ wages are frozen following 3 to 5 percent wage cuts in January.

- Teachers in Washington are taking a 1.9 percent pay cut. Other school employees and all other state workers earning more than $2,500 per month are taking 3 percent salary cuts. Washington is also eliminating automatic cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) to public employee pensions.

- Wisconsin is making sweeping changes to state employee policies and pay. The state is requiring that state workers make 6 percent salary contributions to their pensions and pay, on average, $576 more per year for a single health insurance premium or $1,428 more for the family plan.

End Notes

[*] Kwame Boadi, Dylan Grundman, Andrew Hartsig, Phil Oliff, Ashali Singham, and Katherine Sydor gathered much of the information necessary to write this report.

[1] This count includes four states where the budget processes are nearly complete. In Iowa, Governor Branstad is expected to sign the budget by the end of July. In Oregon, the budget has been enacted but Governor Kitzhaber has not yet fully completed the veto process. New Jersey’s Governor vetoed pieces of the budget passed by the legislature, but may revise some of the cuts in funding made by those vetoes. Connecticut enacted a budget that hinged upon negotiations with public sector unions, but those negotiations fell through, leaving the state with a $1.6 billion gap to address; Governor Malloy has put forth a plan to close this gap through layoffs and cuts to Medicaid and a range of other state programs, but it appears that the state might ultimately reach an agreement with the public employee unions, thereby making many of these cuts unnecessary. This count excludes three states – Kentucky, Virginia, and Wyoming – that are in the middle of a two-year budget cycle and will not be enacting new budgets for the 2012 fiscal year.

[2] This figure refers to spending proposed in states’ operating budgets – typically referred to as general fund spending. While there is some variation by state, general fund spending is usually funded with general revenues collected by the state, such as income and sales taxes. Massachusetts is a clear exception: there, the operating budget includes federal funds and spending of non-general state funds. For the sake of comparison with other states in this paper, we have netted out federal funds from Massachusetts’s spending figures. Also, to be consistent with previous years, California’s general fund spending total for FY2012 includes $7.7 billion associated with the realignment of certain services to local governments.

[3] Many of the cuts that have already been implemented are described in a separate Center on Budget and Policy Priorities publication, “An Update on State Budget Cuts.” It is not always possible to identify specific cuts in an enacted budget, largely because many states do not provide enough information in budget documents to determine whether a cut is being imposed or not. For example, many states do not indicate what the cost would be to maintain the same level of services as the previous year, so it may not be possible to say whether the appropriation is enough to maintain services or whether instead it will require that cuts be made.

[4] This figure refers to revenues projected to be available for states’ operating budgets -- typically referred to as general fund revenues. While there is some variation by state, general fund revenues are typically revenues collected by the state, such as income and sales taxes. As with the spending figures in this paper, there are a couple of exceptions. In Connecticut and Massachusetts, operating revenues include federal funds and non-general state revenue. For the sake of comparison with other states in this paper, we have netted out federal funds from Massachusetts’s revenue figures and all identifiable federal funds from Connecticut’s revenue figures. Also, to be consistent with previous years, California’s general fund revenue total for FY2012 includes $5.1 billion associated with the realignment of certain services to local governments.

[5] U.S. Department of Education, Condition of Education 2011, tables A-2-1, A-8-1, and A-9-1.

[6] CBPP calculations based on data from the Congressional Budget Office and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

[7] The Senate rejected this proposal on March 9, 2011. James R. Horney, “House GOP Proposal Means Fewer Children in Head Start, Less Help for Students to Attend College, Less Job Training, and Less Funding for Clean Water,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated March 1, 2011.

[8] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “An Update on State Budget Cuts.”

[9] Some states have enacted tax measures that will raise smaller amounts of money. Examples include California and Texas, which enacted laws aimed at requiring Internet sellers such as Amazon to collect sales and use taxes. Rhode Island expanded its sales tax base and will implement a minimum filing fee for LLCs, LLPs, and LPs.

[10] Three other states -- Idaho, Iowa, and New Hampshire – that faced budget shortfalls are also cutting taxes, but on a much smaller scale. Iowa expanded a business tax credit that will balloon in cost from $300,000 in FY12 to $7.7 million in FY14; the legislature also enacted a measure that would divert up to $60 million in better-than-expected revenues each year into a fund to be used at the Governor’s discretion. Idaho enacted a business tax credit that will cost $7.9 million per year and New Hampshire will become the first state in 50 years to decrease its tobacco-related taxes, which will cost the state $14 million over the two-year budget period. New Hampshire also eliminated its tax on gambling winnings. Two other states, Delaware and North Dakota, also cut taxes but were not facing budget shortfalls.

[11] Job loss figures from oral testimony given by the state superintendent to the Joint Budget Legislative Committee at a public hearing on September 21, 2010 and communicated to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities by the Mississippi Economic Policy Center.

[12] Arizona Board of Regents, “Statement by Arizona Board of Regents Chairman Anne Mariucci on Passage of FY2012 State Budget,” April 1, 2011, http://azregents.asu.edu/palac/newsreleases/Anne%20Mariucci%20Statement%20on%20Passage%20of%20FY12%20State%20Budget.pdf

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Areas of Expertise